John Owen Between Orthodoxy and Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD Christ Church was founded in 1546, and there had been a college here since 1525, but prior to the Dissolution of the monasteries, the site was occupied by a priory dedicated to the memory of St Frideswide, the patron saint of both university and city. St Frideswide, a noble Saxon lady, founded a nunnery for herself as head and for twelve more noble virgin ladies sometime towards the end of the seventh century. She was, however, pursued by Algar, prince of Leicester, for her hand in marriage. She refused his frequent approaches which became more and more desperate. Frideswide and her ladies, forewarned miraculously of yet another attempt by Algar, fled up river to hide. She stayed away some years, settling at Binsey, where she performed healing miracles. On returning to Oxford, Frideswide found that Algar was as persistent as ever, laying siege to the town in order to capture his bride. Frideswide called down blindness on Algar who eventually repented of his ways, and left Frideswide to her devotions. Frideswide died in about 737, and was canonised in 1480. Long before this, though, pilgrims came to her shrine in the priory church which was now populated by Augustinian canons. Nothing remains of Frideswide’s nunnery, and little - just a few stones - of the Saxon church but the cathedral and the buildings around the cloister are the oldest on the site. Her story is pictured in cartoon form by Burne-Jones in one of the windows in the cathedral. One of the gifts made to the priory was the meadow between Christ Church and the Thames and Cherwell rivers; Lady Montacute gave the land to maintain her chantry which lay in the Lady Chapel close to St Frideswide’s shrine. -

A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2009-05-01 A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L) Gary P. Gillum [email protected] Susan Wheelwright O'Connor Alexa Hysi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Gillum, Gary P.; O'Connor, Susan Wheelwright; and Hysi, Alexa, "A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L)" (2009). Faculty Publications. 12. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/12 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 833 FAIRFAX, JOHN, 1623-1700. Rare 922.542 St62f 1681 Presbýteros diples times axios, or, The true dignity of St. Paul's elder, exemplified in the life of that reverend, holy, zealous, and faithful servant, and minister of Jesus Christ Mr. Owne Stockton ... : with a collection of his observations, experiences and evidences recorded by his own hand : to which is added his funeral sermon / by John Fairfax. London : Printed by H.H. for Tho. Parkhurst at the Sign of the Bible and Three Crowns, at the lower end of Cheapside, 1681. Description: [12], 196, [20] p. ; 15 cm. References: Wing F 129. Subjects: Stockton, Owen, 1630-1680. Notes: Title enclosed within double line rule border. "Mors Triumphata; or The Saints Victory over Death; Opened in a Funeral Sermon ... " has special title page. 834 FAIRFAX, THOMAS FAIRFAX, Baron, 1612-1671. -

H Bavinck Preface Synopsis

University of Groningen Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae van den Belt, Hendrik; de Vries-van Uden, Mathilde Published in: The Bavinck review IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H., & de Vries-van Uden, M., (TRANS.) (2017). Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae. The Bavinck review, 8, 101-114. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 BAVINCK REVIEW 8 (2017): 101–114 Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae Henk van den Belt and Mathilde de Vries-van Uden* Introduction to Bavinck’s Preface On the 10th of June 1880, one day after his promotion on the ethics of Zwingli, Herman Bavinck wrote the following in his journal: “And so everything passes by and the whole period as a student lies behind me. -

