UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Studies in Merovingian Latin Epigraphy and Documents a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Sa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Itinerarium Egeriae: a Retrospective Look and Preliminary Study of a New Approach to the Issue of Authorship-Provenance

Linguistics and Literature Studies 7(1): 13-21, 2019 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2019.070102 Itinerarium Egeriae: A Retrospective Look and Preliminary Study of a New Approach to the Issue of Authorship-provenance Víctor Parra-Guinaldo American University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates Copyright©2019 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract One of the most controversial questions with It. Eg.), the travelog of a pilgrim to the Holy Land respect to the Itinerarium Egeriae is its author’s provenance, (Starowleyski 1979), number in the hundreds. Some of and whether this can be determined on linguistic grounds. these, such as Fonda (1966) and Maraval (1982), provide The purpose of this paper is twofold: 1) to provide a central an excellent overview of the different aspects traditionally synopsis and account of previous relevant work that has discussed about the text. The twofold purpose of this paper been conducted on the manuscript; and 2) address one of is: 1) to provide a central synopsis of an updated2 account the most contested and controversial questions with respect of previous work in three areas that are relevant to this to whether its origin can be determined on linguistic paper, namely, the discovery of the manuscript, the date in grounds. In this paper, I revisit this conundrum by which it was originally written, and the provenance of the addressing two major flaws I find in the methodology author; and 2) address one of the most contested and employed to date: 1) the Romanisms sought after are for controversial questions with respect to the It. -

The Use of Vulgar Language in Fiction for Young Adults Bachelor Thesis

ŠIAULIAI UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, HUMANITIES AND ART DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGE STUDIES STUDY PROGRAMME ENGLISH PHILOLOGY THE USE OF VULGAR LANGUAGE IN FICTION FOR YOUNG ADULTS BACHELOR THESIS Research Adviser: Lect. dr. Karolina Butkuvienė Student: Ieva Biliūnaitė Šiauliai, 2017 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 3 1 THE UNDERSTANDING OF VULGAR LANGUAGE ....................................................... 5 1.1 Standard and Non-standard Language .............................................................................. 5 1.2 Definition of Vulgar Language......................................................................................... 6 1.3 Vulgar Language and Other Non-standard Varieties ....................................................... 7 1.4 Types of Vulgar Language ............................................................................................. 11 1.5 Functions of Vulgar Language ....................................................................................... 14 2 THE USE OF VULGAR LANGUAGE IN MELVIN BURGESS’S NOVEL “LADY: MY LIFE AS A BITCH” ................................................................................................................. 16 2.1 Methodology of the Research ......................................................................................... 16 2.2 Bodies and their Effluvia ............................................................................................... -

Poetic Diction, Poetic Discourse and the Poetic Register

proceedings of the British Academy, 93.21-93 Poetic Diction, Poetic Discourse and the Poetic Register R. G. G. COLEMAN Summary. A number of distinctive characteristics can be iden- tified in the language used by Latin poets. To start with the lexicon, most of the words commonly cited as instances of poetic diction - ensis; fessus, meare, de, -que. -que etc. - are demonstrably archaic, having been displaced in the prose register. Archaic too are certain grammatical forms found in poetry - e.g. auldi, gen. pl. superum, agier, conticuere - and syntactic constructions like the use of simple cases for pre- I.positional phrases and of infinitives instead of the clausal structures of classical prose. Poets in all languages exploit the linguistic resources of past as well as present, but this facility is especially prominent where, as in Latin, the genre traditions positively encouraged imitatio. Some of the syntactic character- istics are influenced wholly or partly by Greek, as are other ingredients of the poetic register. The classical quantitative metres, derived from Greek, dictated the rhythmic pattern of the Latin words. Greek loan words and especially proper names - Chaoniae, Corydon, Pyrrha, Tempe, Theseus, Zephym etc. -brought exotic tones to the aural texture, often enhanced by Greek case forms. They also brought an allusive richness to their contexts. However, the most impressive charac- teristics after the metre were not dependent on foreign intrusion: the creation of imagery, often as an essential feature of a poetic argument, and the tropes of semantic transfer - metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche - were frequently deployed through common words. In fact no words were too prosaic to appear in even the highest poetic contexts, always assuming their metricality. -

