The Grimm Tales in 19Th Century Denmark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The New Look” in the History of Linguistics (1965)

“The New Look” in the History of Linguistics (1965) W. Keith Percival What follows here is a summary of a paper presented at the 128th Meeting of the Lin- guistic Circle of Madison on December 9, 1965. A complete typescript or manuscript has not survived. Fortunately, Jon Erickson, the recorder of the Linguistic Circle of Madison, entered this detailed digest of the paper into the Linguistic Circle’s minutes. At the request of Charles T. Scott, the secretary of the Madison Linguistics department graciously provided me with copies of the minutes referring to all the papers that I presented to the Linguistic Circle in the years 1965- 69 while I was teaching linguistics at the Milwaukee campus of the University of Wisconsin. Needless to say, I feel much indebted to Professors Scott and Erickson, and to the departmental secretary. ---------- The purpose of “‘The New Look’ in the History of Linguistics” was to review two stan- dard treatises on the history of linguistics, namely Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft in Deutschland by Theodor Benfey (1869), and Linguistic Science in the Nineteenth Century by Holger Pedersen (1931) . In spite of the way Theodor Benfey (1809–1881) implicitly outlined the subject matter of his book in the title [“History of Linguistics and Oriental Philology since the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, with a Retrospective Glance at Earlier Periods”], he in fact devoted much attention to linguistic studies spanning the entire period from the end of the medieval period to the beginning of the nineteenth century. In his so-called retrospective survey [Rückblick auf die früheren Zeiten ], he dealt with the Renaissance and the eighteenth century in remarkable detail. -

The Manuscript Collection of Rasmus Christian Rask

Tabularia Sources écrites des mondes normands médiévaux Autour des sagas : manuscrits, transmission et écriture de l’histoire | 2016 The library of the genius: The manuscript collection of Rasmus Christian Rask La bibliothèque d’un génie : la collection de manuscrits de Rasmus Christian Rask La Biblioteca di un genio: la collezione di manoscritti di Rasmus Christian Rask Silvia Hufnagel Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tabularia/2666 DOI: 10.4000/tabularia.2666 ISSN: 1630-7364 Publisher: CRAHAM - Centre Michel de Boüard, Presses universitaires de Caen Electronic reference Silvia Hufnagel, « The library of the genius: The manuscript collection of Rasmus Christian Rask », Tabularia [Online], Autour des sagas : manuscrits, transmission et écriture de l’histoire, Online since 17 November 2016, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tabularia/2666 ; DOI : 10.4000/tabularia.2666 CRAHAM - Centre Michel de Boüard h e library of the genius: h e manuscript collection of Rasmus Christian Rask La bibliothèque d’un génie: la collection de manuscrits de Rasmus Christian Rask La Biblioteca di un genio: la collezione di manoscritti di Rasmus Christian Rask Silvia Hufnagel Austrian Academy of Sciences, Institute for Medieval Research [email protected] Abstract: h e Arnamagnæan Institute at the University of Copenhagen houses the Old Norse- Icelandic manuscript collection of the famous Danish linguist Rasmus Rask (1787-1832) that comprises 127 post-medieval volumes. h e topics covered in the manuscripts rel ect Rask’s widespread interests and range from literature to non-i ctional works, such as linguistics, history, law and liturgy. It seems that Rask’s large network of friends and acquaintances was of help in his ef orts of acquiring manuscripts. -

Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege's 1993 Translation Of

Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege’s 1993 Translation of Rasmus Rask’s Prize Essay of 1818 Frans Gregersen To cite this version: Frans Gregersen. Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege’s 1993 Translation of Rasmus Rask’s Prize Essay of 1818. 2013. hprints-00786171 HAL Id: hprints-00786171 https://hal-hprints.archives-ouvertes.fr/hprints-00786171 Preprint submitted on 7 Feb 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege’s 1993 Translation of Rasmus Rask’s Prize Essay of 1818* 1. Introduction This edition constitutes a photographic reprint of the English edition of Rasmus Rask‘s prize essay of 1818 which appeared as volume XXVI in the Travaux du Cercle Linguistique de Copenhague in 1993. The only difference, besides the new front matter, is the present introduction, which serves to introduce the author Rasmus Rask, the man and his career, and to contextualize his famous work. It also serves to introduce the translation and the translator, Niels Ege (1927–2003). The prize essay was published in Danish in 1818. In contrast to other works by Rask, notably his introduction to the study of Icelandic (on which, see further below), it was never reissued until Louis Hjelmslev (1899–1965) published a corrected version in Danish as part of his edition of Rask‘s selected works (Rask 1932). -

Denmark — Backgrounds

LIBER Manuscript Librarians Group Manuscript Librarians Group Denmark — Backgrounds Ivan Boserup (Royal Library, Copenhagen) Contents: Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen (collection history; major collections; catalogues and digitisation; other collections). — Statsbibliotekets Håndskriftsamling, Aarhus. — Danmarks Kunstbibliotek, Copenhagen. — Dansk Folkemindesamling, Copenhagen. — Den Arnamagnæanske Samling, Copenhagen. — Karen Brahes Bibliotek, Odense. — Statens Arkiver, Copenhagen. — Det Danske Udvandrerarkiv, Aalborg. — Arbejderbevægelsens Arkiv, Copenhagen. — Arktisk Instituts Arkiv, Copenhagen. — Kvindehistorisk Samling, Aarhus. — Niels Bohr Arkivet, Copenhagen. — Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen. — Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen. Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen (collection history) 1. The Royal Library was founded by King Frederik III (1609-1670) in the 1650s by merging his private library with that inherited from his predecessors, and in particular by acquiring four important private libraries, The Bibliotheca Regia in the Castle of Copenhagen in his time housed more than 100 manuscripts, and was confirmed as National Library in the Danish Legal Deposit Law of 1697. Booty of war and acquisitions of whole manuscript collections from private scholars and collectors characterise the early 18th century. The Great Fire of Copenhagen, which spared the Royal Library and the Royal Archives, but annihilated the University Library, marks an intensification of manuscript acquisitions both in the private and in the public sphere. Besides important Icelandic codices, all the Danish medieval sources collected over the years by successive specially appointed Royal Historiographers were destroyed. New manuscript collections were established for the University Library, largely through private donations, but daring auction purchases and acquisitions of whole manuscript collections were also made, both privately and by the state. 2. The Collectio Regia or Old Royal Collection of manuscripts had grown to ca. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Daňo Juraj - (2007) do výtvarného života vstúpil tesne po 2. svetovej vojne; v tvorbe prekonal niekoľko vývojových zmien, od kompozícií dôsledne a detailne interpretujúcich farebné a tvarové bohatstvo krajiny, cez krajinu s miernou farebnou, tvarovou i rukopisnou expresionistickou nadsádzkou, až ku kompozíciám redukujúcim tvary na ich geometrickú podstatu; tak v krajinárskych, ako aj vo figurálnych kompozíciách, vyskytujúcich sa v celku jeho tvorby len sporadicky, farebne dominuje modro – fialovo – zelený akord; po prekonaní experimentálneho obdobia, v ktorom dospel k výrazne abstrahovanej forme na hranici informačného prejavu, sa upriamoval na kompozície, v ktorých sa kombináciou techník usiloval o podanie spoločensky závažnej problematiky; vytvoril aj celý rad monumentálno-dekoratívnych kompozícií; od roku 1952 bol členom východoslovenského kultúrneho spolku Svojina, zároveň členom skupiny Roveň; v roku 1961 sa stal členom Zväzu slovenských výtvarných umelcov; od roku 1969 pôsobil ako umelec v slobodnom povolaní; v roku 1984 mu bol udelený titul zaslúžilého umelca J. Daňo: Horúca jeseň J. Daňo: Za Bardejovom Heslo DANO – DAR Strana 1 z 22 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia J. Daňo J. Daňo: Drevenica Heslo DANO – DAR Strana 2 z 22 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia J. Daňo: J. Daňo Heslo DANO – DAR Strana 3 z 22 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia J. Daňo: Ulička so sypancom J. Daňo: Krajina Daňový peniaz - Zaplatenie dane cisárovi dánska loď - herring-buss Dánsko - dánski ilustrátori detských kníh - pozri L. Moe https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Danish_children%27s_book_illustrators M Christel Marotta Louis Moe O Ib Spang Olsen dánski krajinári - Heslo DANO – DAR Strana 4 z 22 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Danish_landscape_painters dánski maliari - pozri C. -

