Artists Are a Tool for Gentrification’: Maintaining Artists and Creative Production in Arts Districts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Profile for the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Theatre

Khamar Hopkins Sunday, February 24, 2019 AAD 612 - Marketing and the Arts Michael Crowley Community Profile for The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Theatre The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Theatre, or better known as the Parkway, is a historic theatre located in the heart of Baltimore’s Station North Arts and Entertainment District that recently reopened its doors in the spring of 2017. The Parkway first opened its doors on October 23rd, 1915, with the feature premiere of Zaza, directed by Hugh Ford and Edwin S. Porter, and starring Pauline Fredrick.i During its first decade the Parkway would screen Paramount movies, had an orchestra, an organ, a cameraman, and could seat up to 1100 patrons. In 1926 the theatre was purchased and remodeled by Loews Incorporated, also known as Loew’s Cineplex Entertainment Corporation (as of January 26, 2006, Loews was acquired by AMC Entertainment Inc.)ii and 2 years later it got rid of its orchestra for Vitaphone and Movietone sound systems, and could now only seat 950 customers. The theatre would continue to function as a Loews theatre until it closed during the summer of 1952. With its next owner, Morris Mechanic, the Parkway had a short-lived season as a live theatre before it closed again. On May 24th, 1956, the Parkway reopened under the new name, 5 West, with the premiere of Ladykillers, and started rebranding itself as an art-house cinema. The new 5 West cinema could only hold 435 guests and provided great entertainment to the local community along with its neighboring theatres, but it started to struggle in the late 1970’s and then closed its doors again in the winter of 1978. -

SG the Fitzgerald Brochure New.Indd

FOR LEASE Maryland DC • Virginia Online 605 South Eden Street, Ste 200 1600 Wilson Boulevard, Ste 930 www.segallgroup.com Baltimore, MD 21231 Arlington, VA 22209 Member of 410.753.3000 202.833.3830 Where the Midtown neighborhoods of Mt Vernon, Station North and Bolton The Opportunity Hill meet, you will fi nd The Fitzgerald. Inspired by F. Scott Fitzgerald and Approximately 19,000 square feet of prime space is available on the energy of his era, this Baltimore development offers more than just two levels – 14,359 on the ground fl oor and 5,069 square feet on a somewhere to hang your hat. The developer, Bozzuto Group, blended Mezzanine level open to the fl oor below. These two areas are currently connected by elevator and escalator and, due to Oliver Street’s rising stunning features with fantastic amenities in a culturally rich environment. slope, both at street grade. Entertainment, grocery or fi tness uses are Sandwiched between the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) and the sought for the larger portion or the entirety, while the smaller area can University of Baltimore, The Fitzgerald is a mixed use project consisting of be demised for a café that caters to this culturally rich party of the City. almost 25,000 square feet of dynamic urban retail space, 275 residential units and a 1,250 space parking garage that serves University of Baltimore Quick Facts students as well as area visitors. The project’s retail component is ideal for LLocationocation Retail space in Luxury Apartment Building entertainment, service, retail and restaurant uses to serve students and faculty, 19,428 square feet SSizeize neighborhood residents, out of town visitors, local offi ce workers and patrons (14,359 lower level and 5,069 Mezzanine) of the great local entertainment and cultural venues including the Lyric Opera DDeliveryelivery Immediate House & Theater, The Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, and the Parkway, Centre and RRentalental RRateate Negotiable Charles Theatres in the nearby “Station North” Arts District. -

