Cilician Armenian Mediation in Crusader-Mongol Politics, C.1250-1350

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

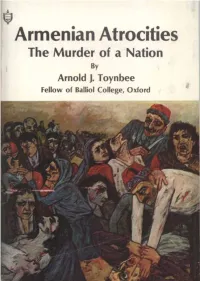

Armenian Atrocities the Murder of a Nation by Arnold J

Armenian Atrocities The Murder of a Nation By Arnold J. Toynbee Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford as . $315. R* f*4 p i,"'a p 7; mt & H ps4 & ‘ ' -it f, Armenian Atrocities: The Murder of a Nation By Arnold J. Toynbee Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford WITH A SPEECH DELIVERED BY LORD BRYCE IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS TANKIAN PUBLISHING CORPORATION -_NEW YORK MONTREAL LONDON Copyright © 1975 by Tankian Publishing Corp. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-10955 International Standard Book Number: 0-87899-005-4 First published in Great Britain by Hodder & Stoughton, 1917 First Tankian Publishing edition, 1975 Cover illustration: Original oil-painting by the renowned Franco-Armenian painter Zareh Mutafian, depicting the massacre of the Armenians by the Turks in 1915. TANKIAN TRADEMARK REG. U.S. PAT. OFF. AND FOREIGN COUNTRIES REGISTERED TRADEMARK - MARCA REGISTRADA PUBLISHED BY TANKIAN PUBLISHING CORP. G. P. O. BOX 678 -NEW YORK, N.Y. 10001 Printed in the United States of America DEDICATION 1915 - 1975 In commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the Armenian massacres by the Turks which commenced April 24, 1915, we dedicate the republication of this historical document to the memory of the almost 2,000,000 Armenian martyrs who perished during this great tragedy. A MAP displaying THE SCENE OF THE ATROCITIES P Boundaries of Regions thus =-:-- ‘\ s « summer RailtMys ThUS.... ...... .... |/i ; t 0 100 isouuts % «DAMAS CUQ BAGHDAQ - & Taterw A C*] \ C marked on this with the of twelve for such of the s Every place map, exception deported Armeninians as reached as them, as waiting- included in square brackets, has been the scene of either depor- places for death. -

The Conquest of Arsuf by Baybars: Political and Military Aspects (MSR IX.1, 2005)

REUVEN AMITAI THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY OF JERUSALEM The Conquest of Arsu≠f by Baybars: Political and Military Aspects* A modern-day visitor to Arsu≠f1 cannot help but be struck by the neatly arranged piles of stones from siege machines found at the site. This ordering, of course, represents the labors of contemporary archeologists and their assistants to gather the numerous but scattered stones. Yet, in spite of the recent nature of this "installation," these heaps are clear, if mute, evidence of the great efforts of the Mamluks led by Sultan Baybars (1260–77) to conquer the fortified city from the Franks in 1265. This conquest, as well as its political background and its aftermath, will be the subjects of the present article, which can also be seen as a case-study of Mamluk siege warfare. The immediate backdrop to the Mamluk attack against Arsu≠f was the events of the preceding weeks. At the end of 1264, while Baybars was hunting in the Egyptian countryside, he received reports that the Mongols were heading in force for the Mamluk border fortress of al-B|rah along the Euphrates, today in south- eastern Turkey. The sultan quickly returned to Cairo, and ordered the immediate dispatch of advanced light forces, which were followed by a more organized, but still relatively small, force under the command of the senior amir (officer) Ughan Samm al-Mawt ("the Elixir of Death"), and then by a third corps, together with © Middle East Documentation Center. The University of Chicago. *I would like to thank Prof. Israel Roll of Tel Aviv University, who conducted the excavations at the site, and was most helpful when he showed us the site. -

Was There a Custom of Distributing the Booty in the Crusades of the Thirteenth Century?