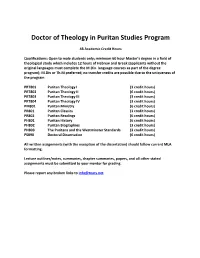

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program 48 Academic Credit Hours Qualifications: Open to male students only; minimum 60 hour Master’s degree in a field of theological study which includes 12 hours of Hebrew and Greek (applicants without the original languages must complete the M.Div. language courses as part of the degree program); M.Div or Th.M preferred; no transfer credits are possible due to the uniqueness of the program. PRT801 Puritan Theology I (3 credit hours) PRT802 Puritan Theology II (6 credit hours) PRT803 Puritan Theology III (3 credit hours) PRT804 Puritan Theology IV (3 credit hours) PM801 Puritan Ministry (6 credit hours) PR801 Puritan Classics (3 credit hours) PR802 Puritan Readings (6 credit hours) PH801 Puritan History (6 credit hours) PH802 Puritan Biographies (3 credit hours) PH803 The Puritans and the Westminster Standards (3 credit hours) PS890 Doctoral Dissertation (6 credit hours) All written assignments (with the exception of the dissertation) should follow current MLA formatting. Lecture outlines/notes, summaries, chapter summaries, papers, and all other stated assignments must be submitted to your mentor for grading. Please report any broken links to [email protected]. PRT801 PURITAN THEOLOGY I: (3 credit hours) Listen, outline, and take notes on the following lectures: Who were the Puritans? – Dr. Don Kistler [37min] Introduction to the Puritans – Stuart Olyott [59min] Introduction and Overview of the Puritans – Dr. Matthew McMahon [60min] English Puritan Theology: Puritan Identity – Dr. J.I. Packer [79] Lessons from the Puritans – Ian Murray [61min] What I have Learned from the Puritans – Mark Dever [75min] John Owen on God – Dr. -

The Percival J. Baldwin Puritan Collection

The Percival J. Baldwin Puritan Collection Accessing the Collection: 1. Anyone wishing to use this collection for research purposes should complete a “Request for Restricted Materials” form which is available at the Circulation desk in the Library. 2. The materials may not be taken from the Library. 3. Only pencils and paper may be used while consulting the collection. 4. Photocopying and tracing of the materials are not permitted. Classification Books are arranged by author, then title. There will usually be four elements in the call number: the name of the collection, a cutter number for the author, a cutter number for the title, and the date. Where there is no author, the cutter will be A0 to indicate this, to keep filing in order. Other irregularities are demonstrated in examples which follow. BldwnA <-- name of collection H683 <-- cutter for author O976 <-- cutter for title 1835 <-- date of publication Example. A book by the author Thomas Boston, 1677-1732, entitled, Human nature in its fourfold state, published in 1812. BldwnA B677 <-- cutter for author H852 <-- cutter for title 1812 <-- date of publication Variations in classification scheme for Baldwin Puritan collection Anonymous works: BldwnA A0 <---- Indicates no author G363 <---- Indicates title 1576 <---- Date Bibles: BldwnA B524 <---- Bible G363 <---- Geneva 1576 <---- Date Biographies: BldwnA H683 <---- cuttered on subject's name Z5 <---- Z5 indicates biography R633Li <---- cuttered on author's name, 1863 then first two letters of title Letters: BldwnA H683 <----- cuttered -

John Cotton's Middle Way

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 John Cotton's Middle Way Gary Albert Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Gary Albert, "John Cotton's Middle Way" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 251. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/251 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN COTTON'S MIDDLE WAY A THESIS presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by GARY A. ROWLAND August 2011 Copyright Gary A. Rowland 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Historians are divided concerning the ecclesiological thought of seventeenth-century minister John Cotton. Some argue that he supported a church structure based on suppression of lay rights in favor of the clergy, strengthening of synods above the authority of congregations, and increasingly narrow church membership requirements. By contrast, others arrive at virtually opposite conclusions. This thesis evaluates Cotton's correspondence and pamphlets through the lense of moderation to trace the evolution of Cotton's thought on these ecclesiological issues during his ministry in England and Massachusetts. Moderation is discussed in terms of compromise and the abatement of severity in the context of ecclesiastical toleration, the balance between lay and clerical power, and the extent of congregational and synodal authority. -

John Owen's Conceptions of Christian Unity and Schism Author

Title: All Subjects of the Kingdom of Christ: John Owen’s Conceptions of Christian Unity and Schism Author: Sungho Lee Date: 2007 Degree: Ph. D., Calvin Theological Seminary Supervisor: Richard A. Muller External Reader: Carl R. Trueman Digital full text: http://www.calvin.edu/library/database/dissertations/Lee_Sungho.pdf Call Number: BV4070 .C2842 2007 .L44 ABSTRACT Throughout the seventeenth century the Church of England experienced disintegration and schism. Each Protestant party charged the other with breaking the unity of the church. For this reason, schism and unity were one of the most controversial issues that leading theologians wrestled with. However, scholars have not paid due attention to this issue. The object of this dissertation is to explore how John Owen, a great leader of the second- generation Congregationalists, defended Congregationalism, Protestantism, and Nonconformity from the charge of schism. Aware that the ecclesiological terms, such as “schism,” “unity,” and “separation,” were seriously abused by his opponents, Owen carefully redefined those terms based upon his own biblical interpretation. Accordingly, the dissertation surveys Owen’s ecclesiastical life and works against the historical background of ecclesiology in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, recognizing that ecclesiology was one of Owen’s main theological concerns throughout his life, and that ecclesiology in general and schism and unity in particular were significantly developed by him in debate. The general tenets of Owen’s ecclesiology are examined in his two definitive ecclesiological works: An Inquiry into the Original, Nature, Institution, Power, Order, and Communion of Evangelical Churches and The True Nature of a Gospel Church. Examination of Owen’s Of Schism and his controversy with Daniel Cawdrey, a prominent English Presbyterian, shows more precisely what the real issues were between Congregationalists and Presbyterians with regard to the unity of the church. -