Front and Center: a 5-Year Equity Plan for Central Baltimore

AUGUST 2017 A 5-year Equity Plan for Central Baltimore TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary Chapter 1: Introduction A. Purpose of Plan B. Central Baltimore Partnership C. Homewood Community Partners Initiative D. Progress To Date E. Why a New Plan F. Making Equity Front and Center G. Planning Process: 1. Front and Center Plan Goal 2. Phase 1: Understanding Existing Conditions 3. Phase 2: Preliminary Recommendations 4. Phase 3: Finalizing the Front and Center Plan Chapter 2: Planning Context H. Central Baltimore History I. Existing Conditions Chapter 3: Recommendations and Implementation Plan J. Recommendations • Social Fabric: Youth and Families • Economic Mobility: Workforce Development and Opportunities • Community Health: Physical and Mental Health, Safety, Public Space • Housing Access: Preserving Affordability, Improving Quality, Expanding Choices 2 CREDITS Planning Team: Keswick Multi-Care Center Joe McNeely, Planning Consultant Lovely Lane United Methodist Church Neighborhood Design Center, Design Consultant Maryland Bay Construction Maryland New Directions Planning Partners: Mosaic Community Services, Inc. 29th Street Community Center Open Works AHC, Inc. Greater Baltimore - Workforce Program People’s Homesteading Group Annie E. Casey Foundation Strong City Baltimore Association of Baltimore Area Grantmakers Telesis Baltimore Corporation (ABAG) Wells Fargo Regional Foundation Baltimore City Department of Housing and Community Development Data Work Group Members: Baltimore City Department of Planning Assistant Commissioner, Maryland -

Charm of the Baltimore Region HOST COMMITTEE’S GUIDE

DISCOVER THE Charm of the Baltimore Region HOST COMMITTEE’S GUIDE The Maryland City/County Management Association and ICMA’s 2018 Conference Host Committee are excited to welcome you to Baltimore for ICMA’s 104th Annual Conference. From the bustling Inner Harbor, where the Baltimore Convention Center is located, to the city’s many historical sites, renowned museums, inspiring architecture, and diverse neighborhoods, Baltimore has something for everyone. So get out and discover the many reasons why Baltimore is known as Charm City! wrote some of the early stories that would make him the father of the modern short story, creating and Historical Sites defining the modern genres of mystery, horror, and History abounds in Baltimore. A must-see stop while science fiction. you’re in town is Fort McHenry. During the War of 1812, Westminster Hall is a beautiful building troops at Fort McHenry stopped a British advance into located at the intersection of Fayette and the city, inspiring Francis Scott Key to pen our national Greene Streets in downtown Baltimore. anthem. Administered by the National Park Service since This restored historic church features 1933, Fort McHenry is the only area of the National Park stained glass windows, an 1882 pipe System to be designated as both a national monument organ, cathedral ceilings, and raised and a historic shrine. balconies. The Westminster Burying History enthusiasts may also want to visit the Star-Spangled Grounds, one of Baltimore’s Banner Flag House, Mary Pickersgill’s 1793 home where oldest cemeteries, features the she made the 30-by-42-foot flag that flew over Fort gravesite of Edgar Allan Poe. -

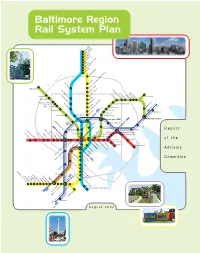

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

Maryland Film Festival Director of Development the Maryland Film Festival (Mdff) Seeks a Seasoned Director of Development To

Maryland Film Festival Director of Development The Maryland Film Festival (MdFF) seeks a seasoned Director of Development to create and implement the fund development strategy and plans to maximize contributed revenue from individuals, corporations, foundations and government sources. The mission of the Maryland Film Festival (MdFF) is to bring films, filmmakers, and audiences together in a friendly, inclusive atmosphere that reflects the unique aspects of our community, while participating in and adding to the larger film dialogue across the country and across the world. Film for Everyone. In the fall of 2018 MdFF adopted a five-year plan to fully realize its role in Baltimore and the field as a respite for filmmakers, a world-class destination for cinema, and a stalwart advocate for the democratizing the power of story, as told through film, and expressed through each individual storyteller’s voice. The SNF Parkway functions as a multi-disciplinary film, community, and education hub serving a broad cross- section of the Baltimore public and beyond. MdFF leverages the powerful assets of the Johns Hopkins University, Maryland Institute College of Art and surrounding campus communities to function as a vibrant, regional nerve center for dialogue, discussion, and debate on the key issues of the day, with film as the central axis in broad public discussions. Through programming, education and community ventures, MdFF is establishing a year-round a platform for all voices that are reflective of the diverse population of greater Baltimore and the nation. The five-year strategic plan has recently been extended through 2025 with a revised model season to account for online screenings, hybrid programming, and the return of in-person movie-watching at the SNF Parkway. -

