Bilingualism and the Latin Language J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Itinerarium Egeriae: a Retrospective Look and Preliminary Study of a New Approach to the Issue of Authorship-Provenance

Linguistics and Literature Studies 7(1): 13-21, 2019 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2019.070102 Itinerarium Egeriae: A Retrospective Look and Preliminary Study of a New Approach to the Issue of Authorship-provenance Víctor Parra-Guinaldo American University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates Copyright©2019 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract One of the most controversial questions with It. Eg.), the travelog of a pilgrim to the Holy Land respect to the Itinerarium Egeriae is its author’s provenance, (Starowleyski 1979), number in the hundreds. Some of and whether this can be determined on linguistic grounds. these, such as Fonda (1966) and Maraval (1982), provide The purpose of this paper is twofold: 1) to provide a central an excellent overview of the different aspects traditionally synopsis and account of previous relevant work that has discussed about the text. The twofold purpose of this paper been conducted on the manuscript; and 2) address one of is: 1) to provide a central synopsis of an updated2 account the most contested and controversial questions with respect of previous work in three areas that are relevant to this to whether its origin can be determined on linguistic paper, namely, the discovery of the manuscript, the date in grounds. In this paper, I revisit this conundrum by which it was originally written, and the provenance of the addressing two major flaws I find in the methodology author; and 2) address one of the most contested and employed to date: 1) the Romanisms sought after are for controversial questions with respect to the It. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Studies in Merovingian Latin Epigraphy and Documents a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Sa

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Studies in Merovingian Latin Epigraphy and Documents A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Indo-European Studies by Éloïse Lemay 2017 c Copyright by Éloïse Lemay 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Studies in Merovingian Latin Epigraphy and Documents by Éloïse Lemay Doctor of Philosophy in Indo-European Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Brent Harmon Vine, Chair This dissertation is a study of the subliterary Latin of Gaul from the 4th to the 8th centuries. The materials studied consist in epigraphic and documentary sources. The inscriptions of late antique and early medieval Trier and Clermont-Ferrand receive a statistical, philological and comparative analysis, which results in 1) fine-grained decade- by-decade mapping of phonological and morphosyntactic developments, 2) comparative discussion of forms of importance to the chronological and regional development of Vulgar Latin, and, 3) isolation of sociolectal characteristics. Particular attention is paid to the issue of inscription dating based upon linguistic grounds. This dissertation also approaches papyrus and parchment documents as material cul- ture artifacts. It studies the production, the use, and the characteristics of these docu- ments during the Merovingian period. This dissertation examines the reception that the Merovingian documents received in the later Middle Ages. This is tied to document destruction and survival, which I argue are the offshoot of two processes: deaccession and reuse. Reuse is tied to the later medieval practice of systematized forgery. Systematized forgeries, in turn, shed light upon the Merovingian originals, thanks to the very high level of systematic interplay between base (the Merovingian documents) and output documents (the forgeries). -

The Power of Latin in Ancient Rome

Activitydevelop The Power of Latin in Ancient Rome How did the spread of Latin influence power in ancient Rome? Overview Students investigate how the geographic spread of an impactful human system—language— influenced power in ancient Rome. For the complete activity with media resources, visit: http://education.nationalgeographic.org/activity/power-latin-ancient-rome/ Program Directions 1. Activate students’ prior knowledge. Ask: Have you ever been in a situation where you didn’t understand the language being spoken? Invite volunteers who are comfortable doing so to share their experiences with the class. As a class, discuss the common themes that are most likely to come up: feelings of discomfort, confusion, and not being understood (loss of power). Then ask: What would it feel like to be heavily influenced to adopt a language other than English? What would it feel like if the most popular activities and places in the United States today were conducted in or marked with the language of another, currently existing country? Explain to students that, in this activity, they will learn about how the spread of Latin influenced power in ancient Rome and consider how it impacted people in the invaded cities and towns. 2. Have students read about the spread of Latin in ancient Rome. Distribute a copy of the Latin in Ancient Rome worksheet to each student. Divide students into pairs and have pairs work together to read the passage and answer the questions in Part 1. Review the answers as a whole class. Ask: In your own words, describe Romanization. (Romanization is the spread of Roman customs, dress, activities, and language.) How was Latin different for different economic classes? (They had different versions of the language: Vulgar and Classical.) 1 of 6 How do you think the invaded cities and towns felt about switching to Roman customs and language? (Possible response: They probably felt pressured to do so, from both the government and the military, instead of a desire to do so on their own.) 3. -

