Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege's 1993 Translation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001. Preface This bibliography attempts to list all substantial autobiographies, biographies, festschrifts and obituaries of prominent oceanographers, marine biologists, fisheries scientists, and other scientists who worked in the marine environment published in journals and books after 1922, the publication date of Herdman’s Founders of Oceanography. The bibliography does not include newspaper obituaries, government documents, or citations to brief entries in general biographical sources. Items are listed alphabetically by author, and then chronologically by date of publication under a legend that includes the full name of the individual, his/her date of birth in European style(day, month in roman numeral, year), followed by his/her place of birth, then his date of death and place of death. Entries are in author-editor style following the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 14th ed., 1993). Citations are annotated to list the language if it is not obvious from the text. Annotations will also indicate if the citation includes a list of the scientist’s papers, if there is a relationship between the author of the citation and the scientist, or if the citation is written for a particular audience. This bibliography of biographies of scientists of the sea is based on Jacqueline Carpine-Lancre’s bibliography of biographies first published annually beginning with issue 4 of the History of Oceanography Newsletter (September 1992). It was supplemented by a bibliography maintained by Eric L. Mills and citations in the biographical files of the Archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD. -

“The New Look” in the History of Linguistics (1965)

“The New Look” in the History of Linguistics (1965) W. Keith Percival What follows here is a summary of a paper presented at the 128th Meeting of the Lin- guistic Circle of Madison on December 9, 1965. A complete typescript or manuscript has not survived. Fortunately, Jon Erickson, the recorder of the Linguistic Circle of Madison, entered this detailed digest of the paper into the Linguistic Circle’s minutes. At the request of Charles T. Scott, the secretary of the Madison Linguistics department graciously provided me with copies of the minutes referring to all the papers that I presented to the Linguistic Circle in the years 1965- 69 while I was teaching linguistics at the Milwaukee campus of the University of Wisconsin. Needless to say, I feel much indebted to Professors Scott and Erickson, and to the departmental secretary. ---------- The purpose of “‘The New Look’ in the History of Linguistics” was to review two stan- dard treatises on the history of linguistics, namely Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft in Deutschland by Theodor Benfey (1869), and Linguistic Science in the Nineteenth Century by Holger Pedersen (1931) . In spite of the way Theodor Benfey (1809–1881) implicitly outlined the subject matter of his book in the title [“History of Linguistics and Oriental Philology since the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, with a Retrospective Glance at Earlier Periods”], he in fact devoted much attention to linguistic studies spanning the entire period from the end of the medieval period to the beginning of the nineteenth century. In his so-called retrospective survey [Rückblick auf die früheren Zeiten ], he dealt with the Renaissance and the eighteenth century in remarkable detail. -

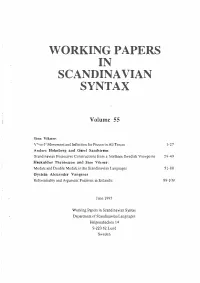

Working Papers in Scandina Vian Syntax

WORKING PAPERS IN SCANDINA VIAN SYNTAX Volume 55 Sten Vikner: V0-to-l0 Mavement and Inflection for Person in AllTenses 1-27 Anders Holmberg and Gorel Sandstrom: Scandinavian Possessive Construerions from a Northem Swedish Viewpoint 29-49 Hoskuldur Thrainsson and Sten Vikner: Modals and Double Modals in the Scandinavian Languages 51-88 Øystein Alexander Vangsnes Referentiality and Argument Positions in leelandie 89-109 June 1995 Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax Department of Scandinavian Languages Helgonabacken 14 S-223 62 Lund Sweden V0-TO-JO MOVEMENT AND INFLECTION FOR PERSON IN ALL TENSES Sten Vilener Institut furLinguistik/Germanistik, Universitat Stuttgart, Postfach 10 60 37, D-70049 Stuttgart, Germany E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACf Differentways are considered of formulating a conneelion between the strength of verbal inflectional morphology and the obligatory m ovement of the flnite verb to J• (i.e. to the lefl of a medial adverbial or of negation), and two main alternatives are anived at. One is from Rohrbacher (1994:108):V"-to-1• movement iff 151 and 2nd person are distinctively marked at least once. The other will be suggesled insection 3: v•-to-J• mavement iff all"core' tenses are inflectedfor person. It is argued that the latter approach has certain both conceptual and empirical advantages ( e.g. w hen considering the loss of v•-to-J• movement in English). CONTENTS 1. Introduction: v•-to-J• movement ...................................................................................................................................... -

Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present (Impact: Studies in Language and Society)

<DOCINFO AUTHOR ""TITLE "Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present"SUBJECT "Impact 18"KEYWORDS ""SIZE HEIGHT "220"WIDTH "150"VOFFSET "4"> Germanic Standardizations Impact: Studies in language and society impact publishes monographs, collective volumes, and text books on topics in sociolinguistics. The scope of the series is broad, with special emphasis on areas such as language planning and language policies; language conflict and language death; language standards and language change; dialectology; diglossia; discourse studies; language and social identity (gender, ethnicity, class, ideology); and history and methods of sociolinguistics. General Editor Associate Editor Annick De Houwer Elizabeth Lanza University of Antwerp University of Oslo Advisory Board Ulrich Ammon William Labov Gerhard Mercator University University of Pennsylvania Jan Blommaert Joseph Lo Bianco Ghent University The Australian National University Paul Drew Peter Nelde University of York Catholic University Brussels Anna Escobar Dennis Preston University of Illinois at Urbana Michigan State University Guus Extra Jeanine Treffers-Daller Tilburg University University of the West of England Margarita Hidalgo Vic Webb San Diego State University University of Pretoria Richard A. Hudson University College London Volume 18 Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert and Wim Vandenbussche Germanic Standardizations Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert Monash University Wim Vandenbussche Vrije Universiteit Brussel/FWO-Vlaanderen John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam/Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements 8 of American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Germanic standardizations : past to present / edited by Ana Deumert, Wim Vandenbussche. -

From Semantics to Dialectometry

Contents Preface ix Subjunctions as discourse markers? Stancetaking on the topic ‘insubordi- nate subordination’ Werner Abraham Two-layer networks, non-linear separation, and human learning R. Harald Baayen & Peter Hendrix John’s car repaired. Variation in the position of past participles in the ver- bal cluster in Duth Sjef Barbiers, Hans Bennis & Lote Dros-Hendriks Perception of word stress Leonor van der Bij, Dicky Gilbers & Wolfgang Kehrein Empirical evidence for discourse markers at the lexical level Jelke Bloem Verb phrase ellipsis and sloppy identity: a corpus-based investigation Johan Bos 7 7 Om-omission Gosse Bouma 8 Neural semantics Harm Brouwer, Mathew W. Crocker & Noortje J. Venhuizen 7 9 Liberating Dialectology J. K. Chambers 8 0 A new library for construction of automata Jan Daciuk 9 Generating English paraphrases from logic Dan Flickinger 99 Contents Use and possible improvement of UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Lan- guages in Danger Tjeerd de Graaf 09 Assessing smoothing parameters in dialectometry Jack Grieve 9 Finding dialect areas by means of bootstrap clustering Wilbert Heeringa 7 An acoustic analysis of English vowels produced by speakers of seven dif- ferent native-language bakgrounds Vincent J. van Heuven & Charlote S. Gooskens 7 Impersonal passives in German: some corpus evidence Erhard Hinrichs 9 7 In Hülle und Fülle – quantiication at a distance in German, Duth and English Jack Hoeksema 9 8 he interpretation of Duth direct speeh reports by Frisian-Duth bilin- guals Franziska Köder, J. W. van der Meer & Jennifer Spenader 7 9 Mining for parsing failures Daniël de Kok & Gertjan van Noord 8 0 Looking for meaning in names Stasinos Konstantopoulos 9 Second thoughts about the Chomskyan revolution Jan Koster 99 Good maps William A. -

Online Activation of L1 Danish Orthography Enhances Spoken Word Recognition of Swedish

