Port Cities and Printers: Reflections on Early Modern Global Armenian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

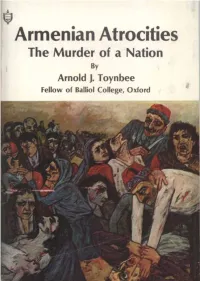

Armenian Atrocities the Murder of a Nation by Arnold J

Armenian Atrocities The Murder of a Nation By Arnold J. Toynbee Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford as . $315. R* f*4 p i,"'a p 7; mt & H ps4 & ‘ ' -it f, Armenian Atrocities: The Murder of a Nation By Arnold J. Toynbee Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford WITH A SPEECH DELIVERED BY LORD BRYCE IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS TANKIAN PUBLISHING CORPORATION -_NEW YORK MONTREAL LONDON Copyright © 1975 by Tankian Publishing Corp. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-10955 International Standard Book Number: 0-87899-005-4 First published in Great Britain by Hodder & Stoughton, 1917 First Tankian Publishing edition, 1975 Cover illustration: Original oil-painting by the renowned Franco-Armenian painter Zareh Mutafian, depicting the massacre of the Armenians by the Turks in 1915. TANKIAN TRADEMARK REG. U.S. PAT. OFF. AND FOREIGN COUNTRIES REGISTERED TRADEMARK - MARCA REGISTRADA PUBLISHED BY TANKIAN PUBLISHING CORP. G. P. O. BOX 678 -NEW YORK, N.Y. 10001 Printed in the United States of America DEDICATION 1915 - 1975 In commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the Armenian massacres by the Turks which commenced April 24, 1915, we dedicate the republication of this historical document to the memory of the almost 2,000,000 Armenian martyrs who perished during this great tragedy. A MAP displaying THE SCENE OF THE ATROCITIES P Boundaries of Regions thus =-:-- ‘\ s « summer RailtMys ThUS.... ...... .... |/i ; t 0 100 isouuts % «DAMAS CUQ BAGHDAQ - & Taterw A C*] \ C marked on this with the of twelve for such of the s Every place map, exception deported Armeninians as reached as them, as waiting- included in square brackets, has been the scene of either depor- places for death. -

Publications 1427998433.Pdf

THE CHURCH OF ARMENIA HISTORIOGRAPHY THEOLOGY ECCLESIOLOGY HISTORY ETHNOGRAPHY By Father Zaven Arzoumanian, PhD Columbia University Publication of the Western Diocese of the Armenian Church 2014 Cover painting by Hakob Gasparian 2 During the Pontificate of HIS HOLINESS KAREKIN II Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos of All Armenians By the Order of His Eminence ARCHBISHOP HOVNAN DERDERIAN Primate of the Western Diocese Of the Armenian Church of North America 3 To The Mgrublians And The Arzoumanians With Gratitude This publication sponsored by funds from family and friends on the occasion of the author’s birthday Special thanks to Yeretsgin Joyce Arzoumanian for her valuable assistance 4 To Archpriest Fr. Dr. Zaven Arzoumanian A merited Armenian clergyman Beloved Der Hayr, Your selfless pastoral service has become a beacon in the life of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Blessed are you for your sacrificial spirit and enduring love that you have so willfully offered for the betterment of the faithful community. You have shared the sacred vision of our Church fathers through your masterful and captivating writings. Your newest book titled “The Church of Armenia” offers the reader a complete historiographical, theological, ecclesiological, historical and ethnographical overview of the Armenian Apostolic Church. We pray to the Almighty God to grant you a long and a healthy life in order that you may continue to enrich the lives of the flock of Christ with renewed zeal and dedication. Prayerfully, Archbishop Hovnan Derderian Primate March 5, 2014 Burbank 5 PREFACE Specialized and diversified studies are included in this book from historiography to theology, and from ecclesiology to ethno- graphy, most of them little known to the public. -

