Consolidated List of Abstracts (AAWM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof. Wang, Yaohua Fujian Normal University, China Intangible cultural heritage is the memory of human historical culture, the root of human culture, the ‘energic origin’ of the spirit of human culture and the footstone for the construction of modern human civilization. Ever since China joined the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004, it has done a lot not only on cognition but also on action to contribute to the protection and transmission of intangible cultural heritage. Please allow me to expatiate these on the case of Chinese nanyin(南音, southern music). I. The precious multi-values of nanyin decide the necessity of protection and transmission for Chinese nanyin. Nanyin, also known as “nanqu” (南曲), “nanyue” (南乐), “nanguan” (南管), “xianguan” (弦管), is one of the oldest music genres with strong local characteristics. As major musical genre, it prevails in the south of Fujian – both in the cities and countryside of Quanzhou, Xiamen, Zhangzhou – and is also quite popular in Taiwan, Hongkong, Macao and the countries of Southeast Asia inhabited by Chinese immigrants from South Fujian. The music of nanyin is also found in various Fujian local operas such as Liyuan Opera (梨园戏), Gaojia Opera (高甲戏), line-leading puppet show (提线木偶戏), Dacheng Opera (打城戏) and the like, forming an essential part of their vocal melodies and instrumental music. As the intangible cultural heritage, nanyin has such values as follows. I.I. Academic value and historical value Nanyin enjoys a reputation as “a living fossil of the ancient music”, as we can trace its relevance to and inheritance of Chinese ancient music in terms of their musical phenomena and features of musical form. -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

A Japanese Tradition I Want to Share

A Japanese Tradition I Want To Share Sekioka Maika Hiroshima Prefectural Miyoshi High School The charm of the Sanshin is that it heals and soothes. The Sanshin has been loved in Okinawa for a long time. Nowadays, it is used for celebrations and festivals. The beautiful sound makes you feel nostalgic and gives a sense of security. So, I think the Sanshin is loved not only in Okinawa but also in Japan and around the world. The Sanshin was introduced to Japan from Mainland China in the 14th century. It has been improved over the years to become the present form. It was not a major instrument back then because it was expensive. However, some people made an instrument that imitates the Sanshin, out of cheap materials. After that, it became popular in the whole Okinawa area. That was the beginning of when the Sanshin became a traditional instrument in Okinawa. During World War Ⅱ, only Okinawa experienced ground combat. Many people were injured and killed. At that time, the Sanshin healed the hearts of the Okinawan residents. However, it was difficult for people to get the Sanshin, so they made it out of wood and empty cans. That was called the “Kankara Sanshin.” The Sanshin has been played for a hundred years. Thus, the Sanshin is more special than other instruments for Okinawans. I took a Sanshin class last year. I studied the history of the Sanshin, how to play it, and learned how it differs from the Shamisen. Before that, I did not know the difference between the Sanshin and Shamisen because their shapes are similar. -

Ethnomusicology a Very Short Introduction

ETHNOMUSICOLOGY A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION Thimoty Rice Sumário Chapter 1 – Defining ethnomusicology...........................................................................................4 Ethnos..........................................................................................................................................5 Mousikē.......................................................................................................................................5 Logos...........................................................................................................................................7 Chapter 2 A bit of history.................................................................................................................9 Ancient and medieval precursors................................................................................................9 Exploration and enlightenment.................................................................................................10 Nationalism, musical folklore, and ethnology..........................................................................10 Early ethnomusicology.............................................................................................................13 “Mature” ethnomusicology.......................................................................................................15 Chapter 3........................................................................................................................................17 Conducting -

