The Ilkhanid Mongols, the Christian Armenians, and the Islamic Mamluks : a Study of Their Relations, 1220-1335

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quarterly Update on Conflict and Diplomacy Source: Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol

Quarterly Update on Conflict and Diplomacy Source: Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 32, No. 4 (Summer 2003), pp. 128-149 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Institute for Palestine Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jps.2003.32.4.128 . Accessed: 25/03/2015 15:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and Institute for Palestine Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Palestine Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 66.134.128.11 on Wed, 25 Mar 2015 15:58:14 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions QUARTERLY UPDATE ON CONFLICT AND DIPLOMACY 16 FEBRUARY–15 MAY 2003 COMPILED BY MICHELE K. ESPOSITO The Quarte rlyUp date is asummaryofbilate ral, multilate ral, regional,andinte rnationa l events affecting th ePalestinians andth efutureofth epeaceprocess. BILATERALS 29foreign nationals had beenkilled since 9/28/00. PALESTINE-ISRAEL Positioningf orWaronIraq Atthe opening of thequarter, Ariel Tokeep up the appearance of Sharon had beenreelected PM of Israel movementon thepeace process in the and was in theprocess of forming a run-up toawar on Iraq, theQuartet government.U.S. -

Muhammad Uljaytu's Conversion to Islam Key Terms

Muhammad Uljaytu’s Conversion to Islam Seyyedeh Samira Behzadi1 After the Mongols’ invasion of Iran, no one could ever imagine that the grand children of Genghis Khan would pave the context for the growth and dissemination of Islam in later periods. Genghis Khan, himself, was a shaman and his grandsons, such as Hulagu Khan and Abaqa Khan, and Abaqa Khan’s children were Buddhists. However, they always dealt with the followers of other religions and sects with respect. The court of Hulagu Khan in Iran was always frequented by the scholars of other religions. Some of the children and grandchildren of Hulagu Khan abandoned their ancestral religion because of the necessities of their time and converted to Islam or Christianity. In this regard, reference can be made to Ghazan Khan and Muhammad Uljaytu who, because of the penetration of Muslim scholars in their courts, paid attention to Islam and Shi’ism. Ghazan Khan chose the Hanafite religion but did not formally acknowledge his conversion to Shi’ism for certain political reasons. Muhammad Uljaytu, his brother, persuaded the king to follow Shi’ism more openly for several reasons including the penetration of some Muslim scholars and Shi’iteministers and rulers, such as Allamah al-Hilli, his son Fakhr ul- Muhaqqiqin, and Amir TarmTaz, in his court and their arguments as to the superiority of Shi’ism over Sunnism. Uljaytu chose the Twelver branch of Shi’ism and, at the sometime, issued the order of reading sermons in Friday prayers in the name of the Shi’ite Imams (a) and minting coins in their names. -

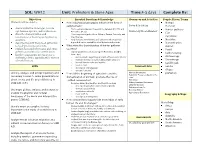

SOL: WHI.2 Unit: Prehistory & Stone Ages Time:4-5 Days Complete

SOL: WHI.2 Unit: Prehistory & Stone Ages Time:4-5 days Complete By: Objectives Essential Questions & Knowledge Resources and Activities People, Places, Terms Students will be able to: How did physical geography influence the lives of Nomad early humans? Notes & Activities Hominid characterize the stone ages, bronze Homo sapiens emerged in east Africa between 100,000 and Hunter-gatherer age, human species, and civilizations. 400,000 years ago. Prehistory Vocab Handout Clan describe characteristics and Homo sapiens migrated from Africa to Eurasia, Australia, and innovations of hunting and gathering the Americas. Paleolithic societies. Early humans were hunters and gatherers whose survival Neolithic describe the shift from food gathering depended on the availability of wild plants and animals. Domestication to food-producing activities. What were the characteristics of hunter gatherer Artifact explain how and why towns and cities societies? Fossil grew from early human settlements. Hunter-gatherer societies during the Paleolithic Era (Old Carbon dating list the components necessary for a Stone Age) Archaeology civilization while applying their themes o were nomadic, migrating in search of food, water, shelter of world history. o invented the first tools, including simple weapons Stonehenge o learned how to make and use fire Catal hoyuk Skills o lived in clans Internet Links Jericho o developed oral language o created “cave art.” Aleppo Human Organisms Identify, analyze, and interpret primary and How did the beginning of agriculture and the prehistory Paleolithic Era versus Neolithic Era secondary sources to make generalizations domestication of animals promote the rise of chart about events and life in world history to settled communities? Prehistory 1500 A.D. -