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v ABSTRACT Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Yektan Turkyilmaz 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the conflict in Eastern Anatolia in the early 20th century and the memory politics around it. It shows how discourses of victimhood have been engines of grievance that power the politics of fear, hatred and competing, exclusionary -

2017 Newsletter

NEWSLETTER FALL 2017 Liminality & ISSUE 11 Memorial Practices IN 3 Notes from the Director THIS 4 Faculty News and Updates ISSUE: 6 Year in Review: Orphaned Fields: Picturing Armenian Landscapes Photography and Armenian Studies Orphans of the Armenian Genocide Eighth Annual International Graduate Student Workshop 11 Meet the Manoogian Fellows NOTES FROM 14 Literature and Liminality: Exploring the Armenian in-Between THE DIRECTOR Armenian Music, Memorial Practices and the Global in the 21st 14 Kathryn Babayan Century Welcome to the new academic year! 15 International Justice for Atrocity Crimes - Worth the Cost? Over the last decade, the Armenian represents the first time the Armenian ASP Faculty Armenian Childhood(s): Histories and Theories of Childhood and Youth Studies Program at U-M has fostered a Studies Program has presented these 16 Hakem Al-Rustom in American Studies critical dialogue with emerging scholars critical discussions in a monograph. around the globe through various Alex Manoogian Professor of Modern workshops, conferences, lectures, and This year we continue in the spirit of 16 Multidisciplinary Workshop for Armenian Studies Armenian History fellowships. Together with our faculty, engagement with neglected directions graduate students, visiting fellows, and in the field of Armenian Studies. Our Profiles and Reflections Kathryn Babayan 17 postdocs we have combined our efforts two Manoogian Post-doctoral fellows, ASP Fellowship Recipients Director, Armenian to push scholarship in Armenian Studies Maral Aktokmakyan and Christopher Studies Program; 2017-18 ASP Graduate Students in new directions. Our interventions in Sheklian, work in the fields of literature Associate Professor of the study of Armenian history, literature, and anthropology respectively. -

AIEA 4U3ququtunhunhu-Tubl-Nh [J-Hgug+U3[.T Etuqbf'uqsnhrùhhtu CJ Associattoninternationale DES Éruors Nnuérursnnes / J

# AIEA 4U3qUqUtunhunhu-tubl-nh [J-hgug+u3[.t etuqbf'uqSnhrùhhtu CJ ASSocIATToNINTERNATIoNALE DES Éruors nnuÉrurSNNES / J \r ^f CONTENTS Letterof CondolenceBy AIEA President on the Passingof AcademicianGagik Sarkissian Letter of Condolenceon the Passing August 27,1998 of Academician Gagik Sarkissian 1 AIEA Committee Elections - CnlI for Nominntiotts 2 - AIEA VIII. General ConferenceVienna 29.9 1.1,01999 2 Academician Faddei Sarkissian, President, LoIa Koundakjian and Leaon Audoyan AIEA NezusletterEditors Nationai Academy of Sciencesof Armenia Note on Editorial Addressesand the AIEA Library Barekamutyun 24, Narekatsi Chair in Armenian Studies Yerevan UCLA Searchfor htccessor to Aaedis K. Sanjian Sixth International Conferenceof Armenian Linguistics, Paris luly 5-9, 1999 4 Seminaire lnterdisciplinaire de la Sociétédes Etudes Arméniennes 5 1"999Armenian Language Summer lnstitute in Ereaan 6 Dear Academician Sarkissian, Philantropist SurenD. Fesjian Makes Donation to HebrezuUnioersity of lerusalem Armenian Studies Program 7 It was with profound sorrow that I received a message from Prof. TzooHitherto Unnoticed Armenian Gospels in Chillicothe, Ohio? 8 N. Hovhanissian bearing the dire news of Gagik Sarkissian's passing. Morgan Library Acquires Armenian Manuscript zuith Rare Siloer Binding The loss for you and the academic world of Armenia is most immediate, but Gagik was much beloved and respected the world Morgan Library Acquisition of llluminated Leaf of over, in circles both of Armenologists and Assyriologists. He was a scholar Marshal Oshin Gospel 10 of great international reputation, and his warm and energetic Morgan Library Publication of Syposium Papers personality contributed greatly to the community of which he formed a "TreAstftes in HeAuen" 10 part. He will be sorely missed both as a man of learning and as a man VeniceMekhitarists Manuscript Catalogue VoIs 1--8Aaailable 1.1 of wisdom. -

