The Earliest Western Evidence for Christmas and Epiphany Outside Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

St. Augustine and the Doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ Stanislaus J

ST. AUGUSTINE AND THE DOCTRINE OF THE MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST STANISLAUS J. GRABOWSKI, S.T.D., S.T.M. Catholic University of America N THE present article a study will be made of Saint Augustine's doc I trine of the Mystical Body of Christ. This subject is, as it will be later pointed out, timely and fruitful. It is of unutterable importance for the proper and full conception of the Church. This study may be conveniently divided into four parts: (I) A fuller consideration of the doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, as it is found in the works of the great Bishop of Hippo; (II) a brief study of that same doctrine, as it is found in the sources which the Saint utilized; (III) a scrutiny of the place that this doctrine holds in the whole system of his religious thought and of some of its peculiarities; (IV) some consideration of the influence that Saint Augustine exercised on the development of this particular doctrine in theologians and doctrinal systems. THE DOCTRINE St. Augustine gives utterance in many passages, as the occasion de mands, to words, expressions, and sentences from which we are able to infer that the Church of his time was a Church of sacramental rites and a hierarchical order. Further, writing especially against Donatism, he is led Xo portray the Church concretely in its historical, geographical, visible form, characterized by manifest traits through which she may be recognized and discerned from false chuiches. The aspect, however, of the concept of the Church which he cherished most fondly and which he never seems tired of teaching, repeating, emphasizing, and expound ing to his listeners is the Church considered as the Body of Christ.1 1 On St. -

The Fathers of the Church

THE FATHERS OF THE CHURCH A NEW TRANSLATION VOLUME 109 THE FATHERS OF THE CHURCH A NEW TRANSLATION EDITORIAL BOARD Thomas P. Halton 17ie Catholic University ofAmerica Editorial Director Elizabeth Clark Robert D. Sider Duhe University Dichinso n College Joseph T. Lienhard Michael Slusser Fordham University Duquesne University Frank A. C. Mantello Cynthia White 17ie Catholic University of America The University of Arizona Kathleen McVey Robin Darling Young Princeton 17ieological Seminary 17ie University of Notre Dame David]. McGonagle Director The Catholic University ofAmerica Press FORMER EDITORIAL DIRECTORS Ludwig Schopp, Roy J. Deferrari, Bernard M. Peebles, Hermigild Dressler, O.F.M. Joel Kalvesmaki Staff Editor ST.PETER CHRYSOLOGUS SELECTED SERMONS VOLUME 2 Translated by WILLIAM B. PALARDY St. John~, Seminary School of 17ieology Brighton, Massachusetts THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSI1Y OF AMERICA PRESS Washington, D.C. CONCORDIA THEOLOGIC/1L SEMINARY LIBRNiY FORT WAYNE, lf~DIM~P. 46825 In memory of my mother and father Copyright © 2004 THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSI1Y OF AMERICA PRESS All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standards for Information Science-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI z39.48 - 1984. LlnRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUilLICAT!ON DATA Peter, Cluysologus, Saint, Archbishop of Ravenna, ca. 400-450. [Sermons. English. Selections] St. Peter Cluysologus : selected sermons / translated by William B. l',1lanly. p. cm. - (The Fathers of the church, a new translation, v. 109) Vol. 1 published in 1953, by Fathers of the Church, New York, under title: Saint Peter Chrysologus : selected sermons; and Saint Valerian : homilies. -

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period This volume is an investigation of how Augustine was received in the Carolingian period, and the elements of his thought which had an impact on Carolingian ideas of ‘state’, rulership and ethics. It focuses on Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims, authors and political advisers to Charlemagne and to Charles the Bald, respectively. It examines how they used Augustinian political thought and ethics, as manifested in the De civitate Dei, to give more weight to their advice. A comparative approach sheds light on the differences between Charlemagne’s reign and that of his grandson. It scrutinizes Alcuin’s and Hincmar’s discussions of empire, rulership and the moral conduct of political agents during which both drew on the De civitate Dei, although each came away with a different understanding. By means of a philological–historical approach, the book offers a deeper reading and treats the Latin texts as political discourses defined by content and language. Sophia Moesch is currently an SNSF-funded postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford, working on a project entitled ‘Developing Principles of Good Govern- ance: Latin and Greek Political Advice during the Carolingian and Macedonian Reforms’. She completed her PhD in History at King’s College London. Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period Political Discourse in Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims Sophia Moesch First published 2020 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

