The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 702.21 Kb

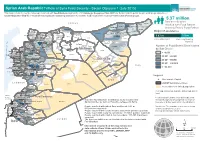

Syrian Arab Republic: Whole of Syria Food Security - Sector Objective 1 (July 2015) This map reflects the number of people reached with Food Baskets against the 2015 Strategic Response Plan (SRP) for Syrian Arab Republic as part of Strategic Objective 2 Sector Objective 1(SO 1) : Provide life-saving and life sustaining assistance to meet the food needs of the most vulnerable crisis affected groups. 5.37 million Total beneficiaries T u rr kk e yy Al Malika Jawadiyah E reached with Food Basket Amuda Quamishli Qahtaniyyeh Darbasiyah (monthly Family Food Ration) Ain al Arab Ya'robiyah Lower Shyookh Bulbul Jarablus Raju Ghandorah Tal Hmis Origin of assistance Sharan Tell Abiad Be'r Al-Hulo Al-Wardeyyeh Ar-Ra'ee Ras Al Ain Ma'btali A'zazSuran Tal Tamer Menbij Al-Hasakeh Sheikh El-Hadid Aghtrin Tall Refaat Al-HaPsakeh 1.5 m Afrin A'rima Sarin 3.87 m Jandairis Mare' Abu Qalqal Ein Issa Suluk Al Bab Nabul Hole From within Syria From neighbouring Daret AzzaHaritan Tadaf a Aleppo Harim Dana Rasm Haram El-Imam e Qourqeena JebelP Saman countries Eastern Kwaires Areesheh S Salqin Atareb Ar-Raqqa Dayr Hafir Jurneyyeh n Maaret Tamsrin As Safira Karama Shadadah a ArmaIndaz leTebftnaz Maskana Number of Food Basket Beneficiaries Darkosh ZarbahHadher Banan P e IdlePbBennsh n Kiseb Ar-Raqqa Jisr-Ash-Shugur Saraqab Hajeb by Sub District a Ariha Al-Thawrah Kisreh r Qastal MaafRabee'aBadama Markada Abul ThohurTall Ed-daman Maadan r Kansaba Ehsem e Ein El-Bayda Ziyara Ma'arrat An Nu'man Al-Khafsa < 10,000 t Khanaser Mansura Sabka i Al HafaSalanfa Sanjar Lattakia -

I. Turkish Gendarmerie Fires Directly at Asylum-Seekers

Casualties on the Syrian Border continue to fall by the www.stj-sy.org Turkish Gendarmerie Casualties on the Syrian Border Continue to Fall by the Turkish Gendarmerie At least 12 asylum-seekers (men and women) killed and others injured by the Turkish Gendarmerie in July, August, September and October 2019 Page | 2 Casualties on the Syrian Border continue to fall by the www.stj-sy.org Turkish Gendarmerie At least, 12 men and women shot dead by the Turkish border guards (Gendarmerie) while attempting to access into Turkey illegally during July, August, September and October 2019. Turkey continues violating its international obligations, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights, by firing live bullets, beating, abusing and insulting asylum-seekers on the Syria-Turkey border. These violations have not ceased, despite dozens of appeals and many human rights reports that documented these acts since the outset of the asylum process to Turkey in 2012.1 According to victims’ relatives and witnesses who managed to access into Turkey, the Gendarmerie forces always fire live bullets on asylum-seekers and beats, tortures, insults, and uses those they caught in forced labor, and deport them back to Syria. STJ recommends that the Turkish government and the international community need to take serious steps that reduce violations against asylum seekers fleeing death, as violence and military operations continue to threaten Syrians and push them to search for a safe place to save their lives, knowing that Turkey has closed its borders with Syria since mid- August 2015, after the International Federation concluded a controversial immigration deal with Turkey that would prevent the flow of refugees to Europe.2 For the present report, STJ meets a medical worker and an asylum seeker tortured by the Turkish Gendarmerie as well as three relatives of victims who have been recently shot dead by Turkish border guards. -

