Lashing Cultural Nationalisms: the 19Th

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

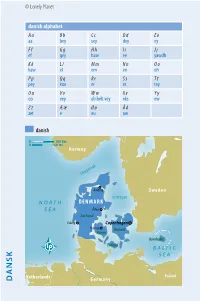

Danish Alphabet DENMARK Danish © Lonely Planet

© Lonely Planet danish alphabet A a B b C c D d E e aa bey sey dey ey F f G g H h I i J j ef gey haw ee yawdh K k L l M m N n O o kaw el em en oh P p Q q R r S s T t pey koo er es tey U u V v W w X x Y y oo vey do·belt vey eks ew Z z Æ æ Ø ø Å å zet e eu aw danish 0 100 km 0 60 mi Norway Skagerrak Aalborg Sweden Kattegat NORTH DENMARK SEA Århus Jutland Esberg Copenhagen Odense Zealand Funen Bornholm Lolland BALTIC SEA Poland Netherlands Germany DANSK DANSK DANISH dansk introduction What do the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard have in common (apart from pondering the complexities of life and human character)? Danish (dansk dansk), of course – the language of the oldest European monarchy. Danish contributed to the English of today as a result of the Vi- king conquests of the British Isles in the form of numerous personal and place names, as well as many basic words. As a member of the Scandinavian or North Germanic language family, Danish is closely related to Swedish and Norwegian. It’s particularly close to one of the two official written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål – Danish was the ruling language in Norway between the 15th and 19th centuries, and was the base of this modern Norwegian literary language. In pronunciation, however, Danish differs considerably from both of its neighbours thanks to its softened consonants and often ‘swallowed’ sounds. -

Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein BONEBANK: a GERMAN- DANISH BIOBANK for STEM CELLS in BONE HEALING

Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein BONEBANK: A GERMAN- DANISH BIOBANK FOR STEM CELLS IN BONE HEALING ScanBalt Forum, Tallin, October 2017 PROJECT IN A NUTSHELL Start: 1th September 2015 End: 29 th February 2019 Duration: 36 months Total project budget: 2.377.265 EUR, 1.338.876 EUR of which are Interreg funding 3 BONEBANK: A German-Danish biobank for stem cells in bone healing 20. Oktober 2017 PROJECT STRUCTURE Project Partners University Medical Centre Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck (Lead Partner) Odense University Hospital Stryker Trauma Soventec Life Science Nord Network partners Syddansk Sundhedsinnovation WelfareTech Project Management DSN – Connecting Knowledge 4 BONEBANK: A German-Danish biobank for stem cells in bone healing 20. Oktober 2017 OPPORTUNITIES, AMBITION AND GOALS • Research on stem cells is driving regenerative medicine • Availability of high-quality bone marrow stem cells for patients and research is limited today • Innovative approach to harvest bone marrow stem cells during routine operations for fracture treatment • Facilitating access to bone marrow stem cells and driving research and innovation in Germany- Denmark Harvesting of bone marrow stem cells during routine operations in the university hospitals Odense and Lübeck Cross-border biobank for bone marrow stem cells located in Odense and Lübeck Organisational and exploitation model for the Danish-German biobank providing access to bone marrow stem cells for donators, patients, public research and companies 5 BONEBANK: A German-Danish biobank for stem cells in bone healing 20. Oktober 2017 ACHIEVEMENTS SO FAR Harvesting of 53 samples, both in Denmark and Germany Donors/Patients Most patients (34) are over 60 years old 19 women 17 women Germany Isolation of stem cells possible Denmark 7 men 10 men Characterization profiles of stem cells vary from individual to individual Age < 60 years > 60 years 27 7 9 10 women men 6 BONEBANK: A German-Danish biobank for stem cells in bone healing 20. -

