Speculative Geology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Modern Philosophy) Part I: Fichte to Hegel 9. Walter Benjamin, Der

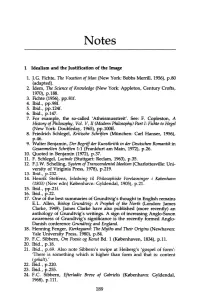

Notes 1 Idealism and the Justification of the Image 1. J.G. Fichte, The Vocation of Man (New York: Bobbs Merrill, 1956), p.80 (adapted). 2. Idem, The Science of Knowledge (New York: Appleton, Century Crofts, 1970), p.188. 3. Fichte (1956), pp.81f. 4. Ibid., pp.98f. 5. Ibid., pp.124f. 6. Ibid., p.147. 7. For example, the so-called 'Atheismusstreit'. See: F. Copleston, A History of Philosophy, Vol. V, II (Modern Philosophy) Part I: Fichte to Hegel (New York: Doubleday, 1965), pp.lOOff. 8. Friedrich Schlegel, Kritische Schriften (Miinchen: Carl Hanser, 1956), p.46. 9. Walter Benjamin, Der Begriff der Kunstkritik in der Deutschen Romantik in Gesammelten Schriften 1:1 (Frankfurt am Main, 1972), p.26. 10. Quoted in Benjamin (1972), p.37. 11. F. Schlegel, Lucinde (Stuttgart: Reclam, 1963), p.35. 12. F.J.W. Schelling, System of Transcendental Idealism (Charlottesville: Uni versity of Viriginia Press, 1978), p.219. 13. Ibid., p.232. 14. Henrik Steffens, Inledning til Philosophiske Forelasninger i K9benhavn (1803) (New edn) K0benhavn: Gyldendal, 1905), p.21. 15. Ibid., pp.21f. 16. Ibid., p.22. 17. One of the best summaries of Grundtvig's thought in English remains E.L. Allen, Bishop Grundtvig: A Prophet of the North (London: James Clarke, 1949). James Clarke have also published (more recently) an anthology of Grundtvig's writings. A sign of increasing Anglo-Saxon awareness of Grundtvig's significance is the recently formed Anglo Danish conference Grundtvig and England. 18. Henning Fenger, Kierkegaard: The Myths and Their Origins (Newhaven: Yale University Press, 1980), p.84. 19. -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

SKA-Athena Synergy White Paper

SKA-Athena Synergy White Paper SKA-Athena Synergy Team July 2018. Edited by: Francisco J. Carrera and Silvia Martínez-Núñez on behalf of the Athena Community Office. Revisions provided by: Judith Croston, Andrew C. Fabian, Robert Laing, Didier Barret, Robert Braun, Kirpal Nandra Authorship Authors Rossella Cassano (INAF-Istituto di Radioastronomia, Italy). • Rob Fender (University of Oxford, United Kingdom). • Chiara Ferrari (Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, France). • Andrea Merloni (Max-Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Germany). • Contributors Takuya Akahori (Kagoshima University, Japan). • Hiroki Akamatsu (SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, The Netherlands). • Yago Ascasibar (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain). • David Ballantyne (Georgia Institute of Technology, United States). • Gianfranco Brunetti (INAF-Istituto di Radioastronomia, Italy) and Maxim Markevitch (NASA-Goddard • Space Flight Center, United States). Judith Croston (The Open University, United Kingdom). • Imma Donnarumma (Agenzia Spaziale Italiana, Italy) and E. M. Rossi (Leiden Observatory, The • Netherlands). Robert Ferdman (University of East Anglia, United Kingdom) on behalf of the SKA Pulsar Science • Working Group. Luigina Feretti (INAF-Istituto di Radioastronomia, Italy) and Federica Govoni (INAF Osservatorio • Astronomico,Italy). Jan Forbrich (University of Hertfordshire, United Kingdom). • Giancarlo Ghirlanda (INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera and University Milano Bicocca, Italy). • Adriano Ingallinera (INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Catania, Italy). • Andrei Mesinger (Scuola Normale Superiore, Italy). • Vanessa Moss and Elaine Sadler (Sydney Institute for Astronomy/CAASTRO and University of Sydney, • Australia). Fabrizio Nicastro (Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma,Italy), Edvige Corbelli (INAF-Osservatorio As- • trofisico di Arcetri, Italy) and Luigi Piro (INAF, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Italy). Paolo Padovani (European Southern Observatory, Germany). • Francesca Panessa (INAF/Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Italy). -

