Was There a Custom of Distributing the Booty in the Crusades of the Thirteenth Century?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Throughout Anglo-Saxon and Norman Times, Many People – Not Just Rich Kings and Bishops

THE CRUSADES: A FIGHT IN THE NAME OF GOD. Timeline: The First Crusade, 1095-1101; The Second Crusade, 1145-47; The Third Crusade, 1188-92; The Fourth Crusade, 1204; The Fifth Crusade, 1217; The Sixth Crusade, 1228-29, 1239; The Seventh Crusade, 1249-52; The Eighth Crusade, 1270. Throughout Anglo-Saxon and Norman times, many people – not just rich kings and bishops - went to the Holy Land on a Pilgrimage, despite the long and dangerous journey – which often took seven or eight years! When the Turks conquered the Middle East this was seen as a major threat to Christians. [a] Motives for the Crusades. 1095, Pope Urban II. An accursed race has violently invaded the lands of the Christians. They have destroyed the churches of God or taken them for their own religion. Jerusalem is now held captive by the enemies of Christ, subject to those who do not know God – the worship of the heathen….. He who makes this holy pilgrimage shall wear the sign of the cross of the Lord on his forehead or on his breast….. If you are killed your sins will be pardoned….let those who have been fighting against their own brothers now fight lawfully against the barbarians…. A French crusader writes to his wife, 1098. My dear wife, I now have twice as much silver, gold and other riches as I had when I set off on this crusade…….. A French crusader writes to his wife, 1190. Alas, my darling! It breaks my heart to leave you, but I must go to the Holy land. -

THE CRUSADES Toward the End of the 11Th Century

THE MIDDLE AGES: THE CRUSADES Toward the end of the 11th century (1000’s A.D), the Catholic Church began to authorize military expeditions, or Crusades, to expel Muslim “infidels” from the Holy Land!!! Crusaders, who wore red crosses on their coats to advertise their status, believed that their service would guarantee the remission of their sins and ensure that they could spend all eternity in Heaven. (They also received more worldly rewards, such as papal protection of their property and forgiveness of some kinds of loan payments.) ‘Papal’ = Relating to The Catholic Pope (Catholic Pope Pictured Left <<<) The Crusades began in 1095, when Pope Urban summoned a Christian army to fight its way to Jerusalem, and continued on and off until the end of the 15th century (1400’s A.D). No one “won” the Crusades; in fact, many thousands of people from both sides lost their lives. They did make ordinary Catholics across Christendom feel like they had a common purpose, and they inspired waves of religious enthusiasm among people who might otherwise have felt alienated from the official Church. They also exposed Crusaders to Islamic literature, science and technology–exposure that would have a lasting effect on European intellectual life. GET THE INFIDELS (Non-Muslims)!!!! >>>> <<<“GET THE MUSLIMS!!!!” Muslims From The Middle East VS, European Christians WHAT WERE THE CRUSADES? By the end of the 11th century, Western Europe had emerged as a significant power in its own right, though it still lagged behind other Mediterranean civilizations, such as that of the Byzantine Empire (formerly the eastern half of the Roman Empire) and the Islamic Empire of the Middle East and North Africa. -

Geoffrey of Dutton, the Fifth Crusade, and the Holy Cross of Norton

A Transformed Life? Geoffrey of Dutton, the Fifth Crusade, and the Holy Cross of Norton. Despite the volume of scholarship dedicated to crusade motivation, comparative little has been said on how the crusades affected the lives of individuals, and how this played out once the returned home. Taking as a case study a Cheshire landholder, Geoffrey of Dutton, this article looks at the reasons for his crusade participation and his actions once he returned to Cheshire, arguing that he was changed by his experiences to the extent that he was concerned with remembering and conveying his own status as a returned pilgrim. It also looks at the impact of a relic of the True Cross he brought back and gave to the Augustinian priory of Norton. Keywords: crusade; relic; Norton Priory; burial; seal An extensive body of scholarship has considered what motivated people to go on crusade in the middle ages (piety, obligation and service, family connections and ties of lordship, punishment and escape), as well as what impact that had across Europe in terms of recruitment, funding and organisation. Far less has been said about the more personal impact of crusading for individuals who took part. This is largely due to the nature of the sources from which, according to Housley, ‘not much can be inferred…about the response of the majority of crusaders to what they’d gone through in the East.’1 With the exception of accounts of the post-crusading careers of the most important individuals, notably Louis IX of France, very little was written about how crusaders responded to taking part in an overseas campaign which mixed the height of spiritual endeavour with extreme violence. -