The Guy's Guide to Baltimore

The Guy's Guide to Baltimore 101 Ways To Be A True Baltimorean! By Christina Breda Antoniades. Edited by Ken Iglehart. Let’s assume, for argument’s sake, that you’ve mastered the Baltimore lexicon. You know that “far trucks” put out “fars” and that a “bulled aig” is something you eat. You know the best places to park for O’s games, where the speed traps are on I-83, and which streets have synchronized traffic lights. You know how to shell a steamed crab. You never, EVER attempt to go downy ocean on a Friday evening in the dead of summer. And, let’s face it, you get a little upset when your friends from D.C. call you a Baltimoro… well, you know. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Do you really know all it takes to be a true Baltimorean? ¶ Here, we’ve compiled a list of the 101 activities, quirky habits, and oddball pastimes, that, even if you only did half of them, would earn you certification as a true Baltimorean. Some have stood the test of time, some are new favorites, but all are unique to Charm City. If you’re a grizzled native, you’ll probably find our list a fun test that takes you down memory lane. And if you’re new in town, the guide below will definitely help you to pass yourself off as a local. ¶ So, whether you’ve been here 60 days or 60 years, we’re sure you’ll find something new (or long forgotten) in the pages that follow. -

B E C K E R B R O T H E

11 E. Mt. Royal Ave and 7 E. Preston St, Baltimore, MD 21201 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SALE OPPORTUNITY 11 E. MT. ROYAL AVE AND 7 E. PRESTON ST BALTIMORE, MD 21201 36,500+/- GROSS SQUARE FOOT RECENTLY REDEVELOPED OFFICE AND RETAIL BUILDING WITH ELEVATOR AND 37 PARKING SPACES BYRNES & ASSOCIATES, INC. 11 E. Mt. Royal Ave and 7 E. Preston St, Baltimore, MD 21201 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY: Built in 1920, 11 E Mount Royal Avenue previously served as a Zell Motor Car Company showroom and dealership. Today, the building is being Redeveloped and is offering ground level Retail units, traditional Office suites, 22 Coworking office suites, and a Penthouse office suite with a rooftop deck that offers sweeping city views. Modern renovations will showcase the elegant historic features of this downtown Baltimore landmark. 11 E Mount Royal is located on the bustling Mount Royal Ave just minutes from Penn Station, The University of Baltimore and across the street from The John and Frances Angelos Law Center. The building is situated in the Mt. Vernon Cultural District, a neighborhood widely considered as the Cultural and Arts epicenter in Baltimore City. Mt. Vernon is one of Baltimore's oldest and well-preserved neighborhoods and is designated as a National Historic Landmark District. Major employers in the neighborhood include: Chase Brexton Health Services, the University of Baltimore, and Agora Inc. Mt. Vernon’s central location in Baltimore City, as well as accessibility to public transportation and main city thoroughfares, makes it easily accessible to Downtown Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University, Johns Hopkins Hospital, and the suburbs of Baltimore City. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216 -