July 25, 2021 the 17Th Sunday in Ordinary Time

Sunday, July 25, 2021 The 17th Sunday in Ordinary Time Diocese of Amarillo Most Rev. Patrick J. Zurek, Bishop Rev. Grant Spinhirne, Administrator St. Mary’s Holy Name of Jesus 22830 Pondaseta Road 317 W. Main P.O. Box 105 P.O. Box 128 Umbarger, TX 79091 Happy, TX 79042 (806) 499-3531 (806) 558-2871 WWW.STMARYSUMBARGER.COM Mass Schedule Umbarger Happy Mon, July 26 Sts. Joachim & Anne No Mass No Mass Tue, July 27 7 PM - Jim Grabber No Mass Wed, July 28 8 AM - Micky Porter No Mass Thu, July 29 St. Martha 8 AM - Knights of Columbus 7 PM - Fri, July 30 St. Peter Chrysologus 8 AM - Don & Amy Marshall No Mass Sat, July 31 St. Ignatius of Loyola No Mass 5:30 PM - Parish Family Sun, Aug 1 The 18th Sunday in 9:00 AM - Parish Family No Mass Ordinary Time Sunday, July 25, 2021 The 17th Sunday in Ordinary Time ST. MARY’S Divine Mercy Chaplet: 1st Sunday at 10:30 AM Tips on how to invite fallen-away Catholics back into Anointing of the Sick: By Request the Church th CYO 4 Sunday 6:00 pm. at the Hall By Philip Kosloski CCD: Sundays at 10:15-11:30 St. Ambrose suggests that gentleness and mercy are required Liturgy Sign-up Sheet: is located in the back of to welcome stray sheep back into the fold. the Church. Please sign up for Lector, Eucharistic Sometimes Catholics “fall away” from the Church for various Minister and Altar Servers! reasons, and many remain detached from the Church for the rest of their lives. -

Sunday, July 18 9 A.M. – Baptism Class – Pope John

ST. CASPAR CHURCH WAUSEON, OHIO July 18, 2021 Monday, July 19 Nothing scheduled Sunday, July 18 Tuesday, July 20 – St. Apollinaris, Bishop & Martyr 9 a.m. – Baptism Class – Pope John Room 8:30 a.m. for religious vocations 11:30 a.m. – New Parishioner Registration – NW Wednesday, July 21 – St. Lawrence of Brindisi, Priest & Doctor 5 p.m. – Spanish Rosary – South Wing of the Church 8:30 a.m. for all leaders Monday, July 19 Thursday, July 22 – St. Mary Magdalene 7 p.m. – Prayer Group – South Wing 8:30 a.m. for the homeless Friday, July 23 Friday, July 23 – St. Bridget, Religious 6:30 p.m. – Encuentro – North Wing 8:30 a.m. Adolfo Ferriera (1 year) Saturday, July 24 Saturday, July 24 5 p.m. for families 6 p.m. – Rosary – South Wing Chapel Sunday, July 25 – Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary Time 8 a.m. Lynn Keil Sunday, July 25 10:30 a.m. for St. Caspar parishioners 1 p.m. – Baptism – Church 1 p.m. for an end of abortion 5 p.m. – Spanish Rosary – South Wing Notre Dame Academy Seeks Host Families for Saturday, July 24– 5 p.m. International Students Arriving in August! Musicians: Proclaimer: Sally Kovar Do you want to learn more about another Servers: Ann Spieles & Brady Morr culture? Learn a new language, traditions, and food? Comm. Ministers: Roger & Cathy Drummer Then hosting an international student might be right Ushers: Team #1 (Jean LaFountain, Don Davis, Paul for you! Notre Dame Academy is seeking host Murphy) families for the 2021-22 school year. -

