Preverbs: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intermediate German: a Grammar and Workbook / by 2 Anna Miell & Heiner Schenke 3 P

111 INTERMEDIATE GERMAN: 2 3 A GRAMMAR AND WORKBOOK 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 13 4111 5 Intermediate German is designed for learners who have achieved basic 6 proficiency and wish to progress to more complex language. Its 24 units 7 present a broad range of grammatical topics, illustrated by examples which 8 serve as models for varied exercises that follow. These exercises enable 9 the student to master the relevant grammar points. 2011 1 Features include: 2 3 • authentic German, from a range of media, used throughout the book to 4 reflect German culture, life and society 5 6 • illustrations of grammar points in English as well as German 7 • checklists at the end of each unit for consolidation 8 9 • cross-referencing to other grammar units in the book 3011 • glossary of grammatical terminology 1 2 • full answer key to all exercises 3 4 Suitable for independent learners and students on taught courses, 5 Intermediate German, together with its sister volume, Basic German, forms 6 a structured course in the essentials of German. 7 8 Anna Miell is University Lecturer in German at the University of Westminster 9 and at Trinity College of Music in Greenwich and works as a language 4011 consultant in London. Heiner Schenke is Senior Lecturer of German at the 1 University of Westminster and has published a number of language books. 2 3 41111 111 Other titles available in the Grammar Workbook series are: 2 3 Basic Cantonese 4 Intermediate Cantonese 5 Basic German 6 7 Basic Italian 8111 Basic Polish 9 Intermediate Polish 1011 1 Basic Russian 2 Intermediate -

Typological Differences Between English and Chinese Multi-Verb Constructions

Linguistics and Literature Studies 7(3): 110-115, 2019 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2019.070303 Typological Differences between English and Chinese Multi-verb Constructions Mengmeng Tang School of Foreign Studies, China University of Petroleum, China Copyright©2019 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract English and Chinese are different in the verbs in one temporal category, with fixed order and no composition of Multi-verb Constructions (MVCs), which conjunctions [25], a language phenomenon without a refer to a series of verbs appearing in a mono-clause, counterpart in English. without pauses or conjunctions. English MVCs contain a There has been a long-running discussion on Chinese finite verb which inflects with tense, combined with finite and non-finite verb distinctions (e.g., [5-8, 16-18, non-finite forms (e.g., The boss encouraged Jerry to attend 21-24, 27-30]). Although there has been a considerable the meeting). Chinese MVCs are in the form of bare verbs theoretical discussion of Chinese finiteness, no research or verbs with aspectual morphemes. From the perspective has been undertaken to date from the perspective of the of finiteness, this article analyzes the typological typological differences of semantic finiteness in Chinese differences of morphological finiteness in English and and morphological finiteness in English in MVCs. semantic finiteness in Chinese. Keywords Multi-verb Constructions, Finiteness 2. Multi-verb Constructions Verbs are the core of a sentence. Descriptive linguists and comparative syntacticians have examined the 1. -

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

Instrumentality: the Core Meaning of the Coverb Yi 以 in Classical Chinese

Proceedings of the 20th North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL-20). 2008. Volume 1. Edited by Marjorie K.M. Chan and Hana Kang. Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio State University. Pages 489-498. Instrumentality: The Core Meaning of the Coverb Yi 以 in Classical Chinese Sue-mei Wu 吳素美 Carnegie Mellon University Yi 以 is one of the most important and commonly used function words in Classical Chinese, and many researchers (e.g. Hsueh 1997, Pulleyblank 1995, Sun 1991, Wu 1994 and Wu 1997) have contributed to the discussion on yi's meanings and functions. The main issues in the current understanding of yi include its verb and coverb usages. Both usages have been thought to exhibit a range of meanings, and yi has been thought to be able to occur flexibly either before or after a verb phrase. In addition, yi is also thought to be a conjunction indicating the reason, purpose or result of an action. This study proposes that the verb yi fundamentally indicates instrumentality, and that the coverb yi, which is derived from the verb yi, still retains that fundamental notion of instrumentality. The notion of instrumentality has been extended in yi's coverb usage to indicate the means or reason by which an action occurs, or the time which an action occurs. Moreover, I will also argue that the yi phrase, when it occurs before a verb phrase, functions syntactically as a modifier to the verb phrase. When the yi phrase occurs after another verb phrase, however, the semantic emphasis has been deliberately put on the yi phrase, which then serves as the nucleus of the predicate. -