Bilingualism and the Latin Language J

Cambridge University Press 0521817714 - Bilingualism and the Latin Language J. N. Adams Frontmatter More information BILINGUALISM AND THE LATIN LANGUAGE Bilingualism has become since the s one of the main themes of sociolinguistics, but there are as yet fewlarge-scale treatments of the subject specific to the ancient world. This book is the first work to deal systematically with bilingualism during a period of antiquity (the Roman period, down to about the fourth century AD) in the light of sociolinguistic discussions of bilingual issues. The general theme of the work is the nature of the contact between Latin and numerous other languages spoken in the Roman world. Among the many issues discussed three are prominent: code-switching (the practice of switching between two languages in the course of a single utterance) and its motivation, language contact as a cause of linguis- tic change, and the part played by language choice and language switching in conveying a sense of identity. J. N. ADAMSis a Senior Research Fellowof All Souls College, Oxford and a Fellowof the British Academy.He waspreviously Professor of Latin at the Universities of Manchester and Reading. In addition to articles in numerous journals, he has published five books: The Text and Language of a Vulgar Latin Chronicle (Anonymus Valesianus II) () The Vulgar Latin of the Letters of Claudius Terentianus (), The Latin Sexual Vocabulary (), Wackernagel’s Lawand the Placement of the Copula Esse in Classical Latin () and Pelagonius and Latin Veterinary Terminology in the Roman Empire (). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521817714 - Bilingualism and the Latin Language J. -

THE CULEX VIRGILIAN RATHER THAN NON-VIRQ ILIAN by John

The Culex; Virgilian rather than non-Virgilian Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Weidenschilling, J. M. (John Martin), 1893- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 15:39:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553096 THE CULEX VIRGILIAN RATHER THAN NON-VIRQ ILIAN By John Martin Weidonschilling Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the College of Letters,Arts,and Sciences,of the University of Arizona 19)0 V U l d l 381V- n c v %AHT A3HT .nH I ir oar. b ' .^1+' n ' < , "dj '' o v*r!e: •> ar rti bejj-jpi a *- * dV ut lot eeonei a? bra* i ♦ ^;. e b*j* + UilJ ni "nocit/ 3v jjo oy.; r?:? 1. Introduction* The question of authorship of the Latin poem,the Culex, has elicited considerable attention and comment during the past twenty-five years,and the subject is of special interest in this bimillenial anniversary year(1950) of the birth of Virgil. Up to the middle of the last century the Culex had been generally accepted as Virgilian. But more recently the Virgilian authorship of the poem has been questioned and even rejected by scholars of renown. Others have tried to uphold the claim of tradition. Although the controversy has pro duced numerous monographs and articles in classical peri odicals,the question of authorship still remains unsettled. -

The Power of Latin in Ancient Rome

Activitydevelop The Power of Latin in Ancient Rome How did the spread of Latin influence power in ancient Rome? Overview Students investigate how the geographic spread of an impactful human system—language— influenced power in ancient Rome. For the complete activity with media resources, visit: http://education.nationalgeographic.org/activity/power-latin-ancient-rome/ Program Directions 1. Activate students’ prior knowledge. Ask: Have you ever been in a situation where you didn’t understand the language being spoken? Invite volunteers who are comfortable doing so to share their experiences with the class. As a class, discuss the common themes that are most likely to come up: feelings of discomfort, confusion, and not being understood (loss of power). Then ask: What would it feel like to be heavily influenced to adopt a language other than English? What would it feel like if the most popular activities and places in the United States today were conducted in or marked with the language of another, currently existing country? Explain to students that, in this activity, they will learn about how the spread of Latin influenced power in ancient Rome and consider how it impacted people in the invaded cities and towns. 2. Have students read about the spread of Latin in ancient Rome. Distribute a copy of the Latin in Ancient Rome worksheet to each student. Divide students into pairs and have pairs work together to read the passage and answer the questions in Part 1. Review the answers as a whole class. Ask: In your own words, describe Romanization. (Romanization is the spread of Roman customs, dress, activities, and language.) How was Latin different for different economic classes? (They had different versions of the language: Vulgar and Classical.) 1 of 6 How do you think the invaded cities and towns felt about switching to Roman customs and language? (Possible response: They probably felt pressured to do so, from both the government and the military, instead of a desire to do so on their own.) 3. -