(Modern Philosophy) Part I: Fichte to Hegel 9. Walter Benjamin, Der

Notes 1 Idealism and the Justification of the Image 1. J.G. Fichte, The Vocation of Man (New York: Bobbs Merrill, 1956), p.80 (adapted). 2. Idem, The Science of Knowledge (New York: Appleton, Century Crofts, 1970), p.188. 3. Fichte (1956), pp.81f. 4. Ibid., pp.98f. 5. Ibid., pp.124f. 6. Ibid., p.147. 7. For example, the so-called 'Atheismusstreit'. See: F. Copleston, A History of Philosophy, Vol. V, II (Modern Philosophy) Part I: Fichte to Hegel (New York: Doubleday, 1965), pp.lOOff. 8. Friedrich Schlegel, Kritische Schriften (Miinchen: Carl Hanser, 1956), p.46. 9. Walter Benjamin, Der Begriff der Kunstkritik in der Deutschen Romantik in Gesammelten Schriften 1:1 (Frankfurt am Main, 1972), p.26. 10. Quoted in Benjamin (1972), p.37. 11. F. Schlegel, Lucinde (Stuttgart: Reclam, 1963), p.35. 12. F.J.W. Schelling, System of Transcendental Idealism (Charlottesville: Uni versity of Viriginia Press, 1978), p.219. 13. Ibid., p.232. 14. Henrik Steffens, Inledning til Philosophiske Forelasninger i K9benhavn (1803) (New edn) K0benhavn: Gyldendal, 1905), p.21. 15. Ibid., pp.21f. 16. Ibid., p.22. 17. One of the best summaries of Grundtvig's thought in English remains E.L. Allen, Bishop Grundtvig: A Prophet of the North (London: James Clarke, 1949). James Clarke have also published (more recently) an anthology of Grundtvig's writings. A sign of increasing Anglo-Saxon awareness of Grundtvig's significance is the recently formed Anglo Danish conference Grundtvig and England. 18. Henning Fenger, Kierkegaard: The Myths and Their Origins (Newhaven: Yale University Press, 1980), p.84. 19. -

“The New Look” in the History of Linguistics (1965)

“The New Look” in the History of Linguistics (1965) W. Keith Percival What follows here is a summary of a paper presented at the 128th Meeting of the Lin- guistic Circle of Madison on December 9, 1965. A complete typescript or manuscript has not survived. Fortunately, Jon Erickson, the recorder of the Linguistic Circle of Madison, entered this detailed digest of the paper into the Linguistic Circle’s minutes. At the request of Charles T. Scott, the secretary of the Madison Linguistics department graciously provided me with copies of the minutes referring to all the papers that I presented to the Linguistic Circle in the years 1965- 69 while I was teaching linguistics at the Milwaukee campus of the University of Wisconsin. Needless to say, I feel much indebted to Professors Scott and Erickson, and to the departmental secretary. ---------- The purpose of “‘The New Look’ in the History of Linguistics” was to review two stan- dard treatises on the history of linguistics, namely Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft in Deutschland by Theodor Benfey (1869), and Linguistic Science in the Nineteenth Century by Holger Pedersen (1931) . In spite of the way Theodor Benfey (1809–1881) implicitly outlined the subject matter of his book in the title [“History of Linguistics and Oriental Philology since the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, with a Retrospective Glance at Earlier Periods”], he in fact devoted much attention to linguistic studies spanning the entire period from the end of the medieval period to the beginning of the nineteenth century. In his so-called retrospective survey [Rückblick auf die früheren Zeiten ], he dealt with the Renaissance and the eighteenth century in remarkable detail. -

Speculative Geology

15 Speculative Geology DALE E. SNOW We are not at peace with nature now. Whether it is the record-setting rain on the east coast or the raging wildfires in the west, distant news of melting permafrost or bleaching coral reefs, or the unexpected eruption of Mount Kilauea a few miles from here, things seem increasingly, and increasingly violently, out of control. I would like to suggest that there are resources in Schelling’s Naturphilosophie we can use in the twenty-first century to help us think differently about both the power of nature and our own relationship to it. Although Schelling saw himself, and was seen by many, as antagonistic toward the mechanical science of his own time, it would be a mistake—and a missed opportunity—to see his view as a mere Romantic reaction. It is a speculative rethinking of the idea of nature itself that finds a place for even those phenomena which seem most distant and alien. Schelling described his philosophy of nature as “speculative physics” both to distinguish it from what he calls the dogmatic or mechanistic model of nature, and to announce a new approach to natural science, concerned with the original causes of motion in nature (SW III: 275). Since every “natural phenomenon … stands in connection with the last conditions of nature” (SW III: 279), speculative physics can bring us to an understanding of nature as a system. Geology presents an illuminating case of this approach, as can be seen from Schelling’s characteristically enthusiastic introduction to a paper published by Henrik Steffens in Schelling’sJournal of Speculative Physics (Zeitschrift für speculative Physik) on the oxidization and deoxidization of the earth.1 After praising Steffens’ work on a new and better founded science of geology, Schelling reflects darkly on the too long dominant mechanical approach to geology. -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

CEMENT for BUILDING with AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Portland Aalborg Cover Photo: the Great Belt Bridge, Denmark

