The Reformed Faith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

St. Augustine and the Doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ Stanislaus J

ST. AUGUSTINE AND THE DOCTRINE OF THE MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST STANISLAUS J. GRABOWSKI, S.T.D., S.T.M. Catholic University of America N THE present article a study will be made of Saint Augustine's doc I trine of the Mystical Body of Christ. This subject is, as it will be later pointed out, timely and fruitful. It is of unutterable importance for the proper and full conception of the Church. This study may be conveniently divided into four parts: (I) A fuller consideration of the doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, as it is found in the works of the great Bishop of Hippo; (II) a brief study of that same doctrine, as it is found in the sources which the Saint utilized; (III) a scrutiny of the place that this doctrine holds in the whole system of his religious thought and of some of its peculiarities; (IV) some consideration of the influence that Saint Augustine exercised on the development of this particular doctrine in theologians and doctrinal systems. THE DOCTRINE St. Augustine gives utterance in many passages, as the occasion de mands, to words, expressions, and sentences from which we are able to infer that the Church of his time was a Church of sacramental rites and a hierarchical order. Further, writing especially against Donatism, he is led Xo portray the Church concretely in its historical, geographical, visible form, characterized by manifest traits through which she may be recognized and discerned from false chuiches. The aspect, however, of the concept of the Church which he cherished most fondly and which he never seems tired of teaching, repeating, emphasizing, and expound ing to his listeners is the Church considered as the Body of Christ.1 1 On St. -

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period This volume is an investigation of how Augustine was received in the Carolingian period, and the elements of his thought which had an impact on Carolingian ideas of ‘state’, rulership and ethics. It focuses on Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims, authors and political advisers to Charlemagne and to Charles the Bald, respectively. It examines how they used Augustinian political thought and ethics, as manifested in the De civitate Dei, to give more weight to their advice. A comparative approach sheds light on the differences between Charlemagne’s reign and that of his grandson. It scrutinizes Alcuin’s and Hincmar’s discussions of empire, rulership and the moral conduct of political agents during which both drew on the De civitate Dei, although each came away with a different understanding. By means of a philological–historical approach, the book offers a deeper reading and treats the Latin texts as political discourses defined by content and language. Sophia Moesch is currently an SNSF-funded postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford, working on a project entitled ‘Developing Principles of Good Govern- ance: Latin and Greek Political Advice during the Carolingian and Macedonian Reforms’. She completed her PhD in History at King’s College London. Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period Political Discourse in Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims Sophia Moesch First published 2020 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Faith and Life: Readings in Old Princeton Theology 05HT6160 RTS-Houston – Fall 2021 John R

Faith and Life: Readings in Old Princeton Theology 05HT6160 RTS-Houston – Fall 2021 John R. Muether ([email protected]) Meeting Dates October 1-2 (Friday and Saturday) December 3-4 (Friday and Saturday) Course Description A survey of the “majestic testimony” of Princeton Theological Seminary from its founding in 1812 to its reorganization in 1929, with readings from major figures including Archibald Alexander, Charles Hodge, Benjamin Warfield, and others. Emphasis will fall on its defense of the Reformed faith against the challenges of its time, its influence on the establishment of American Presbyterian identity, and its role in shaping contemporary American evangelicalism. Course Outline (Subject to Change) 1. Introduction: What was Old Princeton? 2. Archibald Alexander 3. Charles Hodge 4. A. A. Hodge 5. B. B. Warfield 6. Other Voices 7. J. G. Machen 8. Conclusion: The Legacy of Old Princeton Assignments 1. Completion of 1000 pages of reading. (10%) 2. Class presentation on a representative of Old Princeton theology (20%) 3. Research Paper (50%) 4. Class attendance and participation (20%) Readings Students will compile a reading list of primary and secondary sources in consultation with the instructor. It should include 1. Selections from Calhoun and/or Moorhead 2. Readings from at least four members of the Old Princeton faculty 3. At least two selections from both The Way of Life by Charles Hodge and Faith and Life by B. B. Warfield. 4. Resources for their class presentation and research paper. Research Paper The research paper is a 3000-4000 word paper which will explore in depth a particular figure in the story of Old Princeton. -

