History of the Crusades. Episode 100 Baibars. Wait, Did I Just Say Episode

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Was There a Custom of Distributing the Booty in the Crusades of the Thirteenth Century?

Benjámin Borbás WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? MA Thesis in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies Central European University Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2019 WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, -

The Sultan, the Tyrant, and the Hero: Changing Medieval Perceptions of Al-Zahir Baybars (MSR IV, 2000)

AMINA A. ELBENDARY AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO The Sultan, The Tyrant, and The Hero: Changing Medieval Perceptions of al-Z˛a≠hir Baybars* As the true founder of the Mamluk state, al-Z˛a≠hir Baybars is one of the most important sultans of Egypt and Syria. This has prompted many medieval writers and historians to write about his reign. Their perceptions obviously differed and their reconstructions of his reign draw different and often conflicting images. In this article I propose to examine and compare the various perceptions that different writers had of Baybars's life and character. Each of these writers had his own personal biases and his own purposes for writing about Baybars. The backgrounds against which they each lived and worked deeply influenced their writings. This led them to emphasize different aspects of his personality and legacy and to ignore others. Comparing these perceptions will demonstrate how the historiography of Baybars was used to make different political arguments concerning the sultan, the Mamluk regime, and rulership in general. I have used different representative examples of thirteenth- to fifteenth-century histories, chronicles, and biographical dictionaries in compiling this material. I have also compared these scholarly writings to the popular folk epic S|rat al-Z˛a≠hir Baybars. In his main official biography, written by Muh˛y| al-D|n ibn ‘Abd al-Z˛a≠hir, Baybars is presented as an ideal sultan. By contrast, works written after the sultan's day show more ambivalent attitudes towards him. Some fourteenth-century writers, like Sha≠fi‘ ibn ‘Al|, Baybars al-Mans˝u≠r|, and al-Nuwayr|, who were influenced by the regime of al-Na≠s˝ir Muh˛ammad, tend to place more emphasis on his despotic actions. -

Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi POWER, POLITICS, AND TRADITION IN THE MONGOL EMPIRE AND THE ĪlkhānaTE OF IRAN OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Īlkhānate of Iran MICHAEL HOPE 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6D P, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Michael Hope 2016 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2016932271 ISBN 978–0–19–876859–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson

The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 1 Copyright Statement This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed to the owner of the Intellectual Property Rights. 2 Abstract The Latin principality of Antioch was founded during the First Crusade (1095-1099), and survived for 170 years until its destruction by the Mamluks in 1268. This thesis offers the first full assessment of the thirteenth century principality of Antioch since the publication of Claude Cahen’s La Syrie du nord à l’époque des croisades et la principauté franque d’Antioche in 1940. It examines the Latin principality from its devastation by Saladin in 1188 until the fall of Antioch eighty years later, with a particular focus on its relationship with the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia. This thesis shows how the fate of the two states was closely intertwined for much of this period. The failure of the principality to recover from the major territorial losses it suffered in 1188 can be partly explained by the threat posed by the Cilician Armenians in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. -

A Guide to Al-Aqsa Mosque Al-Haram Ash-Sharif Contents

A Guide to Al-Aqsa Mosque Al-Haram Ash-Sharif Contents In the name of Allah, most compassionate, most merciful Introduction JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<3 Dear Visitor, Mosques JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<<4 Welcome to one of the major Islamic sacred sites and landmarks Domes JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<24 of civilization in Jerusalem, which is considered a holy city in Islam because it is the city of the prophets. They preached of the Minarets JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<30 Messenger of God, Prophet Mohammad (PBUH): Arched Gates JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<32 The Messenger has believed in what was revealed to him from his Lord, and [so have] the believers. All of them have believed in Allah and His angels and Schools JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<36 His books and His messengers, [saying], “We make no distinction between any of His messengers.” And they say, “We hear and we obey. [We seek] Your Corridors JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<44 forgiveness, our Lord, and to You is the [final] destination” (Qur’an 2:285). Gates JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<46 It is also the place where one of Prophet Mohammad’s miracles, the Night Journey (Al-Isra’ wa Al-Mi’raj), took place: Water Sources JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<54 Exalted is He who took His Servant -