The Torchbearer • }Ahagir St

The Torchbearer • }ahagir St. John Armenian Church of Greater Detroit 22001 Northwestern Highway • Southfield, MI 48075 248.569.3405 (phone) • 248.569.0716 (fax) • www.stjohnsarmenianchurch.org The Reverend Father Garabed Kochakian ~ Pastor The Reverend Father Diran Papazian ~ Pastor Emeritus Deacon Rubik Mailian ~ Director of Sacred Music and Pastoral Assistant In Memoriam: Archbishop Torkom Manoogian (1919-2012) With deep sorrow, the Eastern Diocese of the Armenian Church of America mourns the passing of His Beatitude Archbishop Torkom Manoogian, the 96th Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem, and the long- serving former Primate of our own Diocese. Patriarch Torkom entered his eternal rest on October 12, 2012, at age 93. He was interred in Jerusalem, at the Patriarchal Cemetery, on Monday, October 22. In 2012, he suffered a serious decline in health. In January he was admitted to a hospital in Jerusalem, and subsequently was cared for in the city’s Franciscan hospice, close by to the Armenian Patriarchate, where he was visited by friends and relatives. It was there that he fell asleep in the Lord. Prior to his election as Patriarch of Jerusalem, Archbishop Torkom served for a quarter-century as Primate of the Eastern Diocese. To thousands of people across this country-not only in our parishes, but in the surrounding society-he was the vigorous, compassionate, always impressive face of the Armenian Church of America. He was also the beautiful, poetic voice of our people, advocating in a principled and forceful way for our concerns and aspirations, while embodying the great Armenian civilization that had bestowed works of profound art and spirituality on world culture. -

Armenian Printers

The Armenian Weekly WWW.ARMENIANWEEKLY.COM SEPTEMBER 1, 2012 The Armenian Weekly SEPTEMBER 1, 2012 CONTENTS Contributors Armenian medieval Armenian Printing in 2 13 Historians in Print: 25America (1857–1912) 500 Years: A Celebration Three Centuries of —By Teotig, 3 of Ink and Paper and Glue Scholarship across Translated and Edited —By Chris Bohjalian Three Continents by Vartan Matiossian —By Ara Sanjian Talk to Me A World History 5 —By Kristi Rendahl Celebrating 500 Years 28of Armenian Printers of Armenian Printing —By Artsvi “Wings on Their Feet and 22 —By Lilly Torosyan Bakhchinyan 7 on their Heads: Reflections on Port Armenians and The First Historian of Five Centuries of Global 24Armenian Printing Armenian Print Culture” —By Vartan Matiossian —By Sebouh D. Aslanian Editor: Khatchig Mouradian The Armenian Weekly Copy-editor: Nayiri Arzoumanian CONTRIBUTORS Art Director: Gina Poirier Sebouh David Aslanian was born in Ethiopia and Born in Montevideo (Uruguay) and long-time resi- received his Ph.D. (with distinction) from Columbia dent of Buenos Aires (Argentina), Dr. Vartan University in 2007. He holds the Richard Hovannisian Matiossian is a historian, literary scholar, translator Endowed Chair of Modern Armenian history at the and educator living in New Jersey. He has published department of history at UCLA. His recently published six books on Armenian history and literature. He is From the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean: The currently the executive director of the Armenian Global Trade Networks of Armenian Merchants from New Julfa National Education Committee in New York and book review editor (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011) was the recipient of of Armenian Review. -

