Political Economy Report English F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 702.21 Kb

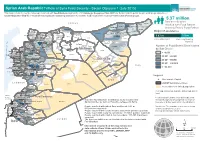

Syrian Arab Republic: Whole of Syria Food Security - Sector Objective 1 (July 2015) This map reflects the number of people reached with Food Baskets against the 2015 Strategic Response Plan (SRP) for Syrian Arab Republic as part of Strategic Objective 2 Sector Objective 1(SO 1) : Provide life-saving and life sustaining assistance to meet the food needs of the most vulnerable crisis affected groups. 5.37 million Total beneficiaries T u rr kk e yy Al Malika Jawadiyah E reached with Food Basket Amuda Quamishli Qahtaniyyeh Darbasiyah (monthly Family Food Ration) Ain al Arab Ya'robiyah Lower Shyookh Bulbul Jarablus Raju Ghandorah Tal Hmis Origin of assistance Sharan Tell Abiad Be'r Al-Hulo Al-Wardeyyeh Ar-Ra'ee Ras Al Ain Ma'btali A'zazSuran Tal Tamer Menbij Al-Hasakeh Sheikh El-Hadid Aghtrin Tall Refaat Al-HaPsakeh 1.5 m Afrin A'rima Sarin 3.87 m Jandairis Mare' Abu Qalqal Ein Issa Suluk Al Bab Nabul Hole From within Syria From neighbouring Daret AzzaHaritan Tadaf a Aleppo Harim Dana Rasm Haram El-Imam e Qourqeena JebelP Saman countries Eastern Kwaires Areesheh S Salqin Atareb Ar-Raqqa Dayr Hafir Jurneyyeh n Maaret Tamsrin As Safira Karama Shadadah a ArmaIndaz leTebftnaz Maskana Number of Food Basket Beneficiaries Darkosh ZarbahHadher Banan P e IdlePbBennsh n Kiseb Ar-Raqqa Jisr-Ash-Shugur Saraqab Hajeb by Sub District a Ariha Al-Thawrah Kisreh r Qastal MaafRabee'aBadama Markada Abul ThohurTall Ed-daman Maadan r Kansaba Ehsem e Ein El-Bayda Ziyara Ma'arrat An Nu'man Al-Khafsa < 10,000 t Khanaser Mansura Sabka i Al HafaSalanfa Sanjar Lattakia -

ISCACH (Beirut 2015) International Syrian Congress on Archaeology and Cultural Heritage

ISCACH (Beirut 2015) International Syrian Congress on Archaeology and Cultural Heritage PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 3‐6 DECEMBER 2015 GEFINOR ROTANA HOTEL BEIRUT, LEBANON ISCACH (Beirut 2015) International Syrian Congress on Archaeology and Cultural Heritage PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 3‐6 DECEMBER 2015 GEFINOR ROTANA HOTEL BEIRUT, LEBANON © The ISCACH 2015 Organizing Committee, Beirut Lebanon All rights reserved. No reproduction without permission. Title: ISCASH (International Syrian Congress on Archaeology and Cultural Heritage) 2015 Beirut: Program and Abstracts Published by the ISCACH 2015 Organizing Committee and the Archaeological Institute of Kashihara, Nara Published Year: December 2015 Printed in Japan This publication was printed by the generous support of the Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan ISCACH (Beirut 2015) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction……….……………………………………………………….....................................3 List of Organizing Committee ............................................................................4 Program Summary .............................................................................................5 Program .............................................................................................................7 List of Posters ................................................................................................. 14 Poster Abstracts.............................................................................................. 17 Presentation Abstracts Day 1: 3rd December ............................................................................ -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013

United Nations S/2012/401 Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013 Original: English Identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, and 1 and 4 June 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 3 June 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 13-20354 (E) 170113 210113 *1320354* S/2012/401 Annex to the identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Sunday, 3 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 2/6/2012, from 1600 hours until 2000 hours, an armed terrorist group exchanged fire with law enforcement forces after the group attacked the forces between the orchards of Duma and Hirista. 2. On 2/6/2012 at 2315 hours, an armed terrorist group detonated an explosive device in a civilian vehicle near the primary school on Jawlan Street, Fadl quarter, Judaydat Artuz, wounding the car’s driver and damaging the car. -

