Read Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Was There a Custom of Distributing the Booty in the Crusades of the Thirteenth Century?

Benjámin Borbás WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? MA Thesis in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies Central European University Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2019 WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, -

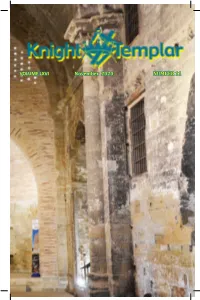

VOLUME LXVI November 2020 NUMBER 11

VOLUME LXVI November 2020 NUMBER 11 VOLUME LXVI NOVEMBER 2020 NUMBER 11 Published monthly as an official publication of the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar of the United States of America. Jeffrey N. Nelson Grand Master Jeffrey A. Bolstad Contents Grand Captain General and Publisher 325 Trestle Lane Grand Master’s Message Lewistown, MT 59457 Grand Master Jeffrey N. Nelson ..................... 4 Address changes or corrections La Forbie — The Beginning of the End and all membership activity for Frankish Outremer including deaths should be Sir Knight George L. Marshall, Jr., PGC ............. 7 reported to the recorder of the What’s the Point of a Sword? local Commandery. Please do Sir Knight John D. Barnes, PGC ...................... 12 not report them to the editor. Modern Day Chivalry Lawrence E. Tucker Sir Knight Thomas Hendrickson, PGM ........... 21 Grand Recorder Time To Move On Grand Encampment Office 5909 West Loop South, Suite 495 Reverend and Sir Knight J.B. Morris .............. 27 Bellaire, TX 77401-2402 Knights Templar Holy Land Pilgrimage Phone: (713) 349-8700 Fax: (713) 349-8710 for Sir Knights, their Ladies, and Friends ....... 30 E-mail: [email protected] Magazine materials and correspon- dence to the editor should be sent in elec- tronic form to the managing editor whose Features contact information is shown below. Materials and correspondence concern- Prelate’s Chapel ..................................................... 6 ing the Grand Commandery state supple- ments should be sent to the respective supplement editor. Focus on Chivalry .................................................. 14 John L. Palmer Leadership Notes - Delegating Effectively .............. 15 Managing Editor Post Office Box 566 The Knights Templar Eye Foundation ........5,16,17,20 Nolensville, TN 37135-0566 Phone: (615) 283-8477 Grand Commandery Supplement ......................... -

The Seventh Crusade ST

ST. MARY THE VIRGIN Sovereign Military Order of the Temple of Jerusalem The Seventh Crusade ST. MARY THE VIRGIN The Seventh Crusade First Edition 2021 Prepared by Dr. Chev. Peter L. Heineman, GOTJ, CMTJ 2020 Avenue B Council Bluffs, IA 51501 Phone 712.323.3531• www.plheineman.net Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Historical Context ....................................................................................... 2 The Campaign ........................................................................................... 3 Cyprus ............................................................................................. 4 Damietta .......................................................................................... 4 Cairo ............................................................................................... 5 Battle of Monsourah ........................................................................ 5 Battle of Fariskur ............................................................................. 6 Aftermath ................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION Seventh Crusade he Seventh Crusade (1248-1254) was led by the French king Louis IX (r. 1226-1270) who intended to conquer Egypt and take over Jerusalem; both then controlled by the Muslim Ayyubid Dynasty. Despite the initial success of capturing Damietta on the Nile, Louis' troops were defeated by the T -

Extracts from the Chronicles of Matthew Paris Relating to the Templars, Hospitallers and Teutonic Knights Translated from the Rolls Series Editions by Helen J

Cardiff University, School of History, Archaeology and Religion HS 1805 The Military Orders, 1100–1320; HST 908 The Military Orders Documents relating to the Military Orders Translated by Helen J. Nicholson. Original translations 1988–98; this edition 2013 Extracts from the chronicles of Matthew Paris relating to the Templars, Hospitallers and Teutonic Knights translated from the Rolls Series editions by Helen J. Nicholson Contents Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora [The Greater Chronicle] ...................................................................... 2 Vol. 3 .................................................................................................................................................... 2 About the Templars’ and Hospitallers’ pride and jealousy .............................................................. 2 The letter of Gerald, patriarch of Jerusalem ..................................................................................... 3 Thierry, the prior of the Hospital in England, is sent to help the Holy Land. ................................... 6 Vol. 4 .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Delightful events in the Holy Land about a peace treaty which had been made. But it had a very sad outcome. ..................................................................................................................................... 9 The Battle of La Forbie ................................................................................................................... -

