The Date of Innocent I's Epistula 12 and the Second Exile of John

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

St. Augustine and the Doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ Stanislaus J

ST. AUGUSTINE AND THE DOCTRINE OF THE MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST STANISLAUS J. GRABOWSKI, S.T.D., S.T.M. Catholic University of America N THE present article a study will be made of Saint Augustine's doc I trine of the Mystical Body of Christ. This subject is, as it will be later pointed out, timely and fruitful. It is of unutterable importance for the proper and full conception of the Church. This study may be conveniently divided into four parts: (I) A fuller consideration of the doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, as it is found in the works of the great Bishop of Hippo; (II) a brief study of that same doctrine, as it is found in the sources which the Saint utilized; (III) a scrutiny of the place that this doctrine holds in the whole system of his religious thought and of some of its peculiarities; (IV) some consideration of the influence that Saint Augustine exercised on the development of this particular doctrine in theologians and doctrinal systems. THE DOCTRINE St. Augustine gives utterance in many passages, as the occasion de mands, to words, expressions, and sentences from which we are able to infer that the Church of his time was a Church of sacramental rites and a hierarchical order. Further, writing especially against Donatism, he is led Xo portray the Church concretely in its historical, geographical, visible form, characterized by manifest traits through which she may be recognized and discerned from false chuiches. The aspect, however, of the concept of the Church which he cherished most fondly and which he never seems tired of teaching, repeating, emphasizing, and expound ing to his listeners is the Church considered as the Body of Christ.1 1 On St. -

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period This volume is an investigation of how Augustine was received in the Carolingian period, and the elements of his thought which had an impact on Carolingian ideas of ‘state’, rulership and ethics. It focuses on Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims, authors and political advisers to Charlemagne and to Charles the Bald, respectively. It examines how they used Augustinian political thought and ethics, as manifested in the De civitate Dei, to give more weight to their advice. A comparative approach sheds light on the differences between Charlemagne’s reign and that of his grandson. It scrutinizes Alcuin’s and Hincmar’s discussions of empire, rulership and the moral conduct of political agents during which both drew on the De civitate Dei, although each came away with a different understanding. By means of a philological–historical approach, the book offers a deeper reading and treats the Latin texts as political discourses defined by content and language. Sophia Moesch is currently an SNSF-funded postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford, working on a project entitled ‘Developing Principles of Good Govern- ance: Latin and Greek Political Advice during the Carolingian and Macedonian Reforms’. She completed her PhD in History at King’s College London. Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period Political Discourse in Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims Sophia Moesch First published 2020 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Pelagius Britannicus

THE REAL 5TH-CENTURY PELAGIUS BRITANNICUS VS OUR ALLEGED 19TH-CENTURY “ULTIMATE PELAGIAN,” HENRICUS Bishop Augustine never met this monk and spiritual counselor Pelagius in person, even when he passed through Hippo in late 410. While in Rome, Pelagius had been the sponsor of a “moral rearmament” or “spiritual athleticism” movement. He seems to have been able to appeal particularly to affluent church ladies, whom he urged to set an example through works of virtue and ascetic living. The bishop saw the attitudes of Pelagius’s followers as dangerously similar to the error of Donatism, in that they fancied that they could by their own virtue set themselves apart from the common herd as ones upon whom God was particularly smiling. While Pelagius had gone off to the Holy Land and had there become an unwilling center of controversy as he visited sacred sites, others back in Africa were wading into this fracas with the hierarchical church authority Augustine. Whatever the merits of the case, of course the bishop’s side was going to prevail and the monk’s side was eventually going to be suppressed. How is this of relevance? Its relevance is due to the fact that, recently, in a book issued by the press of Thoreau’s alma mater Harvard University, Henry is being now characterized as the “ultimate Pelagian”! Go figure. “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Pelagianism HDT WHAT? INDEX PELAGIANISM PELAGIUS 355 CE Pelagius was born, presumably somewhere in the British Isles such as in Ireland (because of his name Brito or Britannicus — although the Pelagian Islands of Lampedusa, Linosa, and Lampione are in the Mediterranean between Tunisia and Malta). -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