Benjámin Borbás WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? MA Thesis in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies Central European University Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2019 WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, -

Politik Penguasaan Bangsa Mongol Terhadap Negeri- Negeri Muslim Pada Masa Dinasti Ilkhan (1260-1343)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-Jurnal UIN (Universitas Islam Negeri) Alauddin Makassar Politik Penguasaan Bangsa Mongol Budi dan Nita (1260-1343) POLITIK PENGUASAAN BANGSA MONGOL TERHADAP NEGERI- NEGERI MUSLIM PADA MASA DINASTI ILKHAN (1260-1343) Budi Sujati dan Nita Yuli Astuti Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Gunung Djati Bandung Email: [email protected] Abstract In the history of Islam, the destruction of the Abbasid dynasty as the center of Islamic civilization in its time that occurred on February 10, 1258 by Mongol attacks caused Islam to lose its identity.The destruction had a tremendous impact whose influence could still be felt up to now, because at that time all the evidence of Islamic relics was destroyed and burnt down without the slightest left.But that does not mean that with the destruction of Islam as a conquered religion is lost as swallowed by the earth. It is precisely with Islam that the Mongol conquerors who finally after assimilated for a long time were drawn to the end of some of the Mongol descendants themselves embraced Islam by establishing the Ilkhaniyah dynasty based in Tabriz Persia (present Iran).This is certainly the author interest in describing a unique event that the rulers themselves who ultimately follow the beliefs held by the community is different from the conquests of a nation against othernations.In this study using historical method (historical study) which is descriptive-analytical approach by using as a medium in analyzing. So that events that have happened can be known by involving various scientific methods by using social science and humanities as an approach..By using social science and humanities will be able to answer events that happened to the Mongols as rulers over the Muslim world make Islam as the official religion of his government to their grandchildren. -

History of the Crusades. Episode 103 the Last Crusades. Hello Again

History of the Crusades. Episode 103 The Last Crusades. Hello again. Last week, things didn't go so well for the Latin Christians in the Middle East, with an entire Crusader state, the Principality of Antioch, being effectively wiped off the map following an invasion by the Egyptian Mamluk Sultan Baibars. The Latin Christians of Europe had been viewing events in the Holy Land with concern for some time, and with the fall of Antioch, it was obvious that some urgent assistance was required. More specifically, what was needed of course, was another Crusade. As far back as August 1266 Pope Clement IV had begun to call for a new Crusade. England had been wracked by civil war, but that had come to an end in 1265, and with King Louis IX’s ambitious brother Charles of Anjou securing for himself the Sicilian crown in 1266, the attentions of the people in Europe could finally focus on problems in the Middle East. King Louis of France, now aged in his early fifties, jumped at the chance to redeem the failure of his ill-fated previous Crusade, and on the 25th of March 1267 once again made a public vow to take up the Cross. Also raising their hands to mount a Crusade were Lord Edward of England and King James I of Aragon. Lord Edward was the son of the aging King Henry III of England, and would later become King Edward I. Against his father's wishes. Lord Edward made his Crusading vow in 1268, and many of the noblemen of England, keen to put the trauma of the recent civil war behind them, followed his example. -

In Search of Armenian Nobility: Five Armenian Families of the Ottoman Empire

J. Soc. for Armenian Stud. 3 (1987) Printed in the United States of America 93 Robert H. Hewsen IN SEARCH OF ARMENIAN NOBILITY: FIVE ARMENIAN FAMILIES OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE The importance of the nobility in Armenia before the loss of its independence cannot be overestimated, but the history of this nobility was characterized by a steady decline in the number of families of which it was composed. From about fifty in the fourth century A.D., the number of Armenian princely houses steadily dwindled to some forty-two in the fifth century, to thirty-five in the sixth, and to twenty in the eighth.1 Ultimately, only seven Armenian noble families are known for certain to have survived the fall of the last Armenian monarchy in 1375.2 Of these, five continued to exist in Georgia3 while three others, the House of Artsruni, the House of Siwni, and the House of Orbelian, survived on Armenian soil, the first until the Turkish occupation of Van; the remaining two under Persian and, later Russian rule.4 For all this, however, there are not lacking some Armenian fam- ilies of the Ottoman Empire who claim descent from the princely houses of the Armenia of old, and some of these families have played a conspicuous role in modern Armenian history. The basic problem in dealing with their claims lies in proving their legitimacy on grounds other than those of the family's own traditions, which valid though they may possibly be, by their very nature cannot always be verified. In the egalitarian world of Islam, and especially in the Ottoman Em- pire (which, unlike Russia, recognized no hereditary nobility beyond the imperial house itself), the lack of official recognition of nobiliary descent leaves us with very little support for nobiliary claims. -