Sunday, July 18 9 A.M. – Baptism Class – Pope John

ST. CASPAR CHURCH WAUSEON, OHIO July 18, 2021 Monday, July 19 Nothing scheduled Sunday, July 18 Tuesday, July 20 – St. Apollinaris, Bishop & Martyr 9 a.m. – Baptism Class – Pope John Room 8:30 a.m. for religious vocations 11:30 a.m. – New Parishioner Registration – NW Wednesday, July 21 – St. Lawrence of Brindisi, Priest & Doctor 5 p.m. – Spanish Rosary – South Wing of the Church 8:30 a.m. for all leaders Monday, July 19 Thursday, July 22 – St. Mary Magdalene 7 p.m. – Prayer Group – South Wing 8:30 a.m. for the homeless Friday, July 23 Friday, July 23 – St. Bridget, Religious 6:30 p.m. – Encuentro – North Wing 8:30 a.m. Adolfo Ferriera (1 year) Saturday, July 24 Saturday, July 24 5 p.m. for families 6 p.m. – Rosary – South Wing Chapel Sunday, July 25 – Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary Time 8 a.m. Lynn Keil Sunday, July 25 10:30 a.m. for St. Caspar parishioners 1 p.m. – Baptism – Church 1 p.m. for an end of abortion 5 p.m. – Spanish Rosary – South Wing Notre Dame Academy Seeks Host Families for Saturday, July 24– 5 p.m. International Students Arriving in August! Musicians: Proclaimer: Sally Kovar Do you want to learn more about another Servers: Ann Spieles & Brady Morr culture? Learn a new language, traditions, and food? Comm. Ministers: Roger & Cathy Drummer Then hosting an international student might be right Ushers: Team #1 (Jean LaFountain, Don Davis, Paul for you! Notre Dame Academy is seeking host Murphy) families for the 2021-22 school year. -

POSTMODERN OR PROPOSITIONAL? Robert L

TMSJ 18/1 (Spring 2007) 3-21 THE NATURE OF TRUTH: POSTMODERN OR PROPOSITIONAL? Robert L. Thomas Professor of New Testament Ernest R. Sandeen laid a foundation for a contemporary concept of truth that was unique among evangelicals with a high view of Scripture. He proposed that the concept of inerrancy based on a literal method of interpretation was late in coming during the Christian era, having its beginning among the Princeton theologians of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He ruled out their doctrines related to inspiration because they were based on rational thinking which he taught was absent from earlier Christian thought. Subsequent evaluations of Sandeen’s work have disproved his assumption that those doctrines were absent from Christianity prior to the Princeton era. Yet well-known Christian writers have since built on Sandeen’s foundation that excludes rationality and precision from an interpretation of Scripture. The Sandeenists criticize the Princetonians for overreacting in their response to modernism, for their use of literal principles of interpretation, for defining propositional truth derived from the Bible, and for excluding the Holy Spirit’s help in interpretation. All such criticisms have proven to be without foundation. The Princetonians were not without fault, but their utilization of common sense in biblical interpretation was their strong virtue. Unfortunately, even the Journal of the inerrantist Evangelical Theological Society has promoted some of the same errors as Sandeen. The divine element in inspiration is a guarantee of the rationality and precision of Scripture, because God, the ultimate author of Scripture, is quite rational and precise, as proven by Scripture itself. -

In This Week's Bulletin

CATHOLIC PARISH Diocese of Cleveland May 10, 2015 | Sixth Sunday of Easter IN THIS WEEK’S BULLETIN Parish Directory page 2 Women’s Guild Mother/Daughter Banquet Page 6 Loving God, Beyond We thank you for the love of the mothers you have given us, Driving with Dignity whose love is so precious that it can never be measured, Page 8 whose patience seems to have no end. May we see your loving hand behind them and guiding them. We pray for those mothers who fear they will run out of love or time or patience. We ask you to bless them with your own special love. We ask this in the name of Jesus, our brother. Amen. Saint Ambrose Catholic Parish | 929 Pearl Road, Brunswick, OH 44212 Phone | 330.460.7300 Fax |330.220.1748 Web | www.StAmbrose.us Sunday, May 10 | Mother’s Day THIS WEEK MARK YOUR CALENDARS 8:00 am-12:00 pm KofC Mother’s Day Breakfast (HH) 9:00-10:00 am Children’s Liturgy of the Word (CC) 10:30-11:30 am Children’s Liturgy of the Word (CC) 4:00-5:00 pm pm Cub Scouts (LCJN) Monday, May 11 May Crowning 9:00 am-5:00 pm Eucharistic Adoration (CC) Join Us! 6:00-8:00 pm Divorce Care for Kids (S) 6:00-8:00 pm Divorce Care (S) Tuesday | May 19, 2015 6:30-8:30 pm Scripture Study (LCMK) Time: 7:00pm 7:00-8:30 pm JH PSR Parent Meeting (LCJN) Procession to St. Ambrose Church 7:00-8:30 pm Youth & Young Adult Ministry (LCFM) Reception to follow in Hilkert Hall 7:00-9:00 pm Catholic Works of Mercy (LCMT) Tuesday, May 12 9:00-11:00 am Sarah’s Circle (LCMK) Saint Ambrose Directory 9:30 –11:30 am Ecumenical Women’s Breakfast (PCLMT) Here’s another 11:00 am-12:00 pm Music Ministry | New Life Choir (C) 6:00-8:00 pm CYO Volleyball (HHG) opportunity to have 7:00-8:00 pm Overeaters Anonymous (LCMT) your family picture 7:00-8:00 pm Worship Commission (HH) taken for our Parish 7:00-9:00 pm DBSA (LCJN) Directory! 7:00-9:00 pm Pastoral Council (PLCJP) 7:00-9:00 pm Knights of Columbus (LCFM) Photo Sessions will be held in the Lehner Center on: Wednesday, May 13 9:00-10:00 am Yoga (HH) Wednesday, May 13: 2-9pm 9:30-11:00 am Scripture Study (LCLK) Thursday, May 14: 2-9pm 1:00-2:00 pm Fr. -