Standard and Non-Standard Latin by Jerome Moran

Standard And Non-Standard Latin by Jerome Moran eaders would do well to keep in an artificial construct. Which dialect of litteras fatuum esse (‘You aren’t of our Rmind at all times the following ancient Greek, whose Latin [my italics], and bunch, and on that account you jeer at distinctions when reading this article: who is to say with confidence how the the words of poor people. We know standard/classical and non-standard; literary form of these languages you’re mad because of learning.’) native and non-native speaker; literate corresponded to the dialects that people (Petronius). and illiterate. I use ‘second’ and ‘foreign’ spoke on the streets?’ (Greenwood, atque id dicitur non in compitis tantum interchangeably of a language, as any pp. 202–3). neque in plebe volgaria … (‘And that is said distinction that may be made is not ‘… the question of language use in not only at crossroads nor among the relevant in the context of a world in the case of social groups for whom a common people …’) (Gellius). which there were no nation-states (or language is not a second language, but who quod vulgo dicitur ossum, Latine os notions of political correctness). If I are regarded as secondary users of that dicitur (‘What is called ossum in the were to prefer one to the other it would language.’ (Greenwood, p.208). language of the common people, in be ‘foreign’: native speakers of Latin … quid tibi ego videor in epistulis? nonne Latin [i.e. ‘correct’ Latin] is called os’) regarded everyone else but Greek- plebeio sermone agere tecum?… epistulas (Augustine). -

Roman Vulgar Law in Late Antiquity

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg DETLEF LIEBS Roman Vulgar Law in Late Antiquity Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Boudewijn Sirks (Hrsg.): Aspects of law in late antiquity : dedicated to A.M. Honoré on the occasion of the sixtieth year of his teaching in Oxford. Oxford: Souls College, 2008, S. 35 - 53 Roman Vulgar Law in Late Antiquity* Detlef Liebs 1. Heinrich Brunner’s ‚Römisches Vulgarrecht’ The term ‚Römisches Vulgarrecht’, in English ‚Roman vulgar law’, was coined in 1880 by the historian of Germanic law Heinrich Brunner1 (1840-1915), professor at the renowned U- niversity of Berlin. He used the term in a definite sense: the law of the Romance peoples un- der Germanic rule, and he meant: in Italy under the Lombards and in Gaul under the Franks from the sixth century AD up to the twelfth. After the western Emperor had abdicated in 476 AD there was, in Gaul and in Italy under the Lombards, no responsible authority as a source of the Roman law which continued to be applied, so that the Romance peoples were left to their own to develop their actually Roman law then in force. The Germanic rulers in general did not especially concern for it, except on some sensitive points like punishing high treason, and the authority of the east Roman Emperor did not extend to the Lombard and Frankish kingdoms with their mainly romance population, except for some cultural aspects like or- thography. Thus the Franks accepted the Byzantine ph instead of f in terms like philosophy, whereas the Italian, Spanish and Portuguese languages persisted in f as ordered by the west roman Emperor Constans about 350 AD.2 Brunner evoked the parallel of the vulgar Latin language. -

Cicero's Style

MNS-245-albrecht.qxd 03/04/2003 12:13 Page i CICERO’S STYLE MNS-245-albrecht.qxd 03/04/2003 12:13 Page ii MNEMOSYNE BIBLIOTHECA CLASSICA BATAVA COLLEGERUNT H. PINKSTER • H. S. VERSNEL D.M. SCHENKEVELD • P. H. SCHRIJVERS S.R. SLINGS BIBLIOTHECAE FASCICULOS EDENDOS CURAVIT H. PINKSTER, KLASSIEK SEMINARIUM, OUDE TURFMARKT 129, AMSTERDAM SUPPLEMENTUM DUCENTESIMUM QUADRAGESIMUM QUINTUM MICHAEL VON ALBRECHT CICERO’S STYLE MNS-245-albrecht.qxd 03/04/2003 12:13 Page iii CICERO’S STYLE A SYNOPSIS FOLLOWED BY SELECTED ANALYTIC STUDIES BY MICHAEL VON ALBRECHT BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2003 MNS-245-albrecht.qxd 03/04/2003 12:13 Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Albrecht, Michael von. Cicero’s Style: a synopsis / by Michael von Albrecht. p. cm. – (Mnemosyne, bibliotheca classica Batava. Supplementum ; 245) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 90-04-12961-8 1. Cicero, Marcus Tullius–Literary style. 2. Speeches, addresses, etc., Latin–History and criticism. 3. Latin language–Style. 4. Rhetoric, Ancient. 5. Oratory, Ancient. I. Title. II. Series. PA6357.A54 2003 875’.01–dc21 2003045375 ISSN 0169-8958 ISBN 90 04 12961 8 © Copyright 2003 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Latin Graduate Award Information • an Extinct Language from Ancient

