Operation Euphrates Shield: Implementation and Lessons Learned Lessons and Implementation Shield: Euphrates Operation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-ISIS States by Dr

Background Report V: 14 March 2017 Post-ISIS States by Dr. Gina Lennox Kurdish Lobby Australia Email: [email protected] T: (02) 649 40079 (Dr. Gina Lennox) Mobile: 0433 227 977 (Zirian Fatah) PO Box 181, Strathfield, NSW, 2135 Website: www.kurdishlobbyaustralia.com Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3 Iraq .............................................................................................................................. 3 Government of Iraq (GoI).................................................................................................... 3 Mosul offensive .................................................................................................................. 5 IDP/Refugee crisis ..................................................................................................................... 9 Turkey’s intentions in Nineveh ................................................................................................. 9 Post-ISIS Nineveh .................................................................................................................... 10 Kirkuk ............................................................................................................................... 10 ISIS threats elsewhere ....................................................................................................... 11 Kurdistan Region of Iraq ................................................................................................... -

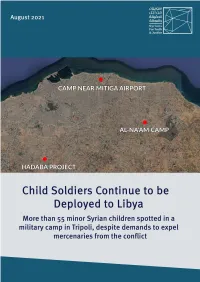

Child Soldiers Continue to Be Deployed to Libya

www.stj-sy.org Child Soldiers Continue to be Deployed to Libya More than 55 minor Syrian children spotted in a military camp in Tripoli, despite demands to expel mercenaries from the conflict Page | 2 www.stj-sy.org Despite an October 2020 ceasefire agreement and repeated international calls to expel all foreign forces and mercenaries from the Libyan conflict, recruitment operations continue to enlist and transfer Syrian mercenaries into Libya – including children under the age of 18. In 2021, the recruitments have largely been carried out by Russia and Turkey. In July 2021, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) obtained new testimonies on the deployment of new groups of children to Tripoli, Libya’s capital, since March 2021. Notably, we heard from a 16-year-old child soldier, a fighter in the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division, and a medical worker who treated a number of recruited children in a hospital in Tripoli. We contacted sources via phone and through encrypted online applications. Sources confirmed the spread of 55 new Syrian child recruits in areas overseen by the Government of National Accord (GNA), including makeshift camp near Mitiga International Airport, al-Sahbah camp, Hadaba project and al-Na’am camp. Image 1 – A map of locations where Syrian child soldiers have been observed in Libya. Military Groups Recruiting Children Sources provided STJ with the names of military groups formed by the opposition-Syrian National Army (SNA) who are confirmed to have children serving among their ranks in Libya. The groups include the Auxiliary Forces/al-Quwat al-Radifa, Front and Alert Units, and Special Intrusion Units. -

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (Wos) Task Force

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (WoS) Task Force December 2020 updates Governorate summary 19K In December 2020, the humanitarian community tracked some 43,000 IDP Aleppo 17K movements across Syria, similar to numbers tracked in November. As in 25K preceding months, most IDP movements were concentrated in northwest 21K Idleb 13K Syria, with 92 percent occurring within and between Aleppo and Idleb 15K governorates. 800 Ar-Raqqa 800 At the sub-district level, Dana in Idleb governorate and Ghandorah, Bulbul and 800 Sharan in Aleppo governorate each received around 2,800 IDP movements in 443 Lattakia 380 December. Afrin sub-district in Aleppo governorate received around 2,700 830 movements while Maaret Tamsrin sub-district in Idleb governorate and Raju 320 Tartous 230 71% sub-district in Aleppo governorate each received some 2,500 IDP movements. 611 of IDP arrivals At the community level, Tal Aghbar - Tal Elagher community in Aleppo 438 occurred within Hama 43 governorate received the largest number of displaced people, with around 350 governorate 2,000 movements in December, followed by some 1,000 IDP movements 245 received by Afrin community in Aleppo governorate. Around 800 IDP Homs 105 122 movements were received by Sheikh Bahr community in Aleppo governorate 0 Deir-ez-Zor and Ar-Raqqa city in Ar-Raqqa governorate, and Lattakia city in Lattakia 0 IDPs departure from governorate 290 n governorate, Koknaya community in Idleb governorate and Azaz community (includes displacement from locations within 248 governorate and to outside) in Aleppo governorate each received some 600 IDP movements this month. -