A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2014 A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E. Tobias Osterhaug Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Osterhaug, Tobias, "A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E." (2014). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 25. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/25 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Tobias Osterhaug History 499/Honors 402 A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E. Introduction: The first Crusade, a massive and unprecedented undertaking in the western world, differed from the majority of subsequent crusades into the Holy Land in an important way: it contained no royalty and was undertaken with very little direct support from the ruling families of Western Europe. This aspect of the crusade led to the development of sophisticated hierarchies and vassalages among the knights who led the crusade. These relationships culminated in the formation of the Crusader States, Latin outposts in the Levant surrounded by Muslim states, and populated primarily by non-Catholic or non-Christian peoples. Despite the difficulties engendered by this situation, the Crusader States managed to maintain control over the Holy Land for much of the twelfth century, and, to a lesser degree, for several decades after the Fall of Jerusalem in 1187 to Saladin. -

Louis Ix, King of France

pg 1/3 King Louis IX of France Born: 25 Apr 1215 Poissy, FRA Married: Margarite de Provence Died: 25 Aug 1270 FRA Parents: King Louis VIII & Blanche de Castile Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 to his death. He was also Count of Artois (as Louis II) from 1226 to 1237. Born at Poissy, near Paris, he was a member of the House of Capet and the son of King Louis VIII and Blanche of Castile. He is the only canonised king of France and consequently there are many places named after him, most notably St. Louis, Missouri in the United States. He established the Parlement of Paris. Early life Louis was born in 1214 at Poissy, near Paris, the son of King Louis VIII and Blanche of Castile. A member of the House of Capet, Louis was twelve years old when his father died on November 8, 1226. He was crowned king the same year in the cathedral at Reims. Because of Louis's youth, his mother ruled France as regent during his minority. His younger brother Charles I of Sicily (1227–85) was created count of Anjou, thus founding the second Angevin dynasty. The horrific fate of that dynasty in Sicily as a result of the Sicilian Vespers evidently did not tarnish Louis's credentials for sainthood. No date is given for the beginning of Louis's personal rule. His contemporaries viewed his reign as co-rule between the king and his mother, though historians generally view the year 1234 as the year in which Louis began ruling personally, with his mother assuming a more advisory role. -

The Idea of Medieval Heresy in Early Modern France

The Idea of Medieval Heresy in Early Modern France Bethany Hume PhD University of York History September 2019 2 Abstract This thesis responds to the historiographical focus on the trope of the Albigensians and Waldensians within sixteenth-century confessional polemic. It supports a shift away from the consideration of medieval heresy in early modern historical writing merely as literary topoi of the French Wars of Religion. Instead, it argues for a more detailed examination of the medieval heretical and inquisitorial sources used within seventeenth-century French intellectual culture and religious polemic. It does this by examining the context of the Doat Commission (1663-1670), which transcribed a collection of inquisition registers from Languedoc, 1235-44. Jean de Doat (c.1600-1683), President of the Chambre des Comptes of the parlement of Pau from 1646, was charged by royal commission to the south of France to copy documents of interest to the Crown. This thesis aims to explore the Doat Commission within the wider context of ideas on medieval heresy in seventeenth-century France. The periodization “medieval” is extremely broad and incorporates many forms of heresy throughout Europe. As such, the scope of this thesis surveys how thirteenth-century heretics, namely the Albigensians and Waldensians, were portrayed in historical narrative in the 1600s. The field of study that this thesis hopes to contribute to includes the growth of historical interest in medieval heresy and its repression, and the search for original sources by seventeenth-century savants. By exploring the ideas of medieval heresy espoused by different intellectual networks it becomes clear that early modern European thought on medieval heresy informed antiquarianism, historical writing, and ideas of justice and persecution, as well as shaping confessional identity. -