Latin Graduate Award Information An extinct language from Ancient Rome. Evidence suggests it was first used over 2500 years ago. Latin influenced many languages, especially French, Spanish and Italian – ‘The Romance Languages’. Latin is an extinct language that was the official language of Ancient Rome. It was also written, read and spoken across the Roman Empire. Artefacts inscribed with written Latin have been found from as far back as 500BC! There were two different types Latin: Classical Latin (used in writing for the educated Romans) and Vulgar Latin (used by the common townspeople in spoken conversations). Is Latin still used today? Latin is an extinct language. This means that it is no longer spoken by anyone as a first language. However, many people study it in school. It is still useful, because it shows how society worked in past times. It also helps people understand modern words in many languages today. Spanish, French and Italian (among others) are known as ‘The Romance Languages’ and they have many similarities to Latin and to each other. Latin is still used to name technical things such as species of living things, medicine and diseases. Therefore, lots of Latin is found in Science. Latin was very important to Christianity for many centuries. It is still spoken today during some religious places and churches. It is an official language in the Vatican, where the Pope leads the Roman Catholic Church. If people in the Vatican speak different first languages, they use Latin to communicate. Is Latin like English? The Romans invaded - and settled in - Britain in AD 43. -

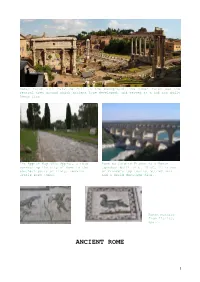

Ancient Rome Developed, and Served As a Hub for Daily Roman Life

Roman Forum with Palatine Hill in the background. The Roman Forum was the central area around which ancient Rome developed, and served as a hub for daily Roman life. The Appian Way (Via Appia), a road Pont du Gard in France is a Roman connecting the city of Rome to the aqueduct built in c. 19 BC. It is one southern parts of Italy, remains of France's top tourist attractions usable even today. and a World Heritage Site. Roman mosaics from Italica, Spain. ANCIENT ROME 1 At the height of the Roman Empire, Rome's influence reached as far north as Hadrian's Wall in present day England, as far south as Egypt, and as far east as present day Turkey and Syria. I) INTRODUCTION Ancient Rome was a civilization that started as a small agricultural community on the Italian Peninsula in the 9th century BC. In its twelve centuries of existence, Roman civilization came to dominate Western Europe and the area surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. Ancient Rome can be divided into three periods. Founded in 753 BC, it was first ruled by kings. Then, in 509 BC, a republic was established. The republic became an empire in 27 BC. That empire lasted for almost 500 years. But in the fourth century the Roman Empire was divided into two parts. Soon, the western part of the empire went into decline and its ruler was deposed by a barbarian leader in 476. The eastern part became the Byzantine Empire and lived on for another millennium. Because of the Roman Empire, Roman culture spread to Western Europe and the area surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. -

Roman Influence on Western Civilization | Philosophy 1/6/15 1:29 PM

Roman Influence on Western Civilization | Philosophy 1/6/15 1:29 PM Roman Influence on Western Civilization Western civilization is what is presently called modern or contemporary society that mainly comprises Western Europe and North America. It is believed that civilization came in through the influence of ancient cultures the two main ones being Greek and Roman. The influence by Greece was mainly by their golden age and Rome with its great Empire and Republic. Ancient Rome formed the law code much like the one used in the present time in many countries. The belief that a person is innocent until proven guilty originated from the Roman laws. Rome had senates just like the ones used today, with both upper and lower class. Ancient Rome was a civilization that expanded out of a small agricultural community. The empire was founded on the Italian peninsula in the 9th century B.C. This means that civilization has been in place for centuries. During its existence, it moved from a kingdom to an Oligarchic Republic then to an expanding Autocratic Em- pire. Roman civilization grew to dominate Southwestern Europe, Southeastern Europe and the Mediterranean area through capture and assimilation. The Roman Empire spanned a wide spread of territory and included a number of cultures. The Roman Em- pire is categorized into classical era, comprising the joining civilizations of ancient Rome and ancient Greece, jointly referred to as Creco-Roman world. The Romans were proud of their rule but they appreciated Greeks leadership in the fields of art, architecture, lit- erature and philosophy. The Romans were singular people who were once terribly cru- el but benevolently democratic. -

