Michael Brooks Dissertation Graduate School Submission Revised 12-10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armenian Atrocities the Murder of a Nation by Arnold J

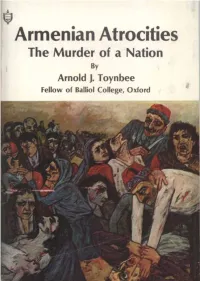

Armenian Atrocities The Murder of a Nation By Arnold J. Toynbee Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford as . $315. R* f*4 p i,"'a p 7; mt & H ps4 & ‘ ' -it f, Armenian Atrocities: The Murder of a Nation By Arnold J. Toynbee Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford WITH A SPEECH DELIVERED BY LORD BRYCE IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS TANKIAN PUBLISHING CORPORATION -_NEW YORK MONTREAL LONDON Copyright © 1975 by Tankian Publishing Corp. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-10955 International Standard Book Number: 0-87899-005-4 First published in Great Britain by Hodder & Stoughton, 1917 First Tankian Publishing edition, 1975 Cover illustration: Original oil-painting by the renowned Franco-Armenian painter Zareh Mutafian, depicting the massacre of the Armenians by the Turks in 1915. TANKIAN TRADEMARK REG. U.S. PAT. OFF. AND FOREIGN COUNTRIES REGISTERED TRADEMARK - MARCA REGISTRADA PUBLISHED BY TANKIAN PUBLISHING CORP. G. P. O. BOX 678 -NEW YORK, N.Y. 10001 Printed in the United States of America DEDICATION 1915 - 1975 In commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the Armenian massacres by the Turks which commenced April 24, 1915, we dedicate the republication of this historical document to the memory of the almost 2,000,000 Armenian martyrs who perished during this great tragedy. A MAP displaying THE SCENE OF THE ATROCITIES P Boundaries of Regions thus =-:-- ‘\ s « summer RailtMys ThUS.... ...... .... |/i ; t 0 100 isouuts % «DAMAS CUQ BAGHDAQ - & Taterw A C*] \ C marked on this with the of twelve for such of the s Every place map, exception deported Armeninians as reached as them, as waiting- included in square brackets, has been the scene of either depor- places for death. -

Local History of Ethiopia an - Arfits © Bernhard Lindahl (2005)

Local History of Ethiopia An - Arfits © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) an (Som) I, me; aan (Som) milk; damer, dameer (Som) donkey JDD19 An Damer (area) 08/43 [WO] Ana, name of a group of Oromo known in the 17th century; ana (O) patrikin, relatives on father's side; dadi (O) 1. patience; 2. chances for success; daddi (western O) porcupine, Hystrix cristata JBS56 Ana Dadis (area) 04/43 [WO] anaale: aana eela (O) overseer of a well JEP98 Anaale (waterhole) 13/41 [MS WO] anab (Arabic) grape HEM71 Anaba Behistan 12°28'/39°26' 2700 m 12/39 [Gz] ?? Anabe (Zigba forest in southern Wello) ../.. [20] "In southern Wello, there are still a few areas where indigenous trees survive in pockets of remaining forests. -- A highlight of our trip was a visit to Anabe, one of the few forests of Podocarpus, locally known as Zegba, remaining in southern Wello. -- Professor Bahru notes that Anabe was 'discovered' relatively recently, in 1978, when a forester was looking for a nursery site. In imperial days the area fell under the category of balabbat land before it was converted into a madbet of the Crown Prince. After its 'discovery' it was declared a protected forest. Anabe is some 30 kms to the west of the town of Gerba, which is on the Kombolcha-Bati road. Until recently the rough road from Gerba was completed only up to the market town of Adame, from which it took three hours' walk to the forest. A road built by local people -- with European Union funding now makes the forest accessible in a four-wheel drive vehicle. -

The Golden Gospels and Chronicle of Aksum at Aksum Seyon’S Church: the Photographs Taken by Theodor V

The Golden Gospels and Chronicle of Aksum at Aksum Seyon’s Church: The photographs taken by Theodor v. Lüpke (1906) Anaïs Wion To cite this version: Anaïs Wion. The Golden Gospels and Chronicle of Aksum at Aksum Seyon’s Church: The pho- tographs taken by Theodor v. Lüpke (1906). Steffen Wenig. IN KAISERLICHEM AUFTRAG. Die Deutsche Aksum-Expedition 1906 unter Enno Littmann, Ethnographische, kirchenhistorische und archäologisch-historische Untersuchungen (3), Reichert Verlag, pp.117-133, 2017, 978-3-89500-891-7. halshs-01525075 HAL Id: halshs-01525075 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01525075 Submitted on 21 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Anaïs Wion The Golden Gospels and Chronicle of Aksum at Aksum Seyon’s Church: The photographs taken by Theodor v. Lüpke (1906)* Enno Littmann had a great interest in Ethio- the DAE took photographs closer up of regalia pian literature, both written and oral: while from the church, including the codices (Figs. 2 in Ethiopia, he collected 149 codices and 167 and 3).4 The next day, Littmann and v. Lüpke scrolls and he also transcribed and translated returned to the church and asked for permission numerous oral traditions.1 In parallel, members to take pictures of the two Golden Gospels and of the DAE – especially Theodor v. -