'Ukulele Musical,' Recent Forays Into World Music

imply put, Daniel Ho is one of the Music Album, Pop Instrumental Album, and most prolific and successful musi- (now-defunct) Hawaiian Music Album cate- cians Hawaii has ever produced. Born gories. He has also been a multiple winner at and raised on Oahu, he has spent most of his the Na Hoku Hanohano and Hawaii Music adult years living in the Los Angeles area, Awards (for everything from Studio Musician but the Islands have always exerted a strong of the Year to trophies for Inspirational/Gos- influence on his creative life, even when he pel Album, Slack Key Album, Folk Album, wasn’t playing explicitly Hawaiian music. New Age Album, even Best Liner Notes!), and Consider this seriously abridged recitation also at Taiwan’s Golden Melody Awards. He’s of some of his career highlights: written and published 14 music and instruc- In his early 20s, after studying music the- tional books, performed with the Honolulu ory and composition at the Grove School of Symphony, and toured the world as a solo Music in L.A. and then at the University of artist. Hawaii on Oahu, the gifted multi-instrumen- The past few years have been remarkably talist—he had already studied organ, ukulele, productive for this tireless artist: There are classical guitar, and classical piano by the his instrumental, production, composition, time he started high school—became a song- and arrangement contributions to a pair of writer/arranger and then keyboard player extraordinary discs featuring music and for the popular L.A.-based commercial jazz players from Mongolia (2017’s Between Sky & band Kilauea, a fixture on the contemporary Prairie) and China (the 2019 release Embroi- jazz charts through much of the 1990s. -

Shizuko Akamine and the So-Shin Kai: Perpetuating an Okinawan Music Tradition in a Multi-Ethnic Community

SHIZUKO AKAMINE AND THE SO-SHIN KAI: PERPETUATING AN OKINAWAN MUSIC TRADITION IN A MULTI-ETHNIC COMMUNITY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MUSIC DECEMBER 2018 By Darin T. Miyashiro Thesis Committee: Ricardo D. Trimillos, Chairperson Frederick Lau Christine R. Yano ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank, first and foremost, the thesis committee, Dr. Christine Yano, Dr. Frederick Lau, and especially the chairperson Dr. Ricardo Trimillos, for their patience in accepting this long overdue manuscript. Dr. Trimillos deserves extra thanks for initiating this project which began by assisting the author and the thesis subject, Shizuko Akamine, in receiving the Hawai‘i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts Folk & Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Grant with support from Arts Program Specialist Denise Miyahana. Special thanks to Prof. Emeritus Barbara B. Smith and the late Prof. Dr. Robert Günther for their support in helping the author enter the ethnomusicology program. The author would also like to thank the music department graduate studies chair Dr. Katherine McQuiston for her encouragement to follow through, and for scheduling extremely helpful writing sessions where a large part of this thesis was written. This thesis has taken so many years to complete there are far too many supporters (scholarship donors, professors, classmates, students, family, friends, etc.) to thank here, but deep appreciation goes out to each and every one, most of all to wife Mika for being too kind and too patient. Finally, the author would like to thank the late Shizuko Akamine for being the inspiration for this study and for generously sharing so much priceless information. -

Japan in the Meiji

en Japan in the Meiji Era The collection of Heinrich von Siebold Galleries of Marvel Japan in the Meiji Era Japan in the Meiji Era The collection of The collection of Heinrich von Siebold Heinrich von Siebold This exhibition grew out of a research Meiji period (1868–1912) as a youth. Through project of the Weltmuseum Wien in the mediation of his elder brother Alexan- co-operation with the research team of der (1846–1911), he obtained a position as the National Museum of Japanese History, interpreter to the Austro-Hungarian Diplo- Sakura, Japan. It is an attempt at a reap- matic Mission in Tokyo and lived in Japan praisal of nineteenth-century collections for most of his life, where he amassed a of Japanese artefacts situated outside of collection of more than 20,000 artefacts. He Japan. The focus of this research lies on donated about 5,000 cultural objects and Heinrich von Siebold (1852–1908), son of art works to Kaiser Franz Joseph in 1889. the physician and author of numeral books About 90 per cent of the items pictured in Hochparterre on Japan Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796– the photographs in the exhibition belong to 1866). Heinrich went to Japan during the the Weltmuseum Wien. Room 1 Ceramics and agricultural implements Room 2 Weapons and ornate lacquer boxes Room 3 Musical instruments and bronze vessels Ceramics and Room 1 agricultural implements 1 The photographs show a presentation of artefacts of the Ainu from Hokkaido, togeth- This large jar with a lid is Kutani ware from dynasty (1638–1644) Jingdezhen kilns, part of Heinrich von Siebold’s collection from er with agricultural and fishing implements Ishikawa prefecture. -

