Review Template.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Was There a Custom of Distributing the Booty in the Crusades of the Thirteenth Century?

Benjámin Borbás WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? MA Thesis in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies Central European University Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2019 WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, -

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Vol 33 (2011), No. 1

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Volume XXXIII, No. 1 May 2011 CONTENTS Articles Towards The Limits to Growth? The Book and its Reception in West Germany and Britain 1972–73 (Elke Seefried) 3 In Subsidium: The Declining Contribution of Germany and East- ern Europe to the Crusades to the Holy Land, 1221–91 (Nicholas Morton) 38 Review Article Normality, Utopia, Memory, and Beyond: Reassembling East German Society (Thomas Lindenberger) 67 Response to Thomas Lindenberger (Mary Fulbrook) 92 Book Reviews Jennifer R. Davis and Michael McCormick (eds.), The Long Morning of Medieval Europe: New Directions in Early Medi- eval Studies (Dominik Waßenhoven) 99 Das Lehnswesen im Hochmittelalter: Forschungskonstrukte— Quellen befunde—Deutungsrelevanz, ed. Jürgen Dendorfer and Roman Deut in ger (Thomas N. Bisson) 104 Jochen Burgtorf, The Central Convent of Hospitallers and Tem- plars: History, Organization, and Personnel (1099/1120–1310) (Karl Borchardt) 113 (cont.) Contents Oliver Auge, Handlungsspielräume fürstlicher Politik im Mittel- alter: Der südliche Ostseeraum von der Mitte des 12. Jahrhun- derts bis in die frühe Re formationszeit (Jonathan R. Lyon) 119 Dominik Haffer, Europa in den Augen Bismarcks: Bismarcks Vor stellungen von der Politik der europäischen Mächte und vom europäischen Staatensystem (Frank Lorenz Müller) 124 James Retallack (ed.), Imperial Germany 1871–1918 (Ewald Frie) 128 Dierk Hoffmann, Otto Grotewohl (1894–1964): Eine politische Bio gra phie (Norman LaPorte) 132 Jane Caplan and Nikolaus Wachsmann (eds.), Con cen -

The Teutonic Order and the Baltic Crusades

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 6-10-2019 The eutT onic Order and the Baltic Crusades Alex Eidler Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Eidler, Alex, "The eT utonic Order and the Baltic Crusades" (2019). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 273. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/273 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. The Teutonic Order and the Baltic Crusades By Alex Eidler Senior Seminar: Hst 499 Professor David Doellinger Western Oregon University June 5, 2019 Readers Professor Elizabeth Swedo Professor David Doellinger Copyright © Alex Eidler, 2019 Eidler 1 Introduction When people think of Crusades, they often think of the wars in the Holy Lands rather than regions inside of Europe, which many believe to have already been Christian. The Baltic Crusades began during the Second Crusade (1147-1149) but continued well into the fifteenth century. Unlike the crusades in the Holy Lands which were initiated to retake holy cities and pilgrimage sites, the Baltic crusades were implemented by the German archbishoprics of Bremen and Magdeburg to combat pagan tribes in the Baltic region which included Estonia, Prussia, Lithuania, and Latvia.1 The Teutonic Order, which arrived in the Baltic region in 1226, was successful in their smaller initial campaigns to combat raiders, as well as in their later crusades to conquer and convert pagan tribes. -

Military Orders (Helen Nicholson) Alan V. Murray, Ed. the Crusades

Military Orders (Helen Nicholson) activities such as prayer and attending church services. Members were admitted in a formal religious ceremony. They wore a religious habit, but did not follow a fully enclosed lifestyle. Lay members Alan V. Murray, ed. The Crusades. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2006, pp. 825–829. predominated over priests in the early years, while the orders were still active in military affairs. The military order was a form of religious order first established in the first quarter of the twelfth The military orders were part of a religious trend of the late eleventh and early twelfth century toward century with the function of defending Christians, as well as observing the three monastic vows of wider participation in the religious life and more emphasis on action as against contemplation. The poverty, chastity, and obedience. The first military order was the Order of the Temple, formally Cistercian Order, founded at the end of the eleventh century, allowed laity from nonnoble families to established in the kingdom of Jerusalem in January 1120, while the Order of the Hospital (or Order of enter their order to perform manual tasks; orders of canons, founded in the late eleventh and early St. John of Jerusalem) began in the eleventh century as a hospice for pilgrims in Jerusalem and later twelfth centuries, could play an active role in society as priests working in the community, unlike on developed military responsibilities, perhaps as early as the mid-1120s. The Templars and traditional monks who lived enclosed lives in their monasteries. In the same way, the military orders Hospitallers became supranational religious orders, whose operations on the frontiers of Christendom did not follow a fully enclosed lifestyle, followed an active vocation, and were composed largely of laity: were supported by donations of land, money, and privileges from across Latin Christendom. -

