Baltimore Chapter of Lambda Alpha International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neighborhood Series NW: Park Heights

Neighborhood Series NW: Park Heights thank you for joining us Speakers Martha Nathanson Yolanda Jiggetts Kelly Baccala VP for Government Relations & Executive Director, Neighborhood Development Officer, Community Development, City of Baltimore LifeBridge Health, Inc. Park Heights Renaissance Farmer Chippy Dana Henson Urban Farmer Vice President, Plantation Park Heights Urban Farm The Henson Development Company. Inc. Moderator Bryce Turner President, BCT Design Group Park Heights CREW Baltimore Neighborhood SeriesPark –HeightsNorth February 17, 2021 Commercial Strategy Park Heights CREW Baltimore Neighborhood Series – North February 17, 2021 Overall Neighborhood Image Park Heights CREW Baltimore Neighborhood SeriesPark –HeightsNorth February 17, 2021 Concept Plan Park Heights CREW Baltimore Neighborhood Series – North February 17, 2021 Park Heights CREW Baltimore Neighborhood SeriesPark –HeightsNorth February 17, 2021 Short-Term Recommendations (12 to 18 months) Park Heights CREW Baltimore Neighborhood SeriesPark –HeightsNorth February 17, 2021 Short-Term Recommendations (12 to 18 months) Park Heights CREW Baltimore Neighborhood Series – North February 17, 2021 Concept Plan Park Heights CREW Baltimore Neighborhood Series – North February 17, 2021 Concept Plan Park Heights CREW Baltimore Neighborhood Series – North February 17, 2021 Speaker Yolanda Jiggetts Executive Director, Park Heights Renaissance Park Heights: A Community of Great People and Great Assets Yolanda Jiggetts Executive Director Park Heights Renaissance, Inc. Park Heights -

Community Profile for the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Theatre

Khamar Hopkins Sunday, February 24, 2019 AAD 612 - Marketing and the Arts Michael Crowley Community Profile for The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Theatre The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Theatre, or better known as the Parkway, is a historic theatre located in the heart of Baltimore’s Station North Arts and Entertainment District that recently reopened its doors in the spring of 2017. The Parkway first opened its doors on October 23rd, 1915, with the feature premiere of Zaza, directed by Hugh Ford and Edwin S. Porter, and starring Pauline Fredrick.i During its first decade the Parkway would screen Paramount movies, had an orchestra, an organ, a cameraman, and could seat up to 1100 patrons. In 1926 the theatre was purchased and remodeled by Loews Incorporated, also known as Loew’s Cineplex Entertainment Corporation (as of January 26, 2006, Loews was acquired by AMC Entertainment Inc.)ii and 2 years later it got rid of its orchestra for Vitaphone and Movietone sound systems, and could now only seat 950 customers. The theatre would continue to function as a Loews theatre until it closed during the summer of 1952. With its next owner, Morris Mechanic, the Parkway had a short-lived season as a live theatre before it closed again. On May 24th, 1956, the Parkway reopened under the new name, 5 West, with the premiere of Ladykillers, and started rebranding itself as an art-house cinema. The new 5 West cinema could only hold 435 guests and provided great entertainment to the local community along with its neighboring theatres, but it started to struggle in the late 1970’s and then closed its doors again in the winter of 1978. -

Alliance for Historic Landscape Preservation 35 Annual Meeting

Alliance for Historic Landscape Preservation 35th Annual Meeting Abstracts of Papers, Works-In-Progress, and Posters Resilience, Renewal, and Renaissance: Keeping Cultural Landscapes Relevant Lynchburg, Virginia March 20–23, 2013 The Question of Relevance: Ideas from Italo Calvino Ian Firth, Professor Emeritus, University of Georgia, Athens In May 1999, Lynn Beebe, Poplar Forest's first president, challenged a group of professionals and academics involved in preservation to come up with ideas that would go beyond a conventional museum approach for this preservation project and give it additional relevance. At that time, acquisition of the surrounding landscape was still a major hurdle though restoration of Jefferson's house was well underway, so responses to Beebe's challenge focused on the use of the house. Now, in 2013, with work on the curtilage underway, the best way to treat and use the wider agricultural landscape of Jefferson's plantation remains the subject of debate. This situation is not unusual at many historic places. It can be attributed to various factors including the complex ecological and social problems that have to be addressed in large-scale landscape preservation projects, while the substantial costs of initial work and long-term maintenance inevitably raise questions about the relevance of such ambitious undertakings. Several authorities in the field of historic preservation including Kevin Lynch and David Lowenthal have addressed the issue of relevance and their ideas have been widely circulated. This presentation considers questions raised by someone less well known in this field, Italo Calvino. In his book 'Invisible Cities', Calvino presents a wide variety of ideas, many in the form of questions and caveats concerning attitudes towards our environment and our past. -