CEMENT FOR BUILDING WITH AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Cover photo: The Great Belt Bridge, Denmark. AALBORG Aalborg Portland Holding is owned by the Cementir Group, an inter- national supplier of cement and concrete. The Cementir Group’s PORTLAND head office is placed in Rome and the Group is listed on the Italian ONE OF THE LARGEST Stock Exchange in Milan. CEMENT PRODUCERS IN Cementir's global organization is THE NORDIC REGION divided into geographical regions, and Aalborg Portland A/S is included in the Nordic & Baltic region covering Aalborg Portland A/S has been a central pillar of the Northern Europe. business community in Denmark – and particularly North Jutland – for more than 125 years, with www.cementirholding.it major importance for employment, exports and development of industrial knowhow. Aalborg Portland is one of the largest producers of grey cement in the Nordic region and the world’s leading manufacturer of white cement. The company is at the forefront of energy-efficient production of high-quality cement at the plant in Aalborg. In addition to the factory in Aalborg, Aalborg Portland includes five sales subsidiaries in Iceland, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia. Aalborg Portland is part of Aalborg Portland Holding, which is the parent company of a number of cement and concrete companies in i.a. the Nordic countries, Belgium, USA, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia and China. Additionally, the Group has acti vities within extraction and sales of aggregates (granite and gravel) and recycling of waste products. Read more on www.aalborgportlandholding.com, www.aalborgportland.dk and www.aalborgwhite.com. Data in this brochure is based on figures from 2017, unless otherwise stated. -

Evidence from Hamburg's Import Trade, Eightee

Economic History Working Papers No: 266/2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Economic History Department, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, London, UK. T: +44 (0) 20 7955 7084. F: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC HISTORY WORKING PAPERS NO. 266 – AUGUST 2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Email: [email protected] Abstract The study combines information on some 180,000 import declarations for 36 years in 1733–1798 with published prices for forty-odd commodities to produce aggregate and commodity specific estimates of import quantities in Hamburg’s overseas trade. In order to explain the trajectory of imports of specific commodities estimates of simple import demand functions are carried out. Since Hamburg constituted the principal German sea port already at that time, information on its imports can be used to derive tentative statements on the aggregate evolution of Germany’s foreign trade. The main results are as follows: Import quantities grew at an average rate of at least 0.7 per cent between 1736 and 1794, which is a bit faster than the increase of population and GDP, implying an increase in openness. Relative import prices did not fall, which suggests that innovations in transport technology and improvement of business practices played no role in overseas trade growth. -

Queen Victoria's Family Tree

Married Divorced QUEEN VICTORIA’S FAMILY TREE Affair Assassinated Legitimate children Twice in chart Illegitimate children King or Queen Albert, Queen Prince Consort Victoria 1819-1861 1819-1901 Topic of a Bax of Things blog Prince Arthur Princess Alice Prince Alfred Princess Helena Princess Louise Duke of Prince Leopold Princess Beatrice of the United Duke of Saxe- of the United Duchess of Argyll Connaught Duke of Albany of the United Vicky EDWARD VII Kingdom Coburg and Gotha Kingdom and Strathearn Kingdom Princess Royal King of the 1843-1878 1844-1900 1846-1923 1848-1939 1853-1884 1857-1944 United Kingdom 1850-1942 1840-1901 1841-1910 Frederick III Ludwig Maria Prince Christian John Campbell Princess Louise Margaret Princess Helena Prince Henry German Emperor Alexandra GD of Hesse Grand Duchess of Russia of Schleswig-Holstein Duke of Argyll of Prussia of Waldeck and Pyrmont of Battenberg of Denmark 1837-1892 1853-1920 1831-1917 1845-1914 1860-1917 1861-1922 1858-1896 1831-1888 1844-1925 Wilhelm II Prince Princess Victoria Alfred, Hereditary Prince Princess Margaret Princess Alice Alexander Mountbatten German Emperor & Prince Christian Victor Albert Victor of Hesse and by Rhine of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha of Connaught of Albany Marquess of Carisbrooke King of Prussia 1867-1900 1864-1892 1863-1950 1874-1899 1882-1920 1883-1981 1886-1960 1859-1941 1) Princess Augusta of Engaged to Prince Louis Gustav VI Adolf Alexander Cambridge Schleswig-Holstein (1858-1821) Marie Albert, Lady Irene Denison Mary of Teck of Battenberg King of Sweden 1st -