Resources for Learning How to Read Torah and Haftara at Shearith Israel

Resources for learning how to read Torah and Haftara at Shearith Israel Chumashim and Tikkunim: Etz Hayim: Torah and Commentary. ISBN 9780827607125. Available from www.rabbinicalassembly.org and other vendors. Etz Hayim: Torah and Commentary Travel Edition. ISBN 9780827608047. Available from www.rabbinicalassembly.org and other vendors. The JPS Tanakh. Jewish Publication Society (JPS), Philadelphia. Many editions and formats in Hebrew, and Hebrew/English. https://jps.org/resources/tanakh-customer-guide/ The Koren Tanakh, and The Koren Chumash. Koren Publishers, Jerusalem. Many editions and formats in Hebrew, Hebrew/English, and with other languages. www.korenpub.com The Koren Tikkun Kor'im. Koren Publishers, Jerusalem. ISBN 978-9653010574. Several editions and formats. www.korenpub.com The Kestenbaum Edition Tikkun. Artscroll publishers. ISBN 9781578193134. Several editions. Artscroll.com. Tikkun Torah Lakorim, ed. Asher Scharfstein. Ktav Publishing House. ISBN: 978-0870685484 1969 classic; priced well; less bulky than most. www.ktav.com and other vendors. Tikun Korim -Simanim (Nusach Ashkenaz). Nehora.com. Your best resource: Our CSI members. The Religious Life Committee and experienced ba’alim keria in our shul want to help you learn, and are available for tutoring, answering questions, giving feedback, or teaching classes. Andrea Seidel Slomka ([email protected]) is a great first point of contact. Websites with audio files intended for self-learning for ba’alei keriah and haftarah readers in Ashkenazi nusach: http://bible.ort.org/intro1.asp?lang=1 Navigating the Bible II software published by World ORT shows chumash and Torah text and gives recordings of each sentence. It can be used online without cost, or they say you can buy the software on CD. -

Performing Okinawan

PERFORMING OKINAWAN: BRIDGING CULTURES THROUGH MUSIC IN A DIASPORIC SETTING A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES MAY 2014 By Lynette K. Teruya Thesis Committee: Christine R. Yano, Chairperson Gay M. Satsuma Joyce N. Chinen Keywords: Okinawans in Hawai‘i, diasporic studies, identity, music, performance © Copyright 2014 by Lynette K. Teruya All Rights Reserved i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Okage sama de, ukaji deebiru, it is thanks to you… It has taken many long years to reach this point of completion. I could not have done this project alone and my heart is filled with much gratitude as I acknowledge those who have helped me through this process. I would like to thank my thesis committee -- Drs. Christine Yano, Gay Satsuma, and Joyce Chinen -- for their time, patience, support and encouragement to help me through this project. Finishing this thesis while holding down my full-time job was a major challenge for me and I sincerely appreciate their understanding and flexibility. My thesis chair, Dr. Yano, spent numerous hours reviewing my drafts and often gave me helpful feedback to effectively do my revisions. I would also like to thank my sensei, Katsumi Shinsato, his family, and fellow members of the Shinsato Shosei Kai; without their cooperation and support, this particular thesis could not have been done. I would also like to thank Mr. Ronald Miyashiro, who produces the Hawaii Okinawa Today videos, for generously providing me with a copy of the Hawaii United Okinawa Association’s Legacy Award segment on Katsumi Shinsato; it was a valuable resource for my thesis. -

