Nesting Biology. Social Patterns and Displays of the Mandarin Duck, a Ix Galericulata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

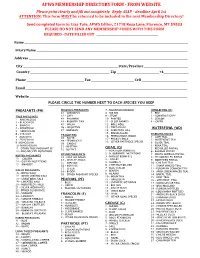

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - from WEBSITE Please Print Clearly and Fill out Completely

APWS MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - FROM WEBSITE Please print clearly and fill out completely. Reply ASAP – deadline April 1st ATTENTION: This form MUST be returned to be included in the next Membership Directory! Send completed form to: Lisa Tate, APWS Editor, 21718 Kesa Lane, Florence, MT 59833 PLEASE DO NOT SEND ANY MEMBERSHIP FUNDS WITH THIS FORM REQUIRED - DATE FILLED OUT ______________________________________________ Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Aviary Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City ________________________________________________________________________ State/Province _________________________________ Country ___________________________________________________________ Zip ________________________________+4___________________ Phone ___________________________________________ Fax ________________________________ Cell __________________________________ Email _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Website ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PLEASE CIRCLE THE NUMBER NEXT TO EACH SPECIES YOU KEEP PHEASANTS (PH) PEACOCK-PHEASANTS 7 - MOUNTAIN BAMBOO JUNGLEFOWL -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

DOE EA-2146 Final Environmental Assessment for the MARVEL

DOE/EA-2146 Final Environmental Assessment for the Microreactor Applications Research, Validation, and Evaluation (MARVEL) Project at Idaho National Laboratory June 2021 DOE/ID-2146 Final Environmental Assessment for the Microreactor Applications Research, Validation, and Evaluation (MARVEL) Project at Idaho National Laboratory June 2021 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy DOE Idaho Operations Office i i CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Purpose and Need ..................................................................................................................... 1 2. ALTERNATIVES .............................................................................................................................. 2 2.1 Proposed Action - Microreactor Applications Research, Validation and Evaluation (MARVEL) Project .................................................................................................................. 3 2.1.1 Reactor Structure System ............................................................................................ 5 2.1.2 Secondary Containment Structure .............................................................................. 5 2.1.3 Core System ............................................................................................................... -

Wood Duck (Aix Sponsa), EC 1606 (Oregon State University Extension

EC 1606 • April 2007 $1.00 Wood Duck Photo: Dave Menke, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Aix sponsa by Z. Turnbull and S. Sells he wood duck is so beautiful that its populations have increased, and today scientifi c name, Aix sponsa, means populations are at healthy levels. T “water bird in bridal dress.” Being Wood ducks are very popular for hunt- so beautiful (and tasty!), by the 1880s, ing. In fact, there are more wood ducks the once-abundant wood duck was disap- harvested each year in the United States pearing quickly due to hunting and habitat than any other game bird except mallards. loss. But not just hunters appreciate wood In the 1910s, wildlife managers acted ducks. Bird watchers and other people quickly to help save wood ducks. Laws who spend time outdoors love their were passed to protect migratory birds, beauty. hunting was controlled, and habitat was Common predators of wood ducks are protected. Wood duck nest boxes were raccoons, gray and red foxes, great horned created in the 1930s. Slowly, wood duck owls, some snakes, and minks. In a group of 10 newly hatched wood ducks, usu- ally only one or two survive past their fi rst 2 weeks. Predation is a main cause of such low survival rates. Dump nests occur when one or more females follow another to her nest and add their own eggs to the fi rst female’s eggs. When this occurs, there may be 50 or more eggs. They usually are abandoned, leading to a decline in successful hatch- ings in the area. -

Changes to Category C of the British List†

Ibis (2005), 147, 803–820 Blackwell Publishing, Ltd. Changes to Category C of the British List† STEVE P. DUDLEY* British Ornithologists’ Union, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK In its maintenance of the British List, the British Ornithologists’ Union Records Committee (BOURC) is responsible for assigning species to categories to indicate their status on the List. In 1995, the British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU) and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) held a conference on naturalized and introduced birds in Britain (Holmes & Simons 1996). This led to a review of the process of establishment of such species and the terms that best describe their status (Holmes & Stroud 1995) as well as a major review of the categorization of species on the British List (Holmes et al. 1998). The BOURC continues to review the occurrence and establishment of birds of captive origin in Britain. This paper sum- marizes the status of naturalized and introduced birds in Britain and announces changes to the categorization of many on the British List or its associated appendices (Categories D and E): Mute Swan Cygnus olor Categories AC change to AC2 Black Swan Cygnus atratus Category E* – no change Greylag Goose Anser anser Categories ACE* change to AC2C4E* Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Categories AE* change to AC2E* Greater Canada Goose Branta canadensis Categories ACE* change to C2E* Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis Categories AE* change to AC2E* Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiacus Categories CE* change -

