A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coelomic Liposarcoma in an African Pygmy Goose (Nettapus Auritus)

www.symbiosisonline.org Symbiosis www.symbiosisonlinepublishing.com Case Report SOJ Veterinary Sciences Open Access Coelomic Liposarcoma In An African Pygmy Goose (Nettapus Auritus) Jason D Struthers1* and Geoffrey W Pye2 1From the Animal Health Institute, Department of Pathology and Population Medicine, 5725 W. Utopia Rd., Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona 85308, USA. 2Animals, Science, and Environment, Disney’s Animal Kingdom, 1200 N Savannah Circ, Bay Lake, Florida 32830, USA. Received: 25 May, 2018; Accepted: 11 June, 2018; Published: 12 June, 2018 *Corresponding author: : Jason D. Struthers,From the Animal Health Institute, Department of Pathology and Population Medicine, 5725 W. Utopia Rd., Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona 85308, USA. E-mail: [email protected] abutted many tissues, including the ventriculus, kidney, oviduct, Abstract and, most closely, the cloaca. The mass was dissected and isolated A morbid African pygmy goose (Nettapus auritus) developed open- from the surrounding viscera. On section, the mass was greasy, mouth breathing and died during physical exam. Necropsy revealed bacterial salpingitis and a coelomic liposarcoma. Death resulted from (necrosis). The oviduct’s serosa was diffusely grey to light brown a combination of poor body condition, infection, stress of handling, andsoft, wasand markedlymottled tan distended to light red by withsoft tooccasional granular, greygrey firm to brown areas and compromised respiratory and cardiovascular function related to the coelomic liposarcoma. viscid material. A swab of the lumen was submitted for aerobic bacterial culture. Keywords: coelom; duck; liposarcoma; Nettapus auritus; oil red O; pygmy goose Introduction A zoo—born six-year old female African pygmy goose (Nettapus auritus) was found recumbent and lethargic in her enclosure. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

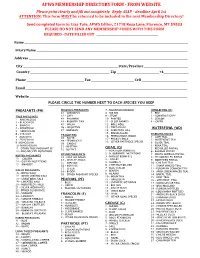

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - from WEBSITE Please Print Clearly and Fill out Completely

APWS MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - FROM WEBSITE Please print clearly and fill out completely. Reply ASAP – deadline April 1st ATTENTION: This form MUST be returned to be included in the next Membership Directory! Send completed form to: Lisa Tate, APWS Editor, 21718 Kesa Lane, Florence, MT 59833 PLEASE DO NOT SEND ANY MEMBERSHIP FUNDS WITH THIS FORM REQUIRED - DATE FILLED OUT ______________________________________________ Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Aviary Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City ________________________________________________________________________ State/Province _________________________________ Country ___________________________________________________________ Zip ________________________________+4___________________ Phone ___________________________________________ Fax ________________________________ Cell __________________________________ Email _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Website ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PLEASE CIRCLE THE NUMBER NEXT TO EACH SPECIES YOU KEEP PHEASANTS (PH) PEACOCK-PHEASANTS 7 - MOUNTAIN BAMBOO JUNGLEFOWL -

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

An Introduction to the Bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes

An introduction to the bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes M.S. Maldonado Fonkén International Mire Conservation Group, Lima, Peru _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY In Peru, the term “bofedales” is used to describe areas of wetland vegetation that may have underlying peat layers. These areas are a key resource for traditional land management at high altitude. Because they retain water in the upper basins of the cordillera, they are important sources of water and forage for domesticated livestock as well as biodiversity hotspots. This article is based on more than six years’ work on bofedales in several regions of Peru. The concept of bofedal is introduced, the typical plant communities are identified and the associated wild mammals, birds and amphibians are described. Also, the most recent studies of peat and carbon storage in bofedales are reviewed. Traditional land use since prehispanic times has involved the management of water and livestock, both of which are essential for maintenance of these ecosystems. The status of bofedales in Peruvian legislation and their representation in natural protected areas and Ramsar sites is outlined. Finally, the main threats to their conservation (overgrazing, peat extraction, mining and development of infrastructure) are identified. KEY WORDS: cushion bog, high-altitude peat; land management; Peru; tropical peatland; wetland _______________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION organic soil or peat and a year-round green appearance which contrasts with the yellow of the The Tropical Andes Cordillera has a complex drier land that surrounds them. This contrast is geography and varied climatic conditions, which especially striking in the xerophytic puna. Bofedales support an enormous heterogeneity of ecosystems are also called “oconales” in several parts of the and high biodiversity (Sagástegui et al. -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

Review of the Ecology, Status and Modelling of Waterbird Populations of the Coorong South Lagoon

Review of the ecology, status and modelling of waterbird populations of the Coorong South Lagoon Thomas A. A. Prowse Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 20/12 www.goyderinstitute.org Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series ISSN: 1839-2725 The Goyder Institute for Water Research is a research alliance between the South Australian Government through the Department for Environment and Water, CSIRO, Flinders University, the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia. The Institute facilitates governments, industries, and leading researchers to collaboratively identify, develop and adopt innovative solutions for complex water management challenges to ensure a sustainable future. This program is part of the Department for Environment and Water’s Healthy Coorong Healthy Basin Program, which is jointly funded by the Australian and South Australian Governments. Enquires should be addressed to: Goyder Institute for Water Research 209A Darling Building, North Terrace The University of Adelaide, Adelaide SA 5005 tel: (08) 8313 5020 e-mail: [email protected] Citation Prowse TAA (2020) Review of the ecology, status and modelling of waterbird populations of the Coorong South Lagoon. Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 20/12. © Crown in right of the State of South Australia, Department for Environment and Water, The University of Adelaide. Disclaimer This report has been prepared by The University of Adelaide (as the Goyder Institute for Water Research partner organisation) and contains independent scientific/technical advice to inform government decision- making. The independent findings and recommendations of this report are subject to separate and further consideration and decision-making processes and do not necessarily represent the views of the Australian Government or the South Australian Department for Environment and Water. -