Adorable Trinity” Paul Kjoss Helseth

Charles Hodge on the Doctrine of the “Adorable Trinity” Paul Kjoss Helseth Paul Kjoss Helseth is Professor of Christian Thought at the University of Northwest- ern, St. Paul, Minnesota. He earned his PhD from Marquette University in Systematic Theology. Dr. Helseth is the author of“Right Reason” and the Princeton Mind: An Unorth- odox Proposal (P&R, 2010). He is also a contributor to Four Views on Divine Providence (Zondervan, 2011) and Reforming or Conforming?: Post-Conservative Evangelicals and the Emerging Church (Crossway, 2008). In addition, Dr. Helseth is co-editor of Reclaiming the Center: Confronting Evangelical Accommodation in Postmodern Times (Crossway, 2004) and Beyond the Bounds: Open Theism and the Undermining of Biblical Christianity (Crossway, 2003). Introduction Shortly after the untimely death of his brother’s son in December 1850, Charles Hodge wrote to his brother Hugh gently to remind him that the only way to cultivate the kind of sorrow that “is [in] every way healthful to the soul” is to mingle sorrow “with pious feeling, with resignation, confidence in God, [and] hope in his mercy and love.”1 “The great means of having our sorrow kept pure,” Hodge counseled, “is to keep near to God, to feel assured of his love, that he orders all things well, and will make even our afflictions work out for us a far more exceeding and an eternal weight of glory.”2 But precisely how did Hodge encourage his brother Hugh to “keep near to God,” and in so doing to cultivate the kind of sorrow that works life and not death, the kind of sorrow that is best described as “sorrow after a godly sort”?3 In short, Hodge encouraged his brother to cultivate godly and not “worldly”4 SBJT 21.2 (2017): 67-85 67 The Southern Baptist Journal of Theology 21.2 (2017) sorrow by remembering the doctrine of the Trinity. -

Faith and Learning the Heritage of J

REVIEW: Hoffecker’s Charles Hodge by Barry Waugh NewHorizons in the Orthodox Presbyterian Church OCT 2012 OCT Faith and LearninG The Heritage of J. Gresham Machen by Katherine VanDrunen ALSO: NEW BOOKS ON OLD PRINCETON by D. G. Hart and John R. Muether V o l u m e 3 3 , N u m b e r 9 NewHorizoNs iN tHe ortHodox PresbyteriaN CHurch Contents Editorial Board: The Committee on Christian Education’s Subcommittee on Serial Publications Editor: Danny E. Olinger FEATURES Managing Editor: James W. Scott Editorial Assistant: Patricia Clawson Cover Designer: Christopher Tobias 3 Faith and Learning: The Heritage of Proofreader: Sarah J. Pederson J. Gresham Machen © 2012 by The Committee on Christian Education of By Katherine VanDrunen The Orthodox Presbyterian Church. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are 6 The Personal Side of Charles Hodge from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a division of Good News Publish- By Alan D. Strange ers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Articles previously published may be slightly edited. The Legacy of Geerhardus Vos 8 New Horizons (ISSN: 0199-3518) is published monthly By Danny E. Olinger except for a combined issue, usually August-Septem- ber, by the Committee on Christian Education of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, 607 N. Easton Road, 19 Planning for a Minister’s Retirement Bldg. E, Willow Grove, PA 19090-2539; tel. 215/830- By Douglas L. Watson 0900; fax 215/830-0350. Letters to the editor are welcome. They should deal with an issue the magazine has recently addressed. -