The Idea of the University by Henrik Steffens (1809)

Henrik Steffens held these talks in 1808/1809 in the time of Napoleon’s occupation. The Emperor had just lifted his ban on university teaching. This was, amazingly enough, the formative time of Berlin University, an enterprise that would involve Steffens, Wilhelm von Humboldt, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Schleiermacher, Savigny and others. The lectures here were addressed to the students, not the administration or the prevailing governmental authorities. That in itself was quite a statement in these times. To Steffens, a university wasn’t supposed to be merely a trade school, but a place that opened you up, allowed you to blossom as an individual and helped you to learn to embrace the things of this world. We bring here in English, his first talk on the theme of what a university might be. --TCR The Idea of the University by Henrik Steffens (1809) Introduction These lectures were held at the commencement of the winter semester 1808/1809. Illness and various duties have, until now, prevented me from putting them into their current form. As my lectures are always extemporaneous, the reader will not find an exact reproduction of them but rather the succession of the ideas they contained. An esteemed person from abroad has spoken about the qualities of German Universities, as they must appear to a foreigner. One of the foremost minds of this nation has elaborated on the theme, deepening our understanding of it as it applies to this country1. It seems to me by no means superfluous to give the students themselves information about academic learning. -

Reading the Surface: the Danish Gothic of B.S. Ingemann, H.C

Reading the Surface: The Danish Gothic of B.S. Ingemann, H.C. Andersen, Karen Blixen and Beyond Kirstine Marie Kastbjerg A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Marianne Stecher. Chair Jan Sjaavik Marshall Brown Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Scandinavian Studies ©Copyright 2013 Kirstine Marie Kastbjerg Parts of chapter 7 are reprinted by permission of the publishers from “The Aesthetics of Surface: the Danish Gothic 1820-2000,” in Gothic Topographies ed. P.M. Mehtonen and Matti Savolainen (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013), pp. 153–167. Copyright © 2013 University of Washington Abstract Reading the Surface: The Danish Gothic of B.S. Ingemann, H.C. Andersen, Karen Blixen and Beyond Kirstine Marie Kastbjerg Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor in Danish Studies Marianne Stecher Department of Scandinavian Studies Despite growing ubiquitous in both the popular and academic mind in recent years, the Gothic has, perhaps not surprisingly, yet to be examined within the notoriously realism-prone literary canon of Denmark. This dissertation fills that void by demonstrating an ongoing negotiation of Gothic conventions in select works by canonical Danish writers such as B.S. Ingemann, Hans Christian Andersen, and Karen Blixen (Isak Dinesen), as well as contemporary writers such as Peter Høeg and Leonora Christina Skov. This examination does not only broaden our understanding of these culturally significant writers and the discourses they write within and against, it also adds to our understanding of the Gothic – an infamously malleable and indefinable literary mode – by redirecting attention to a central feature of the Gothic that has not received much critical attention: the emphasis on excess, spectacle, clichéd conventions, histrionic performances, its hyperbolic rhetorical style, and hyper-visual theatricality. -

Vor Berømte Landsmand – Seminar Om Henrik Steffens«, Universität Stavanger 18./19 September 2019

