Evolutionary Trends in the Behaviour and Morphology of the Anatidae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild Patagonia & Central Chile

WILD PATAGONIA & CENTRAL CHILE: PUMAS, PENGUINS, CONDORS & MORE! NOVEMBER 1–18, 2019 Pumas simply rock! This year we enjoyed 9 different cats! Observing the antics of lovely Amber here and her impressive family of four cubs was certainly the highlight in Torres del Paine National Park — Photo: Andrew Whittaker LEADERS: ANDREW WHITTAKER & FERNANDO DIAZ LIST COMPILED BY: ANDREW WHITTAKER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM Sensational, phenomenal, outstanding Chile—no superlatives can ever adequately describe the amazing wildlife spectacles we enjoyed on this year’s tour to this breathtaking and friendly country! Stupendous world-class scenery abounded with a non-stop array of exciting and easy birding, fantastic endemics, and super mega Patagonian specialties. Also, as I promised from day one, everyone fell in love with Chile’s incredible array of large and colorful tapaculos; we enjoyed stellar views of all of the country’s 8 known species. Always enigmatic and confiding, the cute Chucao Tapaculo is in the Top 5 — Photo: Andrew Whittaker However, the icing on the cake of our tour was not birds but our simply amazing Puma encounters. Yet again we had another series of truly fabulous moments, even beating our previous record of 8 Pumas on the last day when I encountered a further 2 young Pumas on our way out of the park, making it an incredible 9 different Pumas! Our Puma sightings take some beating, as they have stood for the last three years at 6, 7, and 8. For sure none of us will ever forget the magical 45 minutes spent observing Amber meeting up with her four 1- year-old cubs as they joyfully greeted her return. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Sources Cited Alder, L. P. 1963. The calls and displays of African and In Bellrose, F. C. 1976. Ducks, geese and swans of North dian pygmy geese. In Wildfowl Trust, 14th Annual America. 2d ed. Harrisburg, Pa.: Stackpole. Report, pp. 174-75. Bellrose, F. c., & Hawkins, A. S. 1947. Duck weights in Il Ali, S. 1960. The pink-headed duck Rhodonessa caryo linois. Auk 64:422-30. phyllacea (Latham). Wildfowl Trust, 11th Annual Re Bengtson, S. A. 1966a. [Observation on the sexual be port, pp. 55-60. havior of the common scoter, Melanitta nigra, on the Ali, S., & Ripley, D. 1968. Handbook of the birds of India breeding grounds, with special reference to courting and Pakistan, together with those of Nepal, Sikkim, parties.] Var Fagelvarld 25:202-26. -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

Waterbird and Raptor Use of the Arcata Marsh And

WATERBIRD AND RAPTOR USE OF THE ARCATA MARSH AND WILDLIFE SANCTUARY, HUMBOLDT COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, 1984-1986 by J. Mark Higley A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science December 1989 WATERBIRD AND RAPTOR USE OF THE ARCATA MARSH AND WILDLIFE SANCTUARY, HUMBOLDT COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, 1984-1986 by J. Mark Higley Approved by the Master's Thesis Committee Stanley W. Harris, Chairman David W. Kitchen Director, Natural Resources Graduate Program 89/W-180/12/15 Natural Resources Graduate Program Number Approved by the Dean of Graduate Studies Robert Willis ABSTRACT Waterbird use and aquatic vegetation structure of the Arcata Marsh and Wildlife Sanctuary, Humboldt County, California was studied from 9 May 1984 to 21 August 1986. Diurnal waterbird use of each marsh unit was determined by direct counts of all birds on each unit. An average of 2.4 surveys was conducted at high and also at low tide each week. Percent cover of the marsh units was determined by preparing cover maps from low altitude aerial photographs and standing crop biomass was calculated by harvesting samples from random plots. In Gearheart Marsh the coverage of common cattail alpha latifolia) nearly doubled between April 1985 and September 1987 while marsh pennywort (Hydrocotyle ranunculoides) nearly tripled. In September 198 sago pondweed (Potamogeton pectinatus) covered 77.2 percent of Gearheart Marsh. The peak sago pondweed standing crop present in Gearheart Marsh was measured in June 1985 (187.94 grams per square meter ± 113.08 g) and in June 1986 (132.77 grams per square meter ± 88.73 g). -

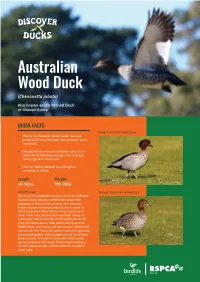

Australian Wood Duck (Chenonetta Jubata)

Australian Wood Duck (Chenonetta jubata) Also known as the ‘Maned Duck’ or ‘Maned Goose’ QUICK FACTS Male Australian Wood Duck • They are nicknamed ‘Maned Goose’ because people think they look more like miniature geese than ducks. • Wood Ducks love heavy rainfall because this is when the tastiest bugs emerge. They also love laying eggs after heavy rain. • They are better adapted to walking than swimming or diving. Length: Weight: 44–50cm 700–955g Identification: Female Australian Wood Duck The Australian Wood Ducks have earnt the nickname ‘Maned Goose’ because of their very goose-like appearance. The feathers around their neck and breast also give the impression of a lion’s mane. In flight, Australian Wood Ducks’ wings come out on show. Their wing tips are black and their wings are a pale grey with a white bar on the underside of the wing. Like many ducks, male and female Australian Wood Ducks vary in size and appearance. Males tend to have a darker head and smaller mane with speckled brown-grey bodies, a black undertail and black lower belly. Females have paler heads with white stripes above and below their eyes. Their breast and flanks are also speckled with a white undertail and white lower belly. BEHAVIOUR DISTRIBUTION & HABITAT Unlike most ducks, Australian Wood Ducks do not favour Australian Wood Ducks are found across most of Australia. swimming and will only enter open water if they’re Flocks of hundreds of birds can be found gathering disturbed. Instead, they prefer to waddle around and graze in southern areas of Australia in autumn and winter. -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