Sunday, July 18 9 A.M. – Baptism Class – Pope John

ST. CASPAR CHURCH WAUSEON, OHIO July 18, 2021 Monday, July 19 Nothing scheduled Sunday, July 18 Tuesday, July 20 – St. Apollinaris, Bishop & Martyr 9 a.m. – Baptism Class – Pope John Room 8:30 a.m. for religious vocations 11:30 a.m. – New Parishioner Registration – NW Wednesday, July 21 – St. Lawrence of Brindisi, Priest & Doctor 5 p.m. – Spanish Rosary – South Wing of the Church 8:30 a.m. for all leaders Monday, July 19 Thursday, July 22 – St. Mary Magdalene 7 p.m. – Prayer Group – South Wing 8:30 a.m. for the homeless Friday, July 23 Friday, July 23 – St. Bridget, Religious 6:30 p.m. – Encuentro – North Wing 8:30 a.m. Adolfo Ferriera (1 year) Saturday, July 24 Saturday, July 24 5 p.m. for families 6 p.m. – Rosary – South Wing Chapel Sunday, July 25 – Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary Time 8 a.m. Lynn Keil Sunday, July 25 10:30 a.m. for St. Caspar parishioners 1 p.m. – Baptism – Church 1 p.m. for an end of abortion 5 p.m. – Spanish Rosary – South Wing Notre Dame Academy Seeks Host Families for Saturday, July 24– 5 p.m. International Students Arriving in August! Musicians: Proclaimer: Sally Kovar Do you want to learn more about another Servers: Ann Spieles & Brady Morr culture? Learn a new language, traditions, and food? Comm. Ministers: Roger & Cathy Drummer Then hosting an international student might be right Ushers: Team #1 (Jean LaFountain, Don Davis, Paul for you! Notre Dame Academy is seeking host Murphy) families for the 2021-22 school year. -

In This Week's Bulletin

CATHOLIC PARISH Diocese of Cleveland May 10, 2015 | Sixth Sunday of Easter IN THIS WEEK’S BULLETIN Parish Directory page 2 Women’s Guild Mother/Daughter Banquet Page 6 Loving God, Beyond We thank you for the love of the mothers you have given us, Driving with Dignity whose love is so precious that it can never be measured, Page 8 whose patience seems to have no end. May we see your loving hand behind them and guiding them. We pray for those mothers who fear they will run out of love or time or patience. We ask you to bless them with your own special love. We ask this in the name of Jesus, our brother. Amen. Saint Ambrose Catholic Parish | 929 Pearl Road, Brunswick, OH 44212 Phone | 330.460.7300 Fax |330.220.1748 Web | www.StAmbrose.us Sunday, May 10 | Mother’s Day THIS WEEK MARK YOUR CALENDARS 8:00 am-12:00 pm KofC Mother’s Day Breakfast (HH) 9:00-10:00 am Children’s Liturgy of the Word (CC) 10:30-11:30 am Children’s Liturgy of the Word (CC) 4:00-5:00 pm pm Cub Scouts (LCJN) Monday, May 11 May Crowning 9:00 am-5:00 pm Eucharistic Adoration (CC) Join Us! 6:00-8:00 pm Divorce Care for Kids (S) 6:00-8:00 pm Divorce Care (S) Tuesday | May 19, 2015 6:30-8:30 pm Scripture Study (LCMK) Time: 7:00pm 7:00-8:30 pm JH PSR Parent Meeting (LCJN) Procession to St. Ambrose Church 7:00-8:30 pm Youth & Young Adult Ministry (LCFM) Reception to follow in Hilkert Hall 7:00-9:00 pm Catholic Works of Mercy (LCMT) Tuesday, May 12 9:00-11:00 am Sarah’s Circle (LCMK) Saint Ambrose Directory 9:30 –11:30 am Ecumenical Women’s Breakfast (PCLMT) Here’s another 11:00 am-12:00 pm Music Ministry | New Life Choir (C) 6:00-8:00 pm CYO Volleyball (HHG) opportunity to have 7:00-8:00 pm Overeaters Anonymous (LCMT) your family picture 7:00-8:00 pm Worship Commission (HH) taken for our Parish 7:00-9:00 pm DBSA (LCJN) Directory! 7:00-9:00 pm Pastoral Council (PLCJP) 7:00-9:00 pm Knights of Columbus (LCFM) Photo Sessions will be held in the Lehner Center on: Wednesday, May 13 9:00-10:00 am Yoga (HH) Wednesday, May 13: 2-9pm 9:30-11:00 am Scripture Study (LCLK) Thursday, May 14: 2-9pm 1:00-2:00 pm Fr. -

The Development of Marian Doctrine As

INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON, OHIO in affiliation with the PONTIFICAL THEOLOGICAL FACULTY MARIANUM ROME, ITALY By: Elizabeth Marie Farley The Development of Marian Doctrine as Reflected in the Commentaries on the Wedding at Cana (John 2:1-5) by the Latin Fathers and Pastoral Theologians of the Church From the Fourth to the Seventeenth Century A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate in Sacred Theology with specialization in Marian Studies Director: Rev. Bertrand Buby, S.M. Marian Library/International Marian Research Institute University of Dayton 300 College Park Dayton, OH 45469-1390 2013 i Copyright © 2013 by Elizabeth M. Farley All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Nihil obstat: François Rossier, S.M., STD Vidimus et approbamus: Bertrand A. Buby S.M., STD – Director François Rossier, S.M., STD – Examinator Johann G. Roten S.M., PhD, STD – Examinator Thomas A. Thompson S.M., PhD – Examinator Elio M. Peretto, O.S.M. – Revisor Aristide M. Serra, O.S.M. – Revisor Daytonesis (USA), ex aedibus International Marian Research Institute, et Romae, ex aedibus Pontificiae Facultatis Theologicae Marianum, die 22 Augusti 2013. ii Dedication This Dissertation is Dedicated to: Father Bertrand Buby, S.M., The Faculty and Staff at The International Marian Research Institute, Father Jerome Young, O.S.B., Father Rory Pitstick, Joseph Sprug, Jerome Farley, my beloved husband, and All my family and friends iii Table of Contents Prėcis.................................................................................. xvii Guidelines........................................................................... xxiii Abbreviations...................................................................... xxv Chapter One: Purpose, Scope, Structure and Method 1.1 Introduction...................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose............................................................ -