Janke Klok (Berlin/Groningen) über: »Vor berømte landsmand – Seminar om Henrik Steffens«, Universität Stavanger 18./19 September 2019 Tagungsbericht Das Seminar war als Auftakt für die Feierlichkeiten zum 250. Geburtstag von Henrik Steffens (1773–1845) in Stavanger im Jahr 2023 konzipiert und fand im Rahmen vom Kapittel statt, Stavangers jährlichem internationalen Festival für Literatur und Meinungsfreiheit (18.–22. September 2019). Ganz bewusst hatten die Veranstalter mit Blick auf das Jubiläum des Philosophen sich an ein breiteres Publikum gewandt, schließlich ist Steffens auch in seiner Geburtsstadt Stavanger eine relativ unbekannte Größe. Neuausgaben und Monografien belegen jedoch in den letzten Jahren (ebenso wie die beiden vorhergehenden Steffens-Seminare 2017 in Oslo und 2018 in Berlin) ein zunehmendes Interesse an Steffens – und dieses Interesse sollte in Stavanger weiter geweckt werden. Vor unerwartet großem und aufmerksamem Publikum versuchten der norwegische Schriftsteller TORE RENBERG sowie dänische, deutsche und norwegische Forscher_innen den Naturphilosophen, Novellenautor und politischen Professor einzusortieren, taucht er doch in der Philosophiegeschichte allenfalls als ein Begleiter Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schellings und in der Literaturwissenschaft als derjenige auf, der die Romantik nach Dänemark gebracht haben soll. Tore Renberg eröffnete in seiner ihm eigenen bekannten Art das Symposium: »Koffor i hekkan ska me bry oss om Henrik Steffens i dag, egentlig?« (»Warum zum Teufel soll ich mir eigentlich heute noch etwas aus Henrik Steffens machen?«) Auf seine Frage nach der Bedeutung von Henrik Steffens für die europäische Philoso- phie- und Kulturgeschichte gingen anschließend vier Wissenschaftler_innen ein. BERND HENNINGSEN (Humboldt- Universität zu Berlin) beleuchtete Henrik Steffens’ politische Bedeutung: »Henrik Steffens – en altmuligmann i omveltningstider. En innføring« (»Henrik Steffens – ein ›Mann für alles Mögliche‹ in Umbruchzeiten. -

Lutheran Revival and National Education in Denmark: the Religious Background of N

Scandinavica Vol 58 No 1 2019 Lutheran Revival and National Education in Denmark: The Religious Background of N. F. S. Grundtvig’s Educational Ideas Grażyna Szelągowska Warsaw University Abstract N. F. S. Grundtvig’s idea of national education has usually been regarded as a part of the history of adult education or as a complex of national ideas. This article takes into consideration that Grundtvig was first and foremost a clergyman, a founder of grundtvigianism and of the Grundtvigian revival movement. It presents a new perspective on the Lutheran background of Grundtvig’s educational programme, and its impact on the shaping of a civic society in Denmark. A religious revival which Grundtvig underwent during the first decades of the nineteenth century shaped the background of his educational programmes. Keywords N. F. S. Grundtvig, Lutheran revival, Grundtvigianism, national education, education in Denmark 6 Scandinavica Vol 58 No 1 2019 Introduction The nineteenth–century modernisation process in the Scandinavian countries has usually been presented as an example of a rather unique interplay of various agents: a peaceful transition from absolutist to democratic systems, the emergence of a free market economy, a crucial role for the state and the development of the underpinnings of the Nordic welfare model, a special position for the Lutheran churches, a wide spectrum of various popular movements, and the growth of civic society. The process of building a modern national identity is common to all those forms of modernisation, however different in particular Nordic countries. Romantic philosophy, with its sympathy for nationality and national identity (and even the idea of a new Nordic union: Scandinavianism), constituted a basis for the emergence of nineteenth–century social movements like national and pan–national organisations, popular education and folk high schools. -

Achievement of 15-Year-Olds in England: PISA 2006 National Report.’ (OECD Programme for International Student Assessment)