Wars Between the Danes and Germans, for the Possession Of

DD 491 •S68 K7 Copy 1 WARS BETWKEX THE DANES AND GERMANS. »OR TllR POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. BV t>K()F. ADOLPHUS L. KOEPPEN FROM THE "AMERICAN REVIEW" FOR NOVEMBER, U48. — ; WAKS BETWEEN THE DANES AND GERMANS, ^^^^ ' Ay o FOR THE POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. > XV / PART FIRST. li>t^^/ On feint d'ignorer que le Slesvig est une ancienne partie integTante de la Monarchie Danoise dont I'union indissoluble avec la couronne de Danemarc est consacree par les garanties solennelles des grandes Puissances de I'Eui'ope, et ou la langue et la nationalite Danoises existent depuis les temps les et entier, J)lus recules. On voudrait se cacher a soi-meme au monde qu'une grande partie de la popu- ation du Slesvig reste attacliee, avec une fidelite incbranlable, aux liens fondamentaux unissant le pays avec le Danemarc, et que cette population a constamment proteste de la maniere la plus ener- gique centre une incorporation dans la confederation Germanique, incorporation qu'on pretend medier moyennant une armee de ciuquante mille hommes ! Semi-official article. The political question with regard to the ic nation blind to the evidences of history, relations of the duchies of Schleswig and faith, and justice. Holstein to the kingdom of Denmark,which The Dano-Germanic contest is still at the present time has excited so great a going on : Denmark cannot yield ; she has movement in the North, and called the already lost so much that she cannot submit Scandinavian nations to arms in self-defence to any more losses for the future. The issue against Germanic aggression, is not one of a of this contest is of vital importance to her recent date. -

Coastal Living in Denmark

To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Coastal living in Denmark © Daniel Overbeck - VisitNordsjælland To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. The land of endless beaches In Denmark, we look for a touch of magic in the ordinary, and we know that travel is more than ticking sights off a list. It’s about finding wonder in the things you see and the places you go. One of the wonders that we at VisitDenmark are particularly proud of is our nature. Denmark has wonderful beaches open to everyone, and nowhere in the nation are you ever more than 50km from the coast. s. 2 © Jill Christina Hansen To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Denmark and its regions Geography Travel distances Aalborg • The smallest of the Scandinavian • Copenhagen to Odense: Bornholm countries Under 2 hours by car • The southernmost of the • Odense to Aarhus: Under 2 Scandinavian countries hours by car • Only has a physical border with • Aarhus to Aalborg: Under 2 Germany hours by car • Denmark’s regions are: North, Mid, Jutland West and South Jutland, Funen, Aarhus Zealand, and North Zealand and Copenhagen Billund Facts Copenhagen • Video Introduction • Denmark’s currency is the Danish Kroner Odense • Tipping is not required Zealand • Most Danes speak fluent English Funen • Denmark is of the happiest countries in the world and Copenhagen is one of the world’s most liveable cities • Denmark is home of ‘Hygge’, New Nordic Cuisine, and LEGO® • Denmark is easily combined with other Nordic countries • Denmark is a safe country • Denmark is perfect for all types of travelers (family, romantic, nature, bicyclist dream, history/Vikings/Royalty) • Denmark has a population of 5.7 million people s. -

Dominik Hünniger: Power, Economics and the Seasons

Dominik Hünniger: Power, Economics and the Seasons. Local Differences in the Per- ception of Cattle Plagues in 18th Century Schleswig and Holstein Paper presented at the Rural History 2013 conference, Berne, 19th to 22nd August 2013. DRAFT - please do not quote. 1. Introduction “Diseases are ideas“1 - this seemingly controversial phrase by Jacalyn Duffin will guide my presentation today. This is not to say that diseases do not take biological as well as historical reality. They most definitely do, but their biological „reality“ is embellished and interpreted by culture. Hence, the cultural and social factors influencing diagnoses, definitions and contain- ment strategies are the main focus of my paper.2 In particular, I will focus on how historical containment policies concerning epidemics and epizootics were closely intertwined with questions of power, co-operation and conflicts. One always had to consider and interpret different interests in order to find appropriate and fea- sible containment policies. Additionally all endeavours to regulate the usually very severe consequences of epidemics could be contested by different historical actors. In this respect, current research on the contested nature of laws and ordinances in Early Modern Europe es- tablished the notion of state building processes from below through interaction.3 In addition, knowledge and experience were locally specific and the attempts of authorities to establish norms could be understood and implemented in very idiosyncratic ways.4 Hence, implementation processes almost always triggered conflicts and misunderstandings. At the same time, authorities as well as subjects were interested in compromise and adjustments. Here, Stefan Brakensiek„s work is especially relevant for the interpretation of the events dur- ing a cattle plague outbreak in mid-18th-century Schleswig and Holstein: in particular his the- 1 Duffin, Lovers (2005), p.