In This Week's Bulletin

CATHOLIC PARISH Diocese of Cleveland May 10, 2015 | Sixth Sunday of Easter IN THIS WEEK’S BULLETIN Parish Directory page 2 Women’s Guild Mother/Daughter Banquet Page 6 Loving God, Beyond We thank you for the love of the mothers you have given us, Driving with Dignity whose love is so precious that it can never be measured, Page 8 whose patience seems to have no end. May we see your loving hand behind them and guiding them. We pray for those mothers who fear they will run out of love or time or patience. We ask you to bless them with your own special love. We ask this in the name of Jesus, our brother. Amen. Saint Ambrose Catholic Parish | 929 Pearl Road, Brunswick, OH 44212 Phone | 330.460.7300 Fax |330.220.1748 Web | www.StAmbrose.us Sunday, May 10 | Mother’s Day THIS WEEK MARK YOUR CALENDARS 8:00 am-12:00 pm KofC Mother’s Day Breakfast (HH) 9:00-10:00 am Children’s Liturgy of the Word (CC) 10:30-11:30 am Children’s Liturgy of the Word (CC) 4:00-5:00 pm pm Cub Scouts (LCJN) Monday, May 11 May Crowning 9:00 am-5:00 pm Eucharistic Adoration (CC) Join Us! 6:00-8:00 pm Divorce Care for Kids (S) 6:00-8:00 pm Divorce Care (S) Tuesday | May 19, 2015 6:30-8:30 pm Scripture Study (LCMK) Time: 7:00pm 7:00-8:30 pm JH PSR Parent Meeting (LCJN) Procession to St. Ambrose Church 7:00-8:30 pm Youth & Young Adult Ministry (LCFM) Reception to follow in Hilkert Hall 7:00-9:00 pm Catholic Works of Mercy (LCMT) Tuesday, May 12 9:00-11:00 am Sarah’s Circle (LCMK) Saint Ambrose Directory 9:30 –11:30 am Ecumenical Women’s Breakfast (PCLMT) Here’s another 11:00 am-12:00 pm Music Ministry | New Life Choir (C) 6:00-8:00 pm CYO Volleyball (HHG) opportunity to have 7:00-8:00 pm Overeaters Anonymous (LCMT) your family picture 7:00-8:00 pm Worship Commission (HH) taken for our Parish 7:00-9:00 pm DBSA (LCJN) Directory! 7:00-9:00 pm Pastoral Council (PLCJP) 7:00-9:00 pm Knights of Columbus (LCFM) Photo Sessions will be held in the Lehner Center on: Wednesday, May 13 9:00-10:00 am Yoga (HH) Wednesday, May 13: 2-9pm 9:30-11:00 am Scripture Study (LCLK) Thursday, May 14: 2-9pm 1:00-2:00 pm Fr. -