References.Qxd 12/14/2004 10:35 AM Page 771

Ducks_References.qxd 12/14/2004 10:35 AM Page 771 References Aarvak, T. and Øien, I.J. 1994. Dverggås Anser Adams, J.S. 1971. Black Swan at Lake Ellesmere. erythropus—en truet art i Norge. Vår Fuglefauna 17: 70–80. Wildl. Rev. 3: 23–25. Aarvak, T. and Øien, I.J. 2003. Moult and autumn Adams, P.A., Robertson, G.J. and Jones, I.L. 2000. migration of non-breeding Fennoscandian Lesser White- Time-activity budgets of Harlequin Ducks molting in fronted Geese Anser erythropus mapped by satellite the Gannet Islands, Labrador. Condor 102: 703–08. telemetry. Bird Conservation International 13: 213–226. Adrian, W.L., Spraker, T.R. and Davies, R.B. 1978. Aarvak, T., Øien, I.J. and Nagy, S. 1996. The Lesser Epornitics of aspergillosis in Mallards Anas platyrhynchos White-fronted Goose monitoring programme,Ann. Rept. in north central Colorado. J. Wildl. Dis. 14: 212–17. 1996, NOF Rappportserie, No. 7. Norwegian Ornitho- AEWA 2000. Report on the conservation status of logical Society, Klaebu. migratory waterbirds in the agreement area. Technical Series Aarvak, T., Øien, I.J., Syroechkovski Jr., E.E. and No. 1.Wetlands International,Wageningen, Netherlands. Kostadinova, I. 1997. The Lesser White-fronted Goose Afton, A.D. 1983. Male and female strategies for Monitoring Programme.Annual Report 1997. Klæbu, reproduction in Lesser Scaup. Unpubl. Ph.D. thesis. Norwegian Ornithological Society. NOF Raportserie, Univ. North Dakota, Grand Forks, US. Report no. 5-1997. Afton, A.D. 1984. Influence of age and time on Abbott, C.C. 1861. Notes on the birds of the Falkland reproductive performance of female Lesser Scaup. -

Reese--Waterfowl Presentation

Waterfowl – What they are and are not Great variety in sizes, shapes, colors All have webbed feet and bills Sibley reading is great for lots of facts and insights into the group Order Anseriformes Family Anatidae – 154 species worldwide, 44 in NA Subfamily Dendrocygninae – whistling ducks Subfamily Anserinae – geese & swans Subfamily Anatinae - ducks Handout • Indicates those species occurring regularly in ID Ducks = ?? Handout • Indicates those species occurring regularly in ID Ducks = 26 species Geese = ?? Handout • Indicates those species occurring regularly in ID Ducks = 26 species Geese = 6 (3 are rare) Swans = ?? Handout • Indicates those species occurring regularly in ID Ducks = 26 species Geese = 6 Swans = 2 What separates the 3 groups? Ducks - Geese - Swan - What separates the 3 groups? Ducks – smaller, shorter legs & necks Geese – long legs, graze in uplands Swan – shorter legs than geese, long necks, larger size, feed more often in water Non-waterfowl Cranes, rails – beak, rails have lobed feet Coots – bill but lobed feet Grebes – lobed feet Loons – webbed feet but sharp beak Woodcock and snipe – feet not webbed, beaks These are not on handout but are managed by USFWS as are waterfowl On handout: Subfamily Dendrocygninae – whistling ducks – used to be called tree ducks 2 species, more goose-like, longer necks and legs than most ducks, flight is faster than geese, but slower than other ducks Occur along gulf coast and Florida On handout: Subfamily Anserinae – geese and swans Tribe Cygnini – swans – 2 species Tribe Anserini – -

Nesting Biology. Social Patterns and Displays of the Mandarin Duck, a Ix Galericulata

pi)' NESTING BIOLOGY. SOCIAL PATTERNS AND DISPLAYS OF THE MANDARIN DUCK, A_IX GALERICULATA Richard L. Bruggers A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1974 ' __ U J 591913 W A'W .'X55’ ABSTRACT A study of pinioned, free-ranging Mandarin ducks (Aix galericulata) was conducted from 1971-1974 at a 25-acre estate. The purposes 'were to 1) document breeding biology and behaviors, nesting phenology, and time budgets; 2) describe displays associated with copulatory behavior, pair-formation and maintenance, and social encounters; and 3) determine the female's role in male social display and pair formation. The intensive observations (in excess of 400 h) included several full-day and all-night periods. Display patterns were recorded (partially with movies) arid analyzed. The female's role in social display was examined through a series of male and female introductions into yearling and adult male "display parties." Mandarins formed strong seasonal pair bonds, which re-formed in successive years if both individuals lived. Clutches averaged 9.5 eggs and were begun by yearling females earlier and with less fertility (78%) than adult females (90%). Incubation averaged 28-30 days. Duckling development was rapid and sexual dimorphism evident. 9 Adults and yearlings of both sexes could be separated on the basis of primary feather length; females, on secondary feather pigmentation. Mandarin daily activity patterns consisted of repetitious feeding, preening, and loafing, but the duration and patterns of each activity varied with the social periods.