Nr 8 / 2016 Nr 8 / 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnomusicologie Et Anthropologie De La Musique: Une Question De Perspective » Anthropologie Et Sociétés, Vol

Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie Anciennement Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles 28 | 2015 Le goût musical Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/2484 ISSN : 2235-7688 Éditeur ADEM - Ateliers d’ethnomusicologie Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 novembre 2015 ISBN : 978-2-88474-373-0 ISSN : 1662-372X Référence électronique Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie, 28 | 2015, « Le goût musical » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 15 novembre 2017, consulté le 06 mai 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/2484 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 6 mai 2019. Article L.111-1 du Code de la propriété intellectuelle. 1 L’étude du goût musical a rarement été appliquée aux musiques de tradition orale. Ce numéro aborde cette question non pas sous l’angle philosophique ou sociologique, mais d’un point de vue spécifiquement ethnomusicologique. Il s’agit de montrer comment des musiciens de sociétés variées, expriment et manifestent leurs goûts sur la musique qu’ils pratiquent, en fonction de leurs champs d’expérience. À partir de l’hypothèse qu’il existe partout une conception du « bien chanter » et du « bien jouer » qui sous-tend les divers savoir-faire musicaux, ce volume aborde les critères du goût musical selon plusieurs méthodes, notamment par l’analyse du vocabulaire des jugements de goût et celle des modalités d’exécution, le tout en relation aux contextes et aux systèmes de pensée locaux. Ce dossier s’attache ainsi à décrire les conceptions vernaculaires du goût musical afin d’explorer le champ -

Ethnomusicology a Very Short Introduction

ETHNOMUSICOLOGY A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION Thimoty Rice Sumário Chapter 1 – Defining ethnomusicology...........................................................................................4 Ethnos..........................................................................................................................................5 Mousikē.......................................................................................................................................5 Logos...........................................................................................................................................7 Chapter 2 A bit of history.................................................................................................................9 Ancient and medieval precursors................................................................................................9 Exploration and enlightenment.................................................................................................10 Nationalism, musical folklore, and ethnology..........................................................................10 Early ethnomusicology.............................................................................................................13 “Mature” ethnomusicology.......................................................................................................15 Chapter 3........................................................................................................................................17 Conducting -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

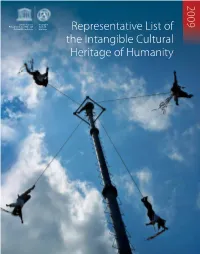

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Of

RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 2 2009 United Nations Intangible Educational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 5 Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 1 2009 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 2 © UNESCO/Michel Ravassard Foreword by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO UNESCO is proud to launch this much-awaited series of publications devoted to three key components of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The publication of these first three books attests to the fact that the 2003 Convention has now reached the crucial operational phase. The successful implementation of this ground-breaking legal instrument remains one of UNESCO’s priority actions, and one to which I am firmly committed. In 2008, before my election as Director-General of UNESCO, I had the privilege of chairing one of the sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in Sofia, Bulgaria. This enriching experience reinforced my personal convictions regarding the significance of intangible cultural heritage, its fragility, and the urgent need to safeguard it for future generations. Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 3 It is most encouraging to note that since the adoption of the Convention in 2003, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has become more familiar thanks largely to the efforts of UNESCO and its partners worldwide. -