Saints Peter and Paul Parish a Roman Catholic Faith Community

Saints Peter and Paul Parish A Roman Catholic Faith Community Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary Time July 24, 2016 You were buried with him in baptism, in which you were also raised with him through faith in the power of God, who raised him from the dead. — Colossians 2:12 Welcome To all who are tired and need rest; to all who mourn and need comfort; to all who are friendless and need friendship; to all who are discouraged and need hope; to all who are homeless and need sheltering love; and to all who sin and need a Savior; and to whomsoever will, the Parish of Saints Peter and Paul opens wide its doors in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ! Mission Statement As members of Saints Peter and Paul, we have as our mission the sharing of our faith and our talents. We proclaim the Word of God through compassion for our community and sharing of our treasures as Disciples of Christ. Office Mass Schedule 13 Hudson Road Monday – Communion Service – 7AM Plains, Pa 18705 Tuesday through Friday – 7AM (570)825-6663 Saturday 4PM (570)823-4556 fax Sunday 8AM & 11AM (570)656-2031 Fr. Jack www.sspeterandpaulplains.com Confessions Daily 6:30AM – 6:45AM Office Hours Saturday 3:00PM - 3:30PM Monday 10AM – 3PM And by appointment anytime Tuesday through Friday 8AM – 3PM Saturday by appointment Parish Center (570)822-8761 Working Together to Build the Kingdom of God M 7/25 7AM Communion Service T 7/26 7AM Barbara Olsakowski Daniel Pientka by Walter & Dorothy Lozinak W 7/27 7AM Guy DePasquale by Leo & Rose Pugh Our Lady of Lourdes Votive Candle Th 7/28 7AM Mike McGrady (A) by Sandy King Mary & Chester Baginski F 7/29 7AM Sophie Dreabit by Jim & Helen Zarichak S 7/30 4PM Patricia Bachman (A) by Sister & Family Our Holy Family Votive Candle S 7/31 8AM Robert Yakaski Irene Stanski by Irene Keil & Family 11AM Living and Deceased Parishioners July 17, 2016 Contribution $7,380 KEEP PRAYING Dues $3,079 St. -

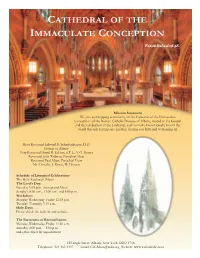

Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception

CATHEDRAL OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION Established 1848 Mission Statement We, the worshipping community of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany, rooted in the Gospel and the celebration of the Eucharist, seek to make known God’s love in the world through serving one another, sharing our faith and welcoming all. Most Reverend Edward B. Scharfenberger, D.D. Bishop of Albany Very Reverend David R. LeFort, S.T.L., V.G. Rector Reverend John Tallman, Parochial Vicar Reverend Paul Mijas, Parochial Vicar Mr. Timothy J. Kosto, II, Deacon Schedule of Liturgical Celebrations The Holy Eucharist (Mass) The Lord’s Day: Saturday 5:15 p.m. (anticipated Mass) Sunday’s 9:00 a.m., 11:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. Weekdays: Monday-Wednesday-Friday 12:15 p.m. Tuesday-Thursday 7:15 a.m. Holy Days: Please check the bulletin and website. The Sacrament of Reconciliation: Monday-Wednesday-Friday 11:30 a.m. Saturday 4:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. and other times by appointment 125 Eagle Street Albany, New York 12202-1718 Telephone: 518-463-4447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cathedralic.com CATHEDRAL OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION ALBANY Solemnity of the Epiphany of the Lord On the Sunday of the Epiphany of the Lord, we hear about gifts in the gospel reading. The image of gift is an appropriate one since to- day, on Epiphany Sunday, we acknowledge and celebrate the gift of God’s saving grace offered to everyone in the birth of his Son Je- sus. -

St. Bede & St. Cuthbert

THE PARISH OF St. Bede & St. Cuthbert Parish Priest: Canon Christopher Jackson 0191 388 2302 [email protected] Hospital Chaplain: Fr. Paul Tully 01388 818544 3rd January 2021 (2nd Sunday of Christmas) RIP Tom Walker May he rest in peace, and may his family be consoled by the faith in which he lived and died. COMING TO MASS? You must register if you want to attend Sunday mass either by email [email protected] or by phoning 07396643588; please give your name, phone number, postcode and house number; Registration for a Sunday begins on the previous Monday and ends at 3pm on the Friday. No need to register for weekdays. MASSES THIS WEEK Sunday 9.00 Linda Rowcroft St Bede’s 10.30 People of the Parish St Cuthbert’s Monday 10.00 Jim McGuire St Cuthbert’s Tuesday 11.30 Dr Anthony Hope St Cuthbert’s Wednesday 10.00 FEAST OF THE EPIPHANY St Cuthbert’s People of the Parish Thursday 10.00 Mary Bell St Bede’s Friday 10.00 Olga & Denny Corrigan St Bede’s Saturday 10.00 Deceased Crosby & Mc Loughlin families St Bede’s Sunday 9.00 People of the Parish St Bede’s 10.30 Mary Joseph Flaherty St Cuthbert’s ADORATION OF THE BLESSED SACRAMENT: Wednesday 9.30 St. Cuthbert’s Thursday 9.30 St. Bede’s CONFESSIONS: Wednesday 9.15am - 10 St Cuthbert’s Saturday 9.15am - 10 St Bede’s 0r by arrangement ROSARY: Saturday 9.40am St Bede’s FROM FR CHRIS VERY MANY THANKS for your good kind wishes, cards and gifts this Christmas; may the Christ Child bless you and your family. -