1 Towards a Visualisation of the Zionist Sabra 1930-1967 JC Torday

Towards a visualisation of the Zionist Sabra 1930-1967 JC Torday A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Brighton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2014 1 Declaration I declare that the research contained in this thesis, unless otherwise formally indicated within the text, is the original work of the author. The thesis has not been previously submitted to this or any other university for a degree, and does not incorporate any material already submitted for a degree. Signed JC Torday Dated February 2014 2 Abstract (page 3) Introduction (page 5) Research Approach (page 16) Arab Villages and colonisation (page 24) Cultural Memory and collective memory (page 31) Chapter 1: Theoretical considerations and influences on Zionist photographs (page 39) Critics of and theories about photographs (page 39) Influences on Israeli photography (page 45) Chapter 2: Zionism and colonialism (page 71) The rise of Zionism (page 71) The Iron Wall (page 76) A view from 1947 (page 81) Zionism and anti-Semitism (page 84) Zionism and Fascism (page 87) Zionism and nationalism (page 90) Colonialism (page 93) Colonialism and Zionism (97) Three waves of Jewish immigration (page 102) The Sharon Plan (page 105) Colonialism and photographs (108) Biblical archaeology (page 113) Ethnocentric myth (page 119) Chapter 3: Photography in the Holy Land and beyond (page 121) Beginnings (page 121) Photographs in the Yishuv (page 130) Photographs in Israel (page 147) Chapter 4: The Sabra (page 174) The myth of the Sabra (page -

The Syrian National Council: a Victorious Opposition?

THE INSTITUTE FOR MIDDLE EAST STUDIES IMES CAPSTONE PAPER SERIES THE SYRIAN NATIONAL COUNCIL: A VICTORIOUS OPPOSITION? JARED MARKLAND KRITTIKA LALWANEY MAY 2012 THE INSTITUTE FOR MIDDLE EAST STUDIES THE ELLIOTT SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY COPYRIGHT OF THE AUTHOR(S), 2012 THE SYRIAN NATIONAL COUNCIL: A VICTORIOUS OPPOSITION? Jared Markland & Krittika Lalwaney Introduction The Syrian National Council (SNC) emerged as an opposition movement representing the democratic uprisings in Syria calling for regime change. The Assad regime’s forceful measures against Syrians have delegitimized the government and empowered the revolution. The success of the revolution, in overthrowing the regime hinges on the Syrian opposition’s ability to overcome its deficiencies. This paper analyzes the performance of the SNC by determining SNC success or failure to launch a successful opposition movement against the regime. The SNC’s probability of success in the overthrow of the regime is contingent on its ability to unify internally, obtain financial capacity, establish international recognition, and build internal popular support. Methodology The methods used to examine the prospects for success of the SNC as a viable opposition movement consist of comparative case studies and qualitative field research. We examined four case studies, including Nicaragua, Libya, El Salvador and Guatemala. These cases establish a set of core factors necessary for an opposition movement to succeed. The utilization of these factors allows us to create a comparative assessment of the overall performance of the SNC. Our qualitative fieldwork entailed a total of 32 interviews with current SNC members, Syrian activists, refugees, Free Syrian Army members, academic experts, and government officials. -

Syria: "Torture Was My Punishment": Abductions, Torture and Summary

‘TORTURE WAS MY PUNISHMENT’ ABDUCTIONS, TORTURE AND SUMMARY KILLINGS UNDER ARMED GROUP RULE IN ALEPPO AND IDLEB, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Cover photo: Armed group fighters prepare to launch a rocket in the Saif al-Dawla district of the Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons northern Syrian city of Aleppo, on 21 April 2013. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/4227/2016 July 2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 METHODOLOGY 7 1. BACKGROUND 9 1.1 Armed group rule in Aleppo and Idleb 9 1.2 Violations by other actors 13 2. ABDUCTIONS 15 2.1 Journalists and media activists 15 2.2 Lawyers, political activists and others 18 2.3 Children 21 2.4 Minorities 22 3. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Spring 2014 Commencement Program

TE TA UN S E ST TH AT I F E V A O O E L F A DITAT DEUS N A E R R S I O Z T S O A N Z E I A R I T G R Y A 1912 1885 ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT AND CONVOCATION PROGRAM Spring 2014 May 12 - 16, 2014 THE NATIONAL ANTHEM THE STAR SPANGLED BANNER O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light, What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming? Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight O’er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming? And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there. O say does that Star-Spangled Banner yet wave O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave? ALMA MATER ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Where the bold saguaros Raise their arms on high, Praying strength for brave tomorrows From the western sky; Where eternal mountains Kneel at sunset’s gate, Here we hail thee, Alma Mater, Arizona State. —Hopkins-Dresskell MAROON AND GOLD Fight, Devils down the field Fight with your might and don’t ever yield Long may our colors outshine all others Echo from the buttes, Give em’ hell Devils! Cheer, cheer for A-S-U! Fight for the old Maroon For it’s Hail! Hail! The gang’s all here And it’s onward to victory! Students whose names appear in this program have completed degree requirements. -