History of the Crusades. Episode 100 Baibars. Wait, Did I Just Say Episode

History of the Crusades. Episode 100 Baibars. Wait, did I just say Episode 100? Woohoo! Wow, that seemed to go quickly. Even though there's clearly cause to celebrate, we have a lot to get through in this episode, so put the cork back in champagne bottles and we'd better press forward. So where am I? Here we go. Hello again. Last week we saw the Egyptian Mamluks defeat the Mongols in the Battle of Ain Jalut. Now it's hard to overstate the historical importance of this battle. The Egyptians were victorious, and their victory meant that the Mongol invasion was driven back, with its western borders now lying in Persia. Egypt then occupied all of Syria, and the Egyptian Mamluks went on to establish a power-base which would see them prevail as the dominant Muslim force in the Middle East until the rise of the Ottoman Empire in the 1400s. What would have happened if the Mongols won the Battle of Ain Jalut? Well, it's difficult to speculate, but Steven Runciman, in the third book of his trilogy on the Crusades, states that had the Mongols won the Battle of Ain Jalut, they no doubt would have pressed their advantage and gone on to conquer Egypt, meaning there would have been no great Muslim power remaining in the Middle East. The closest Muslim country would have been Morocco, far to the west in North Africa. Kitbuqa, the Mongol commander defeated at Ain Jalut, was a Nestorian Christian. Had he prevailed in battle, it's likely that the native Christians in the Middle East may have for the first time, risen to power under the Mongols. -

GURPS Crusades

CRUSADES TM Written by EUGENE MOYERS, with GRAEME DAVIS Edited by GRAEME DAVIS, ALAIN H. DAWSON, and JASON “PK” LEVINE Illustrated by PAUL DALY Cartography by ED BOURELLE An e23 Sourcebook for GURP S® STEVE JACKSON GAMES ® Stock #37-0608 Version 1.0 – November 2010 CONTENTS I NTRODUCTION . 3 THE FIFTH CRUSADE . 19 TEMPLATES . 31 Recommended Resources . 3 The Albigensian Crusade . 19 Suggested Equipment . 32 About the Author . 3 THE SIXTH CRUSADE . 20 Crusader Knight . 32 About GURPS . 3 THE SEVENTH CRUSADE . 20 Saracen Warrior . 33 The Shepherds’ Crusade . 21 Assassin . 33 HE ORLD OF 1. T W The Mongols . 21 A Wealth of Warriors . 34 THE RUSADES Religious Warrior . 34 C . 4 THE EIGHTH CRUSADE . 21 The Roman Empire . 4 THE NINTH CRUSADE . 22 5. BIOGRAPHIES . 35 THE FRANKS . 4 Other Crusades . 22 Richard I . 35 France . 4 Saladin . 36 England . 4 THE END COMES . 23 Reynald of Châtillon . 36 The Holy Roman Empire . 5 A T IMELINE OF THE CRUSADES . 23 Frederick II . 37 Spain . 5 Baldwin IV . 37 Italy . 5 Zengi . 38 The Norman Kingdoms . 5 Baibars . 38 The Latin Kingdoms . 5 This age is like Other Biographies . 38 The Military Orders . 5 no other . THE GREEKS . 7 6. CAMPAIGNS . 39 THE MUSLIMS . 7 – St. Bernard CAMPAIGN STYLES . 39 Shiites and Sunnis . 7 of Clervaux Realistic Campaigns . 39 The Assassins . 8 Action-Adventure The Turks . 8 Campaigns . 39 The Saracens . 9 Cinematic Campaigns . 39 Egypt . 9 3. LIFE DURING CAMPAIGN SETTINGS . 40 The Barbary Corsairs . 9 Fantasy Campaigns . 40 THE CRUSADES . 24 The Gnostic Gospels . 40 HE ISTORY OF 2. -

Diplomacy, Society, and War in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, C.1240-1291

The Frankish Nobility and The Fall of Acre: Diplomacy, Society, and War in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, c.1240-1291 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Jesse W. Izzo IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Michael Lower October 2016 © Jesse W. Izzo, May 2016 i Acknowledgements It is a welcome task indeed to thank some of the many individuals and institutions that have helped me bring this project to fruition. I have enjoyed a good deal of financial support from various institutions without which this project would not have been possible. I extend my heartfelt thanks to the UMN Graduate School and College of Liberal Arts; to the History Department; to the Centers for Medieval Studies and Early Modern History at Minnesota; to the U.S. Department of Education for providing me with a Foreign Language and Area Studies award to study Arabic; and to the U.S.-Israel Education Foundation and Fulbright program, for making possible nine months of research in Jerusalem I cannot name all the marvelous educators I had in secondary school, so O.J. Burns and Ian Campbell of Greens Farms Academy in Westport, CT, two of the very best there have ever been, will need to stand for everyone. Again, I had too many wonderful professors as an undergraduate to thank them all by name, but I do wish to single out Paul Freedman of Yale University for advising my senior essay. My M.Phil. supervisor, Jonathan Riley-Smith, emeritus of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, helped set me on my way in researching the Crusades and the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, as he has done for so many students before me. -