GOO-80-02119 392P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 228 863 FL 013 634 AUTHOR Hatfield, Deborah H.; And Others TITLE A Survey of Materials for the Study of theUncommonly Taught Languages: Supplement, 1976-1981. INSTITUTION Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, D.C.Div. of International Education. PUB DATE Jul 82 CONTRACT GOO-79-03415; GOO-80-02119 NOTE 392p.; For related documents, see ED 130 537-538, ED 132 833-835, ED 132 860, and ED 166 949-950. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Dictionaries; *InStructional Materials; Postsecondary Edtmation; *Second Language Instruction; Textbooks; *Uncommonly Taught Languages ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography is a supplement tothe previous survey published in 1976. It coverslanguages and language groups in the following divisions:(1) Western Europe/Pidgins and Creoles (European-based); (2) Eastern Europeand the Soviet Union; (3) the Middle East and North Africa; (4) SouthAsia;(5) Eastern Asia; (6) Sub-Saharan Africa; (7) SoutheastAsia and the Pacific; and (8) North, Central, and South Anerica. The primaryemphasis of the bibliography is on materials for the use of theadult learner whose native language is English. Under each languageheading, the items are arranged as follows:teaching materials, readers, grammars, and dictionaries. The annotations are descriptive.Whenever possible, each entry contains standardbibliographical information, including notations about reprints and accompanyingtapes/records -

MUS 360 Music in the Global Environment Instructor: Dr. Aaron I

MUS 360 Music in the Global Environment Instructor: Dr. Aaron I. Hilbun Office Location: 223 Keene Hall Office Hours: by appointment only Office Phone: (407) 691 1126 Email: [email protected] Course Objectives: Be able to identify cultures and countries from around the world. Be able to identify and classify musical instruments and genres. Be able to identify how music is used in different societies. Have a basic understanding of the development of music in different cultures. Be able to recognize and identify the cultural values of diverse musical traditions. Understand how music is linked to spirituality, politics, class and identity in other cultures. Learn appropriate ethnomusicological terminology for analyzing and describing music within social and cultural contexts. Understand how globalization affects music. Required Materials: Terry E. Miller and Andrew Shahriari, World Music: A Global Journey Reserve Readings: Catherine Ellis, Aboriginal Music: Education for Living Helen Myers, Ethnomusicology: Historical and Regional Studies Bruno Nettl, Excursions in World Music Michael Tenzer, Balinese Music Traditional Korean Music Chris McGowan and Ricardo Pessanha, The Brazilian Sound Articles from scholarly journals and newspapers as assigned Grading: Midterm Exam 20% Research project and presentation 25% Concert reports (2 at 10% each) 20% Participation in class discussion 10% Final Exam 25% Exams: A midterm exam will be given approximately halfway through the semester. The midterm will assess both your written and aural work, and will consist of multiple choice, matching and true or false questions. The final exam will be similar in nature to the midterm, except that it is comprehensive and will include material from the entire semester. -

Society for Ethnomusicology 59Th Annual Meeting, 2014 Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology 59th Annual Meeting, 2014 Abstracts Young Tradition Bearers: The Transmission of Liturgical Chant at an then forms a prism through which to rethink the dialectics of the amateur in Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church in Seattle music-making in general. If 'the amateur' is ambiguous and contested, I argue David Aarons, University of Washington that State sponsorship is also paradoxical. Does it indeed function here as a 'redemption of the mundane' (Biancorosso 2004), a societal-level positioning “My children know it better than me,” says a first generation immigrant at the gesture validating the musical tastes and moral unassailability of baby- Holy Trinity Eritrean Orthodox Church in Seattle. This statement reflects a boomer retirees? Or is support for amateur practice merely self-interested, phenomenon among Eritrean immigrants in Seattle, whereby second and fails to fully counteract other matrices of value-formation, thereby also generation youth are taught ancient liturgical melodies and texts that their limiting potentially empowering impacts in economies of musical and symbolic parents never learned in Eritrea due to socio-political unrest. The liturgy is capital? chanted entirely in Ge'ez, an ecclesiastical language and an ancient musical mode, one difficult to learn and perform, yet its proper rendering is pivotal to Emotion and Temporality in WWII Musical Commemorations in the integrity of the worship (Shelemay, Jeffery, Monson, 1993). Building on Kazakhstan Shelemay's (2009) study of Ethiopian immigrants in the U.S. and the Margarethe Adams, Stony Brook University transmission of liturgical chant, I focus on a Seattle Eritrean community whose traditions, though rooted in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, are The social and felt experience of time informs the way we construct and affected by Eritrea's turbulent history with Ethiopia. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity As Heritage Fund