Political Economy Report English F

P a g e | 1 P a g e | 2 P a g e | 3 THE POLITICAL ECONOMY And ITS SOCIAL RAMIFICATIONS IN THREE SYRIAN CITIES: TARTOUS, Qamishli and Azaz Economic developments and humanitarian aid throughout the years of the conflict, and their effect on the value chains of different products and their interrelation with economic, political and administrative factors. January 2021 P a g e | 4 KEY MESSAGES • The three studied cities are located in different areas of control: Tartous is under the existing Syrian authority, Azaz is within the “Euphrates Shield” areas controlled by Turkey and the armed “opposition” factions loyal to it, and most of Qamishli is under the authority of the “Syrian Democratic Forces” and the “Self-Administration” emanating from it. Each of these regions has its own characteristics in terms of the "political war economy". • After ten years of conflict, the political economy in Syria today differs significantly from its pre-conflict conditions due to specific mechanisms that resulted from the war, the actual division of the country, and unilateral measures (sanctions). • An economic and financial crisis had hit all regions of Syria in 2020, in line with the Lebanese crisis. This led to a significant collapse in the exchange rate of the Syrian pound and a significant increase in inflation. This crisis destabilized the networks of production and marketing of goods and services, within each area of control and between these areas, and then the crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated this deterioration. • This crisis affected the living conditions of the population. The monthly minimum survival expenditure basket (SMEB) defined by aid agencies for an individual amounted to 45 working days of salaries for an unskilled worker in Azaz, 37 days in Tartous and 22 days in Qamishli. -

Turkey Orchestrating Violence Beyond Borders

TURKEY: ORCHESTRATING VIOLENCE BEYOND BORDERS By RETHINKING Mohammed Sami POLICY BRIEF Middle East Analyst January 2020 SECURITY IN 2020 SERIES INTRODUCTION KEY TAKEAWAYS In late December 2019, the Tripoli based-UN backed- • Turkey continues its deployment of Government of National Accord (GNA) appealed for Syrian rebels to Libya. Turkey to intervene in Libya. As a response, the Turkish rd Parliament held an emergency session on January 3 , • Syrian rebels are deployed with attractive 2020, and voted to authorize President Recep Tayep Er- salaries to fight in Libya. dogan to deploy Turkish troops to Libya. Soon after, the deployment of troops materialized. However, not only • The selection process of rebels was based were Turkish military forces deployed but Syrian rebels on a specific criterion. from northern Syria too. In recent months, Turkey’s military activities, such as its expatriation of Syrian ref- • Private military contractors played a role in ugees to their war-torn country and the deployment of preparing and deploying Syrian rebels to Turkish-backed Syrian rebels to fight along the GNA in Libya. Libya, pose serious risks of escalation in the region. While the European Union remains committed to fund its Facility for Refugees in Turkey, these activities re- local activists, partners, and local population, this pol- quire greater scrutiny on its financial support provided icy brief explores Turkey’s deployment of Syrian rebels to Turkey. Based on first-hand data collected through to Libya, its deportation of refugees to Syria and ques- interviews conducted by the BIC research team with tions the implications these developments have on the EU’s Facility for Refugees in Turkey. -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013

United Nations S/2012/401 Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013 Original: English Identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, and 1 and 4 June 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 3 June 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 13-20354 (E) 170113 210113 *1320354* S/2012/401 Annex to the identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Sunday, 3 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 2/6/2012, from 1600 hours until 2000 hours, an armed terrorist group exchanged fire with law enforcement forces after the group attacked the forces between the orchards of Duma and Hirista. 2. On 2/6/2012 at 2315 hours, an armed terrorist group detonated an explosive device in a civilian vehicle near the primary school on Jawlan Street, Fadl quarter, Judaydat Artuz, wounding the car’s driver and damaging the car. -

Syrian Armed Opposition Powerbrokers

March 2016 Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS Cover: A rebel fighter of the Southern Front of the Free Syrian Army gestures while standing with his fellow fighter near their weapons at the front line in the north-west countryside of Deraa March 3, 2015. Syrian government forces have taken control of villages in southern Syria, state media said on Saturday, part of a campaign they started this month against insurgents posing one of the biggest remaining threats to Damascus. Picture taken March 3, 2015. REUTERS/Stringer All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2016 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2016 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jennifer Cafarella is the Evans Hanson Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War where she focuses on the Syrian Civil War and opposition groups. Her research focuses particularly on the al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al Nusra and their military capabilities, modes of governance, and long-term strategic vision. She is the author of Likely Courses of Action in the Syrian Civil War: June-December 2015, and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria: An Islamic Emirate for al-Qaeda.