Read Transcript

History of the Crusades. Episode 223. The Baltic Crusades. The Prussian Crusade Part V. The Teutonic Knights. Hello again. Last week we saw Duke Konrad of Mazovia ask the Teutonic Order to send an army to Prussia to Christianize the local Prussians, in exchange for land in the region of Kulm. This move, which effectively outsourced the conquering of Prussia to forces outside Poland, was born of desperation. Years of attempted Christianization of Prussia by preaching and by crusading, had failed to yield any permanent results. So, really, if Bishop Christian wanted his Bishopric of Prussia to be full of Christian converts, all faithfully paying tithes to the church, this was the only means left available to achieve it. So we left last week's episode with members of the Teutonic Order journeying back to the Holy Roman Empire from Mazovia, bearing with them a formal offer from Duke Konrad, witnessed by Bishop Christian. The offer was made to the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order Hermann von Salza, and stated that the order would be provided with land inside Prussia if they provided military assistance, which was to be used to Christianize Prussia. Now, before the members of the Teutonic Order arrive back in the Holy Roman Empire and hand the offer over to their Grand Master, we should take a look at how the Teutonic Order itself has been faring in recent times. We last examined the Order way back in Episode 193. In that episode, we saw how the Order was established in the Holy Land in the year 1198, originally to care for sick and injured German crusaders, and later to build and garrison castles in strategic locations in the Holy Land. -

RUDOLF HIESTAND Kingship and Crusade in Twelfth-Century Germany

RUDOLF HIESTAND Kingship and Crusade in Twelfth-Century Germany in ALFRED HAVERKAMP AND HANNA VOLLRATH (eds.), England and Germany in the High Middle Ages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996) pp. 235–265 ISBN: 978 0 19 920504 3 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 10 Kingship and Crusade in Twelfth-Century Germany RUDOLF HIESTAND The title of ·this essay may seem paradoxical. Otto of Freising's chronicle contains a well-known passage deploring that because of the schism, Urban II's proclamation at Clermont 'Francos orientales minus permovit' .1 As for the Second Crusade, in which he had participated, he declares quite frankly that he will not discuss it at any length. 2 Most modern historians of the crusades accept his account. They describe the First Crusade as an enterprise in which no Germans except for Geoffrey of Bouillon and his men from Lorraine -

The Clash Between Pagans and Christians: the Baltic Crusades from 1147-1309

The Clash between Pagans and Christians: The Baltic Crusades from 1147-1309 Honors Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in History in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Donald R. Shumaker The Ohio State University May 2014 Project Advisor: Professor Heather J. Tanner, Department of History 1 The Baltic Crusades started during the Second Crusade (1147-1149), but continued into the fifteenth century. Unlike the crusades in the Holy Lands, the Baltic Crusades were implemented in order to combat the pagan tribes in the Baltic. These crusades were generally conducted by German and Danish nobles (with occasional assistance from Sweden) instead of contingents from England and France. Although the Baltic Crusades occurred in many different countries and over several centuries, they occurred as a result of common root causes. For the purpose of this study, I will be focusing on the northern crusades between 1147 and 1309. In 1309 the Teutonic Order, the monastic order that led these crusades, moved their headquarters from Venice, where the Order focused on reclaiming the Holy Lands, to Marienberg, which was on the frontier of the Baltic Crusades. This signified a change in the importance of the Baltic Crusades and the motivations of the crusaders. The Baltic Crusades became the main theater of the Teutonic Order and local crusaders, and many of the causes for going on a crusade changed at this time due to this new focus. Prior to the year 1310 the Baltic Crusades occurred for several reasons. A changing knightly ethos combined with heightened religious zeal and the evolution of institutional and ideological changes in just warfare and forced conversions were crucial in the development of the Baltic Crusades. -

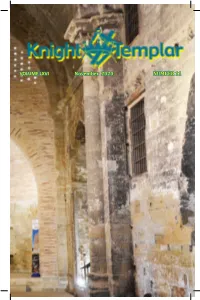

VOLUME LXVI November 2020 NUMBER 11

VOLUME LXVI November 2020 NUMBER 11 VOLUME LXVI NOVEMBER 2020 NUMBER 11 Published monthly as an official publication of the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar of the United States of America. Jeffrey N. Nelson Grand Master Jeffrey A. Bolstad Contents Grand Captain General and Publisher 325 Trestle Lane Grand Master’s Message Lewistown, MT 59457 Grand Master Jeffrey N. Nelson ..................... 4 Address changes or corrections La Forbie — The Beginning of the End and all membership activity for Frankish Outremer including deaths should be Sir Knight George L. Marshall, Jr., PGC ............. 7 reported to the recorder of the What’s the Point of a Sword? local Commandery. Please do Sir Knight John D. Barnes, PGC ...................... 12 not report them to the editor. Modern Day Chivalry Lawrence E. Tucker Sir Knight Thomas Hendrickson, PGM ........... 21 Grand Recorder Time To Move On Grand Encampment Office 5909 West Loop South, Suite 495 Reverend and Sir Knight J.B. Morris .............. 27 Bellaire, TX 77401-2402 Knights Templar Holy Land Pilgrimage Phone: (713) 349-8700 Fax: (713) 349-8710 for Sir Knights, their Ladies, and Friends ....... 30 E-mail: [email protected] Magazine materials and correspon- dence to the editor should be sent in elec- tronic form to the managing editor whose Features contact information is shown below. Materials and correspondence concern- Prelate’s Chapel ..................................................... 6 ing the Grand Commandery state supple- ments should be sent to the respective supplement editor. Focus on Chivalry .................................................. 14 John L. Palmer Leadership Notes - Delegating Effectively .............. 15 Managing Editor Post Office Box 566 The Knights Templar Eye Foundation ........5,16,17,20 Nolensville, TN 37135-0566 Phone: (615) 283-8477 Grand Commandery Supplement ......................... -