Entire Public Libraries Directory In

October 2021 Directory Local Touch Global Reach https://directory.sailor.lib.md.us/pdf/ Maryland Public Library Directory Table of Contents Allegany County Library System........................................................................................................................1/105 Anne Arundel County Public Library................................................................................................................5/105 Baltimore County Public Library.....................................................................................................................11/105 Calvert Library...................................................................................................................................................17/105 Caroline County Public Library.......................................................................................................................21/105 Carroll County Public Library.........................................................................................................................23/105 Cecil County Public Library.............................................................................................................................27/105 Charles County Public Library.........................................................................................................................31/105 Dorchester County Public Library...................................................................................................................35/105 Eastern -

Green V. Garrett: How the Economic Boom of Professional Sports Helped to Create, and Destroy, Baltimore's

Green v. Garrett: How the Economic Boom of Professional Sports Helped to Create, and Destroy, Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium 1953 Renovation and upper deck construction of Memorial Stadium1 Jordan Vardon J.D. Candidate, May 2011 University of Maryland School of Law Legal History Seminar: Building Baltimore 1 Kneische. Stadium Baltimore. 1953. Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore. Courtesy of Enoch Pratt Free Library, Maryland’s State Library Resource Center, Baltimore, Maryland. Table of Contents I. Introduction........................................................................................................3 II. Historical Background: A Brief History of the Location of Memorial Stadium..............................................................................................................6 A. Ednor Gardens.............................................................................................8 B. Venable Park..............................................................................................10 C. Mount Royal Reservoir..............................................................................12 III. Venable Stadium..............................................................................................16 A. Financial History of Venable Stadium.......................................................19 IV. Baseball in Baltimore.......................................................................................24 V. The Case – Not a Temporary Arrangement.....................................................26 -

All Hazards Plan for Baltimore City

All-Hazards Plan for Baltimore City: A Master Plan to Mitigate Natural Hazards Prepared for the City of Baltimore by the City of Baltimore Department of Planning Adopted by the Baltimore City Planning Commission April 20, 2006 v.3 Otis Rolley, III Mayor Martin Director O’Malley Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction .........................................................................................................1 Plan Contents....................................................................................................................1 About the City of Baltimore ...............................................................................................3 Chapter Two: Natural Hazards in Baltimore City .....................................................................5 Flood Hazard Profile .........................................................................................................7 Hurricane Hazard Profile.................................................................................................11 Severe Thunderstorm Hazard Profile..............................................................................14 Winter Storm Hazard Profile ...........................................................................................17 Extreme Heat Hazard Profile ..........................................................................................19 Drought Hazard Profile....................................................................................................20 Earthquake and Land Movement -

MJC Media Guide

2021 MEDIA GUIDE 2021 PIMLICO/LAUREL MEDIA GUIDE Table of Contents Staff Directory & Bios . 2-4 Maryland Jockey Club History . 5-22 2020 In Review . 23-27 Trainers . 28-54 Jockeys . 55-74 Graded Stakes Races . 75-92 Maryland Million . 91-92 Credits Racing Dates Editor LAUREL PARK . January 1 - March 21 David Joseph LAUREL PARK . April 8 - May 2 Phil Janack PIMLICO . May 6 - May 31 LAUREL PARK . .. June 4 - August 22 Contributors Clayton Beck LAUREL PARK . .. September 10 - December 31 Photographs Jim McCue Special Events Jim Duley BLACK-EYED SUSAN DAY . Friday, May 14, 2021 Matt Ryb PREAKNESS DAY . Saturday, May 15, 2021 (Cover photo) MARYLAND MILLION DAY . Saturday, October 23, 2021 Racing dates are subject to change . Media Relations Contacts 301-725-0400 Statistics and charts provided by Equibase and The Daily David Joseph, x5461 Racing Form . Copyright © 2017 Vice President of Communications/Media reproduced with permission of copyright owners . Dave Rodman, Track Announcer x5530 Keith Feustle, Handicapper x5541 Jim McCue, Track Photographer x5529 Mission Statement The Maryland Jockey Club is dedicated to presenting the great sport of Thoroughbred racing as the centerpiece of a high-quality entertainment experience providing fun and excitement in an inviting and friendly atmosphere for people of all ages . 1 THE MARYLAND JOCKEY CLUB Laurel Racing Assoc. Inc. • P.O. Box 130 •Laurel, Maryland 20725 301-725-0400 • www.laurelpark.com EXECUTIVE OFFICIALS STATE OF MARYLAND Sal Sinatra President and General Manager Lawrence J. Hogan, Jr., Governor Douglas J. Illig Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Tim Luzius Senior Vice President and Assistant General Manager Boyd K. -