The 'Van Dyke' Mango

7. MofTet, M. L. 1973. Bacterial spot of stone fruit in Queensland. 12. Sherman, W. B., C. E. Yonce, W. R. Okie, and T. G. Beckman. Australian J. Biol. Sci. 26:171-179. 1989. Paradoxes surrounding our understanding of plum leaf scald. 8. Sherman, W. B. and P. M. Lyrene. 1985. Progress in low-chill plum Fruit Var. J. 43:147-151. breeding. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 98:164-165. 13. Topp, B. L. and W. B. Sherman. 1989. Location influences on fruit 9. Sherman, W. B. and J. Rodriquez-Alcazar. 1987. Breeding of low- traits of low-chill peaches in Australia. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. chill peach and nectarine for mild winters. HortScience 22:1233- 102:195-199. 1236. 14. Topp, B. L. and W. B. Sherman. 1989. The relationship between 10. Sherman, W. B. and R. H. Sharpe. 1970. Breeding plums in Florida. temperature and bloom-to-ripening period in low-chill peach. Fruit Fruit Var. Hort. Dig. 24:3-4. Var.J. 43:155-158. 11. Sherman, W. B. and B. L. Topp. 1990. Peaches do it with chill units. Fruit South 10(3): 15-16. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 103:298-299. 1990. THE 'VAN DYKE' MANGO Carl W. Campbell History University of Florida, I FAS Tropical Research and Education Center The earliest records we were able to find on the 'Van Homestead, FL 33031 Dyke' mango were in the files of the Variety Committee of the Florida Mango Forum. They contain the original de scription form, quality evaluations dated June and July, Craig A. -

Volume 4 Issue 4 September 2020 Many of You May Have Heard the About Renewing for Another Year

The Little Rose Newsletter The Voice of the Rose Ferron Foundation of Rhode Island Volume 4 Issue 4 September 2020 Many of you may have heard the about renewing for another year. For saying: “There’s a crack in everything, those of you who may have joined in that is how the light gets in.” This is a a month other than September, we line written by Leonard Cohen. will send out reminders via e-mail. Reflecting on this line, as one having a Membership not only supports our devotion to Little Rose, we begin to work but more importantly shows understand what Little Rose and the that there is still a strong devotion to year 2020 had in common. They both “Little Rose” and a need to keep her began in a healthy good way and then memory alive. both were shattered by a sickness that In whatever way our world has entered in. Sickness being the “crack” shifted through these challenging in both. times, we must, as Little Rose did in In our dealings with this change in imitation of, and in union with Jesus, our world, we have sadly decided to embrace what we have to suffer and cancel our fundraiser for this year. in this way God can and will channel We are thinking of different fundrais- the focus on another membership His light in order to fill all our broken ing avenues which we will share in the drive. If you joined as a yearly mem- places with His grace. future. For now we will try to keep ber last September, it is time to think We will persevere and overcome present difficulties. -

Profile of a Plant: the Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE By

Profile of a Plant: The Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE by Benjamin Jon Graham A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paolo Squatriti, Chair Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes Professor Richard P. Tucker Professor Raymond H. Van Dam © Benjamin J. Graham, 2014 Acknowledgements Planting an olive tree is an act of faith. A cultivator must patiently protect, water, and till the soil around the plant for fifteen years before it begins to bear fruit. Though this dissertation is not nearly as useful or palatable as the olive’s pressed fruits, its slow growth to completion resembles the tree in as much as it was the patient and diligent kindness of my friends, mentors, and family that enabled me to finish the project. Mercifully it took fewer than fifteen years. My deepest thanks go to Paolo Squatriti, who provoked and inspired me to write an unconventional dissertation. I am unable to articulate the ways he has influenced my scholarship, teaching, and life. Ray Van Dam’s clarity of thought helped to shape and rein in my run-away ideas. Diane Hughes unfailingly saw the big picture—how the story of the olive connected to different strands of history. These three people in particular made graduate school a humane and deeply edifying experience. Joining them for the dissertation defense was Richard Tucker, whose capacious understanding of the history of the environment improved this work immensely. In addition to these, I would like to thank David Akin, Hussein Fancy, Tom Green, Alison Cornish, Kathleen King, Lorna Alstetter, Diana Denney, Terre Fisher, Liz Kamali, Jon Farr, Yanay Israeli, and Noah Blan, all at the University of Michigan, for their benevolence. -