QRCS Delivers Medical Aid to Hospitals in Aleppo, Idlib

QRCS Delivers Medical Aid to Hospitals in Aleppo, Idlib May 3rd, 2016 ― Doha: Qatar Red Crescent Society (QRCS) is proceeding with its support of the medical sector in Syria, by providing medications, medical equipment, and fuel to help health facilities absorb the increasing numbers of injuries, amid deteriorating health conditions countrywide due to the conflict. Lately, QRCS personnel in Syria procured 30,960 liters of fuel to operate power generators at the surgical hospital in Aqrabat, Idlib countryside. These $17,956 supplies will serve the town's 100,000 population and 70,000 internally displaced people (IDPs). In coordination with the Health Directorate in Idlib, QRCS is operating and supporting the hospital with fuel, medications, medical consumables, and operational costs. Working with a capacity of 60 beds and four operating rooms, the hospital is specialized in orthopedics and reconstructive procedures, in addition to general medicine and dermatology clinics. In western Aleppo countryside, QRCS personnel delivered medical consumables and serums worth $2,365 to the health center of Kafarnaha, to help reduce the pressure on the center's resources, as it is located near to the clash frontlines. Earlier, a needs assessment was done to identify the workload and shortfalls, and accordingly, the needed types of supplies were provided to serve around 1,500 patients from the local community and IDPs. In relation to its $200,000 immediate relief intervention launched last week, QRCS is providing medical supplies, fuel, and food aid; operating AlSakhour health center for 100,000 beneficiaries in Aleppo City, at a cost of $185,000; securing strategic medical stock for the Health Directorate; providing the municipal council with six water tankers to deliver drinking water to 350,000 inhabitants at a cost of $250,000; arranging for more five tankers at a cost of $500,000; providing 1,850 medical kits, 28,000 liters of fuel, and water purification pills; and supplying $80,000 worth of food aid. -

Component 1A the Age of the Crusades, C1071-1204

History Paper 1A (A-level) Specimen Question Paper Question 02 Student 1 Specimen Answer and Commentary V1.1 12/08/15 Strictly confidential Specimen Answer plus commentary The following student response is intended to illustrate approaches to assessment. This response has not been completed under timed examination conditions. It is not intended to be viewed as a ‘model’ answer and the marking has not been subject to the usual standardisation process. Paper 1A (A-level): Specimen question paper 02 To what extent was effective leadership responsible for the establishment of the crusader states in the years 1096 to 1154? (25 marks) Student Response There are a number of reasons why the crusader states were successfully established in the years 1097-1154, but by far the most important of these reasons was that they had effective leadership, for the most part. From the outset, the crusader states relied on effective leadership. For example, on the First Crusade, the leadership of Bohemond of Taranto was pivotal both at the Battle of Dorylaeum and the Siege of Antioch. Even after the First Crusade, when the crusader states were “little more than a loose network of dispersed outposts” (Asbridge), the leadership of Baldwin I of Jerusalem was important in establishing this nascent kingdom. Through a clever use of clemency mixed with ruthlessness, Baldwin was able to take Arsuf, Caesarea, and Acre in quick succession by 1104. As there was a real threat to Baldwin’s kingdom from Egypt, he had to not only pacify the region between Egypt and Syria, but also create a loyal and subservient aristocracy, which he did. -

Political Economy Report English F

P a g e | 1 P a g e | 2 P a g e | 3 THE POLITICAL ECONOMY And ITS SOCIAL RAMIFICATIONS IN THREE SYRIAN CITIES: TARTOUS, Qamishli and Azaz Economic developments and humanitarian aid throughout the years of the conflict, and their effect on the value chains of different products and their interrelation with economic, political and administrative factors. January 2021 P a g e | 4 KEY MESSAGES • The three studied cities are located in different areas of control: Tartous is under the existing Syrian authority, Azaz is within the “Euphrates Shield” areas controlled by Turkey and the armed “opposition” factions loyal to it, and most of Qamishli is under the authority of the “Syrian Democratic Forces” and the “Self-Administration” emanating from it. Each of these regions has its own characteristics in terms of the "political war economy". • After ten years of conflict, the political economy in Syria today differs significantly from its pre-conflict conditions due to specific mechanisms that resulted from the war, the actual division of the country, and unilateral measures (sanctions). • An economic and financial crisis had hit all regions of Syria in 2020, in line with the Lebanese crisis. This led to a significant collapse in the exchange rate of the Syrian pound and a significant increase in inflation. This crisis destabilized the networks of production and marketing of goods and services, within each area of control and between these areas, and then the crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated this deterioration. • This crisis affected the living conditions of the population. The monthly minimum survival expenditure basket (SMEB) defined by aid agencies for an individual amounted to 45 working days of salaries for an unskilled worker in Azaz, 37 days in Tartous and 22 days in Qamishli. -