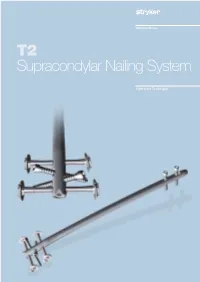

T2 Supracondylar Nailing System

T2 Supracondylar Nailing System Operative Technique Supracondylar Nailing System Contributing Surgeons Prof. Dr. med. Volker Bühren Chief of Surgical Services Medical Director of Murnau Trauma Center Murnau Germany Dean C. Maar, M.D. Methodist Hospital − Indianapolis Indianapolis Indiana USA James Maxey, M.D. Clinical Assistant Professor University of Illinois College of Medicine Peoria, IL USA This publication sets forth detailed recommended procedures for using Stryker Osteosynthesis devices and instruments. It offers guidance that you should heed, but, as with any such technical guide, each surgeon must consider the particular needs of each patient and make appropriate adjustments when and as required. A workshop training is required prior to first surgery. All non-sterile devices must be cleaned and sterilized before use. Follow the instructions provided in our reprocessing guide (L24002000). Multi-component instruments must be disassembled for cleaning. Please refer to the corresponding assembly/ disassembly instructions. See package insert (L22000007) for a complete list of potential adverse effects, contraindications, warnings and precautions. The surgeon must discuss all relevant risks, including the finite lifetime of the device, with the patient, when necessary. Warning: All bone screws referenced in this document here are not approved for screw attachment or fixation to the posterior elements (pedicles) of the cervical, thoracic or lumbar spine. 2 Contents Page 1. Introduction 4 Implant Features 4 Technical Details 5 Instrument -

Download Date 04/10/2021 06:40:30

Mamluk cavalry practices: Evolution and influence Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nettles, Isolde Betty Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 06:40:30 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289748 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this roproduction is dependent upon the quaiity of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that tfie author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal secttons with small overlaps. Photograpiis included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrattons appearing in this copy for an additk)nal charge. -

Sir Walter Scott's Templar Construct

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. SIR WALTER SCOTT’S TEMPLAR CONSTRUCT – A STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY INFLUENCES ON HISTORICAL PERCEPTIONS. A THESIS PRESENTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY AT MASSEY UNIVERSITY, EXTRAMURAL, NEW ZEALAND. JANE HELEN WOODGER 2017 1 ABSTRACT Sir Walter Scott was a writer of historical fiction, but how accurate are his portrayals? The novels Ivanhoe and Talisman both feature Templars as the antagonists. Scott’s works display he had a fundamental knowledge of the Order and their fall. However, the novels are fiction, and the accuracy of some of the author’s depictions are questionable. As a result, the novels are more representative of events and thinking of the early nineteenth century than any other period. The main theme in both novels is the importance of unity and illustrating the destructive nature of any division. The protagonists unify under the banner of King Richard and the Templars pursue a course of independence. Scott’s works also helped to formulate notions of Scottish identity, Freemasonry (and their alleged forbearers the Templars) and Victorian behaviours. However, Scott’s image is only one of a long history of Templars featuring in literature over the centuries. Like Scott, the previous renditions of the Templars are more illustrations of the contemporary than historical accounts. One matter for unease in the early 1800s was religion and Catholic Emancipation. -