Ayyubids, Mamluks, and the Latin East in the Thirteenth Century*

R. STEPHEN HUMPHREYS UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA Ayyubids, Mamluks, and the Latin East in the Thirteenth Century* There was, once upon a time, a widely accepted myth that the Muslim rulers and peoples of southwest Asia were from the outset bitterly opposed to the presence among them of the Crusaders (variously portrayed as infidels or proto-imperialists), and that they struggled unceasingly if ineffectually to expel them. But that myth has long since been discarded among serious scholars. A series of essays in the mid-1950s by Claude Cahen and Sir Hamilton Gibb demonstrated that we can only perceive a consistent policy and ideology of opposition to the Crusades with the rise to power of Nu≠r al-D|n (r. 1146-1174), and then in a more heightened manner under Saladin (r. 1169-1193). A more precise definition of this process, covering the whole two centuries of Crusader rule in Syria-Palestine, was developed for the first time in the splendid monograph of Emmanuel Sivan, L'Islam et la Croisade. Sivan almost certainly understated the sanctity of Jerusalem in Islamic consciousness in the pre-Crusade era, and he may not have done justice to the military efforts of the later Fatimids and the Saljuq amirs of Syria, both of whom had to contend with a very unfamiliar threat from a position of grave weakness. But on balance his account remains the best introduction to the subject of the "Counter-Crusade." 1 In spite of Sivan's important contribution, however, the nature of the relations between the Muslim rulers of Syria and Egypt and the Crusader states after the death of Saladin (1193) has remained something of a puzzle. -

History of the Crusades. Episode 90 Disaster Strikes. Hello Again

History of the Crusades. Episode 90 Disaster Strikes. Hello again. Last week, following the Barons’ Crusade, we saw the territory of the Kingdom of Acre expand to levels not seen since the Battle of Hattin. The expansion of territory on paper, however, masked internal disunity within the Crusader states, as the military Orders clashed with each other, and the factions of local noblemen fought for supremacy. Across the Muslim world too, things were in a state of flux, as various Muslim leaders jostled for position following the death of al-Kamil. Panning out even further, the wider region of Asia was experiencing instability as the invading Mongol armies pushed out of the steppe region, conquering territory and displacing local people. One of the many people displaced by the all-conquering Mongols were the Khwarezmians. A Muslim Turkish people, the Khwarezmians had originally themselves displaced the Seljuk Turks, and had settled on land extending from India to Iraq. Fleeing before the Mongol invasion, the Khwarezmians found themselves being pushed westwards towards the Holy Land. Surviving for the moment as mercenaries, but hoping to conquer enough territory to establish a new homeland, the Khwarezmians were approached by al-Kamil’s eldest son, al-Salih Ayyub, who wished to secure their services. In exchange for money and land, al-Salih engaged the Khwarezmians to attack Syria, hoping to use them to crush the ambitions of both his uncle Ismail of Damascus and his cousin al-Nasir of Kerak. In June 1244, an army of over 10,000 Khwarezmian horsemen galloped westwards into the territory controlled by Ismail of Damascus, killing indiscriminately, burning villages, looting, and pillaging. -

Crusader Art in the Holy Land, from the Third Crusade to the Fall of Acre, 1187 -- 1291