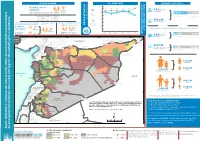

G Secto R Objective 1: Improve the Fo Od Security Status of Assessed Foo D Insecure Peo Ple by Emergency Humanita

PEOPLE IN NEED PEOPLE IN NEED SO1 RESPONSE JANUARY 2017 CYCLE 8 7m Food & Livelihood 9 7 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m million Assistance Million 5.01 ORIGIN Food Basket 6 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) - 2017 SO1 6.16m 3.35 M 1.631.79 MM 5.96m 5.8m 5.89m 3.35m 1.63m Target 5.45m 5 From within Syria From neighbouring September 2015 8.7 Million 5.01m countries June 2016 9.4 Million WHOLE OF SYRIA 4 September 2016 9.0 Million 459,299 Cash and Voucher 3 LIFE SUSTAINING AND LIFE SAVING OVERALL TARGET JAN 2017 PLAN RESPONSE Reached FOOD ASSISTANCE (SO1) TARGET SO1 Food Basket, Cash & Voucher BENEFICIARIES Beneficiaries Food Basket, 2 Cash & Voucher - 7 Additionally, Bread - Flour and Ready to Eat Rations were also Provided 5.01 1 life sustaining MODALITIES AND Million 9 Million Million 0 Emergency 2 (72%) of SO1 Target AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC JAN BENEFICIARIES REACHED BY Response Million 291,911 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) - 2017 2.08million 1.79 M 36°0'0"E 38°0'0"E 40°0'0"E 42°0'0"E From within Syria From neighbouring Bread-Flour countries 7 Cizre- 1 g! 0 Kiziltepe-Ad Nusaybin-Al 2 T U R K E Y Darbasiyah Qamishli Peshkabour T U R K E Y g! g! g! Ayn al Arab Ceylanpinar-Ras Al Ayn Al Yaroubiya Islahiye Karkamis-Jarabulus g! - Rabiaa 635,144 g! g! Akcakale-Tall g! Bab As Abiad g! Emergency Response with 11,700 580,838 Salama Cobanbey g! Ready to Eat Ration From within Syria From neighbouring g! g! countries Reyhanli - A L --H A S A K E H Bab al Hawa g! N A L E P P O " A L E P P O 0 Karbeyaz ' 0 Yayladagi ° g! A R - R A Q Q A 6 g! A R - R A Q Q A 3 1,193,251 Women IID L E B L A T T A K IIA 1,374,537 2,567,787 Girls Female Beneciaries H A M A Mediterranean D E II R -- E Z -- Z O R Sea T A R T O U S II R A Q T A R T O U S Al Arida g! 1,081,796 Abu Men H O M S Kamal-Khutaylah H O M S g! 1,360,733 L E B A N O N 2,442,530 Boys N " Male Beneciaries 0 ' 0 ° 4 3 Masnaa-Jdeidet Yabous *Note: SADD is based on ratio of 49:51 for male/female due to lack of consistent data across UNDOF g! partners. -

The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson

The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 1 Copyright Statement This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed to the owner of the Intellectual Property Rights. 2 Abstract The Latin principality of Antioch was founded during the First Crusade (1095-1099), and survived for 170 years until its destruction by the Mamluks in 1268. This thesis offers the first full assessment of the thirteenth century principality of Antioch since the publication of Claude Cahen’s La Syrie du nord à l’époque des croisades et la principauté franque d’Antioche in 1940. It examines the Latin principality from its devastation by Saladin in 1188 until the fall of Antioch eighty years later, with a particular focus on its relationship with the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia. This thesis shows how the fate of the two states was closely intertwined for much of this period. The failure of the principality to recover from the major territorial losses it suffered in 1188 can be partly explained by the threat posed by the Cilician Armenians in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. -