Space and Governance in the Baltimore DIY Punk Scene: An

Wesleyan University The Honors College Space and Governance in the Baltimore DIY Punk Scene An Exploration of the postindustrial imagination and the persistence of whiteness as property by Mariama Eversley Class of 2014 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Anthropology Middletown, Connecticut April, 2014 Table of Contents Images of Baltimore 3 Introduction 5 I: COMMON SENSE, CITIZENSHIP, AND HORIZONTALISM 16 A) DIY ethics and Common Sense 30 B) Insurgent Citizenship and Grassroots Space making 46 C) Horizontalism: Leaderlessness and Empowerment 67 D) Conclusion to Chapter I 83 II: BALTIMORE AS THE SETTING OF THE PUNK SCENE 87 A) Social History and Cheap Space 91 B) The effects of Neoliberalism in Baltimore 108 C) Whiteness as Property 115 D) Conclusion to Chapter II 133 III: CONCLUSION 136 2 1: Olson, Sherry H. Baltimore, The Building of an American City. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP 1980: 59 3 2: Olson, Sherry H. Baltimore, The Building of an American City. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1980: 398 3: Olson, Sherry H. Baltimore, The Building of an American City: Johns Hopkins UP, 1980: xvi 4 Introduction The first Do-it-yourself (DIY) music show I ever went to was in my senior year of high school. I went with two other friends from my private high school in Baltimore County to see two local bands; a punk set from Dope Body and a hip-hop duo called The Rap Dragons. We drove from my friend’s white wealthy suburban enclave called Homeland toward east Baltimore, not too far from Johns Hopkins University. -

Second Place 2010 Abell Award in Urban Policy

Second Place 2010 Abell Award in Urban Policy MARYLAND ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICTS: A PROCESS EVALUATION AND CASE STUDY OF BALTIMORE Cailin McGough Paul Messino Johns Hopkins University Institute for Policy Studies Masters in Public Policy Program The Abell Award in Urban Policy is presented annually to the student who writes the most compelling paper on a pressing problem facing the City of Baltimore and feasible strategies for addressing it. This award is co-sponsored by The Abell Foundation and the Johns Hopkins Institute for Policy Studies. Acknowledgments This research grew from the prior analysis we conducted as part of the 2008 Fall Baltimore Policy Project at John Hopkins University’s Institute for Policy Studies. We gathered subsequent interviews, observation and research for this paper through May 2010. We would like to thank Dr. Sandra Newman for the impetus to investigate the revitalization taking place in Station North and for her continued support. In addition, Dr. Curtis Ventriss provided insight that guided our research and Bonnie Wittstadt of John Hopkins University’s Milton S. Eisenhower Library aided us in the creation of A&E district maps. We would also like to thank David Bielenberg of Station North Arts and Entertainment Inc., Chris Ryer and Hillary Chester of Southeast Community Development Corporation, and all of the artists, residents, business owners and other stakeholders in Baltimore’s A&E districts who contributed to this report. Pamela Dunne of the Maryland State Arts Council and Jesse Rye of the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies provided valuable background information. We want to emphasize that this analysis is not meant to evaluate the program's impact or assess district "success." Rather, our scope is limited to the design of tax credits and the extent to which they are being used, with findings based on available data and interviews focusing on Baltimore's districts. -

About Baltimore—Charm City

Baltimore, Maryland - Charm City, USA Baltimore is the principal city and port of entry of Maryland and is the 13th largest city in the US, with a metropolitan area population in excess of 2.5 million. More than 100,000 students live in the Baltimore metropolitan area. Baltimore was named for the first Lord Baltimore, George Calvert, who was granted a charter key by King Charles in 1632 to establish an English colony in the New World. The first settlement on the site was made in 1662, and the town of Baltimore was laid out in 1730. The city owes its existence to the natural, deep- water harbor formed where the Patapsco River empties into the mammoth Chesapeake Bay. From its 1730 founding to the present, Baltimore has been a vital shipbuilding center and one of the nation’s largest commercial ports. Baltimore is centrally located and is only 40 miles away from Washington D.C., 70 miles away from Philadelphia, and is about 180 miles away from the New York City. By Maryland’s MARC train it costs about $5 and takes less than an hour to reach Washington, D.C. and by Amtrak train it costs about $60 and takes about 2.5 hours to Reach New York City. You can also reach New York by Greyhound bus for $25-35 (about 4-hour trip). Baltimore–Washington International Airport is one of the biggest and busiest airports in the nation and is a hub for US Airways, Southwest and United Airlines. One can catch a direct flight from Baltimore to almost any major city in America.