VOLUME LXVI November 2020 NUMBER 11

VOLUME LXVI November 2020 NUMBER 11 VOLUME LXVI NOVEMBER 2020 NUMBER 11 Published monthly as an official publication of the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar of the United States of America. Jeffrey N. Nelson Grand Master Jeffrey A. Bolstad Contents Grand Captain General and Publisher 325 Trestle Lane Grand Master’s Message Lewistown, MT 59457 Grand Master Jeffrey N. Nelson ..................... 4 Address changes or corrections La Forbie — The Beginning of the End and all membership activity for Frankish Outremer including deaths should be Sir Knight George L. Marshall, Jr., PGC ............. 7 reported to the recorder of the What’s the Point of a Sword? local Commandery. Please do Sir Knight John D. Barnes, PGC ...................... 12 not report them to the editor. Modern Day Chivalry Lawrence E. Tucker Sir Knight Thomas Hendrickson, PGM ........... 21 Grand Recorder Time To Move On Grand Encampment Office 5909 West Loop South, Suite 495 Reverend and Sir Knight J.B. Morris .............. 27 Bellaire, TX 77401-2402 Knights Templar Holy Land Pilgrimage Phone: (713) 349-8700 Fax: (713) 349-8710 for Sir Knights, their Ladies, and Friends ....... 30 E-mail: [email protected] Magazine materials and correspon- dence to the editor should be sent in elec- tronic form to the managing editor whose Features contact information is shown below. Materials and correspondence concern- Prelate’s Chapel ..................................................... 6 ing the Grand Commandery state supple- ments should be sent to the respective supplement editor. Focus on Chivalry .................................................. 14 John L. Palmer Leadership Notes - Delegating Effectively .............. 15 Managing Editor Post Office Box 566 The Knights Templar Eye Foundation ........5,16,17,20 Nolensville, TN 37135-0566 Phone: (615) 283-8477 Grand Commandery Supplement ......................... -

Medieval Mediterranean Influence in the Treasury of San Marco Claire

Circular Inspirations: Medieval Mediterranean Influence in the Treasury of San Marco Claire Rasmussen Thesis Submitted to the Department of Art For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. Introduction………………………...………………………………………….3 II. Myths……………………………………………………………………….....9 a. Historical Myths…………………………………………………………...9 b. Treasury Myths…………………………………………………………..28 III. Mediums and Materials………………………………………………………34 IV. Mergings……………………………………………………………………..38 a. Shared Taste……………………………………………………………...40 i. Global Networks…………………………………………………40 ii. Byzantine Influence……………………………………………...55 b. Unique Taste……………………………………………………………..60 V. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………...68 VI. Appendix………………………………………………………………….….73 VII. List of Figures………………………………………………………………..93 VIII. Works Cited…………………………………………………...……………104 3 I. Introduction In the Treasury of San Marco, there is an object of three parts (Figure 1). Its largest section piece of transparent crystal, carved into the shape of a grotto. Inside this temple is a metal figurine of Mary, her hands outstretched. At the bottom, the crystal grotto is fixed to a Byzantine crown decorated with enamels. Each part originated from a dramatically different time and place. The crystal was either carved in Imperial Rome prior to the fourth century or in 9th or 10th century Cairo at the time of the Fatimid dynasty. The figure of Mary is from thirteenth century Venice, and the votive crown is Byzantine, made by craftsmen in the 8th or 9th century. The object resembles a Frankenstein’s monster of a sculpture, an amalgamation of pieces fused together that were meant to used apart. But to call it a Frankenstein would be to suggest that the object’s parts are wildly mismatched and clumsily sewn together, and is to dismiss the beauty of the crystal grotto, for each of its individual components is finely made: the crystal is intricately carved, the figure of Mary elegant, and the crown vivid and colorful. -

The Seventh Crusade ST

ST. MARY THE VIRGIN Sovereign Military Order of the Temple of Jerusalem The Seventh Crusade ST. MARY THE VIRGIN The Seventh Crusade First Edition 2021 Prepared by Dr. Chev. Peter L. Heineman, GOTJ, CMTJ 2020 Avenue B Council Bluffs, IA 51501 Phone 712.323.3531• www.plheineman.net Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Historical Context ....................................................................................... 2 The Campaign ........................................................................................... 3 Cyprus ............................................................................................. 4 Damietta .......................................................................................... 4 Cairo ............................................................................................... 5 Battle of Monsourah ........................................................................ 5 Battle of Fariskur ............................................................................. 6 Aftermath ................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION Seventh Crusade he Seventh Crusade (1248-1254) was led by the French king Louis IX (r. 1226-1270) who intended to conquer Egypt and take over Jerusalem; both then controlled by the Muslim Ayyubid Dynasty. Despite the initial success of capturing Damietta on the Nile, Louis' troops were defeated by the T