Download Date 04/10/2021 06:40:30

Mamluk cavalry practices: Evolution and influence Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nettles, Isolde Betty Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 06:40:30 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289748 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this roproduction is dependent upon the quaiity of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that tfie author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal secttons with small overlaps. Photograpiis included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrattons appearing in this copy for an additk)nal charge. -

The Ilkhanid Mongols, the Christian Armenians, and the Islamic Mamluks : a Study of Their Relations, 1220-1335

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2012 The Ilkhanid Mongols, the Christian Armenians, and the Islamic Mamluks : a study of their relations, 1220-1335. Lauren Prezbindowski University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Prezbindowski, Lauren, "The Ilkhanid Mongols, the Christian Armenians, and the Islamic Mamluks : a study of their relations, 1220-1335." (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1152. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1152 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ILKHANID MONGOLS, THE CHRISTIAN ARMENIANS, AND THE ISLAMIC MAMLUKS: A STUDY OF THEIR RELATIONS, 1220-1335 By Lauren Prezbindowski B.A., Hanover College, 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville December 2012 THE ILKHANID MONGOLS, THE CHRISTIAN ARMENIANS, AND THE ISLAMIC MAMLUKS: A STUDY OF THEIR RELATIONS, 1220-1335 By Lauren Prezbindowski B.A., Hanover College, 2008 A Thesis Approved on November 15,2012 By the following Thesis Committee: Dr. John McLeod, Thesis Director Dr. -

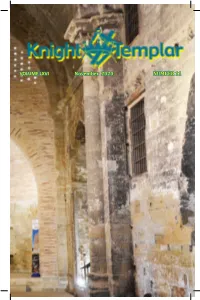

VOLUME LXVI November 2020 NUMBER 11

VOLUME LXVI November 2020 NUMBER 11 VOLUME LXVI NOVEMBER 2020 NUMBER 11 Published monthly as an official publication of the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar of the United States of America. Jeffrey N. Nelson Grand Master Jeffrey A. Bolstad Contents Grand Captain General and Publisher 325 Trestle Lane Grand Master’s Message Lewistown, MT 59457 Grand Master Jeffrey N. Nelson ..................... 4 Address changes or corrections La Forbie — The Beginning of the End and all membership activity for Frankish Outremer including deaths should be Sir Knight George L. Marshall, Jr., PGC ............. 7 reported to the recorder of the What’s the Point of a Sword? local Commandery. Please do Sir Knight John D. Barnes, PGC ...................... 12 not report them to the editor. Modern Day Chivalry Lawrence E. Tucker Sir Knight Thomas Hendrickson, PGM ........... 21 Grand Recorder Time To Move On Grand Encampment Office 5909 West Loop South, Suite 495 Reverend and Sir Knight J.B. Morris .............. 27 Bellaire, TX 77401-2402 Knights Templar Holy Land Pilgrimage Phone: (713) 349-8700 Fax: (713) 349-8710 for Sir Knights, their Ladies, and Friends ....... 30 E-mail: [email protected] Magazine materials and correspon- dence to the editor should be sent in elec- tronic form to the managing editor whose Features contact information is shown below. Materials and correspondence concern- Prelate’s Chapel ..................................................... 6 ing the Grand Commandery state supple- ments should be sent to the respective supplement editor. Focus on Chivalry .................................................. 14 John L. Palmer Leadership Notes - Delegating Effectively .............. 15 Managing Editor Post Office Box 566 The Knights Templar Eye Foundation ........5,16,17,20 Nolensville, TN 37135-0566 Phone: (615) 283-8477 Grand Commandery Supplement ......................... -

The Seventh Crusade ST

ST. MARY THE VIRGIN Sovereign Military Order of the Temple of Jerusalem The Seventh Crusade ST. MARY THE VIRGIN The Seventh Crusade First Edition 2021 Prepared by Dr. Chev. Peter L. Heineman, GOTJ, CMTJ 2020 Avenue B Council Bluffs, IA 51501 Phone 712.323.3531• www.plheineman.net Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Historical Context ....................................................................................... 2 The Campaign ........................................................................................... 3 Cyprus ............................................................................................. 4 Damietta .......................................................................................... 4 Cairo ............................................................................................... 5 Battle of Monsourah ........................................................................ 5 Battle of Fariskur ............................................................................. 6 Aftermath ................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION Seventh Crusade he Seventh Crusade (1248-1254) was led by the French king Louis IX (r. 1226-1270) who intended to conquer Egypt and take over Jerusalem; both then controlled by the Muslim Ayyubid Dynasty. Despite the initial success of capturing Damietta on the Nile, Louis' troops were defeated by the T -