Nordic Journal of Linguistics (2021), page 1 of 19 doi:10.1017/S0332586521000056 ARTICLE Online activation of L1 Danish orthography enhances spoken word recognition of Swedish Anja Schüppert1 , Johannes C. Ziegler2, Holger Juul3 and Charlotte Gooskens1 1Center for Language and Cognition Groningen, University of Groningen, P.O. Box 716, 9700 AS Groningen, The Netherlands; Email: [email protected], [email protected] 2Laboratoire de Psychologie Cognitive/CNRS, Aix-Marseille University, 3, place Victor Hugo, 13003 Marseille, France; Email: [email protected] 3Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics, University of Copenhagen, Emil Holms Kanal 2, 2300 Copenhagen S, Denmark; Email: [email protected] (Received 6 June 2020; revised 9 March 2021; accepted 9 March 2021) Abstract It has been reported that speakers of Danish understand more Swedish than vice versa. One reason for this asymmetry might be that spoken Swedish is closer to written Danish than vice versa. We hypothesise that literate speakers of Danish use their ortho- graphic knowledge of Danish to decode spoken Swedish. To test this hypothesis, first- language (L1) Danish speakers were confronted with spoken Swedish in a translation task. Event-related brain potentials (ERPs) were elicited to study the online brain responses dur- ing decoding operations. Results showed that ERPs to words whose Swedish pronunciation was inconsistent with the Danish spelling were significantly more negative-going than ERPs to words whose Swedish pronunciation was consistent with the Danish spelling between 750 ms and 900 ms after stimulus onset. Together with higher word-recognition scores for consistent items, our data provide strong evidence that online activation of L1 orthography enhances word recognition of spoken Swedish in literate speakers of Danish. -

The Manuscript Collection of Rasmus Christian Rask

Tabularia Sources écrites des mondes normands médiévaux Autour des sagas : manuscrits, transmission et écriture de l’histoire | 2016 The library of the genius: The manuscript collection of Rasmus Christian Rask La bibliothèque d’un génie : la collection de manuscrits de Rasmus Christian Rask La Biblioteca di un genio: la collezione di manoscritti di Rasmus Christian Rask Silvia Hufnagel Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tabularia/2666 DOI: 10.4000/tabularia.2666 ISSN: 1630-7364 Publisher: CRAHAM - Centre Michel de Boüard, Presses universitaires de Caen Electronic reference Silvia Hufnagel, « The library of the genius: The manuscript collection of Rasmus Christian Rask », Tabularia [Online], Autour des sagas : manuscrits, transmission et écriture de l’histoire, Online since 17 November 2016, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tabularia/2666 ; DOI : 10.4000/tabularia.2666 CRAHAM - Centre Michel de Boüard h e library of the genius: h e manuscript collection of Rasmus Christian Rask La bibliothèque d’un génie: la collection de manuscrits de Rasmus Christian Rask La Biblioteca di un genio: la collezione di manoscritti di Rasmus Christian Rask Silvia Hufnagel Austrian Academy of Sciences, Institute for Medieval Research [email protected] Abstract: h e Arnamagnæan Institute at the University of Copenhagen houses the Old Norse- Icelandic manuscript collection of the famous Danish linguist Rasmus Rask (1787-1832) that comprises 127 post-medieval volumes. h e topics covered in the manuscripts rel ect Rask’s widespread interests and range from literature to non-i ctional works, such as linguistics, history, law and liturgy. It seems that Rask’s large network of friends and acquaintances was of help in his ef orts of acquiring manuscripts. -