RASMUS KRISTIAN RASK (1787-1832) LIV OG LEVNED Af Hans Frede Nielsen

RASMUS KRISTIAN RASK (1787-1832) LIV OG LEVNED af Hans Frede Nielsen I dette bidrag om Rasmus Rasks liv og levned1 vil jeg først sige noget om hans barndom og ungdom, derefter berette om hans store rejse til Sverige, Rusland, Persien og Indien i årene 1816-1823 og endelig skitsere hans levned og arbejde fra hjemkomsten i 1823 og indtil hans alt for tidlige død den 14. november 1832, altså for 175 år siden. I min afsluttende vurdering af Rasks videnskabelige virke vil jeg af pladsmæssige grunde begrænse mig til nogle enkelte forhold, der har haft min særlige bevågenhed, men som også skulle have almen interesse. Rasmus Rask (eller Rasmus Christian Nielsen Rasch, som hans døbenavn var) blev født den 22. november 1787 i beskedne kår i Brændekilde på Fyn. Han var søn af en husmand og skrædder, der tillige agerede 'klog' mand i lokalsamfundet, og som iøvrigt var ret belæst. Rasmus var fra barnsben af videbegærlig og fik sin læselyst vakt af faderens bøger og skrifter, ikke mindst af værker om historiske emner. Som tretten-årig kom han på den lærde skole i Odense, hvor han vakte en vis opsigt i kraft af sin påklædning og væsen. Hans skolekammerat Niels Matthias Petersen (1791-1862), der selv var fra Sanderum, og som iøvrigt blev den første professor i de nordiske sprog på Københavns Universitet i 1845, giver følgende beskrivelse af Rask i de tidlige skoledage (Petersen 1834:2): Rask kom i Odense Skole i April 1801. Hans lille Vækst, hans levende Öjne, den Lethed, hvormed han bevægede sig og sprang om over og på Borde og Bænke, hans usædvanlige Kundskaber, ja selv hans afstikkende Bondedragt vakte hans Meddisciples Opmærksomhed. -

THE BROTHERS GRIMM and HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN Cay

THE BROTHERS GRIMM AND HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN Cay Dollerup, Copenhagen, Denmark Abstract In broad terms the genre we usually term ‘fairytales’ first appeared in France, whose culture and language are central to in European history, when Charles Perrault published Les Contes de ma Mère l’Oye (or Contes) in 1697. The genre was invigorated in Germany, notaby by the Kinder- und Hausmärchen (1812) of the brothers Grimm. Both France and Germany were large nations and dominant in European cultural life, but small Denmark also stands out in the history of the Euro- pean fairytales in the 19th century. The reason is that the Dane Hans Christian Andersen wrote Eventyr (1835) that have also become well-known internationally. Andersen never credited the brothers Grimm as a source inspiration about his inspiration for writing fairytales. In this paper I shall discuss the history of the Grimm Tales, the Danish response to them, the way the German Tales were edited, the story of Andersen’s life and the reasons why he never credited the brothers Grimm for inspiring him to write fairytales. His narratives were not the creations of his fertile ima- gination only. But the story behind this, with the brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen as the towering figures, is complex. The brothers Grimm and Napoleonic Europe The brothers Grimm began collecting tales in the kingdom of Westphalia.1 Unlike today’s unified Germany, Napoleonic ‘Germany’ consisted of numerous more or less autonomous fiefs, principalities, and kingdoms. One of these was the landgravedom of Hesse with less than 10,000 square kilometres and half a milli- on inhabitants. -