On German Verb Syntax Under Age 2

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons IRCS Technical Reports Series Institute for Research in Cognitive Science December 1994 On German Verb Syntax under Age 2 Bernhard Rohrbacher University of Pennsylvania Anne Vainikka University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports Rohrbacher, Bernhard and Vainikka, Anne, "On German Verb Syntax under Age 2" (1994). IRCS Technical Reports Series. 170. https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports/170 University of Pennsylvania Institute for Research in Cognitive Science Technical Report No. IRCS-94-24. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports/170 For more information, please contact [email protected]. On German Verb Syntax under Age 2 Abstract Previous research on early child German suggests that verb placement is mastered early on, at least around the age of two; this finding has provided support for the idea that the full syntactic tree is present from the earliest stage of syntactic development. We show that two German children around a year and a half of age already exhibit a clear distinction between finite and non-finite utterances in terms of verb placement and the distribution of empty subjects. Although their verbal paradigms are impoverished, these children clearly already have an inflectional projection (IP) in finite clauses. However, we argue against the idea that a full syntactic tree is available at this point; rather, the data support a reduced representation without a complementizer projection (CP). Furthermore, non-finite matrix clauses, common at this early stage, lack even the inflectional projection. Comments University of Pennsylvania Institute for Research in Cognitive Science Technical Report No. -

Separable Verbs in a Reusable Morphological Dictionary for German

Separable Verbs in a Reusable Morphological Dictionary for German Pius ten Hacken I & Stephan Bopp 2 l lnstitut far Informatik/ASW 2Lexicologie, Faculteit der Letteren Universit~it Basel, Petersgraben 51 Vrije Universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 CH-4051 Basel (Switzerhmd) NL- 1081 HV Amsterdam (Netherlands) email: [email protected] emaih [email protected] Abstract Separable verbs are verbs with prefixes which, depending on the syntactic context, can occur as one word written together or discontinuously. They occur in languages such as German and Dutch and constitute a problem tbr NLP because they are lexemes whose lbrms cannot always be recognized by dictionary lookup on the basis of a text word. Conventional solutions take a mixed lexical and syntactic approach. In this paper, we propose the solution offered by Word Manager, consisting of string-based recognition by means of rules of types also required for periphrastic inflection and clitics. In this way, separable verbs are dealt with as part of the dolnain of reusable lexical resources. We show how this solution compares favourably with conventional approaches. 1. The Problem (2) a. Claudia auihOrtjctzt. In German there exists a large class of verbs b. Daniel versucht zu aulh6ren. which behave like aufhOren ('stop'), The problem arises in a very similar fashion illustrated in (1). in Dutch, as the Dutch translations (3) of the (1) a. Anna glaubt, dass Bernard aufhSrt. sentences in (1) show. The only difference is ('Anna believes that Bernard stops') that the infinitive in (3c) is not written b. Claudia h6rt jetzt auf. together. ('Claudia stops now PRY') (3) a. -

Chinese: Parts of Speech

Chinese: Parts of Speech Candice Chi-Hang Cheung 1. Introduction Whether Chinese has the same parts of speech (or categories) as the Indo-European languages has been the subject of much debate. In particular, while it is generally recognized that Chinese makes a distinction between nouns and verbs, scholars’ opinions differ on the rest of the categories (see Chao 1968, Li and Thompson 1981, Zhu 1982, Xing and Ma 1992, inter alia). These differences in opinion are due partly to the scholars’ different theoretical backgrounds and partly to the use of different terminological conventions. As a result, scholars use different criteria for classifying words and different terminological conventions for labeling the categories. To address the question of whether Chinese possesses the same categories as the Indo-European languages, I will make reference to the familiar categories of the Indo-European languages whenever possible. In this chapter, I offer a comprehensive survey of the major categories in Chinese, aiming to establish the set of categories that are found both in Chinese and in the Indo-European languages, and those that are found only in Chinese. In particular, I examine the characteristic features of the major categories in Chinese and discuss in what ways they are similar to and different from the major categories in the Indo-European languages. Furthermore, I review the factors that contribute to the long-standing debate over the categorial status of adjectives, prepositions and localizers in Chinese. 2. Categories found both in Chinese and in the Indo-European languages This section introduces the categories that are found both in Chinese and in the Indo-European languages: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and conjunctions. -