DOI: 10.22378/2313-6197.2017-5-3 ISSN 2313-6197 (Online) ISSN 2308-152X (Print) ЗОЛОТООРДЫНСКОЕ ОБОЗРЕНИЕ 2017

DOI: 10.22378/2313-6197.2017-5-3 ISSN 2313-6197 (Online) ISSN 2308-152X (Print) ЗОЛОТООРДЫНСКОЕ ОБОЗРЕНИЕ 2017. Том 5, № 3 ZOLOTOORDYNSKOE OBOZRENIE= G OLDEN H ORDE R EVIEW 2017. Vol. 5, no. 3 Научный журнал Academic Journal УЧРЕДИТЕЛЬ: FOUNDER: ГБУ «Институт истории State Institution им. Ш. Марджани Академии наук «Sh.Marjani Institute of History Республики Татарстан» of Tatarstan Academy of Sciences» Свидетельство о регистрации СМИ Certificate of registration in the mass media ПИ № ФС77–54682 от 9 июля 2013 г. ПИ № ФС77–54682 given by Roskomnadzor выдано Роскомнадзором on 9 July 2013 Журнал основан в апреле 2013 г. Journal was founded in April 2013 Выходит 4 раза в год Published 4 times a year РЕДАКЦИЯ: EDITORIAL OFFICE: 420014, г. Казань, Кремль, подъезд 5 (юрид.) 420014, Kazan, Kremlin, entrance 5 (juridical) 420111, г. Казань, ул. Батурина, 7 420111, Kazan, Baturin Str., 7 Тел./факс (843) 292 84 82 (приемная), Tel./Fax (843) 292 84 82 (reception), 292 00 19 292 00 19 Подписной индекс в каталоге Subscription index in the «Catalogue «Каталог Российской Прессы» – 31999 of the Russian Press» – 31999 ЖУРНАЛ ИНДЕКСИРУЕТСЯ В: THE JOURNAL IS INDEXED BY: Scopus Scopus Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory Российский индекс научного Russian Science Citation цитирования (РИНЦ), РГБ Index Database, RSL AcademicKeys, WorldCat AcademicKeys, WorldCat Научная электронная библиотека Scientific Electronic Open Access открытого доступа КиберЛенинка Library CyberLeninka Google Scholar, СОЦИОНЕТ Google Scholar, SOCIONET Журнал входит в Перечень российских рецензируемых научных журналов, в которых должны быть опубликованы основные научные результаты диссертаций на соискание ученых степеней доктора и кандидата наук (список научных журналов ВАК МОиН РФ) http://goldhorde.ru E-mail: [email protected] © ГБУ «Институт истории им. -

Saleh Poll Tax December 2011

On the Road to Heaven: Poll tax, Religion, and Human Capital in Medieval and Modern Egypt Mohamed Saleh* University of Southern California (Preliminary and Incomplete: December 1, 2011) Abstract In the Middle East, non-Muslims are, on average, better off than the Muslim majority. I trace the origins of the phenomenon in Egypt to the imposition of the poll tax on non- Muslims upon the Islamic Conquest of the then-Coptic Christian Egypt in 640. The tax, which remained until 1855, led to the conversion of poor Copts to Islam to avoid paying the tax, and to the shrinking of Copts to a better off minority. Using new data sources that I digitized, including the 1848 and 1868 census manuscripts, I provide empirical evidence to support the hypothesis. I find that the spatial variation in poll tax enforcement and tax elasticity of conversion, measured by four historical factors, predicts the variation in the Coptic population share in the 19th century, which is, in turn, inversely related to the magnitude of the Coptic-Muslim gap, as predicted by the hypothesis. The four factors are: (i) the 8th and 9th centuries tax revolts, (ii) the Arab immigration waves to Egypt in the 7th to 9th centuries, (iii) the Coptic churches and monasteries in the 12th and 15th centuries, and (iv) the route of the Holy Family in Egypt. I draw on a wide range of qualitative evidence to support these findings. Keywords: Islamic poll tax; Copts, Islamic Conquest; Conversion; Middle East JEL Classification: N35 * The author is a PhD candidate at the Department of Economics, University of Southern California (E- mail: [email protected]). -