Eco and Popular Culture Norma Bouchard

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85209-8 - New Essays on Umberto Eco Edited by Peter Bondanella Excerpt More information chapter 1 Eco and popular culture Norma Bouchard Since the beginning of his long and most distinguished career, Umberto Eco has demonstrated an equal devotion to the high canon of Western literature and to popular, mass-produced and mass-consumed, artifacts. Within Eco’s large corpus of published works, however, it is possible to chart different as well as evolving evaluations of the aesthetic merit of both popular and high cultural artifacts. Because such evaluations belong to a corpus that spans from the 1950s to the present, they necessarily reflect the larger epistemological changes that ensued when the resistance to commercialized mass culture on the part of an elitist, aristocratic strand of modern art theory gave way to a postmodernist blurring of the divide between different types of discourses. Yet, it is also crucial to remem- ber that, from his earlier publications onwards, Eco has approached the cultural field as a vast domain of symbolic production where high- and lowbrow arts not only coexist, but also are both complementary and sometimes interchangeable. This holistic understanding of the cultural field explains Eco’s earlier praise of selected popular works amidst a pleth- ora of negative evaluations, as well as his later fictional practice of cita- tions and replays that shapes his work as best-selling novelist of The Name of the Rose (1980), followed by Foucault’s Pendulum (1988), The Island of the Day Before (1994), Baudolino (2000), and The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana (2004). -

The Cathedral Priory of St. Andrew, Rochester

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society THE CATHEDRAL PRIORY OF ST. ANDREW, ROCHESTER By ANNE M. OAKLEY, M.A. THE church of St. Andrew the Apostle, Rochester, was founded by Ethelbert, King of Kent, as a college for a small number of secular canons under Justus, Bishop of Rochester, in A.D. 604. Very httle is known about the history of this house. It never seems to have had much influence outside its own walls, and though it possessed considerable landed estates, seems to have been relatively small and poor. It also suffered at the hands of the Danes. Bishops Justus, Romanus, Pauhnus and Ithamar were all remarkable men, but after Bishop Putta's transla- tion to Hereford in 676, very Httle is heard of Rochester. Their bishop, Siweard, is not mentioned as having been at Hastings with King Harold as were many of the Saxon bishops and abbots, and the house put up no opposition to William I when he seized their lands and gave them to his half brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, whom he had created Earl of Kent. The chroniclers say that the house was destitute, and that, when Siweard died in 1075, it was barely able to support the five canons on the estabHshment.1 Four years after his conquest of England, Wilham I invited his friend Lanfranc, Prior of Caen and a former monk of Bee in Normandy, to be bis archbishop at Canterbury. Lanfranc's task was specific: to reorganize EngHsh monasticism on the pattern of Bee; to develop a strict cloistered monasticism, but one of a kind that was not entirely cut off by physical barriers from the Hfe of the rest of the church. -

Road Map for Developing & Strengthening The

KENYA ROAD MAP FOR DEVELOPING & STRENGTHENING THE PROCESSED MANGO SECTOR DECEMBER 2014 TRADE IMPACT FOR GOOD The designations employed and the presentation of material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Trade Centre concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This document has not formally been edited by the International Trade Centre. ROAD MAP FOR DEVELOPING & STRENGTHENING THE KENYAN PROCESSED MANGO SECTOR Prepared for International Trade Centre Geneva, december 2014 ii This value chain roadmap was developed on the basis of technical assistance of the International Trade Centre ( ITC ). Views expressed herein are those of consultants and do not necessarily coincide with those of ITC, UN or WTO. Mention of firms, products and product brands does not imply the endorsement of ITC. This document has not been formally edited my ITC. The International Trade Centre ( ITC ) is the joint agency of the World Trade Organisation and the United Nations. Digital images on cover : © shutterstock Street address : ITC, 54-56, rue de Montbrillant, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Postal address : ITC Palais des Nations 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Telephone : + 41- 22 730 0111 Postal address : ITC, Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Email : [email protected] Internet : http :// www.intracen.org iii ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS Unless otherwise specified, all references to dollars ( $ ) are to United States dollars, and all references to tons are to metric tons. The following abbreviations are used : AIJN European Fruit Juice Association BRC British Retail Consortium CPB Community Business Plan DC Developing countries EFTA European Free Trade Association EPC Export Promotion Council EU European Union FPEAK Fresh Produce Exporters Association of Kenya FT Fairtrade G.A.P. -