Standard and Non-Standard Latin by Jerome Moran

Standard And Non-Standard Latin by Jerome Moran eaders would do well to keep in an artificial construct. Which dialect of litteras fatuum esse (‘You aren’t of our Rmind at all times the following ancient Greek, whose Latin [my italics], and bunch, and on that account you jeer at distinctions when reading this article: who is to say with confidence how the the words of poor people. We know standard/classical and non-standard; literary form of these languages you’re mad because of learning.’) native and non-native speaker; literate corresponded to the dialects that people (Petronius). and illiterate. I use ‘second’ and ‘foreign’ spoke on the streets?’ (Greenwood, atque id dicitur non in compitis tantum interchangeably of a language, as any pp. 202–3). neque in plebe volgaria … (‘And that is said distinction that may be made is not ‘… the question of language use in not only at crossroads nor among the relevant in the context of a world in the case of social groups for whom a common people …’) (Gellius). which there were no nation-states (or language is not a second language, but who quod vulgo dicitur ossum, Latine os notions of political correctness). If I are regarded as secondary users of that dicitur (‘What is called ossum in the were to prefer one to the other it would language.’ (Greenwood, p.208). language of the common people, in be ‘foreign’: native speakers of Latin … quid tibi ego videor in epistulis? nonne Latin [i.e. ‘correct’ Latin] is called os’) regarded everyone else but Greek- plebeio sermone agere tecum?… epistulas (Augustine). -

Roman Vulgar Law in Late Antiquity

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg DETLEF LIEBS Roman Vulgar Law in Late Antiquity Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Boudewijn Sirks (Hrsg.): Aspects of law in late antiquity : dedicated to A.M. Honoré on the occasion of the sixtieth year of his teaching in Oxford. Oxford: Souls College, 2008, S. 35 - 53 Roman Vulgar Law in Late Antiquity* Detlef Liebs 1. Heinrich Brunner’s ‚Römisches Vulgarrecht’ The term ‚Römisches Vulgarrecht’, in English ‚Roman vulgar law’, was coined in 1880 by the historian of Germanic law Heinrich Brunner1 (1840-1915), professor at the renowned U- niversity of Berlin. He used the term in a definite sense: the law of the Romance peoples un- der Germanic rule, and he meant: in Italy under the Lombards and in Gaul under the Franks from the sixth century AD up to the twelfth. After the western Emperor had abdicated in 476 AD there was, in Gaul and in Italy under the Lombards, no responsible authority as a source of the Roman law which continued to be applied, so that the Romance peoples were left to their own to develop their actually Roman law then in force. The Germanic rulers in general did not especially concern for it, except on some sensitive points like punishing high treason, and the authority of the east Roman Emperor did not extend to the Lombard and Frankish kingdoms with their mainly romance population, except for some cultural aspects like or- thography. Thus the Franks accepted the Byzantine ph instead of f in terms like philosophy, whereas the Italian, Spanish and Portuguese languages persisted in f as ordered by the west roman Emperor Constans about 350 AD.2 Brunner evoked the parallel of the vulgar Latin language. -