The Roles of Rasmus Rask and Gustaf Renvall in the Publishing and Editing of Christfrid Ganander’S Nytt Finskt Lexicon

265 The roles of Rasmus Rask and Gustaf Renvall in the publishing and editing of Christfrid Ganander’s Nytt Finskt Lexicon Elina Palola & Petri Lauerma After his visit to Finland in 1818, Rasmus Rask organized the publication of Christfrid Ganander’s Nytt Finskt Lexicon (MS 1786–1787) with the finan- cial help of Russian patron Nikolay Rumyantsev. The dictionary was edited by Rask’s Finnish teacher Gustaf Renvall. This article shows that despite Renvall’s abridgements, the dictionary retains archaic expressions. 1. Rasmus Rask and Finland The famous Danish scholar Rasmus Rask (1787–1832) was one of the found- ers of comparative linguistics. His studies in Germanic and Nordic languages formed the basis for the understanding of sound correspondencies between re- lated languages. Rask also studied several other languages, among them Finn- ish and Lappish, finding them unrelated to Indo-European languages. Wanting more material for his comparisons he visited Finland as a part of the long trip that eventually led him through Russia to places as distant as Caucasus and Ceylon. (On Rasmus Rask e.g. Hovdhaugen, Karlsson, Henriksen & Sigurd 2000:159–164.) Rask came to Turku in March 1818. He was in Finland for only a month but managed to meet many eminent Finnish scholars and inspire them to study Finnish language and mythology. At first Rask started to take Finnish lessons from Gustaf Renvall (1781–1841), who at that time was adjunct (associate professor) of history and docent of Finnish language. Rask’s notes from these lessons formed the basis of his own unpublished Finnish grammar (Lauerma 2019). -

Networks and Faces Between Copenhagen and Canton, 1730-1840

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Asmussen, Benjamin Doctoral Thesis Networks and Faces between Copenhagen and Canton, 1730-1840 PhD Series, No. 23.2018 Provided in Cooperation with: Copenhagen Business School (CBS) Suggested Citation: Asmussen, Benjamin (2018) : Networks and Faces between Copenhagen and Canton, 1730-1840, PhD Series, No. 23.2018, ISBN 9788793579934, Copenhagen Business School (CBS), Frederiksberg, http://hdl.handle.net/10398/9639 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/209070 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons -

University of Copenhagen, Denmark

Language and Ideology in Denmark Gregersen, Frans Published in: Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe Publication date: 2011 Citation for published version (APA): Gregersen, F. (2011). Language and Ideology in Denmark. In T. Kristiansen, & N. Coupland (Eds.), Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe (1 ed., Vol. I, pp. 47-56). Novus forlag. Standard Language Ideology in Contemporary Europe Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 Language and ideology in Denmark Frans Gregersen University of Copenhagen, Denmark This chapter has three sections. The first section summarizes the historical and economic bases of the Danish speech community. The second summarizes what we know about linguis- tic developments since 1900, and the third attempts to connect this knowledge to the various ideological currents characteristic of the period. SOCIO-HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Denmark as a linguistically homogeneous nation state, 1864 as a crucial turning point Denmark arguably comes closest to realizing Ernest Renan’s wet dream of ‘one nation, one language’. This is a result of history. The once grand Danish realm was gradually reduced to only those provinces where Danish were spoken: Norway was lost to Sweden in 1814, and Iceland declared its independence in 1944. Most importantly, the (mostly) Low German- speaking provinces of Schleswig and Holstein were lost to Prussia in 1864. The loss of these rich provinces, in Danish history and contemporary ideology making up the southernmost part of Jutland, ‘Sønderjylland’, created a long-lasting trauma ostensibly threatening Denmark as an independent state – and crucially a Denmark which was geographically small and linguis- tically exceptionally homogeneous. This was indeed taken as the point of departure for the plebiscite which resulted in the ‘homecoming’ of a part of Slesvig in 1920 after Germany’s defeat in the First World War: Those parts of Slesvig where Danish was spoken by a majority conveniently voted themselves ‘home’. -