Cilician Armenian Mediation in Crusader-Mongol Politics, C.1250-1350

HAYTON OF KORYKOS AND LA FLOR DES ESTOIRES: CILICIAN ARMENIAN MEDIATION IN CRUSADER-MONGOL POLITICS, C.1250-1350 by Roubina Shnorhokian A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (January, 2015) Copyright ©Roubina Shnorhokian, 2015 Abstract Hayton’s La Flor des estoires de la terre d’Orient (1307) is typically viewed by scholars as a propagandistic piece of literature, which focuses on promoting the Ilkhanid Mongols as suitable allies for a western crusade. Written at the court of Pope Clement V in Poitiers in 1307, Hayton, a Cilician Armenian prince and diplomat, was well-versed in the diplomatic exchanges between the papacy and the Ilkhanate. This dissertation will explore his complex interests in Avignon, where he served as a political and cultural intermediary, using historical narrative, geography and military expertise to persuade and inform his Latin audience of the advantages of allying with the Mongols and sending aid to Cilician Armenia. This study will pay close attention to the ways in which his worldview as a Cilician Armenian informed his perceptions. By looking at a variety of sources from Armenian, Latin, Eastern Christian, and Arab traditions, this study will show that his knowledge was drawn extensively from his inter-cultural exchanges within the Mongol Empire and Cilician Armenia’s position as a medieval crossroads. The study of his career reflects the range of contacts of the Eurasian world. ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the financial support of SSHRC, the Marjorie McLean Oliver Graduate Scholarship, OGS, and Queen’s University. -

The Armenians from Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars

The Armenians From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars RAZMIK PANOSSIAN HURST & COMPANY, LONDON THE ARMENIANS To my parents Stephan and Sona Panossian RAZMIK PANOSSIAN The Armenians From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars HURST & COMPANY,LONDON First published in the United Kingdom by C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd, 41 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3PL Copyright © by Razmik Panossian, 2006 All rights reserved. Printed in India The right of Razmik Panossian to be identified as the author of this volume has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyight, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. A catalogue record for this volume is available from the British Library. ISBNs 1-85065-644-4 casebound 1-85065-788-2 paperback ‘The life of a nation is a sea, and those who look at it from the shore cannot know its depths.’—Armenian proverb ‘The man who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign land. The tender soul has fixed his love on one spot in the world; the strong man has extended his love to all places; the perfect man has extinguished his.’—Hugo of St Victor (monk from Saxony,12th century) The proverb is from Mary Matossian, The Impact of Soviet Policies in Armenia. Hugo of St Victor is cited in Edward Said, ‘Reflections on Exile’, Granta, no. 13. CONTENTS Preface and Acknowledgements page xi 1. Introduction 1 THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND DEFINITIONS 5 A brief overview: going beyond dichotomies 6 Questionable assumptions: homogenisation and the role of the state 10 The Armenian view 12 Defining the nation 18 — The importance of subjectivity 20 — The importance of modernity 24 — The characteristics of nations 28 2. -

L'arte Armena. Storia Critica E Nuove Prospettive Studies in Armenian

e-ISSN 2610-9433 THE ARMENIAN ART ARMENIAN THE Eurasiatica ISSN 2610-8879 Quaderni di studi su Balcani, Anatolia, Iran, Caucaso e Asia Centrale 16 — L’arte armena. Storia critica RUFFILLI, SPAMPINATO RUFFILLI, FERRARI, RICCIONI, e nuove prospettive Studies in Armenian and Eastern Christian Art 2020 a cura di Edizioni Aldo Ferrari, Stefano Riccioni, Ca’Foscari Marco Ruffilli, Beatrice Spampinato L’arte armena. Storia critica e nuove prospettive Eurasiatica Serie diretta da Aldo Ferrari, Stefano Riccioni 16 Eurasiatica Quaderni di studi su Balcani, Anatolia, Iran, Caucaso e Asia Centrale Direzione scientifica Aldo Ferrari (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Stefano Riccioni (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Comitato scientifico Michele Bacci (Universität Freiburg, Schweiz) Giampiero Bellingeri (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Levon Chookaszian (Yerevan State University, Armenia) Patrick Donabédian (Université d’Aix-Marseille, CNRS UMR 7298, France) Valeria Fiorani Piacentini (Università Cattolica del Sa- cro Cuore, Milano, Italia) Ivan Foletti (Masarikova Univerzita, Brno, Česká republika) Gianfranco Giraudo (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Annette Hoffmann (Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, Deutschland) Christina Maranci (Tuft University, Medford, MA, USA) Aleksander Nau- mow (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Antonio Panaino (Alma Mater Studiorum, Università di Bologna, Italia) Antonio Rigo (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Adriano Rossi (Università degli Studi di Napoli «L’Orientale», Italia) -