Cicero's Style

MNS-245-albrecht.qxd 03/04/2003 12:13 Page i CICERO’S STYLE MNS-245-albrecht.qxd 03/04/2003 12:13 Page ii MNEMOSYNE BIBLIOTHECA CLASSICA BATAVA COLLEGERUNT H. PINKSTER • H. S. VERSNEL D.M. SCHENKEVELD • P. H. SCHRIJVERS S.R. SLINGS BIBLIOTHECAE FASCICULOS EDENDOS CURAVIT H. PINKSTER, KLASSIEK SEMINARIUM, OUDE TURFMARKT 129, AMSTERDAM SUPPLEMENTUM DUCENTESIMUM QUADRAGESIMUM QUINTUM MICHAEL VON ALBRECHT CICERO’S STYLE MNS-245-albrecht.qxd 03/04/2003 12:13 Page iii CICERO’S STYLE A SYNOPSIS FOLLOWED BY SELECTED ANALYTIC STUDIES BY MICHAEL VON ALBRECHT BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2003 MNS-245-albrecht.qxd 03/04/2003 12:13 Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Albrecht, Michael von. Cicero’s Style: a synopsis / by Michael von Albrecht. p. cm. – (Mnemosyne, bibliotheca classica Batava. Supplementum ; 245) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 90-04-12961-8 1. Cicero, Marcus Tullius–Literary style. 2. Speeches, addresses, etc., Latin–History and criticism. 3. Latin language–Style. 4. Rhetoric, Ancient. 5. Oratory, Ancient. I. Title. II. Series. PA6357.A54 2003 875’.01–dc21 2003045375 ISSN 0169-8958 ISBN 90 04 12961 8 © Copyright 2003 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Catullan Obscenity and Modern English Translation Tori Frances Lee Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-2016 Catullan Obscenity and Modern English Translation Tori Frances Lee Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Other Classics Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Tori Frances, "Catullan Obscenity and Modern English Translation" (2016). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 703. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/703 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Classics Catullan Obscenity and Modern English Translation by Tori Frances Lee A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2016 St. Louis, Missouri © 2016, Tori F. Lee Table of Contents Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………………..iii Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter 1: Os an culum? Obscenity and Circumlocution in Catullus…………………………...16 Chapter 2: Traduttore, traditore: English Adaptations of Catullan Profanity…………………...34 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….64 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..80 Appendix: Catullan obscenities and their English translations………………………..…………85 ii Acknowledgments This thesis is the product of a year of brainstorming, refining, and re-imagining what I originally thought would be a simple paper on Catullan reception. I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to Prof. -

Latin Graduate Award Information • an Extinct Language from Ancient

Latin Graduate Award Information An extinct language from Ancient Rome. Evidence suggests it was first used over 2500 years ago. Latin influenced many languages, especially French, Spanish and Italian – ‘The Romance Languages’. Latin is an extinct language that was the official language of Ancient Rome. It was also written, read and spoken across the Roman Empire. Artefacts inscribed with written Latin have been found from as far back as 500BC! There were two different types Latin: Classical Latin (used in writing for the educated Romans) and Vulgar Latin (used by the common townspeople in spoken conversations). Is Latin still used today? Latin is an extinct language. This means that it is no longer spoken by anyone as a first language. However, many people study it in school. It is still useful, because it shows how society worked in past times. It also helps people understand modern words in many languages today. Spanish, French and Italian (among others) are known as ‘The Romance Languages’ and they have many similarities to Latin and to each other. Latin is still used to name technical things such as species of living things, medicine and diseases. Therefore, lots of Latin is found in Science. Latin was very important to Christianity for many centuries. It is still spoken today during some religious places and churches. It is an official language in the Vatican, where the Pope leads the Roman Catholic Church. If people in the Vatican speak different first languages, they use Latin to communicate. Is Latin like English? The Romans invaded - and settled in - Britain in AD 43. -

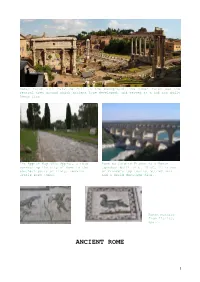

Ancient Rome Developed, and Served As a Hub for Daily Roman Life

Roman Forum with Palatine Hill in the background. The Roman Forum was the central area around which ancient Rome developed, and served as a hub for daily Roman life. The Appian Way (Via Appia), a road Pont du Gard in France is a Roman connecting the city of Rome to the aqueduct built in c. 19 BC. It is one southern parts of Italy, remains of France's top tourist attractions usable even today. and a World Heritage Site. Roman mosaics from Italica, Spain. ANCIENT ROME 1 At the height of the Roman Empire, Rome's influence reached as far north as Hadrian's Wall in present day England, as far south as Egypt, and as far east as present day Turkey and Syria. I) INTRODUCTION Ancient Rome was a civilization that started as a small agricultural community on the Italian Peninsula in the 9th century BC. In its twelve centuries of existence, Roman civilization came to dominate Western Europe and the area surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. Ancient Rome can be divided into three periods. Founded in 753 BC, it was first ruled by kings. Then, in 509 BC, a republic was established. The republic became an empire in 27 BC. That empire lasted for almost 500 years. But in the fourth century the Roman Empire was divided into two parts. Soon, the western part of the empire went into decline and its ruler was deposed by a barbarian leader in 476. The eastern part became the Byzantine Empire and lived on for another millennium. Because of the Roman Empire, Roman culture spread to Western Europe and the area surrounding the Mediterranean Sea.