THE CRUSADES Toward the End of the 11Th Century

THE MIDDLE AGES: THE CRUSADES Toward the end of the 11th century (1000’s A.D), the Catholic Church began to authorize military expeditions, or Crusades, to expel Muslim “infidels” from the Holy Land!!! Crusaders, who wore red crosses on their coats to advertise their status, believed that their service would guarantee the remission of their sins and ensure that they could spend all eternity in Heaven. (They also received more worldly rewards, such as papal protection of their property and forgiveness of some kinds of loan payments.) ‘Papal’ = Relating to The Catholic Pope (Catholic Pope Pictured Left <<<) The Crusades began in 1095, when Pope Urban summoned a Christian army to fight its way to Jerusalem, and continued on and off until the end of the 15th century (1400’s A.D). No one “won” the Crusades; in fact, many thousands of people from both sides lost their lives. They did make ordinary Catholics across Christendom feel like they had a common purpose, and they inspired waves of religious enthusiasm among people who might otherwise have felt alienated from the official Church. They also exposed Crusaders to Islamic literature, science and technology–exposure that would have a lasting effect on European intellectual life. GET THE INFIDELS (Non-Muslims)!!!! >>>> <<<“GET THE MUSLIMS!!!!” Muslims From The Middle East VS, European Christians WHAT WERE THE CRUSADES? By the end of the 11th century, Western Europe had emerged as a significant power in its own right, though it still lagged behind other Mediterranean civilizations, such as that of the Byzantine Empire (formerly the eastern half of the Roman Empire) and the Islamic Empire of the Middle East and North Africa. -

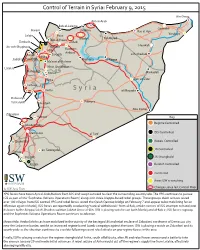

Control of Terrain in Syria: February 9, 2015

Control of Terrain in Syria: February 9, 2015 Ain-Diwar Ayn al-Arab Bab al-Salama Qamishli Harem Jarablus Ras al-Ayn Yarubiya Salqin Azaz Tal Abyad Bab al-Hawa Manbij Darkush al-Bab Jisr ash-Shughour Aleppo Hasakah Idlib Kuweiris Airbase Kasab Saraqib ash-Shadadi Ariha Jabal al-Zawiyah Maskana ar-Raqqa Ma’arat al-Nu’man Latakia Khan Sheikhoun Mahardeh Morek Markadeh Hama Deir ez-Zour Tartous Homs S y r i a al-Mayadin Dabussiya Palmyra Tal Kalakh Jussiyeh Abu Kamal Zabadani Yabrud Key Regime Controlled Jdaidet-Yabus ISIS Controlled Damascus al-Tanf Quneitra Rebels Controlled as-Suwayda JN Controlled Deraa Nassib JN Stronghold Jizzah Kurdish Controlled Contested Areas ISW is watching Changes since last Control Map by ISW Syria Team YPG forces have taken Ayn al-Arab/Kobani from ISIS and swept outward to clear the surrounding countryside. The YPG continues to pursue ISIS as part of the “Euphrates Volcano Operations Room,” along with three Aleppo-based rebel groups. These groups claim to have seized over 100 villages from ISIS control. YPG and rebel forces seized the Qarah Qawzaq bridge on February 7 and appear to be mobilizing for an oensive against Manbij. ISIS forces are reportedly conducting “tactical withdrawals” from al-Bab, amidst rumors of ISIS attempts to hand over its bases to the Aleppo Sala Jihadist coalition Jabhat Ansar al-Din. ISW is placing watches on both Manbij and al-Bab as ISIS forces regroup and the Euphrates Volcano Operations Room continues to advance. Meanwhile, Hezbollah forces have mobilized in the vicinity of the besieged JN and rebel enclave of Zabadani, northwest of Damascus city near the Lebanese border, amidst an increased regime barrel bomb campaign against the town. -