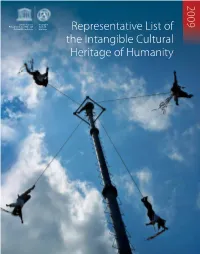

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Of

RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 2 2009 United Nations Intangible Educational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 5 Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 1 2009 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 2 © UNESCO/Michel Ravassard Foreword by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO UNESCO is proud to launch this much-awaited series of publications devoted to three key components of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The publication of these first three books attests to the fact that the 2003 Convention has now reached the crucial operational phase. The successful implementation of this ground-breaking legal instrument remains one of UNESCO’s priority actions, and one to which I am firmly committed. In 2008, before my election as Director-General of UNESCO, I had the privilege of chairing one of the sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in Sofia, Bulgaria. This enriching experience reinforced my personal convictions regarding the significance of intangible cultural heritage, its fragility, and the urgent need to safeguard it for future generations. Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 3 It is most encouraging to note that since the adoption of the Convention in 2003, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has become more familiar thanks largely to the efforts of UNESCO and its partners worldwide. -

“Defining My Jewish Identity”

27th Annual TORATHON2016 “Defining My Jewish Identity” Once again this year, Torathon will begin with a joyous one hour concert starting at 6pm. Sit back and enjoy as a cadre of noted Jewish cantors and musicians led by Ellen Allard share the stories and music that helped shape their own Jewish identity. Following the concert, our wonderful evening of learning will begin. From 7pm to 10pm you can choose from 25 one hour classes, lectures, discussions, and workshops led by the region’s distinguished rabbis, cantors, Jewish edu- cators, Jewish community and organizational leaders. A dessert reception and social hour will close the evening. Saturday, November 12, 2016 5:15 P.M. – 10:00 P.M. Registration begins Refreshments to follow. CONGREGATION BETH ISRAEL 15 Jamesbury Drive, Worcester, MA Purchase Torathon tickets Sponsored by and view classes online at jewishcentralmass.org/torathon 27th Annual ALEPH 7:10 PM – 8:00 PM A1 THIS WEEK’S ELECTION RESULTS: GOOD FOR THE JEWS? ISRAEL? Join us in analyzing the results of this past week’s elections in the House and Senate. Democrats? Republicans? Independents? How will the new president and the new com- TORATHON position of the Congress affect the interests of Israel and the American-Israel alliance? JACK GOLDBERG, Area Director for AIPAC (The American-Israel Public Affairs 2016 Committee) ONGOING from 5:15PM A2 HOW THE MUSIC OF DEBBIE FRIEDMAN MADE ME THE RABBI I AM TODAY My journey into the Rabbinate began with Jewish music, specifically the inspiration of Registration Debbie Friedman z”l. Through personal biography and song, we’ll go on a journey with a particular focus on the music and spirit that Debbie brought to thousands through her healing services. -

The Journal the Music Academy

Golden Jubilee Special Number THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Voi. x lv iii 1977 31? TElfa TfM 3 I msife w*? ii ■“ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins nor in the Sun; (but) where my bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada! ” Edited by T, S. PARTHASARATHY 1980 The Music Academy Madras 306, Mowbray’s Road, Madras - 600 014 Annual Subscription - Rs, 12; Foreign $ 3.00 Golden Jubilee Special Number THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. XLVIII 1977 TOlfil 51 ^ I to qprfo to fogifa urc? u ** I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins nor in the Snn; (ftK| fheiV my bhaktas sirig, there fa I, NaradS f ** Edited by TiS. PARTHASARATHY 1980 The Musitf Academy Madras 366, Mowbray’s Road, Madras - 600 014 Annual Subscription - Rs. 12; Foreign $ 3.00 From Vol. XLVII onwards, this Journal is being published as an Annual. All corresnojd?nc£ sh ^ l^ ^ addressed ^ri T. S. Partha- sarathy, Editor* journal of the Music Academy, Madras-600014. Articles on subjects o f music and dance are accepted for publioation on the understanding that they are contributed solely to *he |*Wf M&P' All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably type written (double-spaced on one side o f the paper only) and should be |^gn|d by the y^iter (giving bis address jn fpll). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views ^expressed by individual contributors.