Malcolm Barber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conquest of Arsuf by Baybars: Political and Military Aspects (MSR IX.1, 2005)

REUVEN AMITAI THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY OF JERUSALEM The Conquest of Arsu≠f by Baybars: Political and Military Aspects* A modern-day visitor to Arsu≠f1 cannot help but be struck by the neatly arranged piles of stones from siege machines found at the site. This ordering, of course, represents the labors of contemporary archeologists and their assistants to gather the numerous but scattered stones. Yet, in spite of the recent nature of this "installation," these heaps are clear, if mute, evidence of the great efforts of the Mamluks led by Sultan Baybars (1260–77) to conquer the fortified city from the Franks in 1265. This conquest, as well as its political background and its aftermath, will be the subjects of the present article, which can also be seen as a case-study of Mamluk siege warfare. The immediate backdrop to the Mamluk attack against Arsu≠f was the events of the preceding weeks. At the end of 1264, while Baybars was hunting in the Egyptian countryside, he received reports that the Mongols were heading in force for the Mamluk border fortress of al-B|rah along the Euphrates, today in south- eastern Turkey. The sultan quickly returned to Cairo, and ordered the immediate dispatch of advanced light forces, which were followed by a more organized, but still relatively small, force under the command of the senior amir (officer) Ughan Samm al-Mawt ("the Elixir of Death"), and then by a third corps, together with © Middle East Documentation Center. The University of Chicago. *I would like to thank Prof. Israel Roll of Tel Aviv University, who conducted the excavations at the site, and was most helpful when he showed us the site. -

Was There a Custom of Distributing the Booty in the Crusades of the Thirteenth Century?

Benjámin Borbás WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? MA Thesis in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies Central European University Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2019 WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection WAS THERE A CUSTOM OF DISTRIBUTING THE BOOTY IN THE CRUSADES OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY? by Benjámin Borbás (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, -

History of the Crusades. Episode 103 the Last Crusades. Hello Again

History of the Crusades. Episode 103 The Last Crusades. Hello again. Last week, things didn't go so well for the Latin Christians in the Middle East, with an entire Crusader state, the Principality of Antioch, being effectively wiped off the map following an invasion by the Egyptian Mamluk Sultan Baibars. The Latin Christians of Europe had been viewing events in the Holy Land with concern for some time, and with the fall of Antioch, it was obvious that some urgent assistance was required. More specifically, what was needed of course, was another Crusade. As far back as August 1266 Pope Clement IV had begun to call for a new Crusade. England had been wracked by civil war, but that had come to an end in 1265, and with King Louis IX’s ambitious brother Charles of Anjou securing for himself the Sicilian crown in 1266, the attentions of the people in Europe could finally focus on problems in the Middle East. King Louis of France, now aged in his early fifties, jumped at the chance to redeem the failure of his ill-fated previous Crusade, and on the 25th of March 1267 once again made a public vow to take up the Cross. Also raising their hands to mount a Crusade were Lord Edward of England and King James I of Aragon. Lord Edward was the son of the aging King Henry III of England, and would later become King Edward I. Against his father's wishes. Lord Edward made his Crusading vow in 1268, and many of the noblemen of England, keen to put the trauma of the recent civil war behind them, followed his example. -

Throughout Anglo-Saxon and Norman Times, Many People – Not Just Rich Kings and Bishops

THE CRUSADES: A FIGHT IN THE NAME OF GOD. Timeline: The First Crusade, 1095-1101; The Second Crusade, 1145-47; The Third Crusade, 1188-92; The Fourth Crusade, 1204; The Fifth Crusade, 1217; The Sixth Crusade, 1228-29, 1239; The Seventh Crusade, 1249-52; The Eighth Crusade, 1270. Throughout Anglo-Saxon and Norman times, many people – not just rich kings and bishops - went to the Holy Land on a Pilgrimage, despite the long and dangerous journey – which often took seven or eight years! When the Turks conquered the Middle East this was seen as a major threat to Christians. [a] Motives for the Crusades. 1095, Pope Urban II. An accursed race has violently invaded the lands of the Christians. They have destroyed the churches of God or taken them for their own religion. Jerusalem is now held captive by the enemies of Christ, subject to those who do not know God – the worship of the heathen….. He who makes this holy pilgrimage shall wear the sign of the cross of the Lord on his forehead or on his breast….. If you are killed your sins will be pardoned….let those who have been fighting against their own brothers now fight lawfully against the barbarians…. A French crusader writes to his wife, 1098. My dear wife, I now have twice as much silver, gold and other riches as I had when I set off on this crusade…….. A French crusader writes to his wife, 1190. Alas, my darling! It breaks my heart to leave you, but I must go to the Holy land. -