Area Studies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 091 303 SO 007 520 AUTHOR Stone, Frank A. TITLE Armenian Studies for Secondary Students, A Curriculum Guide. INSTITUTION Connecticut Univ., Storrs. World Education Project. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 55p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$3 15 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibographies; *Area Studies; Cultural Pluralism; *Culture; *Ethnic Studies; Evaluation; *Humanities; Immigrants; Instructional Materials; Interdisciplinary Approach; *Middle Eastern Studies; Minority Groups; Questioning Techniques; Resource Materials; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS Armenians; *World Education Project ABSTRACT The guide outlines a two to six week course of study on Armenian history and culture for secondary level students. The unit will help students develop an understanding of the following: culture of the American citizens of Armenian origin; key events and major trends in Armenian history; Armenian architecture, folklore, literature and music as vehicles of culture; and characteristics of Armenian educational, political and religious institutions. Teaching strategies suggested include the use of print and non-print materials, questioning techniques, classroom discussion, art activities, field traps, and classroom visits by Armenian-Americans. The guide consists c)i the following seven units:(1) The Armenians in North America; (2) sk.,,tches of Armenian History;(3) Armenian Mythology; (4) lic)ices of Fiction and Poetry;(5) Armenian Christianity; (e) Armenian Fine Arts; and (7)Armenian Political Aims. InstrLF-ional and resource materials, background sources, teaching s...7atc,c !s, and questions to stimulate classroom discussion are prove.': :'fc,r each unit. (Author/RM) U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NO1 NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFF ICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY ARMENIAN STUDIES FOR SECONDARY STUDENTS P% A Curriculum Guide Prepared by Frank A. -

1 | 1 0 the PRINTING ENTERPRISE of ARMENIANS in INDIA for A

THE PRINTING ENTERPRISE OF ARMENIANS IN INDIA For a long time, the Armenian books published in India were little known or studied, largely because of their normal print-runs of only 100-200 copies and their very limited circulation outside of India. The only extensive research in that field was conducted by H. Irazek (Hagob Ter Hagobian), who in the 1930’s had the unique opportunity to work at the Library of All Savior’s Monastery in New Julfa, which had the largest collection of Armenian publications from India. His History of Armenian Printing in India, was published in Antelias, in 1986. The Armenian printing enterprise in India that started in Madras and continued in Calcutta, lasted for a century and produced almost 200 books and booklets and 13 periodicals through 12 different printing presses. Today, within the time limits set for this conference, I will only try to present the highlights of Armenian printing in India. Since the late 17th century, close cooperation developed between the British East India Company and Armenian merchants of New Julfa origin, who enjoyed special privileges in trade and civil matters in Madras, Calcutta and Bombay, all of which were under British control. But by the late 1760’s, the British had changed their policy by restricting the trade operations of Armenians. These developments coincided with the arrival of Joseph Emin in Madras, after 19 years of travel and “adventures” for the liberation of Armenia. In Madras he tried but failed to secure financial support from the Armenian merchants for his liberation plans. But certainly he made an impact on a small circle of merchants, chief among them being Shahamir Shahamirian.