February 2019 Fig

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN February 2019 Fig. AIDoctors providing physiotherapy services Turkey Cross Border Fig. AIDoctors providing Physical Therapy sessions. Emergency type: complex emergency Reporting period: 01.02.2019 to 28.02.2019 13.2 MILLION* 2.9 MILLION* 3.58 MILLION 3** ATTACKS PEOPLE IN NEED OF HEALTH PIN IN SYRIAN REFUGGES AGAINST HEALTH CARE HEALTH ASSISTANCE NWS HRP2019 IN TURKEY (**JAN-FEB 2019) (A* figures are for the Whole of Syria HRP 2019 (All figures are for the Whole of Syria) HIGHLIGHTS GAZIANTEP HEALTH CLUSTER The funds suspension from the governments of 116 HEALTH CLUSTER MEMBERS Germany and France in humanitarian activities in MEDICINES DELIVERED1 the health sector was lifted for some NGOs and TREATMENT COURSES FOR COMMON 460,000 the programs with humanitarian activities will DISEASES resume. Although suspension was lifted, the FUNCTIONAL HEALTH FACILITIES HERAMS NGOs must adhere to several additional FUNCTIONING FIXED PRIMARY HEALTH measures to allow full resumption of the 173 CARE FACILITIES humanitarian activities. 85 FUNCTIONING HOSPITALS The Azaz Mental Health Asylum Hospital will stop 80 MOBILE CLINICS operating end of February 2019. The hospital, HEALTH SERVICES2 supported by PAC, is currently funded by King 905,502 CONSULTATIONS Salman Foundation. The mental health patients 9,320 DELIVERIES ASSISTED BY A SKILLED of this hospital should be transported to Aleppo ATTENDANT or Damascus City. An Exit Strategy/Transfer plan 8,489 REFERRALS is not clear yet but been develop. 977,744 MEDICAL PROCEDURES th On 26 February, local sources reported that the 37,310 TRAUMA CASES SUPPORTED SSG issued a new circular that all the NGOs 2,387 NEW CONFLICT RELATED TRAUMA CASES vehicles and ambulances must get a mission VACCINATION order from the SSG to be able to cross from Idleb 8,264 CHILDREN AGED ˂5 VACCINATED3 to Afrin and Northern Aleppo. -

Citadel of Masyaf

GUIDEBOOK English version TheThe CCitadelitadel ofof MMasyafasyaf Description, History, Site Plan & Visitor Tour Description, History, Site Plan & Visitor Tour Frontispiece: The Arabic inscription above the basalt lintel of the monumental doorway into the palace in the Inner Castle. This The inscription is dated to 1226 AD, and lists the names of “Alaa ad-Dunia of wa ad-Din Muhammad, Citadel son of Hasan, son of Muhammad, son of Hasan (may Allah grant him eternal power); under the rule of Lord Kamal ad- Dunia wa ad-Din al-Hasan, son of Masa’ud (may Allah extend his power)”. Masyaf Opposite: Detail of this inscription. Text by Haytham Hasan The Aga Khan Trust for Culture is publishing this guidebook in cooperation with the Syrian Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums as part of a programme for the Contents revitalisation of the Citadel of Masyaf. Introduction 5 The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Geneva, Switzerland (www.akdn.org) History 7 © 2008 by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission of the publisher. Printed in Syria. Site Plan 24 Visitor Tour 26 ISBN: 978-2-940212-06-4 Introduction The Citadel of Masyaf Located in central-western Syria, the town of Masyaf nestles on an eastern slope of the Syrian coastal mountains, 500 metres above sea level and 45 kilometres from the city of Hama. Seasonal streams flow to the north and south of the city and continue down to join the Sarout River, a tributary of the Orontes. -