Crusader Art in the Holy Land, from the Third Crusade to the Fall of Acre, 1187 -- 1291 General Subject Index Note: A manuscript index arranged by repository name is to be found at the end of the printed work Abbasid caliphate, 366 Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 7 Acre aerial photo, fig. 61 architectural studies of, 523 artistic production at, lxv, lxvii, 303–4 (See also Acre, manuscripts; Acre, scriptorium) baillage of, 160–61 banners of, 38, 569n141 Baybars’s attack on, 262, 264, 266, 267 Béguines in, 275 Benedictines in, 400 Burchard of Mount Sion on, 388, 399, 400 Carmelites in, 400 cemeteries of, 247, 274, 356, 564n168 Christian schools of, 400 churches of, 38, 60, 61, 182, 183–84, 274–75, 388, 604n377, 605n403, 622n395 Gothic, 8, 279–80 Templar, 183 Cistercians in, 400 coinage of, 48, 205, 258, 316, 505, 514, 677n152, figs 12-16, fig. 36–38, fig. 111–12, fig. 163, plate 7 coin hoard, 505, 677n152 commerce of, 60, 61, 62, 397, 398, 632n660, 652n283 commune end of, 169 formation of, 158, 227 impact on artistic activity, 174, 227 John of Ibelin’s mayorality of, 161 2 confraternities of, 61, 633n685 convents of, 183, 362 Crusader reconquest of, 30, 48, 53, 60, 515 cultural life of, 274, 400 destruction of art at, 38, 469, 569n144 distance from Safed, 621n336 Dominicans in, 183, 296, 630n591, 653n314 in earthquake of 1202, 125, 184 Eastern Christians of, 183, 398, 574n46 Arabs, 627n501 economy of, 394, 397 effect of mercantile conflict on, 255 emergency coinage of, 145 excavation of, 15, 183, 227, 275, 280, 359, 404, 504, 605n378, 670n635, 674n91 fall of (1291), 183, 274, 340, 403, 482–91, 525 aftermath, 506–7 captives from, 489–90 clergy after, 491, 511 Crusader art following, 507–10, 525 Crusaders following, 507 defenders in, 485–86 Henry II in, 486 Hospitallers in, 485, 486, 487 Jacques de Vitry on, 480 mourning for, 489 in pilgrims’ accounts, 488–91 public opinion on, 507 razing of, 489 siege, 484–89 spolia from, 489, 491, 673n70 St. -

Coins of the CRUSADERS

Coins of the CRUSADERS The Crusades were a series of military conflicts of a religious character waged by much of Christian Europe against external and internal threats. Crusades were fought against Muslims, pagan Slavs, Russian and Greek Orthodox Christians, Mongols, Cathars, Hussites, and political enemies of the popes.[1] Crusaders took vows and were granted an indulgence for past sins. The Crusades originally had the goal of recapturing Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Muslim rule and were original- ly launched in response to a call from the Eastern Orthodox Byzantine Empire for help against the expansion of the Muslim Seljuk Turks into Anatolia. The term is also used to describe contemporaneous and subsequent campaigns conducted through to the 16th century in territories outside the Levant usually against pagans, heretics, and peoples under the ban of excommunication for a mixture of religious, economic, and political reasons. Rivalries among both Christian and Muslim powers led also to alliances between religious factions against their opponents, such as the Christian alliance with the Sultanate of Rum during the Fifth Crusade. The Crusades had far-reaching political, economic, and social impacts, some of which have lasted into contemporary times. Because of internal conflicts among Christian kingdoms and political powers, some of the crusade expeditions were diverted from their original aim, such as the Fourth Crusade, which resulted in the sack of Christian Constantinople and the partition of the Byzantine Empire between Venice and the Crusaders. The Sixth Crusade was the first crusade to set sail without the official blessing of the Pope, establishing the precedent that rulers other than the Pope could initiate a crusade. -

The Knights Templar

Sovereign Order of the Elder Brethren Rose Cross Founded in 1317 by Pope John XXII of Avignon (France) The Knights Templar Brief History of the Crusades and Knights Templar by Philippe L. De Coster, B.Th.,D.D. Grand Master General of O.S.F.A.R.C © April 2013 – Philippe L. De Coster, Ghent, Belgium (Non-Commercial) Sovereign Order of the Elder Brethren Rose Cross Founded in 1317 by Pope John XXII of Avignon (France) The Knight Templars Brief History of the Crusades and Knight Templars by Philippe L. De Coster, B.Th.,D.D. Grand Master General of O.S.F.A.R.C “Journey Through the Mysterious Labyrinth of the Knights Templar” © April 2013 – Philippe L. De Coster, Ghent, Belgium (Non-Commercial) 2 The Knights Templar Brief History of the Crusades Sometime between 1110 and 1120, in the aftermath of the First Crusade, a small group of knights vowed to devote their lives to the protection of pilgrims in the Holy Land. They were called the 'Order of the Poor Knights of Christ.' The King of Jerusalem, Baldwin II, granted them the use of a captured mosque built on Temple Mount in Jerusalem, the site of the ancient Temple of Solomon. From this they became known as the Knights Templar. Under the patronage of St. Bernard of Clairvaux the Order received papal sanction and legitimacy. The Knights Templar were granted permission by the pope to wear a distinctive white robe with a red cross. Within a hundred years the Order owned land all over Europe and had amassed considerable wealth.