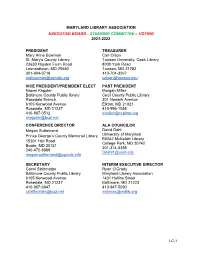

MLA Organizational Structure

MARYLAND LIBRARY ASSOCIATION EXECUTIVE BOARD - STEERING COMMITTEE – VOTING 2021-2022 PRESIDENT TREASURER Mary Anne Bowman Carl Olson St. Mary’s County Library Towson University, Cook Library 23630 Hayden Farm Road 8000 York Road Leonardtown, MD 20650 Towson, MD 21252 301-904-0718 410 - 704 - 3267 [email protected] [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT/PRESIDENT ELECT PAST PRESIDENT Naomi Keppler Morgan Miller Baltimore County Public library Cecil County Public Library Rosedale Branch 301 Newark Avenue 6105 Kenwood Avenue Elkton, MD 21921 Rosedale, MD 21237 410 - 996 - 1055 410-887-0512 [email protected] [email protected] CONFERENCE DIRECTOR ALA COUNCILOR Megan Sutherland David Dahl Prince George’s County Memorial Library University of Maryland B0242 McKeldin Library 15301 Hall Road College Park, MD 20742 Bowie, MD 20721 301-314-0395 240-472-8889 [email protected] [email protected] SECRETARY INTERIM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Conni Strittmatter Ryan O’Grady Baltimore County Public Library M ary land Library Association 6105 Kenwood Avenue 1401 Hollins Street Rosedale, MD 21237 Baltimore, MD 21223 410-887-6047 410 - 947 - 5090 [email protected] [email protected] I-C-1 EXECUTIVE BOARD – APPOINTED OFFICERS - VOTING 2021-2022 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT LEGISLATIVE Tyler Wolfe Andrea Berstler Baltimore County Public Library Carroll County Public Library 3202 Bayonne Avenue 1100 Green Valley Road Baltimore, MD 21214 New Windsor, MD 21776 410-905-6866 443-293-3136 cell: 443-487-1716 [email protected] [email protected] INTELLECTUAL FREEDOM Andrea -

Baltlink Rider Guide-944004A2.Pdf

WHAT IS BALTIMORELINK? BaltimoreLink is a complete overhaul and rebranding of the core transit system operating within Baltimore City and the surrounding region. Many of MTA’s current bus routes are outdated, and BaltimoreLink will improve service through a more reliable and efficient network. BaltimoreLink also includes transfer facilities, dedicated bus lanes, signal priority, and improved bus stop signs, among many other improvements. To deliver an interconnected transit network, existing MTA bus and rail services will be restructured and renamed: • CityLink: Twelve new high-frequency, color-coded bus routes will connect with each other, as well as Metro SubwayLink, Light RailLink, MARC Train, Commuter Bus, Amtrak, and other services, into one integrated transit network. • LocalLink (currently Local Bus): LocalLink routes will provide comprehensive crosstown connections and improved connections to neighborhoods and communities throughout the system. • Express BusLink (currently Express Bus): Express BusLink will include several existing Express Bus services that provide suburb-to- city connections and recently launched routes providing suburb-to-suburb connections. Typically, Express Bus routes have fewer stops and use higher speed roads. • Light RailLink (currently Light Rail): Light Rail service will operate along the same line but with improved connections to buses. • Metro SubwayLink (currently Metro Subway): This service will not change but will have improved connections to buses. baltimorelink.com | 1 BETTER BUS STOPS BALTIMORELINK RESOURCE INFORMATION To create a better rider experience by providing information you can use, the MTA will be All MTA routes will change under installing new bus stop signs throughout the BaltimoreLink. Please look for Rider Alerts for entire MTA bus network. -