Curriculum Vitae—Greg Salazar

GREG A. SALAZAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORICAL THEOLOGY PURITAN REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY PHD CANDIDATE, THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE 2965 Leonard Street Phone: (616) 432-3419 Grand Rapids, MI 49525 Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL OBJECTIVE To train and form the next generation of Reformed Christian leaders through a career of teaching and publishing in the areas of church history, historical theology, and systematic theology. I also plan to serve the Presbyterian church as a teaching elder through a ministry of shepherding, teaching, and preaching. EDUCATION The University of Cambridge (Selwyn College) 2013-2017 (projected) PhD in History Dissertation: “Daniel Featley and Calvinist Conformity in Early Stuart England” Supervisor: Professor Alex Walsham Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando 2009-2012 Master of Divinity The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2003-2007 Bachelor of Arts (Religious Studies) DOCTORAL RESEARCH My doctoral research is on the historical, theological, and intellectual contexts of the Reformation in England—specifically analyzing the doctrinal, ecclesiological, and pietistic links between puritanism and the post-Reformation English Church in the lead-up to the Westminster Assembly, through the lens of the English clergyman and Westminster divine Daniel Featley (1582-1645). AREAS OF RESEARCH SPECIALIZATION Broadly speaking, my competency and interests are in church history, historical theology, systematic theology, spiritual formation, and Islam. Specific Research Interests include: Post-Reformation -

John Owen Concepts

John Owen 1616-1683 On Temptation and Sin: • Of the Mortification of Sin in Believers, 1656 • Of Temptation, 1658 • The Glory of Christ, 1684/1696 • Of The Dominion of Sin and Grace, 1688 • The Works of John Owen. 24 vols. Introduction 1. Puritan, English Nonconformist, Congregationalist pastor, theologian and administrator at Oxford. He’s considered by many to be the greatest English speaking theologian. A prolific writer. One of his greatest works is “The Death of Death in the Death of Christ,”* 1647, a defense of Calvinism’s particular redemption (limited atonement) VS Arminianism’s universal redemption. In 1644, he married Mary Rooke. The couple had 11 children, 10 died in infancy. One daughter survived to adulthood, married, and died shortly following. His wife died in 1675. He died in 1683 and is buried in Bunhill Fields. 2. Difficult to read. Thinks in Latin. Writes in English. Of Temptation (1658) is probably his most readable work. 3. Early Owen (1650’s) VS later Owen (1680’s)—Mortification (Sin) to Vivification (Glory) *Required Reading: Packer’s Introductory Essay to John Owen’s Death of Death in the Death of Christ. Download PDF: http://www.all-of-grace.org/pub/others/deathofdeath.html © 2017 Applied Theology Project, Steve Childers and John Frame, www.pathwaylearning.org 1 I. Taxonomy of the Human Soul = Trinity of Faculties 1. Mind/Understanding 2. Affections/Emotions 3. Will/Volition “The faculties move cross and contrary to one another; the will chooses not the good which the mind discovers. Commonly the affections get the sovereignty, and draw the whole soul captive after them” (VI:173). -

William Perkins (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 Pm 1602) Earned a Bachelor’S Plenary Session # 1 Degree in 1581 and a Mas- Dr