Mongol Lawâ•Fla Concise Historical Survey

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by UW Law Digital Commons (University of Washington) Washington Law Review Volume 23 Number 2 5-1-1948 Mongol Law—A Concise Historical Survey V. A. Riasanovsky Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr Digital Par t of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Commons Network Recommended Citation Logo V. A. Riasanovsky, Far Eastern Section, Mongol Law—A Concise Historical Survey, 23 Wash. L. Rev. & St. B.J. 166 (1948). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol23/iss2/9 This Far Eastern Section is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington Law Review by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON LAW REVIEW Soviet society is thought of as a moral or "moral-political" unity; its members are but youths and children, requiring training and educa- tion, Soviet law educates them to a Communist social-consciousness, "ingrafting upon them," in the words of a recent Soviet writer," "high, noble feelings." However repressive the Soviet legal system may ap- pear to the "reasonable man" of American tradition, the importance of the underlying conception of Law as a teacher should not be minimized. 14 Kareva, The Role of Soviet Law in the Education of Communist Conscsousness, BOLSHEVIK, No. 4 (in Russian) (1947). MONGOL LAW-A CONCISE HISTORICAL SURVEY V A. RiAsANOVSKY* Two basic systems of law, one Chinese, the other Mongol, co- existed in Eastern Asia. -

Protagonist of Qubilai Khan's Unsuccessful

BUQA CHĪNGSĀNG: PROTAGONIST OF QUBILAI KHAN’S UNSUCCESSFUL COUP ATTEMPT AGAINST THE HÜLEGÜID DYNASTY MUSTAFA UYAR* It is generally accepted that the dissolution of the Mongol Empire began in 1259, following the death of Möngke the Great Khan (1251–59)1. Fierce conflicts were to arise between the khan candidates for the empty throne of the Great Khanate. Qubilai (1260–94), the brother of Möngke in China, was declared Great Khan on 5 May 1260 in the emergency qurultai assembled in K’ai-p’ing, which is quite far from Qara-Qorum, the principal capital of Mongolia2. This event started the conflicts within the Mongolian Khanate. The first person to object to the election of the Great Khan was his younger brother Ariq Böke (1259–64), another son of Qubilai’s mother Sorqoqtani Beki. Being Möngke’s brother, just as Qubilai was, he saw himself as the real owner of the Great Khanate, since he was the ruler of Qara-Qorum, the main capital of the Mongol Khanate. Shortly after Qubilai was declared Khan, Ariq Böke was also declared Great Khan in June of the same year3. Now something unprecedented happened: there were two competing Great Khans present in the Mongol Empire, and both received support from different parts of the family of the empire. The four Mongol khanates, which should theo- retically have owed obedience to the Great Khan, began to act completely in their own interests: the Khan of the Golden Horde, Barka (1257–66) supported Böke. * Assoc. Prof., Ankara University, Faculty of Languages, History and Geography, Department of History, Ankara/TURKEY, [email protected] 1 For further information on the dissolution of the Mongol Empire, see D. -

The Grain Economy of Mamluk Egypt by Ira M. Lapidus

THE GRAIN ECONOMY OF MAMLUK EGYPT BY IRA M. LAPIDUS (University of California, Berkeley) Scholarly studies of the economy of Egypt in the Middle Ages, from the Fatimid through the Mamluk periods, have stressed two seemingly contradictory themes. On the one hand, the extraordinary involvement of the state in economic affairs is manifest. At different times, and in various ways, the ruling regimes of Egypt monopolized or strictly controlled certain primary or strategic products. Wood and metals, both domestic and imported, were strictly controlled to assure the availability of military supplies. Certain export products like natron were sometimes made state monopolies. So too products of unusual commercial importance were exploited, especially by the Mamluk Sultans, to gain monetary advantages. Sugar production, often in the hands of rulers and oflicials, was also, on occasion, a state monopoly. At another level, the state participated in economic activity it did not monopolize. Either the governing bureaus themselves, or elite members of the regime, were responsible for irrigation and other investments essential to agricultural productivity. In the trading sphere, though state-sponsored trading expeditions are unknown, state support for trade by treaty arrangements, by military and diplomatic protection, and direct participation in the form of investments placed with mer- chants were characteristic activities. How much of the capital of trade was "booty" or political capital we shall never know. In other spheres, state participation gave way to state controls for the purposes of taxation. Regulation of the movements of merchants, or the distribution of goods, facilitated taxation. For religious or moral reasons state controls also extended to the supervision, regulation, or prohibition of certain illicit trades. -