Achievement of 15-Year- Olds in England: PISA 2015 National Report December 2016 John Jerrim and Nikki Shure. UCL Institute of Education. Contents Acknowledgements 3 Executive summary 4 Chapter 1. Introduction 11 Chapter 2. Achievement in science 23 Chapter 3. Achievement in different aspects of scientific literacy 47 Chapter 4. Achievement in mathematics 64 Chapter 5. Achievement in reading 83 Chapter 6. Variation in PISA scores by pupil characteristics 101 Chapter 7. Differences in achievement between schools 117 Chapter 8. School management and resources 129 Chapter 9. Pupils’ experiences of their time in science classes at school 146 Chapter 11. PISA across the UK 181 Appendix A. Background to the PISA study 207 Appendix B. Sample design and response rates 218 Appendix C. Testing statistical significance in PISA across cycles 224 Appendix D. The conversion of PISA scores into years of schooling 227 Appendix E. PISA 2015 mean scores 228 Appendix F. Long-term trends in PISA scores 231 Appendix G. Mean scores in the science sub-domains 236 Appendix H. List of figures 239 Appendix I. List of tables 243 2 Acknowledgements This report represents a multi-team effort. We are grateful to the teams at Educational Testing Service (ETS), Westat, cApStAn Linguistic Control, Pearson and the German Institute for International Education Research (DIPF) for their support and guidance throughout the project. In England we are grateful to the team at the Department for Education that oversaw the work, in particular Adrian Higginbotham, Emily Knowles, Bethan Knight, Joe Delafield and David Charlton. The team at RM Education (RM) managed the research consortium and the process of collecting and checking the data as well as the production of reports for participating schools; we are grateful to Dawn Pollard, Daryl Brown and Sam Smith for overseeing that. -

Henrik Steffens

Henrik Steffens (1779 bis 1845) als Lehrer der Mineralogie und Geologie an der Universität Halle und sein Ausscheiden aus dieser Lehranstall1 Von Walter Steiner Mit 8 Abbildungen (Eingegangen am 17. Juli 1969) An der halleschen Universität haben seit ihrer Gründung im Jahre 1694 natur kundliche Fragen, und speziell geologische und mineralogische, stets eine Rolle ge spielt. Anfangs waren es vornehmlich Mediziner, wie Friedrich Hoffmann (1616 bis 1742)" und der flei.fjig sammelnde Johann Friedrich Gottlieb Goldhagen (1742 bis 1788)" - die sich mineralogischer Beschäftigung rühmen konnten. Aber schon 1780 trug eine Persönlichkeit an der halleschen Universität den Titel eines .Professors 4 philosophiae ordinario und Specie der Naturgeschichte und Mineralogie" • Es war der Weltumsegler Johann Reinhold Forster (1729 -1798)5, der einen 1 Zum 125. Todestag von H. Steffens im Jahre 1970. 2 Friedrich Hoffmann (1616-1742). Von 1693-1742 Professorprimarius für Medizin an der Universität Halle. Hielt Vorlesungen über Anatomie, Chirurgie, praktische Medizin. Physik und Chemie. Besitzer eines Naturalienkabinetts. Sehr bekannt geworden durch die nach ihm benannten Hoffmanns-Tropfen und die Erschlie(jung der Lauchstädter Heil quellen. 3 Johann Friedrich Gottlieb Goldhagen (1742-1788) . 1769 zum Professor Philosophiae et Historia naturalis ordinarius ernannt; damit erstmals eine naturkundliche Professur an der philosoph. Fakultät. Er lit!st u. a. Naturgeschichte, Mineralogie und Lithologie. Be sitzer eines bedeutenden Naturalienkabinetts, das zum Grundstein sowohl der mineralo gisch-geologischen als auch der zoologischen Universitätssammlung wurde. 1788 stirbt er im 46. Lebensjahr an Typhus (s. Kaiser, W. & Krosch, K. H.: Zur Geschichte der Medi zinischen Fakultät der Universität Halle im 18. Jahrhundert: Johann Friedrich Gottlieb Goldhagen (1742-1788) und Friedrich Albert Kar! Gren (1760-1798) . -