Barly Records on Bantu Arvi Hurskainen

Remota Relata Srudia Orientalia 97, Helsinki 20O3,pp.65-76 Barly Records on Bantu Arvi Hurskainen This article gives a short outline of the early, sometimes controversial, records of Bantu peoples and languages. While the term Bantu has been in use since the mid lgth century, the earliest attempts at describing a Bantu language were made in the lTth century. However, extensive description of the individual Bantu languages started only in the l9th century @oke l96lab; Doke 1967; Wolff 1981: 2l). Scholars have made great efforts in trying to trace the earliest record of the peoples currently known as Bantu. What is considered as proven with considerable certainty is that the first person who brought the term Bantu to the knowledge of scholars of Africa was W. H. L Bleek. When precisely this happened is not fully clear. The year given is sometimes 1856, when he published The lnnguages of Mosambique, oÍ 1869, which is the year of publication of his unfinished, yet great work A Comparative Grammar of South African Languages.In The Languages of Mosambiqu¿ he writes: <<The languages of these vocabularies all belong to that great family which, with the exception of the Hottentot dialects, includes the whole of South Africa, and most of the tongues of Western Africa>. However, in this context he does not mention the name of the language family concemed. Silverstein (1968) pointed out that the first year when the word Bantu is found written by Bleek is 1857. That year Bleek prepared a manuscript Zulu Legends (printed as late as 1952), in which he stated: <<The word 'aBa-ntu' (men, people) means 'Par excellence' individuals of the Kafir race, particularly in opposition to the noun 'aBe-lungu' (white men). -

AS CRIATURAS EM BAUDOLINO DE UMBERTO ECO: Criação De Um Bestiário Tridimensional

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universidade de Lisboa: Repositório.UL UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE BELAS-ARTES AS CRIATURAS EM BAUDOLINO DE UMBERTO ECO: criação de um bestiário tridimensional João Pedro Reis Rico dos Santos Trabalho de Projeto Mestrado em Desenho Trabalho de Projeto orientado pelo Prof. Doutor Henrique Antunes Prata Dias da Costa 2018 DECLARAÇÃO DE AUTORIA Eu João Pedro Reis Rico dos Santos, declaro que o trabalho de projeto de mestrado intitulada “As criaturas em Baudolino de Umberto Eco: criação de um bestiário tridimensional”, é o resultado da minha investigação pessoal e independente. O conteúdo é original e todas as fontes consultadas estão devidamente mencionadas na bibliografia ou outras listagens de fontes documentais, tal como todas as citações diretas ou indiretas têm devida indicação ao longo do trabalho segundo as normas académicas. O Candidato Lisboa, 31 Outubro 2018 2 RESUMO Propõe-se através deste trabalho a criação de um bestiário tridimensional a partir de “Baudolino” de Umberto Eco, onde se representarão em formato tridimensional através da modelação tridimensional cada uma das criaturas complementando a descrição de Eco com outras obtidas em diferentes bestiários recolhidos. Faz-se em primeiro lugar uma revisão do estado da arte, depois um breve estudo sobre o contexto histórico com particular enfase na queda de Constantinopla integrando- a na geografia fantástica das criaturas da terra de Prestes João. Desenvolve-se a investigação através da coleção de autores relacionados com o tema dos bestiários medievais, com destaque na criação digital de monstros e os seus autores, os casos de Plínio o Velho e das crónicas de Nuremberga. -

1 the Manchester Beatus

The Beatus Maps: Manchester #207.20 The Manchester (a.k.a. Rylands) Beatus mappa mundi, ca. 1175, John Rylands Library, MS. Lat. 8, fols. 43v-44r, Manchester, England, 45.4 x 32.6 cm The Manchester Beatus. The manuscript of Beatus’ Commentary of the Apocalypse of St. John now in Manchester, England was made around the year 1175 and it is ascribed to the Spanish Burgos region, specifically to the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña and to the region of Toledo. As a reference, this map falls into Peter Klein’s “Fourth Recension” and Wilhelm Neuss’ Family IIb stemma which consists of the following maps: • Manuscript of Tabara (970). Although its mappa mundi has not survived, as we said in reference to the manuscripts of the Commentary on the Apocalypse which contain the mappa mundi, it must have been very similar to the maps of Las Huelgas and Girona. • Mappa mundi of Girona. (975) #207.6. • Mappa mundi of Turin (first quarter of the 12th century) #207.15. • Mappa mundi of Manchester (ca. 1175) #207.20. • Mappa mundi of Las Huelgas (1220) #207.24. • Mappa mundi of San Andrés de Arroyo (ca. 200 - ca. 1248?) #207.25. 1 The Beatus Maps: Manchester #207.20 Sandra Sáenz-López Pérez has identified the following common features of this Family of Beatus mappae mundi: • The toponyms are virtually identical. Gonzalo Menendez-Pidal recognized the following as being inherent traits of these maps: the inclusion of Cappadocia and Mesopotamia, as well as the addition of the names of Gallia Belgica and Gallia Lugdunensis (instead of just the basic Gallias as shown in the maps of Family IIa).