Andaman and Nicobar Common Name Scientific Name

Andaman and Nicobar Common name Scientific name ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae Lesser Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna javanica Knob-billed Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea Cotton Pygmy-Goose Nettapus coromandelianus Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata Garganey Spatula querquedula Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Eurasian Wigeon Mareca penelope Indian Spot-billed Duck Anas poecilorhyncha Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Northern Pintail Anas acuta Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Andaman Teal Anas albogularis Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina Ferruginous Duck Aythya nyroca Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula GALLIFORMES: Megapodiidae Nicobar Scrubfowl Megapodius nicobariensis GALLIFORMES: Phasianidae Indian Peafowl Pavo cristatus Blue-breasted Quail Synoicus chinensis Common Quail Coturnix coturnix Jungle Bush-Quail Perdicula asiatica Painted Bush-Quail Perdicula erythrorhyncha Chinese Francolin Francolinus pintadeanus Gray Francolin Francolinus pondicerianus PODICIPEDIFORMES: Podicipedidae Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis Andaman and Nicobar COLUMBIFORMES: Columbidae Rock Pigeon Columba livia Andaman Wood-Pigeon Columba palumboides Eurasian Collared-Dove Streptopelia decaocto Red Collared-Dove Streptopelia tranquebarica Spotted Dove Streptopelia chinensis Laughing Dove Streptopelia senegalensis Andaman Cuckoo-Dove Macropygia rufipennis Asian Emerald Dove Chalcophaps indica Nicobar Pigeon Caloenas nicobarica Andaman Green-Pigeon Treron chloropterus Green Imperial-Pigeon Ducula aenea Nicobar Imperial-Pigeon Ducula nicobarica Pied Imperial-Pigeon -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

Predation of Flightless Pink-Footed Geese (Anser

RESEARCH NOTE Predation of flightless pink-footed geese (Anser brachyrhynchus) by Atlantic walruses (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) in southern Edgeøya, Svalbardpor_180 455..457 Anthony D. Fox,1 Gwen F. Fox,2 Arne Liaklev3 & Niklas Gerhardsson4 1 Department of Wildlife Ecology and Biodiversity, National Environmental Research Institute, Aarhus University, Kalø, Grenåvej 14, DK-8410 Rønde, Denmark 2 Ramtenvej 54, DK-8581 Nimtofte, Denmark 3 Rustefjelbma, NO-9845 Tana, Norway 4 Svalbard Huskies, PO Box 543, NO-9171 Longyearbyen, Svalbard, Norway Keywords Abstract Anserinae; mortality; moult migration. Observations of walrus (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) predation of flightless Correspondence pink-footed geese (Anser brachyrhynchus) at an important moult site in south- Anthony D. Fox, Department of Wildlife ern Edgeøya, Svalbard, constitute the first documented evidence of flightless Ecology and Biodiversity, National Anatidae being taken by this species. Environmental Research Institute, Aarhus University, Kalø, Grenåvej 14, DK-8410 Rønde, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] doi:10.1111/j.1751-8369.2010.00180.x A satellite telemetry study of Svalbard pink-footed geese was protected in 1952 (Norderhaug 1969; Lydersen et al. (Anser brachyrhynchus) showed that tagged non-breeding 2008). Since then, numbers have increased under protec- geese moved approximately 200 km east from potential tion, and some 79 haul-outs are known around the coasts breeding areas in western Spitsbergen, mostly to of Svalbard, amounting to an estimated total population Edgeøya, to undertake wing moult (Glahder et al. 2007). of 2629 (95% confidence interval [CI] 2318–2998) indi- Those authors contended that the non-breeding geese, viduals. One of the largest haul-outs is at Andreétangen freed from allegiance to brood-rearing areas, moved east (77°23′N, 22°37′E) in south-east Svalbard, where 125 to exploit the delayed thaw compared with central and were seen in August 2006 (Lydersen et al. -

The Role of Habitat Variability and Interactions Around Nesting Cavities in Shaping Urban Bird Communities

The role of habitat variability and interactions around nesting cavities in shaping urban bird communities Andrew Munro Rogers BSc, MSc Photo: A. Rogers A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 School of Biological Sciences Andrew Rogers PhD Thesis Thesis Abstract Inter-specific interactions around resources, such as nesting sites, are an important factor by which invasive species impact native communities. As resource availability varies across different environments, competition for resources and invasive species impacts around those resources change. In urban environments, changes in habitat structure and the addition of introduced species has led to significant changes in species composition and abundance, but the extent to which such changes have altered competition over resources is not well understood. Australia’s cities are relatively recent, many of them located in coastal and biodiversity-rich areas, where conservation efforts have the opportunity to benefit many species. Australia hosts a very large diversity of cavity-nesting species, across multiple families of birds and mammals. Of particular interest are cavity-breeding species that have been significantly impacted by the loss of available nesting resources in large, old, hollow- bearing trees. Cavity-breeding species have also been impacted by the addition of cavity- breeding invasive species, increasing the competition for the remaining nesting sites. The results of this additional competition have not been quantified in most cavity breeding communities in Australia. Our understanding of the importance of inter-specific interactions in shaping the outcomes of urbanization and invasion remains very limited across Australian communities. This has led to significant gaps in the understanding of the drivers of inter- specific interactions and how such interactions shape resource use in highly modified environments.