The Seventh Crusade ST

ST. MARY THE VIRGIN Sovereign Military Order of the Temple of Jerusalem The Seventh Crusade ST. MARY THE VIRGIN The Seventh Crusade First Edition 2021 Prepared by Dr. Chev. Peter L. Heineman, GOTJ, CMTJ 2020 Avenue B Council Bluffs, IA 51501 Phone 712.323.3531• www.plheineman.net Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Historical Context ....................................................................................... 2 The Campaign ........................................................................................... 3 Cyprus ............................................................................................. 4 Damietta .......................................................................................... 4 Cairo ............................................................................................... 5 Battle of Monsourah ........................................................................ 5 Battle of Fariskur ............................................................................. 6 Aftermath ................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION Seventh Crusade he Seventh Crusade (1248-1254) was led by the French king Louis IX (r. 1226-1270) who intended to conquer Egypt and take over Jerusalem; both then controlled by the Muslim Ayyubid Dynasty. Despite the initial success of capturing Damietta on the Nile, Louis' troops were defeated by the T -

Extracts from the Chronicles of Matthew Paris Relating to the Templars, Hospitallers and Teutonic Knights Translated from the Rolls Series Editions by Helen J

Cardiff University, School of History, Archaeology and Religion HS 1805 The Military Orders, 1100–1320; HST 908 The Military Orders Documents relating to the Military Orders Translated by Helen J. Nicholson. Original translations 1988–98; this edition 2013 Extracts from the chronicles of Matthew Paris relating to the Templars, Hospitallers and Teutonic Knights translated from the Rolls Series editions by Helen J. Nicholson Contents Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora [The Greater Chronicle] ...................................................................... 2 Vol. 3 .................................................................................................................................................... 2 About the Templars’ and Hospitallers’ pride and jealousy .............................................................. 2 The letter of Gerald, patriarch of Jerusalem ..................................................................................... 3 Thierry, the prior of the Hospital in England, is sent to help the Holy Land. ................................... 6 Vol. 4 .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Delightful events in the Holy Land about a peace treaty which had been made. But it had a very sad outcome. ..................................................................................................................................... 9 The Battle of La Forbie ................................................................................................................... -

The Dear Old Holy Roman Realm. How Does It Hold Together? Goethe, Faust I, Scene 5

Economic History Working Papers No: 288 “The Dear Old Holy Roman Realm. How Does it Hold Together?” Monetary Policies, Cross-cutting Cleavages and Political Cohesion in the Age of Reformation Oliver Volckart LSE October 2018 July 2018 Economic History Department, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, London, UK. T: +44 (0) 20 7955 7084. F: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 ‘The Dear Old Holy Roman Realm, How Does it Hold Together?’ Monetary Policies, Cross-cutting Cleavages and Political Cohesion in the Age of Reformation Oliver Volckart JEL codes: H11, H77, N13, N43. Keywords: Holy Roman Empire, Reformation, political cohesion, monetary policies. Abstract Research has rejected Ranke’s hypothesis that the Reformation emasculated the Holy Roman Empire and thwarted the emergence of a German nation state for centuries. However, current explanations of the Empire’s cohesion that emphasise the effects of outside pressure or political rituals are not entirely satisfactory. This article contributes to a fuller explanation by examining a factor that so far has been overlooked: monetary policies. Monetary conditions within the Empire encouraged its members to cooperate with each other and the emperor. Moreover, cross-cutting cleavages – i.e. the fact that both Catholics and Protestants were split among themselves in monetary-policy questions – allowed actors on different sides of the confessional divide to find common ground. The paper analyses the extent to which cleavages affected the negotiations about the creation of a common currency between the 1520s and the 1550s, and whether monetary policies helped bridging the religious divide, thus increasing the Empire’s political cohesion. -

The German Crusade of 1197–1198

This is a repository copy of The German Crusade of 1197–1198. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/82933/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Loud, GA (2014) The German Crusade of 1197–1198. Crusades, 13 (1). pp. 143-172. ISSN 1476-5276 © 2015, by the Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Ashgate Publishing in Crusades on 01 Jun 2014, available online: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/ashgate/cru/2014/00000013/00000001/art000 07. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 The German Crusade of 1197-98 G.A. Loud University of Leeds [email protected] Abstract This article reconsiders the significance of the German Crusade of 1197-8, often dismissed as a very minor episode in the history of the Crusading movement.