Essays on Scandinavian Literature

Essays On Scandinavian Literature By Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen Essays On Scandinavian Literature BJÖRNSTJERNE BJÖRNSON I Björnstjerne Björnson is the first Norwegian poet who can in any sense be called national. The national genius, with its limitations as well as its virtues, has found its living embodiment in him. Whenever he opens his mouth it is as if the nation itself were speaking. If he writes a little song, hardly a year elapses before its phrases have passed into the common speech of the people; composers compete for the honor of interpreting it in simple, Norse-sounding melodies, which gradually work their way from the drawing-room to the kitchen, the street, and thence out over the wide fields and highlands of Norway. His tales, romances, and dramas express collectively the supreme result of the nation's experience, so that no one to- day can view Norwegian life or Norwegian history except through their medium. The bitterest opponent of the poet (for like every strong personality he has many enemies) is thus no less his debtor than his warmest admirer. His speech has stamped itself upon the very language and given it a new ring, a deeper resonance. His thought fills the air, and has become the unconscious property of all who have grown to manhood and womanhood since the day when his titanic form first loomed up on the horizon of the North. It is not only as their first and greatest poet that the Norsemen love and hate him, but also as a civilizer in the widest sense. But like Kadmus, in Greek myth, he has not only brought with him letters, but also the dragon-teeth of strife, which it is to be hoped will not sprout forth in armed men. -

Kierkegaard and the Limits of Thought

1 Kierkegaard and the Limits of Thought Daniel Watts Whereof we cannot speak, thereof we have just contradicted ourselves. (Graham Priest) The ultimate can be reached only as limit. (Søren Kierkegaard) Graham Priest’s Beyond the Limits of Thought (Priest 2001) parades an eclectic line-up of thinkers to show how the history of philosophy has been shaped by the spectre of paradoxes at the limits of thought. One name that is missing from Priest’s line-up is ‘Søren Kierkegaard’. This omission is something of a surprise, especially given Hegel’s centrality in the book and its (second- edition) inclusion of Heidegger and Derrida. For, Kierkegaard’s writings are famous for nothing if not the way they involve such notions as ‘the absurd’, ‘the incomprehensible’ and ‘the Absolute Paradox’ and for their opposition to Hegelian ‘mediation’. But one can appreciate why an author might hesitate to venture something pithy about Kierkegaard on the limits of thought. For one thing, there is a real question whether we are supposed to take at all seriously talk of ‘the Absolute Paradox’ and the like in his enigmatic and often playful texts. And, as we shall see, the critics are so far from consensus in this regard as to associate Kierkegaard with nearly every imaginable view. I hope in this essay to help illuminate Kierkegaard’s place in the history of thinking about the limits of thought. I shall concentrate in the first instance on his treatment of the idea that 2 Christianity cannot be thought or understood. I shall begin by showing how this idea is ostensibly advanced by the pseudonymous work, Philosophical Fragments; and how this text positively courts the threat of self-referential incoherence in this connection. -

A Comparison of Students' Interest in STEM Across Science Standard

1 A COMPARISON OF STUDENTS’ INTEREST IN STEM ACROSS SCIENCE STANDARD TYPES by Brienne Kylie May Liberty University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University 2021 2 A COMPARISON OF STUDENTS’ INTEREST IN STEM ACROSS SCIENCE STANDARD TYPES by Brienne Kylie May A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA 2021 APPROVED BY: Jillian L. Wendt, Ed.D., Committee Chair and Methodologist Michelle Barthlow, Ed.D., Committee Member 3 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my biggest cheerleader, my husband Steve, who never let me lose sight of my goal and to my daughter, Fiana, who was born right in the middle of my doctoral journey and held the position of my greatest motivator from day one. 4 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my dissertation chair, Dr. Jillian Wendt for her patience, feedback, and endless encouragement and my committee member Dr. Michelle Barthlow for her guidance and expertise. I would also like to thank the students, teachers, principals, and superintendents who contributed to my data collection during a very difficult school year. 5 Abstract The purpose of this study is to determine whether students enrolled in ninth and 10th grade science classes implementing the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) have significantly different interests in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) compared to students enrolled in classes structured around alternate state standards unrelated to the NGSS. The study also investigates how such interests may differ among genders. No research has been conducted to date to determine the potential effects of the NGSS on student interest in STEM or whether these standards impact student interest at all.