The Reformed Faith

THE REFORMED FAITH To describe the Reformed Faith in the limits of an article is no easy task. Any adequate account of it would require an expo- sition of the historical theological situation out of which it arose, and the theological views which it opposed. This in itself would be a task requiring too much space for an article in a theological Review. The mysticism which misunderstood the nature of revelation and minimised or destroyed the authority of the Word of God as the principium of theological knowledge ; the sacramentarianism and sacerdotalism of the Church of Rome, which denied the immediacy of the relation of the sinner to God in Salvation; the obscuration of the Augustinian conception of sovereign grace —all these theological movements would demand a somewhat lengthy consideration in order to reach an adequate understanding of the essential nature of the Reformed Faith. Obviously we must content ourselves with the mention of these theological errors which the Reformers opposed, and which met their most radical opposition in the Reformed Reformation. But if our task is not easy, it is, nevertheless timely and important. In this connection we would call attention to some trenchant words of Karl Barth1 in his Address, “ Reformed Doctrine, its Nature and Task.” He quotes from an account of the proceedings of a meeting of the eastern section of the Reformed World-Alliance held in Zurich in 1923. The words he quotes, he says, are from the pen of one of the leaders of that meeting. They are as follows : “ It could not escape an atten- tive observer, what a small role unfruitful theological discussions played in these days (i.e., of the meeting). -

St. Francis of Assisi Roman Catholic Church

ST. FRANCIS OF ASSISI ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH 136 Saxer Avenue, Springfield, Pa 19064 610-543-0848 (fax) 610-604-0283 www.sfaparish.org [email protected]. ST. FRANCIS OF ASSISI SCHOOL 610-543-0546 PASTOR WEEKEND ASSISTANT IN RESIDENCE IN RESIDENCE Rev. Matthew J. Tralies Rev. J. A. Grant Rev. Joseph J. Meehan Rev. Henry J. McKee Deacon W. Timothy Baxter Deacon James Kane STATEMENT OF ARCHBISHOP NELSON J. PÉREZ seventeenth Sunday in ordinary time REGARDING REINSTATING THE OBLIGATION TO ATTEND SUNDAY MASS “We have all felt the impact of COVID- 19 in as individuals and families. It has been a time of acute hardship and struggle, of separation and isolation. It has also had an impact on our lives of faith. Jesus Christ, our Lord and Savior, has been with us throughout this challenging period and is Sunday, July 25, 2021 most especially near to us when we encounter him in the Eucharist. The Eucharist offers us His healing and peace, His 7:30AM Deloris McFadden mercy and reconciliation. It is now time for everyone to return 9:30AM Josephine Strolle to the Eucharist with renewed faith and joy. 11:30AM Nigita Family As many aspects of life are now returning to normalcy, Monday, July 26, 2021 each Catholic Bishop in Pennsylvania will reinstate the obligation to attend Mass in person on Sundays and Holy 8:00AM The John Family Days beginning on Sunday, August 15, 2021, the Solemnity Tuesday, July 27, 2021 of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. 8:00AM Geraldine Curtin The Bishops previously jointly decided to dispense the faithful from this obligation in March of 2020 in order to Wednesday, July 28, 2021 provide for the common good given concerns over the 8:00AM Edward J.