ElemeNts iNsCriBed iN 2012 oN the UrGeNt saFeguarding List, the represeNtatiVe List iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL HERITAGe aNd the reGister oF Best saFeguarding praCtiCes What is it? UNESCo’s ROLe iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL SECRETARIAT Intangible cultural heritage includes practices, representations, Since its adoption by the 32nd session of the General Conference in HERITAGe FUNd oF THE CoNVeNTION expressions, knowledge and know-how that communities recognize 2003, the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural The Fund for the Safeguarding of the The List of elements of intangible cultural as part of their cultural heritage. Passed down from generation to Heritage has experienced an extremely rapid ratification, with over Intangible Cultural Heritage can contribute heritage is updated every year by the generation, it is constantly recreated by communities in response to 150 States Parties in the less than 10 years of its existence. In line with financially and technically to State Intangible Cultural Heritage Section. their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, the Convention’s primary objective – to safeguard intangible cultural safeguarding measures. If you would like If you would like to receive more information to participate, please send a contribution. about the 2003 Convention for the providing them with a sense of identity and continuity. heritage – the UNESCO Secretariat has devised a global capacity- Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural building strategy that helps states worldwide, first, to create -

Decisions Paris, 7 December 2012 Original: English/French

7 COM ITH/12/7.COM/Decisions Paris, 7 December 2012 Original: English/French CONVENTION FOR THE SAFEGUARDING OF THE INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE INTERGOVERNMENTAL COMMITTEE FOR THE SAFEGUARDING OF THE INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE Seventh session UNESCO Headquarters, Paris 3 to 7 December 2012 DECISIONS ITH/12/7.COM/Decisions – page 2 DECISION 7.COM 2 The Committee, 1. Having examined document ITH/12/7.COM/2 Rev., 2. Adopts the agenda of its seventh session as annexed to this Decision. Agenda of the seventh session of the Committee 1. Opening of the session 2. Adoption of the agenda of the seventh session of the Committee 3. Replacement of the rapporteur 4. Admission of observers 5. Adoption of the summary records of the sixth ordinary session and fourth extraordinary session of the Committee 6. Examination of the reports of States Parties on the implementation of the Convention and on the current status of elements inscribed on the Representative List 7. Report of the Consultative Body on its work in 2012 8. Examination of nominations for inscription in 2012 on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding 9. Examination of proposals for selection in 2012 to the Register of Best Safeguarding Practices 10. Examination of International Assistance requests greater than US$25,000 11. Report of the Subsidiary Body on its work in 2012 and examination of nominations for inscription in 2012 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity 12. Questions concerning the 2013, 2014 and 2015 examination cycles a. System of rotation for the members of the Consultative Body b. -

BORN, Western Music

Western Music and Its Others Western Music and Its Others Difference, Representation, and Appropriation in Music EDITED BY Georgina Born and David Hesmondhalgh UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London All musical examples in this book are transcriptions by the authors of the individual chapters, unless otherwise stated in the chapters. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2000 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Western music and its others : difference, representation, and appropriation in music / edited by Georgina Born and David Hesmondhalgh. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-520-22083-8 (cloth : alk. paper)—isbn 0-520--22084-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Music—20th century—Social aspects. I. Born, Georgina. II. Hesmondhalgh, David. ml3795.w45 2000 781.6—dc21 00-029871 Manufactured in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 10987654321 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). 8 For Clara and Theo (GB) and Rosa and Joe (DH) And in loving memory of George Mully (1925–1999) CONTENTS acknowledgments /ix Introduction: On Difference, Representation, and Appropriation in Music /1 I. Postcolonial Analysis and Music Studies David Hesmondhalgh and Georgina Born / 3 II. Musical Modernism, Postmodernism, and Others Georgina Born / 12 III. Othering, Hybridity, and Fusion in Transnational Popular Musics David Hesmondhalgh and Georgina Born / 21 IV. Music and the Representation/Articulation of Sociocultural Identities Georgina Born / 31 V. -