Salvation in Christ.Qxp 4/29/2005 4:09 PM Page 299

Salvation in Christ.qxp 4/29/2005 4:09 PM Page 299 Those Who Have Never Heard: A Survey of the Major Positions John Sanders John Sanders is a professor of philosophy and religion at Huntington College, Huntington, Indiana. orphyry, a third-century philosopher and critic of Christianity, asked: “If Christ declares Himself to be the Way of salvation, the Grace and the Truth, and affirms that in Him alone, and Ponly to souls believing in Him, is the way of return to God, what has become of men who lived in the many centuries before Christ came? . What, then, has become of such an innumerable multitude of souls, who were in no wise blameworthy, seeing that He in whom alone saving faith can be exercised had not yet favoured men with His advent?”1 The force of his question was brought home to me personally when Lexi, our daughter whom we adopted from India as an older child, asked me whether her birth mother could be saved.2 The issue involves a large number of people since a huge part of the human race has died never hearing the good news of Jesus. It is estimated that in the year AD 100 there were 181 million people, 299 Salvation in Christ.qxp 4/29/2005 4:09 PM Page 300 Salvation in Christ of whom one million were Christians. It is also believed there were 60,000 unreached groups at that time. By AD 1000 there were 270 million people, 50 million of whom were Christians, with 50,000 un- reached groups. -

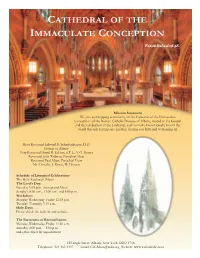

Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception

CATHEDRAL OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION Established 1848 Mission Statement We, the worshipping community of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany, rooted in the Gospel and the celebration of the Eucharist, seek to make known God’s love in the world through serving one another, sharing our faith and welcoming all. Most Reverend Edward B. Scharfenberger, D.D. Bishop of Albany Very Reverend David R. LeFort, S.T.L., V.G. Rector Reverend John Tallman, Parochial Vicar Reverend Paul Mijas, Parochial Vicar Mr. Timothy J. Kosto, II, Deacon Schedule of Liturgical Celebrations The Holy Eucharist (Mass) The Lord’s Day: Saturday 5:15 p.m. (anticipated Mass) Sunday’s 9:00 a.m., 11:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. Weekdays: Monday-Wednesday-Friday 12:15 p.m. Tuesday-Thursday 7:15 a.m. Holy Days: Please check the bulletin and website. The Sacrament of Reconciliation: Monday-Wednesday-Friday 11:30 a.m. Saturday 4:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. and other times by appointment 125 Eagle Street Albany, New York 12202-1718 Telephone: 518-463-4447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cathedralic.com CATHEDRAL OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION ALBANY Solemnity of the Epiphany of the Lord On the Sunday of the Epiphany of the Lord, we hear about gifts in the gospel reading. The image of gift is an appropriate one since to- day, on Epiphany Sunday, we acknowledge and celebrate the gift of God’s saving grace offered to everyone in the birth of his Son Je- sus. -

Does Classical Theism Deny God's Immanence?

Scholars Crossing LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations 2003 Does Classical Theism Deny God's Immanence? C. Fred Smith Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Smith, C. Fred, "Does Classical Theism Deny God's Immanence?" (2003). LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations. 147. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/147 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BiBLiOTHECA SACRA 160 (January-March 2003): 23-33 DOES CLASSICAL THEISM DENY GOD'S IMMANENCE? C. Fred Smith HE CONCEPT OF THE OPENNESS OF GOD has recently gained a foothold among some evangelical thinkers. Others who have T sought to refute this view have done so by emphasizing God's transcendent qualities. This article examines the criticism of clas sical theism by advocates of open theism and seeks to demonstrate that they portray classical theism inaccurately and that they have accepted a false understanding of God. OVERVIEW OF OPEN THEISM The movement's foundational text is The Openness of God, pub lished in 1994.l Most of what open theists have said since then amounts to a reiteration of arguments made in that book. Basic to open theism is the idea that God's being is analogous to that of humans, and so God experiences reality in ways similar to the ex periences of human beings. As evidence of this point Rice cites the fact that humankind is created in the image of God.2 In addition C.