Protagonist of Qubilai Khan's Unsuccessful

BUQA CHĪNGSĀNG: PROTAGONIST OF QUBILAI KHAN’S UNSUCCESSFUL COUP ATTEMPT AGAINST THE HÜLEGÜID DYNASTY MUSTAFA UYAR* It is generally accepted that the dissolution of the Mongol Empire began in 1259, following the death of Möngke the Great Khan (1251–59)1. Fierce conflicts were to arise between the khan candidates for the empty throne of the Great Khanate. Qubilai (1260–94), the brother of Möngke in China, was declared Great Khan on 5 May 1260 in the emergency qurultai assembled in K’ai-p’ing, which is quite far from Qara-Qorum, the principal capital of Mongolia2. This event started the conflicts within the Mongolian Khanate. The first person to object to the election of the Great Khan was his younger brother Ariq Böke (1259–64), another son of Qubilai’s mother Sorqoqtani Beki. Being Möngke’s brother, just as Qubilai was, he saw himself as the real owner of the Great Khanate, since he was the ruler of Qara-Qorum, the main capital of the Mongol Khanate. Shortly after Qubilai was declared Khan, Ariq Böke was also declared Great Khan in June of the same year3. Now something unprecedented happened: there were two competing Great Khans present in the Mongol Empire, and both received support from different parts of the family of the empire. The four Mongol khanates, which should theo- retically have owed obedience to the Great Khan, began to act completely in their own interests: the Khan of the Golden Horde, Barka (1257–66) supported Böke. * Assoc. Prof., Ankara University, Faculty of Languages, History and Geography, Department of History, Ankara/TURKEY, [email protected] 1 For further information on the dissolution of the Mongol Empire, see D. -

Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi POWER, POLITICS, AND TRADITION IN THE MONGOL EMPIRE AND THE ĪlkhānaTE OF IRAN OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Īlkhānate of Iran MICHAEL HOPE 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6D P, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Michael Hope 2016 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2016932271 ISBN 978–0–19–876859–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Il-Khanate Empire

1 Il-Khanate Empire 1250s, after the new Great Khan, Möngke (r.1251–1259), sent his brother Hülegü to MICHAL BIRAN expand Mongol territories into western Asia, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel primarily against the Assassins, an extreme Isma‘ilite-Shi‘ite sect specializing in political The Il-Khanate was a Mongol state that ruled murder, and the Abbasid Caliphate. Hülegü in Western Asia c.1256–1335. It was known left Mongolia in 1253. In 1256, he defeated to the Mongols as ulus Hülegü, the people the Assassins at Alamut, next to the Caspian or state of Hülegü (1218–1265), the dynasty’s Sea, adding to his retinue Nasir al-Din al- founder and grandson of Chinggis Khan Tusi, one of the greatest polymaths of the (Genghis Khan). Centered in Iran and Muslim world, who became his astrologer Azerbaijan but ruling also over Iraq, Turkme- and trusted advisor. In 1258, with the help nistan, and parts of Afghanistan, Anatolia, of various Mongol tributaries, including and the southern Caucasus (Georgia, many Muslims, he brutally conquered Bagh- Armenia), the Il-Khanate was a highly cos- dad, eliminating the Abbasid Caliphate that mopolitan empire that had close connections had nominally led the Muslim world for more with China and Western Europe. It also had a than 500 years (750–1258). Hülegü continued composite administration and legacy that into Syria, but withdrew most of his troops combined Mongol, Iranian, and Muslim after hearing of Möngke’s death (1259). The elements, and produced some outstanding defeat of the remnants of his troops by the cultural achievements. -