![Cilician Armenia in the Thirteenth Century.[3] Marco Polo, for Example, Set out on His Journey to China from Ayas in 1271](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9192/cilician-armenia-in-the-thirteenth-century-3-marco-polo-for-example-set-out-on-his-journey-to-china-from-ayas-in-1271-1709192.webp)

Cilician Armenia in the Thirteenth Century.[3] Marco Polo, for Example, Set out on His Journey to China from Ayas in 1271

The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (also known as Little Armenia; not to be confused with the Arme- nian Kingdom of Antiquity) was a state formed in the Middle Ages by Armenian refugees fleeing the Seljuk invasion of Armenia. It was located on the Gulf of Alexandretta of the Mediterranean Sea in what is today southern Turkey. The kingdom remained independent from around 1078 to 1375. The Kingdom of Cilicia was founded by the Rubenian dynasty, an offshoot of the larger Bagratid family that at various times held the thrones of Armenia and Georgia. Their capital was Sis. Cilicia was a strong ally of the European Crusaders, and saw itself as a bastion of Christendom in the East. It also served as a focus for Armenian nationalism and culture, since Armenia was under foreign oc- cupation at the time. King Levon I of Armenia helped cultivate Cilicia's economy and commerce as its interaction with European traders grew. Major cities and castles of the kingdom included the port of Korikos, Lam- pron, Partzerpert, Vahka (modern Feke), Hromkla, Tarsus, Anazarbe, Til Hamdoun, Mamistra (modern Misis: the classical Mopsuestia), Adana and the port of Ayas (Aias) which served as a Western terminal to the East. The Pisans, Genoese and Venetians established colonies in Ayas through treaties with Cilician Armenia in the thirteenth century.[3] Marco Polo, for example, set out on his journey to China from Ayas in 1271. For a short time in the 1st century BCE the powerful kingdom of Armenia was able to conquer a vast region in the Levant, including the area of Cilicia. -

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & the Exuberance of Mamluk Design

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & The Exuberance of Mamluk Design Tarek A. El-Akkad Dipòsit Legal: B. 17657-2013 ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del s eu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. -

Cilician Armenian Mediation in Crusader-Mongol Politics, C.1250-1350

HAYTON OF KORYKOS AND LA FLOR DES ESTOIRES: CILICIAN ARMENIAN MEDIATION IN CRUSADER-MONGOL POLITICS, C.1250-1350 by Roubina Shnorhokian A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (January, 2015) Copyright ©Roubina Shnorhokian, 2015 Abstract Hayton’s La Flor des estoires de la terre d’Orient (1307) is typically viewed by scholars as a propagandistic piece of literature, which focuses on promoting the Ilkhanid Mongols as suitable allies for a western crusade. Written at the court of Pope Clement V in Poitiers in 1307, Hayton, a Cilician Armenian prince and diplomat, was well-versed in the diplomatic exchanges between the papacy and the Ilkhanate. This dissertation will explore his complex interests in Avignon, where he served as a political and cultural intermediary, using historical narrative, geography and military expertise to persuade and inform his Latin audience of the advantages of allying with the Mongols and sending aid to Cilician Armenia. This study will pay close attention to the ways in which his worldview as a Cilician Armenian informed his perceptions. By looking at a variety of sources from Armenian, Latin, Eastern Christian, and Arab traditions, this study will show that his knowledge was drawn extensively from his inter-cultural exchanges within the Mongol Empire and Cilician Armenia’s position as a medieval crossroads. The study of his career reflects the range of contacts of the Eurasian world. ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the financial support of SSHRC, the Marjorie McLean Oliver Graduate Scholarship, OGS, and Queen’s University.