THE CRUSADES Toward the End of the 11Th Century

THE MIDDLE AGES: THE CRUSADES Toward the end of the 11th century (1000’s A.D), the Catholic Church began to authorize military expeditions, or Crusades, to expel Muslim “infidels” from the Holy Land!!! Crusaders, who wore red crosses on their coats to advertise their status, believed that their service would guarantee the remission of their sins and ensure that they could spend all eternity in Heaven. (They also received more worldly rewards, such as papal protection of their property and forgiveness of some kinds of loan payments.) ‘Papal’ = Relating to The Catholic Pope (Catholic Pope Pictured Left <<<) The Crusades began in 1095, when Pope Urban summoned a Christian army to fight its way to Jerusalem, and continued on and off until the end of the 15th century (1400’s A.D). No one “won” the Crusades; in fact, many thousands of people from both sides lost their lives. They did make ordinary Catholics across Christendom feel like they had a common purpose, and they inspired waves of religious enthusiasm among people who might otherwise have felt alienated from the official Church. They also exposed Crusaders to Islamic literature, science and technology–exposure that would have a lasting effect on European intellectual life. GET THE INFIDELS (Non-Muslims)!!!! >>>> <<<“GET THE MUSLIMS!!!!” Muslims From The Middle East VS, European Christians WHAT WERE THE CRUSADES? By the end of the 11th century, Western Europe had emerged as a significant power in its own right, though it still lagged behind other Mediterranean civilizations, such as that of the Byzantine Empire (formerly the eastern half of the Roman Empire) and the Islamic Empire of the Middle East and North Africa. -

The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217-1218

IACOBVS REVIST A DE ESTUDIOS JACOBEOS Y MEDIEVALES C@/llOj. ~1)OI I 1 ' I'0 ' cerrcrzo I~n esrrrotos r~i corrnrro n I santiago I ' s a t'1 Cl fJ r1 n 13-14 SAHACiVN (LEON) - 2002 CENTRO DE ESTVDIOS DEL CAMINO DE SANTIACiO The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217-1218 Laszlo VESZPREMY Instituto Historico Militar de Hungria Resumen: Las relaciones entre los cruzados y el Reino de Hungria en el siglo XIII son tratadas en la presente investigacion desde la perspectiva de los hungaros, Igualmente se analiza la politica del rey cruzado magiar Andres Il en et contexto de los Balcanes y del Imperio de Oriente. Este parece haber pretendido al propio trono bizantino, debido a su matrimonio con la hija del Emperador latino de Constantinopla. Ello fue uno de los moviles de la Quinta Cruzada que dirigio rey Andres con el beneplacito del Papado. El trabajo ofre- ce una vision de conjunto de esta Cruzada y del itinerario del rey Andres, quien volvio desengafiado a su Reino. Summary: The main subject matter of this research is an appro- ach to Hungary, during the reign of Andrew Il, and its participation in the Fifth Crusade. To achieve such a goal a well supported study of king Andrew's ambitions in the Balkan region as in the Bizantine Empire is depicted. His marriage with a daughter of the Latin Emperor of Constantinople seems to indicate the origin of his pre- tensions. It also explains the support of the Roman Catholic Church to this Crusade, as well as it offers a detailed description of king Andrew's itinerary in Holy Land. -

Read Transcript

History of the Crusades. Episode 101 Baibars Attacks. Hello again. Last week we saw the rise to power of Rukn al-Din Baibars. Sultan Baibars’ territory now stretches all the way from his capital in Cairo to northern Syria. With his realm secured and consolidated, Baibars sets his sights on his two enemies in the region, the Mongols and the Franks. Now, most Muslim leaders in the past had been content to arrange peace treaties with the Crusader states, leaving them to maintain their presence in the Holy Land. Not Baibars. He viewed the busy commercial port cities in the Crusader states as centers which could be incorporated into Muslim territory. The Latin Christians controlled a strip of fertile land running down the coast of the Mediterranean. Baibars wanted to drive them from this strip of land. With Hulagu’s Mongol armies still a potent force, Baibars knew he had to bide his time. Instead, in the early 1260s, Baibars looked further afield and tried his hand at international diplomacy. Unsurprisingly, the first person he reached out to was King Manfred of Sicily, the illegitimate son of Emperor Frederick II who had deposed young Conradin as ruler of Sicily and Acre. The Egyptians had enjoyed a close relationship with Emperor Frederick, and Manfred seemed of a similar disposition. Hoping to encourage the growing split between Manfred and the Papacy, and perhaps reduce the chance of Europe mounting another Crusade in aid of the beleaguered Latin Christians of the Crusader states, Baibars sent an envoy to Sicily bearing gifts for King Manfred. -