Current Transformations in Norwegian Higher Education

Research & Occasional Paper Series: CSHE.2.02 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY http://ishi.lib.berkeley.edu/cshe/ CURRENT TRANSFORMATIONS 1 IN NORWEGIAN HIGHER EDUCATION March 2002 Kim Gunnar Helsvig Research Fellow Forum for University History Dept. of History, University of Oslo Pb.1008 Blindern, N-0315 Oslo Norway tel:+47 22856873 fax: +47 22855278 [email protected] http://www.hf.uio.no/hi/prosjekter/univhist/ Copyright 2002 Kim Gunnar Helsvig, all rights reserved. This working paper is not to be quoted without the permission of the author. ABSTRACT This article revises Norwegian higher education debate from the publication of a radical reform proposal made by a government committee in May 2000 until the closure of the reform process in the parliament in May 2001. It is argued that a great rhetorical divide between neo-liberal and Humboldtian concepts of higher education characterized the debate, and that this to some extent distorted the coherence of the final solutions. Nevertheless, it is maintained that the reform is quite likely to instigate a period of profound changes in the national higher education system. Introduction In May 2000, a Norwegian government appointed committee presented a report on higher education with the selling title Freedom with responsibility.2 In this report recommendations for reform were made that – if carried out – would lead to changes in the Norwegian higher education system that in many respects would fundamentally break with national traditions. In the first section of this article I will therefore briefly outline the development and the current state of higher education in Norway, and then go on to present the reforms proposed by the committee. -

Denmark — Backgrounds

LIBER Manuscript Librarians Group Manuscript Librarians Group Denmark — Backgrounds Ivan Boserup (Royal Library, Copenhagen) Contents: Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen (collection history; major collections; catalogues and digitisation; other collections). — Statsbibliotekets Håndskriftsamling, Aarhus. — Danmarks Kunstbibliotek, Copenhagen. — Dansk Folkemindesamling, Copenhagen. — Den Arnamagnæanske Samling, Copenhagen. — Karen Brahes Bibliotek, Odense. — Statens Arkiver, Copenhagen. — Det Danske Udvandrerarkiv, Aalborg. — Arbejderbevægelsens Arkiv, Copenhagen. — Arktisk Instituts Arkiv, Copenhagen. — Kvindehistorisk Samling, Aarhus. — Niels Bohr Arkivet, Copenhagen. — Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen. — Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen. Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen (collection history) 1. The Royal Library was founded by King Frederik III (1609-1670) in the 1650s by merging his private library with that inherited from his predecessors, and in particular by acquiring four important private libraries, The Bibliotheca Regia in the Castle of Copenhagen in his time housed more than 100 manuscripts, and was confirmed as National Library in the Danish Legal Deposit Law of 1697. Booty of war and acquisitions of whole manuscript collections from private scholars and collectors characterise the early 18th century. The Great Fire of Copenhagen, which spared the Royal Library and the Royal Archives, but annihilated the University Library, marks an intensification of manuscript acquisitions both in the private and in the public sphere. Besides important Icelandic codices, all the Danish medieval sources collected over the years by successive specially appointed Royal Historiographers were destroyed. New manuscript collections were established for the University Library, largely through private donations, but daring auction purchases and acquisitions of whole manuscript collections were also made, both privately and by the state. 2. The Collectio Regia or Old Royal Collection of manuscripts had grown to ca. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Daňo Juraj - (2007) do výtvarného života vstúpil tesne po 2. svetovej vojne; v tvorbe prekonal niekoľko vývojových zmien, od kompozícií dôsledne a detailne interpretujúcich farebné a tvarové bohatstvo krajiny, cez krajinu s miernou farebnou, tvarovou i rukopisnou expresionistickou nadsádzkou, až ku kompozíciám redukujúcim tvary na ich geometrickú podstatu; tak v krajinárskych, ako aj vo figurálnych kompozíciách, vyskytujúcich sa v celku jeho tvorby len sporadicky, farebne dominuje modro – fialovo – zelený akord; po prekonaní experimentálneho obdobia, v ktorom dospel k výrazne abstrahovanej forme na hranici informačného prejavu, sa upriamoval na kompozície, v ktorých sa kombináciou techník usiloval o podanie spoločensky závažnej problematiky; vytvoril aj celý rad monumentálno-dekoratívnych kompozícií; od roku 1952 bol členom východoslovenského kultúrneho spolku Svojina, zároveň členom skupiny Roveň; v roku 1961 sa stal členom Zväzu slovenských výtvarných umelcov; od roku 1969 pôsobil ako umelec v slobodnom povolaní; v roku 1984 mu bol udelený titul zaslúžilého umelca J. Daňo: Horúca jeseň J. Daňo: Za Bardejovom Heslo DANO – DAR Strana 1 z 22 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia J. Daňo J. Daňo: Drevenica Heslo DANO – DAR Strana 2 z 22 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia J. Daňo: J. Daňo Heslo DANO – DAR Strana 3 z 22 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia J. Daňo: Ulička so sypancom J. Daňo: Krajina Daňový peniaz - Zaplatenie dane cisárovi dánska loď - herring-buss Dánsko - dánski ilustrátori detských kníh - pozri L. Moe https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Danish_children%27s_book_illustrators M Christel Marotta Louis Moe O Ib Spang Olsen dánski krajinári - Heslo DANO – DAR Strana 4 z 22 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Danish_landscape_painters dánski maliari - pozri C. -