Copular Constructions in Colloquial Singaporean English

Copular Constructions in Colloquial Singaporean English Honour School of Psychology, Philosophy, and Linguistics Paper C: Linguistic Project 2020 Candidate no. 1025395 Word count: 10,000 Contents List of abbreviations iv 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Language in Singapore ......................... 2 1.1.1 Early and colonial history ................... 2 1.1.2 Independence and language policies ............. 3 1.2 Colloquial Singaporean English .................... 4 1.2.1 Evolution of CSE ........................ 4 1.2.2 Status of CSE .......................... 5 1.3 Summary ................................ 6 2 Copular Constructions in Lexical-Functional Grammar 7 2.1 LFG analyses of copular constructions ................ 8 2.1.1 Single-tier analysis ....................... 9 2.1.2 Open complement double-tier analysis ............ 12 2.1.3 Closed complement double-tier analysis ........... 15 2.2 Copular constructions in SSE ..................... 17 2.3 Copular constructions in Chinese ................... 17 2.3.1 NP predicatives in Chinese .................. 17 2.3.2 AP predicatives in Chinese .................. 18 2.3.3 PP predicatives in Chinese .................. 19 2.3.4 LFG analyses of Chinese copular constructions ....... 20 2.4 Copular constructions in Malay .................... 21 2.4.1 NP predicatives in Malay ................... 21 2.4.2 AP predicatives in Malay ................... 22 2.4.3 PP predicatives in Malay ................... 22 2.4.4 LFG analyses of Malay copular constructions ........ 23 2.5 Copular constructions in CSE ..................... 23 2.6 Summary ................................ 25 ii Contents iii 3 Distribution of Copular Constructions in CSE 27 3.1 Introduction ............................... 27 3.2 Pilot study ............................... 29 3.2.1 Participants ........................... 29 3.2.2 Task ............................... 30 3.2.3 Results and discussion ..................... 31 3.3 Main study .............................. -

250 Word List

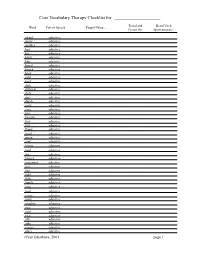

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

German Irregular Verbs Chart

GERMAN IRREGULAR VERBS CHART Infinitive Meaning Present Tense Imperfect Participle Tense (e.g. for Passive, & Perfect Tense) to… er/sie/es: ich & er/sie/es: backen bake backt backte gebacken befehlen command, order befiehlt befahl befohlen beginnen begin beginnt begann begonnen beißen bite beißt biss gebissen betrügen deceive, cheat betrügt betrog betrogen bewegen1 move bewegt bewog bewogen biegen bend, turn biegt bog (bin etc.) gebogen bieten offer, bid bietet bot geboten binden tie bindet band gebunden bitten request, ask bittet bat gebeten someone to do... blasen blow, sound bläst blies geblasen bleiben stay, remain bleibt blieb (bin etc.) geblieben braten roast brät briet gebraten brechen break bricht brach gebrochen brennen burn brennt brannte gebrannt bringen bring, take to... bringt brachte gebracht denken think denkt dachte gedacht dürfen be allowed to... darf durfte gedurft empfehlen recommend empfiehlt empfahl empfohlen erschrecken2 be frightened erschrickt erschrak (bin etc.) erschrocken essen eat3 isst aß gegessen fahren go (not on foot), fährt fuhr (bin etc.) gefahren drive fallen fall fällt fiel (bin etc.) gefallen fangen catch fängt fing gefangen finden find findet fand gefunden fliegen fly fliegt flog (bin etc.) geflogen fliehen flee, run away flieht floh (bin etc.) geflohen fließen flow fließt floss geflossen fressen eat (done by frisst fraß gefressen animals) frieren freeze, be cold friert fror (bin etc.) gefroren geben give gibt gab gegeben gedeihen flourish, prosper gedeiht gedieh (bin etc.) gediehen gehen go, walk geht ging (bin etc.) gegangen gelingen4 succeed gelingt gelang (bin etc.) gelungen gelten5 be valid, be of gilt galt gegolten worth 1 Also used as a reflexive verb, i.e. -

Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Linguistics, Program of 1981 Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ling_facpub Part of the Linguistics Commons Publication Info Published in Folia Linguistica Historica, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1981, pages 3-34. Disterheft, D. (1981). Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive. Folia Linguistica Historica, 2(1), 3-34. DOI: 10.1515/ flih.1981.2.1.3 © 1981 Societas Linguistica Europaea. This Article is brought to you by the Linguistics, Program of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foli.lAfl//ui.tfcoFolia Linguistica HfltorlcGHistorica II/III/l 'P'P.pp. 8-U3—Z4 © 800£etruSocietae lAngu,.ticaLinguistica Etlropaea.Evropaea, 1981lt)8l REMARKSBEMARKS ONON THETHE HISTORYHISTOKY OFOF THETHE INDO-EUROPEANINDO-EUROPEAN INFINITIVEINFINITIVE i DOROTHYDOROTHY DISTERHEFTDISTERHEFT I 1.1. INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION WithWith thethe exceptfonexception ofof Indo-IranianIndo-Iranian (Ur)(Hr) andand CelticCeltic allall historicalhistorical Indo-EuropeanIndo-European (IE)(IE) subgroupssubgroups havehave a morphologicalIymorphologically distinctdistinct II infinitive.Infinitive. However,However, nono singlesingle proto-formproto-form cancan bebe reconstructedreconstructed -

Navajo Verb Stem Position and the Bipartite Structure of the Navajo

678 REMARKSANDREPLIES NavajoVerb Stem Positionand the BipartiteStructure of the NavajoConjunct Sector Ken Hale TheNavajo verb stem appears at the rightmost edge of the verb word. Innumerouscases it forms a lexicalconstituent with a preverb,occur- ringat theleftmost edge of thesurface verb word, much in themanner ofDutchand German verb-particle arrangements in verb-secondfinite clauses.In Navajothe initial and finalpositions are separated by eight morphemeorder ‘ ‘slots’’ recognizedin the Athabaskan literature (and describedin detail for Navajo in Young and Morgan 1987). A phono- logicalsolution to this and a numberof otherdeep-surface disparities isexploredhere, based on theinsights of earlierworks on theNavajo verb,including Speas 1984, 1990, McDonough 1996, 2000, and Rice 1989, 2000. Keywords: verbmorphology, morphosyntactic disparity, spell-out, Navajo,Athabaskan 1Verb Stem Position TheNavajo verb stem forms asinglelexical constituent with the prefixal, particle-like category called preverb inthe Athabaskan linguistic literature (see Rice2000). However, like particle- verbcombinations in Dutchand German verb-second clauses, the parts of thisconstituent in the Navajocounterpart are separated in the surface forms ofverbal projections in syntax. In the Navajoversion of thisarrangement, the preverb occupies the leftmost position in the verb word, andthe verb stem occupies the rightmost position. TheNavajo verb in (1) canbe used to illustrate the phenomenon. The verb is segmented intoits various parts in (2), and the components are identified in slightly greater detail in (3). (1) Sila´o t’o´o´’go´o´ ch’´õ shidinõ´daøzh.(Young and Morgan 1987:283) ‘Thepoliceman jerked me outdoors (to get me out of afight).’ (2) ch’´õ sh d n-´ daøzh PreverbObject Qualifier Mode/ SubjVoice V (stem) Iwishto dedicate thisarticle totheNavajo Language Academy, asmall groupof linguists and teachers devotedto Navajolanguage research andeducation.