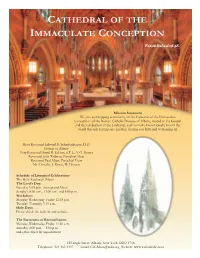

Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception

CATHEDRAL OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION Established 1848 Mission Statement We, the worshipping community of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany, rooted in the Gospel and the celebration of the Eucharist, seek to make known God’s love in the world through serving one another, sharing our faith and welcoming all. Most Reverend Edward B. Scharfenberger, D.D. Bishop of Albany Very Reverend David R. LeFort, S.T.L., V.G. Rector Reverend John Tallman, Parochial Vicar Reverend Paul Mijas, Parochial Vicar Mr. Timothy J. Kosto, II, Deacon Schedule of Liturgical Celebrations The Holy Eucharist (Mass) The Lord’s Day: Saturday 5:15 p.m. (anticipated Mass) Sunday’s 9:00 a.m., 11:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. Weekdays: Monday-Wednesday-Friday 12:15 p.m. Tuesday-Thursday 7:15 a.m. Holy Days: Please check the bulletin and website. The Sacrament of Reconciliation: Monday-Wednesday-Friday 11:30 a.m. Saturday 4:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. and other times by appointment 125 Eagle Street Albany, New York 12202-1718 Telephone: 518-463-4447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cathedralic.com CATHEDRAL OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION ALBANY Solemnity of the Epiphany of the Lord On the Sunday of the Epiphany of the Lord, we hear about gifts in the gospel reading. The image of gift is an appropriate one since to- day, on Epiphany Sunday, we acknowledge and celebrate the gift of God’s saving grace offered to everyone in the birth of his Son Je- sus. -

The Cambridge Companion to Age of Constantine.Pdf

The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine offers students a com- prehensive one-volume introduction to this pivotal emperor and his times. Richly illustrated and designed as a readable survey accessible to all audiences, it also achieves a level of scholarly sophistication and a freshness of interpretation that will be welcomed by the experts. The volume is divided into five sections that examine political history, reli- gion, social and economic history, art, and foreign relations during the reign of Constantine, a ruler who gains in importance because he steered the Roman Empire on a course parallel with his own personal develop- ment. Each chapter examines the intimate interplay between emperor and empire and between a powerful personality and his world. Collec- tively, the chapters show how both were mutually affected in ways that shaped the world of late antiquity and even affect our own world today. Noel Lenski is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. A specialist in the history of late antiquity, he is the author of numerous articles on military, political, cultural, and social history and the monograph Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century ad. Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S Edited by Noel Lenski University of Colorado Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo Cambridge University Press 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521818384 c Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

St. Bede & St. Cuthbert

THE PARISH OF St. Bede & St. Cuthbert Parish Priest: Canon Christopher Jackson 0191 388 2302 [email protected] Hospital Chaplain: Fr. Paul Tully 01388 818544 3rd January 2021 (2nd Sunday of Christmas) RIP Tom Walker May he rest in peace, and may his family be consoled by the faith in which he lived and died. COMING TO MASS? You must register if you want to attend Sunday mass either by email [email protected] or by phoning 07396643588; please give your name, phone number, postcode and house number; Registration for a Sunday begins on the previous Monday and ends at 3pm on the Friday. No need to register for weekdays. MASSES THIS WEEK Sunday 9.00 Linda Rowcroft St Bede’s 10.30 People of the Parish St Cuthbert’s Monday 10.00 Jim McGuire St Cuthbert’s Tuesday 11.30 Dr Anthony Hope St Cuthbert’s Wednesday 10.00 FEAST OF THE EPIPHANY St Cuthbert’s People of the Parish Thursday 10.00 Mary Bell St Bede’s Friday 10.00 Olga & Denny Corrigan St Bede’s Saturday 10.00 Deceased Crosby & Mc Loughlin families St Bede’s Sunday 9.00 People of the Parish St Bede’s 10.30 Mary Joseph Flaherty St Cuthbert’s ADORATION OF THE BLESSED SACRAMENT: Wednesday 9.30 St. Cuthbert’s Thursday 9.30 St. Bede’s CONFESSIONS: Wednesday 9.15am - 10 St Cuthbert’s Saturday 9.15am - 10 St Bede’s 0r by arrangement ROSARY: Saturday 9.40am St Bede’s FROM FR CHRIS VERY MANY THANKS for your good kind wishes, cards and gifts this Christmas; may the Christ Child bless you and your family.