A History of the Sicilian Language A.A

A History of the Sicilian Language A.A. Grillo 24-Jan-2021 Sicilian is one of the many Romance Languages that evolved from Latin, the language of the Roman Empire. To say, however, only that Sicilian evolved from Latin unduly simplifies its history and development. I have tried here to relate the complexity as well as a rough timeline of its development, which adds to its richness. Most of the endnote references are Wikipedia articles and not considered primary sources, but they are easy to access with a computer and they do contain many references to primary sources for anyone wanting to research further. At its largest extent, the Roman Empire spanned from the western end of the Iberian Peninsula to ancient Babylon in the middle-east and from North Africa along the southern boundary of the Mediterranean Sea to the isle of Britannia in north-western Europe. Over this vast area, the people of the Roman courts and the scholars spoke, wrote and read classical Latin, while the commoners spoke simpler versions referred to as Vulgar Latin. Due to the great distances and slow forms of communication, these forms of Vulgar Latin varied across the empire, indeed varied even along the Italian peninsula. As these variations mixed with other locally spoken languages after the many barbarian invasions at the end of the empire, they evolved into the many languages of the lands of the former empire. For Sicilian, the non-Latin influences were present both before and after the Roman Empire. From prehistoric times, Sicily was invaded by one group after another. -

The Functional Distribution of Latin Forms in Western Europe of The

2020 International Conference on Education, Culture, Economic Management and Information Service (ECEMIS 2020) ISBN: 978-1-60595-679-4 The Functional Distribution of Latin Forms in Western Europe of the Early Middle Ages Lina Razumova1,a,*, Tsypilma Dylykova2,b, Irina Merzlyakova3,c and Lolita Sokolskikh4,d 1Department of Romance Philology, Moscow City Pedagogical University, Moscow, Russia 2Department of Theory of State and Law, Transbaikal State University, Chita, Russia 3Department of Civil Law Disciplines, Transbaikal State University, Chita, Russia 4International Department, Transbaikal State University, Chita, Russia [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] *Corresponding author Keywords: Functional distribution of idioms, Latin language, Christian Latin, Classical Latin, Vulgar Latin, Stylized Latin, Mediaeval Latin. Abstract. The article is devoted to the study of the historical dynamics of the functional distribution of Latin forms common in Western Europe in the IV–X centuries. Studying the history of the development of the Latin language as the most important source of Romance languages in the light of these developments is an extremely important phenomenon, because it is able to bring the researcher closer to understanding the issues of the emergence of Romance languages and the vitality of the Latin language after the collapse of the Roman Empire. After the fall of Rome, interest in Roman culture and classical Latin in Western European countries is still relevant. It is known that in the late period of the development of the Roman Empire, there is a differentiation of forms of classical and folk Latin, of which the vulgar, Folk Latin successfully contributed to the processes of linguistic development and the formation of new Romance languages. -

Church History Literacy St. Jerome

CHURCH HISTORY LITERACY St. Jerome Lesson 28 Biblical-Literacy.com © Copyright 2006 by W. Mark Lanier. Permission hereby granted to reprint this document in its entirety without change, with reference given, and not for financial profit. St. Jerome - The truth is so good, who needs the myth? St. Jerome: One of the 4 Western Church “Doctors” St. Ambrose St. Jerome: One of the 4 Western Church “Doctors” St. Ambrose St. Augustine St. Jerome: One of the 4 Western Church “Doctors” St. Ambrose St. Augustine St. Jerome: One of the 4 Western Church “Doctors” St. Jerome St. Ambrose St. Augustine St. Jerome: One of the 4 Western Church “Doctors” St. Jerome St. Gregory St. Ambrose St. Augustine St. Jerome: One of the 4 Western Church “Doctors” St. Jerome St. Gregory “Doctors” because of benefits to Church Birth:Birth: StridoStrido (modern(modern GrahovopoljeGrahovopolje)) Birth:Birth: StridoStrido (modern(modern GrahovopoljeGrahovopolje)) Birth:Birth: StridoStrido (modern(modern GrahovopoljeGrahovopolje)) Birth:Birth: StridoStrido (modern(modern GrahovopoljeGrahovopolje)) BornBorn aroundaround 345345 Jerome likely grew up speaking a bit of Greek and Latin “Come class, Let’s work on our Latin!” Jerome likely grew up speaking a bit of Greek and Latin “Come class, Let’s work on our Latin!” Jerome likely grew up speaking a bit of Greek and Latin “That’s Greek to me!” AtAt 12,12, JeromeJerome wentwent toto RomeRome toto studystudy LatinLatin AtAt 12,12, JeromeJerome wentwent toto RomeRome toto studystudy LatinLatin JeromeJerome studiedstudied LatinLatin