5.28 M 874,814

Syrian Arab Republic: Whole of Syria Food Security Sector - Sector Objective 1 (March Plan - 2016) This map reflects the number of people reached with Life Saving Activities against the 2016 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) as part of Strategic Objective 1 Sector Objective 1(SO 1) : Provide emergency response capacity, lifesaving, and life sustaining assistance to the most vulnerable crisis affected people, including people with specific needs. 5.28 m Jawadiyah Total beneficiaries planned T U R K E Y Al Malika Quamishli Qahtaniyyeh E with food baskets (monthly Amuda 1. Rasm Haram El-Imam Darbasiyah 2. Rabee'a 3. Eastern Kwaires Lower Ain al Ya'robiyah family food ration), cash & 4. Armanaz Jarablus Shyookh Arab Bulbul 5. Kafr Takharim Al-Hasakeh Raju Sharan Ghandorah Tell Be'r Al-Hulo Tal Hmis voucher food assistance Suran Ras Al Tal ! Ar-Ra'ee Abiad Al-Wardeyyeh Ma'btali A'z!az Ain Tamer Sheikh Aghtrin Tall Menbij P Origin of assistance El-Hadid Afrin A'rima Sarin Al-Hasakeh Re!faat Abu Ein Issa Suluk Al Bab Qalqal Hole Jandairis Na!bul Mare' Daret ! Tadaf 3.2 m 2.07 m Dan!a ! Aleppo Har!im Azza 1 P! Haritan Ar-Raqqa ! !Maaret Atareb Jebel 3 Dayr Areesheh From within Syria From neighbouring Salqin!5 ! Tamsrin Saman Hafir Jurneyyeh 4 ! Zarbah countries ! ! As Safira Ar-Raqqa Shadadah Darko!sh Idle! b Hadher Karama ! Bennsh Banan Maskana P Kiseb Janudiyeh Idleb!PSarm!in Badama Mhambal ! Hajeb Qastal 2 ! ! Saraqab Abul Al-Thawrah Markada Jisr-Ash-Shugur Ariha Al-Khafsa Maadan Kisreh March-Plan vs SO1 Target Maaf ! Ma'arrat Thohur Kansaba -

COVID-19 Rapid Assessment Government of Syria Controlled Areas

Humanitarian Needs GOS 31 March, 2020 Assessment Programme COVID-19 Rapid Assessment Government of Syria Controlled Areas This report provides an overview of the response to the COVID-19 virus in GoS controlled areas. Data collection was undertaken at the sub-district level on Saturday 28 and Sunday 29 March 2020, via face-to-face key informant interviews. Mitigation Measures TURKEY No Yes Additional hand washing facilities in the camps / collective shelters 194 Menbij Nabul Al Bab Closure of public spaces Haritan 19 175 Rasm Haram El-Imam Jebel Saman Eastern Kwaires Dayr Hafir As-Safira ZarbahHadher Maskana Banan Communication on COVID-19 risk 6 188 Kasab Hajeb Saraqab Al-Khafsa Qastal MaafRabee'a Abul ThohurTall Ed-daman Maadan Kansaba Ziyara Ein El-Bayda Ma'arrat An Nu'man Khanaser Sabka Al-HaffaSalanfa Mansura Lattakia Kafr Nobol Sanjar Mzair'a Heish Tabni Disinfection campaign 68 126 Hanadi Shat-ha Madiq Castle FakhuraAl-Qardaha Tamanaah Khan Shaykun Hamra As-Suqaylabiyah IRAQ Jablah Kafr Zeita As-Saan Suran Qteilbiyyeh Tell Salhib Deir-ez-Zor Khasham Dalyeh Muhradah Anaza Jeb Ramleh Banyas Saboura Distribution of soap/disinfectant 189 5 Qadmous Hama Oqeirbat Rawda Masyaf As-Salamiyeh Muhasan Sheikh Badr Soda Khawabi Ein Halaqim Harbanifse Eastern Bari Sibbeh Oj Ar-Rastan Tartous Dreikish Talbiseh Al Mayadin Arwad HawashQabu Taldu Safita Ein Elniser Jeb Ej-Jarrah Kherbet Elma'aza Nasra Shin Al Makhrim Ashara Health screening for new IDPs 191 3 HameidiyyehSafsafa Homs SisniyyehTall KalakhHadideh Sokhneh Kherbet Tin Noor Jalaa Kareemeh -

National Museum of Aleppo As a Model)

Strategies for reconstructing and restructuring of museums in post-war places (National Museum of Aleppo as a Model) A dissertation submitted at the Faculty of Philosophy and History at the University of Bern for the doctoral degree by: Mohamad Fakhro (Idlib – Syria) 20/02/2020 Prof. Dr. Mirko Novák, Institut für Archäologische Wissenschaften der Universität Bern and Dr. Lutz Martin, Stellvertretender Direktor, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin Fakhro. Mohamad Hutmatten Str.12 D-79639 Grenzach-Wyhlen Bern, 25.11.2019 Original document saved on the web server of the University Library of Bern This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No derivative works 2.5 Switzerland licence. To see the licence go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/ or write to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California 94105, USA Copyright Notice This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No derivative works 2.5 Switzerland. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/ You are free: to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work Under the following conditions: Attribution. You must give the original author credit. Non-Commercial. You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No derivative works. You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.. For any reuse or distribution, you must take clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Nothing in this license impairs or restricts the author’s moral rights according to Swiss law. -