Port Cities and Printers: Reflections on Early Modern Global Armenian

Rqtv"Ekvkgu"cpf"Rtkpvgtu<"Tghngevkqpu"qp"Gctn{"Oqfgtp Inqdcn"Ctogpkcp"Rtkpv"Ewnvwtg Sebouh D. Aslanian Book History, Volume 17, 2014, pp. 51-93 (Article) Rwdnkujgf"d{"Vjg"Lqjpu"Jqrmkpu"Wpkxgtukv{"Rtguu DOI: 10.1353/bh.2014.0007 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/bh/summary/v017/17.aslanian.html Access provided by UCLA Library (24 Oct 2014 19:07 GMT) Port Cities and Printers Reflections on Early Modern Global Armenian Print Culture Sebouh D. Aslanian Since the publication of Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin’s L’aparition du livre in 1958 and more recently Elizabeth Eisenstein’s The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (1979), a substantial corpus of scholarship has emerged on print culture, and even a new discipline known as l’histoire du livre, or history of the book, has taken shape.1 As several scholars have al- ready remarked, the bulk of the literature on book history and the history of print has been overwhelmingly Eurocentric in conception. In her magnum opus, for instance, Eisenstein hardly pauses to consider whether some of her bold arguments on the “printing revolution” are at all relevant for the world outside Europe, except perhaps for Euroamerica. As one scholar has noted, “until recently, the available literature on the non-European cases has been very patchy.”2 The recent publication of Jonathan Bloom’s Paper Before Print (2001),3 Mary Elizabeth Berry’s Japan in Print (2007), Nile Green’s essays on Persian print and his Bombay Islam,4 several essays and works in press on printing in South Asia5 and Ming-Qing China,6 and the convening of an important “Workshop on Print in a Global Context: Japan and the World”7 indicate, however, that the scholarship on print and book history is now prepared to embrace the “global turn” in historical studies. -

The Mongol City of Ghazaniyya: Destruction, Spatial Reconstruction, and Preservation of the Urban Heritage1

Atri Hatef Naiemi The Mongol City of Ghazaniyya: Destruction, Spatial Reconstruction, and Preservation of the Urban Heritage1 Hülegü Khan (r. 1256-1265), a grandson of Chinggis Khan, founded the Ilkhanate in Iran in 1256 as the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. Mongol campaigns in Iran in the thirteenth century caused extensive destruction in different aspects of the Iranians’ social life and built environment. However, the political stability after the arrival of Hülegü intensified the process of urban development. Along with the reconstruction of the cities that had been extensively destroyed during the Mongol attack, the Ilkhans founded a number of new settlements. Their architectural and urban projects were mostly conducted in the northwest of present-day Iran, with some exceptions, for instance the city of Khabushan in Khurasan which was largely rebuilt by Hülegü and the notables of his court.2 In western Iran, Hülegü firstly focused his attention on the reconstruction of Baghdad, but following the designation of Azerbaijan as the headquarters of the Mongols, his urban development activities extended to this region. Maragha was chosen as the first capital of the Mongols and the most 1 This article has been adapted from a lecture presented in November 2019 at the Aga Khan Program in MIT. The research for this project has been facilitated by fellowship held with the Aga Khan program of MIT. I would like to thank Professors Nasser Rabbat and James Wescoat for their hospitality during the four months I spent at MIT in 2019. 2 In addition to Hülegü, Ghazan Khan also erected magnificent buildings in Khabushan. -

Dumbarton Oaks

annual report 2017–2018 Research Library and Collection and Library Research Dumbarton Oaks dumbarton oaks • 2017–2018 Washington, DC Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection 2017–2018 Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Annual Report 2017–2018 © 2018 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC ISSN 0197-9159 Cover: The Cutting Garden Frontispiece: Albert Edward Sterner (American, 1863–1946). Mildred Barnes Bliss, 1908. Chalk (sanguine crayon), charcoal, and graphite on paper. HC.D.1908.03.(Cr) www.doaks.org/about/annual-reports Contents From the Director 7 Director’s Office 13 Academic Programs 19 Fellowship Reports 35 Byzantine Studies 57 Garden and Landscape Studies 69 Pre-Columbian Studies 81 Library 89 Publications and Digital Humanities 95 Museum 105 Garden 113 Music at Dumbarton Oaks 117 Facilities, Finance, Human Resources, and Information Technology 121 Administration and Staff 127 From the Director This is the tenth annual report to roll off the presses during my direc- torship, which began in 2007. Previously, Dumbarton Oaks dissemi- nated only bare lists of facts and figures without accompanying prose. The full run of such accounts, reaching back to 1989, can be inspected on the website. For a decade now, a different kind of compendium has been offered yearly: a historical record that doubles as a celebration of imaginative industry. If nothing else, I aim in this statement to voice the appreciation I feel for my colleagues at Dumbarton Oaks. Without their commitment and daily contributions, all dreams relating to aca- demic programs and physical plans would stay vaporous nothings. My collaborators in this wonderful establishment encompass dozens of extraordinarily experienced, talented, and creative individuals who not only come to work with a spring in their step but who, through their performance, put the same resilience into the strides of those they assist.