Re-Examining Usama Ibn Munqidh's Knowledge of "Frankish": a Case Study of Medieval Bilingualism During the Crusades

Re-examining Usama ibn Munqidh's Knowledge of "Frankish": A Case Study of Medieval Bilingualism during the Crusades Bogdan C. Smarandache The Medieval Globe, Volume 3, Issue 1, 2017, pp. 47-85 (Article) Published by Arc Humanities Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/758505 [ Access provided at 27 Sep 2021 14:33 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] RE-EXAMINING USAMA IBN MUNQIDH’S KNOWLEDGE OF “FRANKISH”: A CASE STUDY OF MEDIEVAL BILINGUALISM DURING THE CRUSADES BOGDAN C. SMARANDACHE a Syrian gentleman, warriorpoet, Muslim amir, and fāris (488–584/1095–1188)—described variously as uignorancesaMa Iofbn the Munq FrankishIdh language in his Kitab al-iʿtibar (The Book of Learning (knight)—professes by Example), when recounting one of his childhood memories. Born to the Arab dynasty of the Banu Munqidh, who ruled the castle and hinterland of Shayzar on the Aṣi (or Orontes) River, Usama had grown up in close proximity to the Frankish Principality of Antioch. In the decade following the First Crusade (488–492/1095–1099), the Banu Munqidh and their Frankish neighbours engaged begun his military training. Recalling that time decades later, he remembers that in periodic raids and skirmishes. By that time, Usama was a youth and might have Tancred, the Christian ruler of Antioch (d. 506/1112), had granted a guarantee unfortunate young cavalier was actually heading into a trap that cost him his right of safe-conduct to a skilled horseman from Shayzar, a man named Hasanun. (The Ifranjī eye, but he had trusted in Tancred’s good will.) After describing the initial negotia 1 tion of safe-conduct, Usama adds that “they speak only in Frankish ( ) so we had no idea what they were saying.” To date, Usama’s statement has deterred scholars from investigating the small number of Frankish loanwords preserved in his book, it appears to leave extent of his second language acquisition in greater depth. -

Maria Paleologina and the Il-Khanate of Persia. a Byzantine Princess in an Empire Between Islam and Christendom

MARIA PALEOLOGINA AND THE IL-KHANATE OF PERSIA. A BYZANTINE PRINCESS IN AN EMPIRE BETWEEN ISLAM AND CHRISTENDOM MARÍA ISABEL CABRERA RAMOS UNIVERSIDAD DE GRANADA SpaIN Date of receipt: 26th of January, 2016 Final date of acceptance: 12th of July, 2016 ABSTRACT In the 13th century Persia, dominated by the Mongols, a Byzantine princess, Maria Paleologina, stood out greatly in the court of Abaqa Khan, her husband. The Il-Khanate of Persia was then an empire precariously balanced between Islam, dominant in its territories and Christianity that was prevailing in its court and in the diplomatic relations. The role of Maria, a fervent Christian, was decisive in her husband’s policy and in that of any of his successors. Her figure deserves a detailed study and that is what we propose in this paper. KEYWORDS Maria Paleologina, Il-khanate of Persia, Abaqa, Michel VIII, Mongols. CapitaLIA VERBA Maria Paleologa, Ilkhanatus Persiae, Abaqa, Michael VIII, Mongoles. IMAGO TEMPORIS. MEDIUM AEVUM, XI (2017): 217-231 / ISSN 1888-3931 / DOI 10.21001/itma.2017.11.08 217 218 MARÍA ISABEL CABRERA RAMOS 1. Introduction The great expansion of Genghis Khan’s hordes to the west swept away the Islamic states and encouraged for a while the hopes of the Christian states of the East. The latter tried to ally themselves with the powerful Mongols and in this attempt they played the religion card.1 Although most of the Mongols who entered Persia, Iraq and Syria were shamanists, Nestorian Christianity exerted a strong influence among elites, especially in the court. That was why during some crucial decades for the history of the East, the Il-Khanate of Persia fluctuated between the consolidation of Christian influence and the approach to Islam, that despite the devastation brought by the Mongols in Persia,2 Iraq and Syria remained the dominant factor within the Il-khanate. -