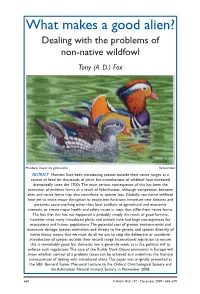

What Makes a Good Alien? Dealing with the Problems of Non-Native Wildfowl Tony (A

What makes a good alien? Dealing with the problems of non-native wildfowl Tony (A. D.) Fox Mandarin Ducks Aix galericulata Richard Allen ABSTRACT Humans have been introducing species outside their native ranges as a source of food for thousands of years, but introductions of wildfowl have increased dramatically since the 1700s.The most serious consequence of this has been the extinction of endemic forms as a result of hybridisation, although competition between alien and native forms may also contribute to species loss. Globally, non-native wildfowl have yet to cause major disruption to ecosystem functions; introduce new diseases and parasites; cause anything other than local conflicts to agricultural and economic interests; or create major health and safety issues in ways that differ from native forms. The fact that this has not happened is probably simply the result of good fortune, however, since many introduced plants and animals have had huge consequences for ecosystems and human populations.The potential cost of greater environmental and economic damage, species extinction, and threats to the genetic and species diversity of native faunas means that we must do all we can to stop the deliberate or accidental introduction of species outside their natural range. International legislation to ensure this is remarkably good, but domestic law is generally weak, as is the political will to enforce such regulations.The case of the Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis in Europe will show whether control of a problem taxon can be achieved and underlines the financial consequences of dealing with introduced aliens.This paper was originally presented as the 58th Bernard Tucker Memorial Lecture to the Oxford Ornithological Society and the Ashmolean Natural History Society, in November 2008. -

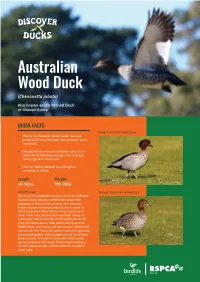

Australian Wood Duck (Chenonetta Jubata)

Australian Wood Duck (Chenonetta jubata) Also known as the ‘Maned Duck’ or ‘Maned Goose’ QUICK FACTS Male Australian Wood Duck • They are nicknamed ‘Maned Goose’ because people think they look more like miniature geese than ducks. • Wood Ducks love heavy rainfall because this is when the tastiest bugs emerge. They also love laying eggs after heavy rain. • They are better adapted to walking than swimming or diving. Length: Weight: 44–50cm 700–955g Identification: Female Australian Wood Duck The Australian Wood Ducks have earnt the nickname ‘Maned Goose’ because of their very goose-like appearance. The feathers around their neck and breast also give the impression of a lion’s mane. In flight, Australian Wood Ducks’ wings come out on show. Their wing tips are black and their wings are a pale grey with a white bar on the underside of the wing. Like many ducks, male and female Australian Wood Ducks vary in size and appearance. Males tend to have a darker head and smaller mane with speckled brown-grey bodies, a black undertail and black lower belly. Females have paler heads with white stripes above and below their eyes. Their breast and flanks are also speckled with a white undertail and white lower belly. BEHAVIOUR DISTRIBUTION & HABITAT Unlike most ducks, Australian Wood Ducks do not favour Australian Wood Ducks are found across most of Australia. swimming and will only enter open water if they’re Flocks of hundreds of birds can be found gathering disturbed. Instead, they prefer to waddle around and graze in southern areas of Australia in autumn and winter. -

Review of the Status of Introduced Non-Native Waterbird Species in the Area of the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement: 2007 Update

Secretariat provided by the Workshop 3 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Doc TC 8.25 21 February 2008 8th MEETING OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE 03 - 05 March 2008, Bonn, Germany ___________________________________________________________________________ Review of the Status of Introduced Non-Native Waterbird Species in the Area of the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement: 2007 Update Authors A.N. Banks, L.J. Wright, I.M.D. Maclean, C. Hann & M.M. Rehfisch February 2008 Report of work carried out by the British Trust for Ornithology under contract to AEWA Secretariat © British Trust for Ornithology British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU Registered Charity No. 216652 CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables...........................................................................................................................................5 List of Figures.........................................................................................................................................7 List of Appendices ..................................................................................................................................9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................11 RECOMMENDATIONS .....................................................................................................................13 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................15