Musical Practices in the Balkans: Ethnomusicological Perspectives

MUSICAL PRACTICES IN THE BALKANS: ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES МУЗИЧКЕ ПРАКСЕ БАЛКАНА: ЕТНОМУЗИКОЛОШКЕ ПЕРСПЕКТИВЕ СРПСКА АКАДЕМИЈА НАУКА И УМЕТНОСТИ НАУЧНИ СКУПОВИ Књига CXLII ОДЕЉЕЊЕ ЛИКОВНЕ И МУЗИЧКЕ УМЕТНОСТИ Књига 8 МУЗИЧКЕ ПРАКСЕ БАЛКАНА: ЕТНОМУЗИКОЛОШКЕ ПЕРСПЕКТИВЕ ЗБОРНИК РАДОВА СА НАУЧНОГ СКУПА ОДРЖАНОГ ОД 23. ДО 25. НОВЕМБРА 2011. Примљено на X скупу Одељења ликовне и музичке уметности од 14. 12. 2012, на основу реферата академикâ Дејана Деспића и Александра Ломе У р е д н и ц и Академик ДЕЈАН ДЕСПИЋ др ЈЕЛЕНА ЈОВАНОВИЋ др ДАНКА ЛАЈИЋ-МИХАЈЛОВИЋ БЕОГРАД 2012 МУЗИКОЛОШКИ ИНСТИТУТ САНУ SERBIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS ACADEMIC CONFERENCES Volume CXLII DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS AND MUSIC Book 8 MUSICAL PRACTICES IN THE BALKANS: ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE HELD FROM NOVEMBER 23 TO 25, 2011 Accepted at the X meeting of the Department of Fine Arts and Music of 14.12.2012., on the basis of the review presented by Academicians Dejan Despić and Aleksandar Loma E d i t o r s Academician DEJAN DESPIĆ JELENA JOVANOVIĆ, PhD DANKA LAJIĆ-MIHAJLOVIĆ, PhD BELGRADE 2012 INSTITUTE OF MUSICOLOGY Издају Published by Српска академија наука и уметности Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts и and Музиколошки институт САНУ Institute of Musicology SASA Лектор за енглески језик Proof-reader for English Јелена Симоновић-Шиф Jelena Simonović-Schiff Припрема аудио прилога Audio examples prepared by Зоран Јерковић Zoran Jerković Припрема видео прилога Video examples prepared by Милош Рашић Милош Рашић Технички -

Consolidated List of Abstracts (AAWM

ABSTRACTS Keynote Addresses Music Analysis and Ethnomusicology: some reflections on rhythmic theory Martin Clayton Durham University, UK If these are interesting times for the relationship between ethnomusicology and music analysis, then this is particularly true in the area of rhythmic and metrical theory. On the one hand, time seems to be more amenable than many other dimensions of music to cross-cultural comparison; indeed, recent work in the (traditionally Western-art-music focused) discipline of ‘music theory’ develops a set of concepts that appear to be generalizable across a wide array of musical traditions. At the same time, ethnomusicology’s history of theorising rhythm, especially in Africa, has acted as a lightning rod for heated criticism of the discipline. Ethnomusicology’s relationship to rhythmic theory appears to be at the same time full of potential and deeply problematic. In this paper I will reflect on some of the issues raised by theorising and analysing musical time cross- culturally, both now and in the past. What principles allow us to continue to develop general theories of rhythm and metre, and what – apart from reflecting on the enormous diversity of musical practice and theory around the world – does a historically self-aware ethnomusicology have to offer that project? Music, Identity Politics, and the Clever Boy from Croydon Nicholas Cook University of Cambridge, UK Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912)—in Elgar’s equivocal term the ‘clever boy’ from Croydon— was discovered by the Royal College of Music set at an early age, and his Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, completed when the composer was 23, was one of the great commercial successes of its time.