Operation Euphrates Shield: Implementation and Lessons Learned Lessons and Implementation Shield: Euphrates Operation

REPORT REPORT OPERATION EUPHRATES SHIELD: IMPLEMENTATION OPERATION AND LESSONS LEARNED EUPHRATES MURAT YEŞILTAŞ, MERVE SEREN, NECDET ÖZÇELIK The report presents a one-year assessment of the Operation Eu- SHIELD phrates Shield (OES) launched on August 24, 2016 and concluded on March 31, 2017 and examines Turkey’s future road map against the backdrop of the developments in Syria. IMPLEMENTATION AND In the first section, the report analyzes the security environment that paved the way for OES. In the second section, it scrutinizes the mili- tary and tactical dimensions and the course of the operation, while LESSONS LEARNED in the third section, it concentrates on Turkey’s efforts to establish stability in the territories cleansed of DAESH during and after OES. In the fourth section, the report investigates military and political MURAT YEŞILTAŞ, MERVE SEREN, NECDET ÖZÇELIK lessons that can be learned from OES, while in the fifth section, it draws attention to challenges to Turkey’s strategic preferences and alternatives - particularly in the north of Syria - by concentrating on the course of events after OES. OPERATION EUPHRATES SHIELD: IMPLEMENTATION AND LESSONS LEARNED LESSONS AND IMPLEMENTATION SHIELD: EUPHRATES OPERATION ANKARA • ISTANBUL • WASHINGTON D.C. • KAHIRE OPERATION EUPHRATES SHIELD IMPLEMENTATION AND LESSONS LEARNED COPYRIGHT © 2017 by SETA All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, without permission in writing from the publishers. SETA Publications 97 ISBN: 978-975-2459-39-7 Layout: Erkan Söğüt Print: Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık A.Ş., İstanbul SETA | FOUNDATION FOR POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RESEARCH Nenehatun Caddesi No: 66 GOP Çankaya 06700 Ankara TURKEY Tel: +90 312.551 21 00 | Fax :+90 312.551 21 90 www.setav.org | [email protected] | @setavakfi SETA | İstanbul Defterdar Mh. -

Note by the Technical Secretariat

OPCW Technical Secretariat S/1677/2018 10 October 2018 Original: ENGLISH NOTE BY THE TECHNICAL SECRETARIAT SUMMARY UPDATE OF THE ACTIVITIES CARRIED OUT BY THE OPCW FACT-FINDING MISSION IN SYRIA UPDATE 1. This summary provides an update on the activities of the OPCW Fact-Finding Mission in Syria (FFM) since the Eighty-Eighth Session of the Executive Council. 2. The FFM has deployed in order to gather relevant facts. All deployments and movements of the FFM took place with all necessary authorisations, including from the United Nations Department of Safety and Security. 3. The FFM received Note Verbale No. 88 (dated 20 September 2017) from the Syrian Arab Republic, referring to an allegation of use of an unknown toxic gas in Qalib al-Thawr, Al-Salimayah on 9 August 2017. The Syrian Arab Republic also addressed to the FFM Notes Verbales No. 103 (dated 26 October 2017), No. 116 (dated 10 November 2017), and No. 128 (dated 4 December 2017), requesting the OPCW to investigate two incidents that occurred in Khirbat Masasinah, Hama Governorate on 7 July and 4 August 2017. Furthermore, Note Verbale No. 127 (dated 24 November 2017) refers to an incident in Al-Balil, Souran, Hama Governorate on 8 November 2017. 4. After reviewing the information gathered by the FFM and provided by the authorities of the Syrian Arab Republic in regard to the incidents mentioned in paragraph 3 above, the FFM deployed in December 2017. Subsequently, the FFM identified a number of issues requiring clarification. This formed the basis for the FFM’s deployment in September 2018, during which the FFM discussed certain issues with the Syrian Arab Republic and received clarifications through various documents, as well as written explanations from the Syrian authorities.