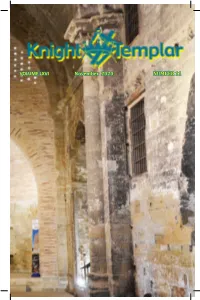

VOLUME LXVI November 2020 NUMBER 11

VOLUME LXVI November 2020 NUMBER 11 VOLUME LXVI NOVEMBER 2020 NUMBER 11 Published monthly as an official publication of the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar of the United States of America. Jeffrey N. Nelson Grand Master Jeffrey A. Bolstad Contents Grand Captain General and Publisher 325 Trestle Lane Grand Master’s Message Lewistown, MT 59457 Grand Master Jeffrey N. Nelson ..................... 4 Address changes or corrections La Forbie — The Beginning of the End and all membership activity for Frankish Outremer including deaths should be Sir Knight George L. Marshall, Jr., PGC ............. 7 reported to the recorder of the What’s the Point of a Sword? local Commandery. Please do Sir Knight John D. Barnes, PGC ...................... 12 not report them to the editor. Modern Day Chivalry Lawrence E. Tucker Sir Knight Thomas Hendrickson, PGM ........... 21 Grand Recorder Time To Move On Grand Encampment Office 5909 West Loop South, Suite 495 Reverend and Sir Knight J.B. Morris .............. 27 Bellaire, TX 77401-2402 Knights Templar Holy Land Pilgrimage Phone: (713) 349-8700 Fax: (713) 349-8710 for Sir Knights, their Ladies, and Friends ....... 30 E-mail: [email protected] Magazine materials and correspon- dence to the editor should be sent in elec- tronic form to the managing editor whose Features contact information is shown below. Materials and correspondence concern- Prelate’s Chapel ..................................................... 6 ing the Grand Commandery state supple- ments should be sent to the respective supplement editor. Focus on Chivalry .................................................. 14 John L. Palmer Leadership Notes - Delegating Effectively .............. 15 Managing Editor Post Office Box 566 The Knights Templar Eye Foundation ........5,16,17,20 Nolensville, TN 37135-0566 Phone: (615) 283-8477 Grand Commandery Supplement ......................... -

The Seventh Crusade ST

ST. MARY THE VIRGIN Sovereign Military Order of the Temple of Jerusalem The Seventh Crusade ST. MARY THE VIRGIN The Seventh Crusade First Edition 2021 Prepared by Dr. Chev. Peter L. Heineman, GOTJ, CMTJ 2020 Avenue B Council Bluffs, IA 51501 Phone 712.323.3531• www.plheineman.net Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Historical Context ....................................................................................... 2 The Campaign ........................................................................................... 3 Cyprus ............................................................................................. 4 Damietta .......................................................................................... 4 Cairo ............................................................................................... 5 Battle of Monsourah ........................................................................ 5 Battle of Fariskur ............................................................................. 6 Aftermath ................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION Seventh Crusade he Seventh Crusade (1248-1254) was led by the French king Louis IX (r. 1226-1270) who intended to conquer Egypt and take over Jerusalem; both then controlled by the Muslim Ayyubid Dynasty. Despite the initial success of capturing Damietta on the Nile, Louis' troops were defeated by the T -

Cilician Armenian Mediation in Crusader-Mongol Politics, C.1250-1350

HAYTON OF KORYKOS AND LA FLOR DES ESTOIRES: CILICIAN ARMENIAN MEDIATION IN CRUSADER-MONGOL POLITICS, C.1250-1350 by Roubina Shnorhokian A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (January, 2015) Copyright ©Roubina Shnorhokian, 2015 Abstract Hayton’s La Flor des estoires de la terre d’Orient (1307) is typically viewed by scholars as a propagandistic piece of literature, which focuses on promoting the Ilkhanid Mongols as suitable allies for a western crusade. Written at the court of Pope Clement V in Poitiers in 1307, Hayton, a Cilician Armenian prince and diplomat, was well-versed in the diplomatic exchanges between the papacy and the Ilkhanate. This dissertation will explore his complex interests in Avignon, where he served as a political and cultural intermediary, using historical narrative, geography and military expertise to persuade and inform his Latin audience of the advantages of allying with the Mongols and sending aid to Cilician Armenia. This study will pay close attention to the ways in which his worldview as a Cilician Armenian informed his perceptions. By looking at a variety of sources from Armenian, Latin, Eastern Christian, and Arab traditions, this study will show that his knowledge was drawn extensively from his inter-cultural exchanges within the Mongol Empire and Cilician Armenia’s position as a medieval crossroads. The study of his career reflects the range of contacts of the Eurasian world. ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the financial support of SSHRC, the Marjorie McLean Oliver Graduate Scholarship, OGS, and Queen’s University.