The Danish Spelling Dictionary Revis(It)Ed Henrik Lorentzen Dept

Orthographical Dictionaries: How Much Can You Expect? The Danish Spelling Dictionary Revis(it)ed Henrik Lorentzen Dept. for Digital Dictionaries and Text Corpora, DSL Society for Danish Language and Literature Orthographical dictionaries constitute a particular and rather specialised subclass of dictionaries. This contribution offers a presentation of the ongoing revision of a spelling dictionary (for Danish) and a discussion of some of the general and specific issues that have arisen during the project. Firstly, the background is sketched, a brief overview of the many editorial changes is provided, and lemma selection, variant forms and definitions are discussed in some detail. Secondly, the field of orthographical dictionaries in Denmark is compared to some other countries of northern Europe. Finally, the conclusion engages in a discussion of the necessity of this particular type of dictionary. 1. Introduction The tradition of official orthographical dictionaries for Danish goes back about 140 years. The first official spelling dictionary was published in 1872 and authorised by the Ministry for Ecclesiastical Affairs and Public Instruction (Kultusministeriet). For the following 80 years, a whole series of spelling dictionaries succeeded each other, edited by different scholars and teachers, but all of them officially recommended by the government. In 1955, the Danish Language Council was established as a governmental institution under the Ministry of Culture, and among its primary tasks it was to codify and publish the official orthographical standard of Danish in a spelling dictionary. The first dictionary edited by the Language Council was published in 1986 under the title of Retskrivningsordbogen (The Orthographical Dictionary, henceforth RO), two revised editions came out in 1996 and 2001, and now a completely updated version is planned for 2011. -

CROSS-LINGUISTIC STUDY of SPELLING in ENGLISH AS a FOREIGN LANGUAGE: the ROLE of FIRST LANGUAGE ORTHOGRAPHY in EFL SPELLING a Di

CROSS-LINGUISTIC STUDY OF SPELLING IN ENGLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE: THE ROLE OF FIRST LANGUAGE ORTHOGRAPHY IN EFL SPELLING A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Nadezda Lvovna Dich August 2011 © 2011 Nadezda Lvovna Dich CROSS-LINGUISTIC STUDY OF SPELLING IN ENGLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE: THE ROLE OF FIRST LANGUAGE ORTHOGRAPHY IN EFL SPELLING Nadezda Lvovna Dich, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The study investigated the effects of learning literacy in different first languages (L1s) on the acquisition of spelling in English as a foreign language (EFL). The hypothesis of the study was that given the same amount of practice, English learners from different first language backgrounds would differ on their English spelling proficiency because different orthographies “train” spelling skills differently and therefore the opportunities for positive cross-linguistic transfer that benefits English spelling would differ across L1s. The study also predicted that cross-linguistic differences in English spelling would not be the same across different components of spelling proficiency because cross-linguistic transfer would affect some skills involved in spelling competence, but not others. The study tested native speakers of Danish, Italian, and Russian with intermediate to advanced EFL proficiency. The three languages were chosen for this study based on the differences in native language spelling skills required to learn the three orthographies. One hundred Danish, 98 Italian, and 104 Russian university students, as well as a control group of 95 American students were recruited to participate in the web-based study, which was composed of four tasks testing four skills previously identified as components of English spelling proficiency: irregular word spelling, sensitivity to morphological spelling cues, sensitivity to context-driven probabilistic orthographic patterns, and phonological awareness.