Nomadic Incursion MMW 13, Lecture 3

MMW 13, Lecture 3 Nomadic Incursion HOW and Why? The largest Empire before the British Empire What we talked about in last lecture 1) No pure originals 2) History is interrelated 3) Before Westernization (16th century) was southernization 4) Global integration happened because of human interaction: commerce, religion and war. Known by many names “Ruthless” “Bloodthirsty” “madman” “brilliant politician” “destroyer of civilizations” “The great conqueror” “Genghis Khan” Ruling through the saddle Helped the Eurasian Integration Euroasia in Fragments Afro-Eurasia Afro-Eurasian complex as interrelational societies Cultures circulated and accumulated in complex ways, but always interconnected. Contact Zones 1. Eurasia: (Hemispheric integration) a) Mediterranean-Mesopotamia b) Subcontinent 2) Euro-Africa a) Africa-Mesopotamia 3) By the late 15th century Transatlantic (Globalization) Africa-Americas 12th century Song and Jin dynasties Abbasids: fragmented: Fatimads in Egypt are overtaken by the Ayyubid dynasty (Saladin) Africa: North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa Europe: in the periphery; Roman catholic is highly bureaucratic and society feudal How did these zones become connected? Nomadic incursions Xiongunu Huns (Romans) White Huns (Gupta state in India) Avars Slavs Bulgars Alans Uighur Turks ------------------------------------------------------- In Antiquity, nomads were known for: 1. War 2. Migration Who are the Nomads? Tribal clan-based people--at times formed into confederate forces-- organized based on pastoral or agricultural economies. 1) Migrate so to adapt to the ecological and changing climate conditions. 2) Highly competitive on a tribal basis. 3) Religion: Shamanistic & spirit-possession Two Types of Nomadic peoples 1. Pastoral: lifestyle revolves around living off the meat, milk and hides of animals that are domesticated as they travel through arid lands. -

Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi POWER, POLITICS, AND TRADITION IN THE MONGOL EMPIRE AND THE ĪlkhānaTE OF IRAN OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Īlkhānate of Iran MICHAEL HOPE 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6D P, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Michael Hope 2016 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2016932271 ISBN 978–0–19–876859–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Phd 15.04.27 Versie 3

Promotor Prof. dr. Jan Dumolyn Vakgroep Geschiedenis Decaan Prof. dr. Marc Boone Rector Prof. dr. Anne De Paepe Nederlandse vertaling: Een Spiegel voor de Sultan. Staatsideologie in de Vroeg Osmaanse Kronieken, 1300-1453 Kaftinformatie: Miniature of Sultan Orhan Gazi in conversation with the scholar Molla Alâeddin. In: the Şakayıku’n-Nu’mâniyye, by Taşköprülüzâde. Source: Topkapı Palace Museum, H1263, folio 12b. Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Hilmi Kaçar A Mirror for the Sultan State Ideology in the Early Ottoman Chronicles, 1300- 1453 Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Geschiedenis 2015 Acknowledgements This PhD thesis is a dream come true for me. Ottoman history is not only the field of my research. It became a passion. I am indebted to Prof. Dr. Jan Dumolyn, my supervisor, who has given me the opportunity to take on this extremely interesting journey. And not only that. He has also given me moral support and methodological guidance throughout the whole process. The frequent meetings to discuss the thesis were at times somewhat like a wrestling match, but they have always been inspiring and stimulating. I also want to thank Prof. Dr. Suraiya Faroqhi and Prof. Dr. Jo Vansteenbergen, for their expert suggestions. My colleagues of the History Department have also been supportive by letting me share my ideas in development during research meetings at the department, lunches and visits to the pub. I would also like to sincerely thank the scholars who shared their ideas and expertise with me: Dimitris Kastritsis, Feridun Emecen, David Wrisley, Güneş Işıksel, Deborah Boucayannis, Kadir Dede, Kristof d’Hulster, Xavier Baecke and many others. -

The Coins of the Later Ilkhanids

THE COINS OF THE LATER ILKHANIDS : A TYPOLOGICAL ANALYSIS 1 BY SHEILA S. BLAIR Ghazan Khan was undoubtedly the most brilliant of the Ilkhanid rulers of Persia: not only a commander and statesman, he was also a linguist, architect and bibliophile. One of his most lasting contribu- tions was the reorganization of Iran's financial system. Upon his accession to the throne, the economy was in total chaos: his prede- cessor Gaykhatf's stop-gap issue of paper money to fill an empty treasury had been a fiasco 2), and the civil wars among Gaykhatu, Baydu, and Ghazan had done nothing to restore trade or confidence in the economy. Under the direction of his vizier Rashid al-Din, Ghazan delivered an edict ordering the standardization of the coinage in weight, purity, and type 3). Ghazan's standard double-dirham became the basis of Iran's monetary system for the next century. At varying intervals, however, the standard type was changed: a new shape cartouche was introduced, with slight variations in legend. These new types were sometimes issued at a modified weight standard. This paper will analyze the successive standard issues of Ghazan and his two successors, Uljaytu and Abu Said, in order to show when and why these new types were introduced. Following a des- cription of the successive types 4), the changes will be explained through 296 an investigation of the metrology and a correlation of these changes in type with economic and political history. Another article will pursue the problem of mint organization and regionalization within this standard imperial system 5).