A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2014 A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E. Tobias Osterhaug Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Osterhaug, Tobias, "A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E." (2014). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 25. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/25 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Tobias Osterhaug History 499/Honors 402 A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E. Introduction: The first Crusade, a massive and unprecedented undertaking in the western world, differed from the majority of subsequent crusades into the Holy Land in an important way: it contained no royalty and was undertaken with very little direct support from the ruling families of Western Europe. This aspect of the crusade led to the development of sophisticated hierarchies and vassalages among the knights who led the crusade. These relationships culminated in the formation of the Crusader States, Latin outposts in the Levant surrounded by Muslim states, and populated primarily by non-Catholic or non-Christian peoples. Despite the difficulties engendered by this situation, the Crusader States managed to maintain control over the Holy Land for much of the twelfth century, and, to a lesser degree, for several decades after the Fall of Jerusalem in 1187 to Saladin. -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.Long.T65

Cambridge University Press 0521017475 - The Leper King and his Heirs: Baldwin IV and the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem Bernard Hamilton Index More information Index Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad, 80 Alexius II Comnenus, Byzantine emperor, al-Muqta®, 68 138, 148, 160, 174 al-Mustadi, 159 Alexius the protosebastus, 160 al-Nazir,159,171,184 Alfonso II, king of Aragon, 118 Abul' Khair, Baldwin IV's riding master, 28 Alice, princess of Antioch, 24, 41 Abu Shamah, historian, 17±18, 136 Alix of Lorraine, 140 Abu Sulayman Dawud, Baldwin IV's doctor, Almoravids of Majorca, 170 28, 251 Alwa, Nubian Christian kingdom of, 69 Acre, 46 n. 14, 53, 60, 119, 122, 127±8, 147, Amalric,kingofJerusalem,1,6,9,23±40, 192, 197, 203±4, 217±18, 223, 227, 243 43,45n.4,60,63±4,84±7,89±92, leprosaria, 257 95, 97, 107, 110, 116, 119±20, 125, 129, siege of (1189±91), 137, 196 n. 40, 231±2 149, 162, 173, 220, 249±51 Adam of St George of Labaene, 35 relations with Byzantium, 64±7, 111±13, Adela, queen of France, 30, 140, 149±50 127 Aden, 80, 182 relations with the kingdom of Sicily, 75±6, al-Adil, Saladin's brother, 87, 98, 141, 181, 81±2 183±4, 195, 201 relations with the Order of Assassins, 70±5 giraffe of, 202 Amalric of Nesle, Latin patriarch of al-Afdal, Saladin's son, 227±8 Jerusalem, 23, 35±6, 42, 114, 122, 133, Agnes of ChaÃtillon, queen of Hungary, 105 138±9, 144, 162 AgnesofCourtenay,2,9,23±6,33±4,84,89, Ambroise, Estoire de la guerre sainte,12 95±8,103±6,152±3,158,160,163, Andronicus Angelus, Byzantine envoy, 127, 167±8, 188, 194, 214 n. -

Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul Area Snelders, B

Identity and Christian-Muslim interaction : medieval art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul area Snelders, B. Citation Snelders, B. (2010, September 1). Identity and Christian-Muslim interaction : medieval art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul area. Peeters, Leuven. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15917 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15917 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 2. The Syrian Orthodox in their Historical and Artistic Settings 2.1 Northern Mesopotamia and Mosul The blossoming of ‘Syrian Orthodox art’ during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries is mainly attested for Northern Mesopotamia. At the time, Northern Mesopotamia was commonly known as the Jazira (Arabic for ‘island’), a geographic entity encompassing roughly the territory which is located between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, and lies north of Baghdad and south of Lake Van. 1 In ecclesiastical terms, this region is called Athur (Assyria). 2 Early Islamic historians and geographers distinguished three different districts: Diyar Mudar, Diyar Bakr, and Diyar Rabi cah. Today, these districts correspond more or less to eastern Syria, south-eastern Turkey, and northern Iraq, respectively. Mosul was the capital of the Diyar Rabi cah district, which ‘extended north from Takrit along both banks of the Tigris to the tributary Ba caynatha river a few kilometres north of Jazirat ibn cUmar (modern Cizre) and westwards along the southern slopes of the Tur cAbdin as far as the western limits of the Khabur Basin’. -

A Cultural Heritage in Alanya: Alara (Down) Bath

Uluslararası Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi / The Journal of International Social Research Cilt: 11 Sayı: 60 Yıl: 2018 Volume: 11 Issue: 60 Year: 2018 www.sosyalarastirmalar.co m Issn: 1307 - 9581 http://dx.doi.org/ 10.17719/jisr.2018.2807 A CULTURAL HERITAGE IN ALANYA: ALARA (DOWN) BATH Murat KAR ADEMİR Abstract Alara Castle and Medieval Settlement, which is located in the boundaries of Antalya province, Alanya district a nd Okurcalar town, began to deve lop soon after Sultan Alaeddin I conquered the region. The region consists of a down c ity loc ated on out skirt of sleep sloped castle and Alara Valley. Alara is located on the trade route pretecting its significance throughout the Middle Ages. The region has a strategic importance on the roads of Anatolia from the North to the South by its locatio n. Although the castle which was used in the periods of Rome, Byzantine, Cilicia, Armenian Kingdom, Seljukian and Ottoman became a small settlement in the cou rse of time, its main period was in the 13th century in medieval age after it was captured by the Turks. Down city primarily consists of structural units such as khan, bridge, mosque and bath. On the edge of creek, down bath is located outside of expanding fortress walls, lo ts in plants and its remains are almost entirely below ground. Because of it s location, the bath building was damaged badly during the overflow of the Alara stream, also a part of buildin g was able to survive. In this paper, a general evaluation will be done about architectural features of the building which was named “Down Bath” and had been unearthed by excavation during Alara Archeological Excavations. -

Cry Havoc Règles Fr 20/07/17 10:50 Page1

ager historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 20/07/17 10:50 Page1 HISTORY & SCENARIOS ager historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 20/07/17 10:50 Page2 © Buxeria & Historic’One éditions - 2017 - v1.0 ager historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 20/07/17 10:50 Page3 SELJUK SULTANATE OF RUM Konya COUNTY OF EDESSA Sis PRINCIPALITY OF ARMENIAN CILICIA Edessa Tarsus Turbessel Harran BYZANTINE EMPIRE Antioch Aleppo PRINCIPALITY OF ANTIOCH Emirate of Shaïzar Isma'ili COUNTY OF GRAND SELJUK TRIPOLI EMPIRE Damascus Acre DAMASCUS F THE MIDDLE EAST KINGDOM IN 1135 TE O OF between the First JERUSALEM and Second Crusades Jerusalem EMIRA N EW S FATIMID 0 150 km CALIPHATE ager historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 20/07/17 10:43 Page1 History The Normans in Northern Syria in the 12th Century 1. Historical background Three Normans distinguished themselVes during the First Crusade: Robert Curthose, Duke of NormandY and eldest son of William the Conqueror 1 Whose actions Were decisiVe at the battle of DorYlea in 1197, Bohemond of Taranto, the eldest son of Robert Guiscard 2, and his nepheW Tancred, Who led one of the assaults upon the Walls of Jerusalem in 1099. Before participating in the crusade, Bohemond had been passed oVer bY his Younger half-brother Roger Borsa as Duke of Puglia and Calabria on the death of his father in 1085. Far from being motiVated bY religious sentiment like GodfreY of Bouillon, the crusade Was for him just another occasion to Wage War against his perennial enemY, BYZantium, and to carVe out his oWn state in the HolY Land.