Crash Course Week

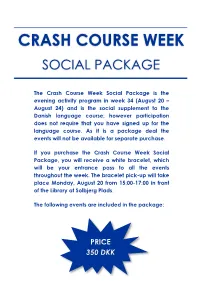

CRASH COURSE WEEK SOCIAL PACKAGE The Crash Course Week Social Package is the evening activity program in week 34 (August 20 – August 24) and is the social supplement to the Danish language course; however participation does not require that you have signed up for the language course. As it is a package deal the events will not be available for separate purchase. If you purchase the Crash Course Week Social Package, you will receive a white bracelet, which will be your entrance pass to all the events throughout the week. The bracelet pick-up will take place Monday, August 20 from 15:00-17:00 in front of the Library at Solbjerg Plads. The following events are included in the package: PRICE 350 DKK 2 DANISH ”HYGGE” This will be a night in the name of hygge. Hygge is a Danish concept which roughly describes that warm and fuzzy feeling when you are surrounded by good food and good company. The night will start out with a stand-up comedy show performed by two comedians Joe Eagan from Canada and Mikkel Rask from Denmark. They will take you on a hilarious ride through Danish culture which will give you a better understanding of the crazy Danes. After the stand-up comedy show the traditional Danish dish Røde Pølser Med Brød will be served at the CBS student bar Nexus. After the dinner you will have the rest of the night to mingle with your fellow exchange students in the bar. TIME: 19:00 – 23:00 LOCATION: SP202 Solbjerg Plads 3 2000 Frederiksberg DIRECTIONS: Take the metro to Frederiksberg Station. -

Leksikografi Og Excentricitet Thorleifur Gudmundsson Repp, En Islandsk Leksikograf

Leksikografi og excentricitet Thorleifur Gudmundsson Repp, en islandsk leksikograf af ordbogsredaktør, cand.mag. Jens Axelsen I 1995 er det 150 år siden der på Gyldendal udkom en ordbog; Dansk-Engelsk Ordbog af J.S. Ferrall & Thorl. Gudm. Repp, der fik stor betydning for dansk engelsk leksikografi. Den betød et brud med den hidtidige tradition som var præget af det 18. århundrede og indledningen til en mere moderne form for ordbog. Den var den første der havde et solidt fundament at bygge på, såvel for de danske ords vedkommende, nemlig Molbechs Dansk Ordbog fra 1833, som for oversættelsernes, da Ferrall var englænder, og Repp selv var særdeles velbe vandret i engelsk. Der er en ubrudt forbindelse fra den og op til Gyldendals nuværende røde dansk-engelske ordbog, og som redaktør af denne ordbog har jeg interesseret mig for redaktørerne af den gamle ordbog. Mens det var svært at finde ret mange oplysninger om Ferrall ud over hans fødsels- og dødsår, hans uddannelse (han havde medicinsk eksamen fra Edinburgh) og hans adresser i København, var det noget helt andet med hans islandske medforfatter, der viste sig at være et spændende bekendtskab, som også bekræftede min formodning om at der ofte er en sammenhæng mellem leksikografi og excentricitet. Når man ser tilbage i historien finder man adskillige eksempler på excentri ske leksikografer: den måske berømteste af dem alle, Dr Johnson, der udgav sin Dictionary of the English Language i 1755, var bestemt ikke helt almindelig, og også i hans leksikografiske arbejde er der glimt af excentricitet. Velkendt er hans definition i ordbogen af lexicographer: "A writer of dictionaries, a harmless drudge", og af oats: "A grain which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people".