MaY 19 (FrIDaY eVeNING) William perkinS (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 pm 1602) earned a bachelor’s plenary Session # 1 degree in 1581 and a mas- Dr. Sinclair Ferguson, ter’s degree in 1584 from WILLIAM William Perkins—A Plain Preacher Christ’s College in Cam- bridge. During those stu- dent years he joined up PERKINS MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY MOrNING) with Laurence Chaderton, CONFereNCe 9:00 - 10:15 am who became his personal plenary Session # 2 tutor and lifelong friend. IN THE ROUND CHURCH Dr. Joel Beeke Perkins and Chaderton met William Perkins’s Largest Case of Conscience with Richard Greenham, Richard Rogers, and others in a spiritual brotherhood 10:30 – 11:45 am at Cambridge that espoused Puritan convictions. plenary Session # 3 Dr. Geoff Thomas From 1584 until his death, Perkins served as lectur- The Pursuit of Godliness in the er, or preacher, at Great St. Andrew’s Church, Cam- Ministry of William Perkins bridge, a most influential pulpit across the street from Christ’s College. He also served as a teaching fellow 12:00 – 6:45 pm at Christ’s College, catechized students at Corpus Free Time Christi College on Thursday afternoons, and worked as a spiritual counselor on Sunday afternoons. In MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY eVeNING) these roles Perkins influenced a generation of young 7:00 – 8:15 pm students, including Richard Sibbes, John Cotton, John plenary Session # 4 Preston, and William Ames. Thomas Goodwin wrote Dr. Stephen Yuille that when he entered Cambridge, six of his instruc- Contending for the Faith: Faith and Love in Perkins’s tors who had sat under Perkins were still passing on Defense of the Protestant Religion his teaching. -

Enlightenment and Dissent

Editors Martin Fitzpatrick, D.O.Thomas Advisory Editorial Board Carl B. Cone Unil•ersity of Kentuc/..:y James Dybikowski Unirersity of British Columbia Enlightenment lain McCalman Australian National Unirersity and Dissent John G. McEvoy The University of Cincinnati M. E. Ogborn formerely General Manager and Actuary, Equitable Life Assurance Society W. Bernard Peach Duke University Mark Philp Oriel College Oxford D. D. Raphael Imperial College of Science and Technology D. A. Rees Jesus College, O.Ajord T. A. Roberts The University College of Wales Robert E. Schofield fowa State University Alan P. F. Sell United Theological College, Aberystwyth John Stephens Director, Rohin Waterfield Ltd., O.Ajord R. K. Webb University of Maryland No.151996 ISSN 0262 7612 © 1997 Martin Fitzpatrick and D. 0. Thomas The University of Wales. Aberystwyth Enlightenment and Dissent No. 15 1996 Editorial It is an apparent paradox that Enlightenment studies are flourishing more than ever and yet are in a state of crisis. The proliferation of such studies has made. it ever more difficult to retain a sense of the particularity of the Enlightenment and a grasp of its synergy. The situation has been long in the making and is associated with the success of the International Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies and of the Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth-Century. Some time ago John Lough in an illuminating article made a plea for a return to an older 'history of thought' pattern of study. For all its attractions that would hardly solve the problem of defining Enlightenment and locating it within eighteenth-century culture and society. -

John Owen on Spiritual Gifts

John Owen on Spiritual Gifts by J. I. Packer The subject of spiritual gifts was not much debated in Puritan theology, and the only full-scale treatment of it by a major writer, so far as I know, is John Owen’s Discourse of Spiritual Gifts. This, the last instalment of Owen’s great analysis of biblical teaching on the Holy Spirit, seems to have been written in 1679 or 1680,1 though it was not printed till 1693, ten years after his death. Owen’s Discourse is fully characteristic both of himself and of the general Puritan view of its theme. It is desirable to delimit explicitly the area within which our study of Owen will move, for there could be false expectations here. To many Christians today, the phrase ‘spiritual gifts’ suggests a wider range of questions and concerns than it did to the Puritans. Throughout the century that separated William Perkins’ pioneer ventures in pastoral theology (The Arte of Prophecying, Latin 1592, English 1600; The Calling of the Ministerie, 1605) from Owen’s Discourse, Puritan attention when discussing gifts was dominated by their interest in the ordained ministry, and hence in those particular gifts which qualify a man for ministerial office, and questions about other gifts to other persons were rarely raised. Preoccupied as they were— and as their times required them to be—with securing high standards in the ministry, and educating layfolk out of superstition and fanaticism, the Puritans had both their minds and their hands full, and modern questions about laymen’s gifts and service were given less of an airing than we might have expected or hoped for.