Port Services Guide for Visiting Ships to Baltimore

PORT SERVICES GUIDE Port Services Guide For Visiting Ships to Baltimore Created by Sail Baltimore Page 1 of 17 PORT SERVICES GUIDE IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS IN BALTIMORE POLICE, FIRE & MEDICAL EMERGENCIES 911 Police, Fire & Medical Non-Emergencies 311 Baltimore City Police Information 410-396-2525 Inner Harbor Police (non-emergency) 410-396-2149 Southeast District - Fells Point (non-emergency) 410-396-2422 Sgt. Kenneth Williams Marine Police 410-396-2325/2326 Jeffrey Taylor, [email protected] 410-421-3575 Scuba dive team (for security purposes) 443-938-3122 Sgt. Kurt Roepke 410-365-4366 Baltimore City Dockmaster – Bijan Davis 410-396-3174 (Inner Harbor & Fells Point) VHF Ch. 68 US Navy Operational Support Center - Fort McHenry 410-752-4561 Commander John B. Downes 410-779-6880 (ofc) 443-253-5092 (cell) Ship Liaison Alana Pomilia 410-779-6877 (ofc) US Coast Guard Sector Baltimore - Port Captain 410-576-2564 Captain Lonnie Harrison - Sector Commander Commander Bright – Vessel Movement 410-576-2619 Search & Rescue Emergency 1-800-418-7314 General Information 410-789-1600 Maryland Port Administration, Terminal Operations 410-633-1077 Maryland Natural Resources Police 410-260-8888 Customs & Border Protection 410-962-2329 410-962-8138 Immigration 410-962-8158 Sail Baltimore 410-522-7300 Laura Stevenson, Executive Director 443-721-0595 (cell) Michael McGeady, President 410-942-2752 (cell) Nan Nawrocki, Vice President 410-458-7489 (cell) Carolyn Brownley, Event Assistant 410-842-7319 (cell) Page 2 of 17 PORT SERVICES GUIDE PHONE -

Artists Are a Tool for Gentrification’: Maintaining Artists and Creative Production in Arts Districts

International Journal of Cultural Policy ISSN: 1028-6632 (Print) 1477-2833 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gcul20 ‘Artists are a tool for gentrification’: maintaining artists and creative production in arts districts Meghan Ashlin Rich To cite this article: Meghan Ashlin Rich (2017): ‘Artists are a tool for gentrification’: maintaining artists and creative production in arts districts, International Journal of Cultural Policy, DOI: 10.1080/10286632.2017.1372754 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2017.1372754 Published online: 06 Sep 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 263 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gcul20 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CULTURAL POLICY, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2017.1372754 ‘Artists are a tool for gentrification’: maintaining artists and creative production in arts districts Meghan Ashlin Rich Department of Sociology/Criminal Justice, University of Scranton, Scranton, PA, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This study investigates the relationship between arts-themed development Received 7 June 2017 and the strategies used by neighborhood stakeholders, including artists Accepted 16 August 2017 and other marginalized populations, to maintain their place in gentrifying KEYWORDS arts and cultural districts. Using a case study of a state-sanctioned Arts & Artist communities; creative Entertainment District in Baltimore, MD (U.S.A.), I find that the organizations placemaking; gentrification; that are ‘thoughtful’ in their development actively seek to maintain the urban planning and policy production of arts and the residency of artists in the neighborhood into perpetuity. -

COVID-19 FOOD INSECURITY RESPONSE GROCERY and PRODUCE BOX DISTRIBUTION SUMMARY April – June, 2020 Prepared by the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative

COVID-19 FOOD INSECURITY RESPONSE GROCERY AND PRODUCE BOX DISTRIBUTION SUMMARY April – June, 2020 Prepared by the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative OVERVIEW In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative developed an Emergency Food Strategy. An Emergency Food Planning team, comprised of City agencies and critical nonprofit partners, convened to guide the City’s food insecurity response. The strategy includes distributing meals, distributing food, increasing federal nutrition benefits, supporting community partners, and building local food system resilience. Since COVID-19 reached Baltimore, public-private partnerships have been mobilized; State funding has been leveraged; over 3.5 million meals have been provided to Baltimore youth, families, and older adults; and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Online Purchasing Pilot has launched. This document provides a summary of distribution of food boxes (grocery and produce boxes) from April to June, 2020, and reviews the next steps of the food distribution response. GOAL STATEMENT In response to COVID-19 and its impact on health, economic, and environmental disparities, the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative has grounded its short- and long-term strategies in the following goals: • Minimizing food insecurity due to job loss, decreased food access, and transportation gaps during the pandemic. • Creating a flexible grocery distribution system that can adapt to fluctuating numbers of cases, rates of infection, and specific demographics impacted by COVID-19 cases. • Building an equitable and resilient infrastructure to address the long-term consequences of the pandemic and its impact on food security and food justice. RISING FOOD INSECURITY DUE TO COVID-19 • FOOD INSECURITY: It is estimated that one in four city residents are experiencing food insecurity as a consequence of COVID-191.