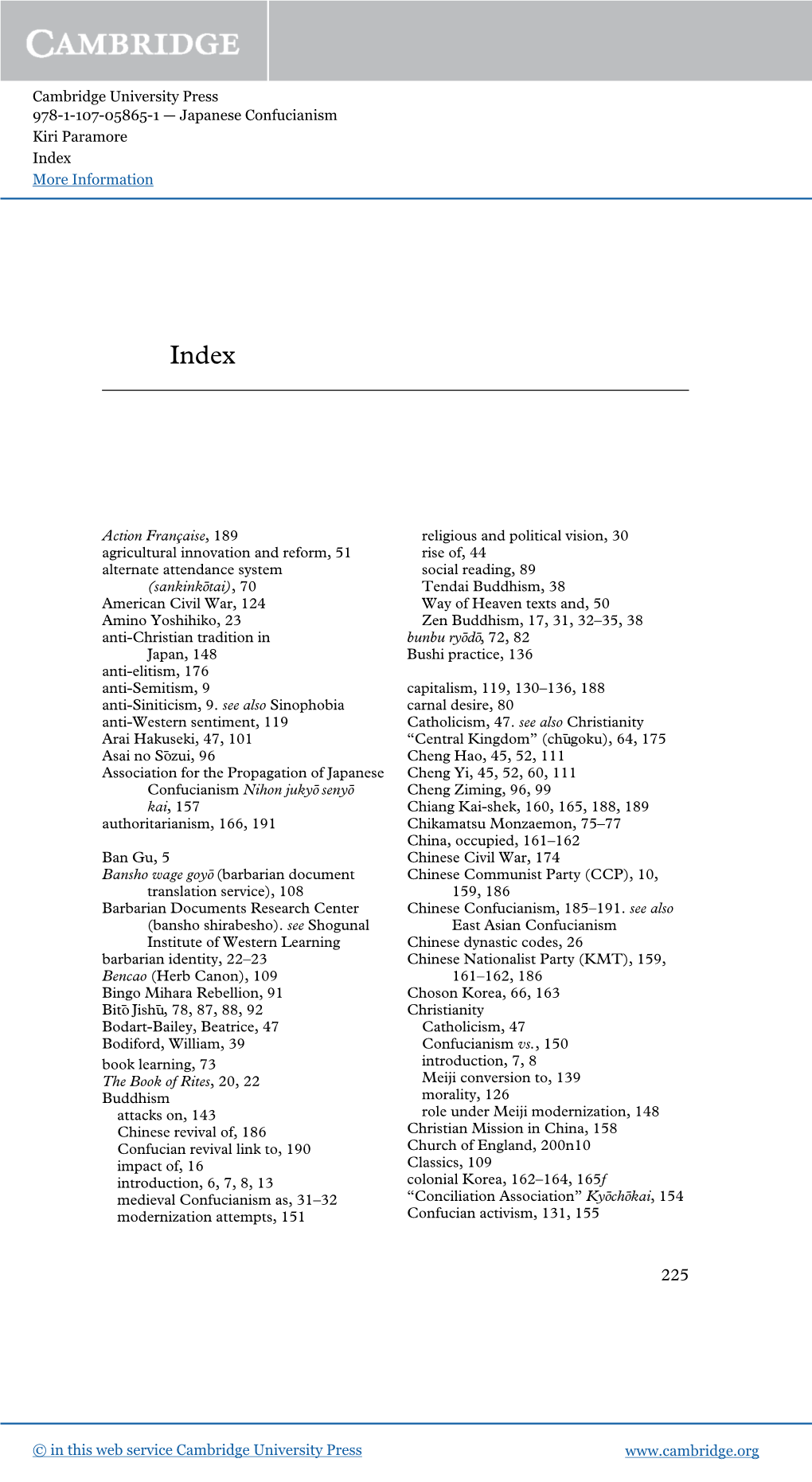

Japanese Confucianism Kiri Paramore Index More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses March 2015 The Unnatural World: Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho Eric Fischbach University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fischbach, Eric, "The Unnatural World: Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho" (2015). Masters Theses. 146. https://doi.org/10.7275/6499369 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/146 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNNATURAL WORLD: ANIMALS AND MORALITY TALES IN HAYASHI RAZAN’S KAIDAN ZENSHO A Thesis Presented by ERIC D. FISCHBACH Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2015 Asian Languages and Literatures - Japanese © Copyright by Eric D. Fischbach 2015 All Rights Reserved THE UNNATURAL WORLD: ANIMALS AND MORALITY TALES IN HAYASHI RAZAN’S KAIDAN ZENSHO A Thesis Presented by ERIC D. FISCHBACH Approved as to style and content by: __________________________________________ Amanda C. Seaman, Chair __________________________________________ Stephen Miller, Member ________________________________________ Stephen Miller, Program Head Asian Languages and Literatures ________________________________________ William Moebius, Department Head Languages, Literatures, and Cultures ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all my professors that helped me grow during my tenure as a graduate student here at UMass. -

Tetsugaku International Journal of the Philosophical Association of Japan

ISSN 2432-8995 Tetsugaku International Journal of the Philosophical Association of Japan Volume 2 2018 Special Theme Philosophy and Translation The Philosophical Association of Japan The Philosophical Association of Japan PRESIDENT KATO Yasushi (Hitotsubashi University) CHIEF OF THE EDITORIAL COMITTEE ICHINOSE Masaki (Musashino University) Tetsugaku International Journal of the Philosophical Association of Japan EDITORIAL BOARD CHIEF EDITOR NOTOMI Noburu (University of Tokyo) DEPUTY CHIEF EDITORS Jeremiah ALBERG (International Christian University) BABA Tomokazu (University of Nagano) SAITO Naoko (Kyoto University) BOARD MEMBERS DEGUCHI Yasuo (Kyoto University) FUJITA Hisashi (Kyushu Sangyo University) MURAKAMI Yasuhiko (Osaka University) SAKAKIBARA Tetsuya (University of Tokyo) UEHARA Mayuko (Kyoto University) ASSISTANT EDITOR TSUDA Shiori (Hitotsubashi University) SPECIAL THANKS TO Beverly Curran (International Christian University), Andrea English (University of Edingburgh), Enrico Fongaro (Tohoku University), Naomi Hodgson (Liverpool Hope University), Leah Kalmanson (Drake University), Sandra Laugier (Paris 1st University Sorbonne), Áine Mahon (University College Dublin), Mathias Obert (National University of Kaohsiung), Rossen Roussev (University of Veliko Tarnovo), Joris Vlieghe (University of Aberdeen), Yeong-Houn Yi (Korean University), Emma Williams (University of Warwick) Tetsugaku International Journal of the Philosophical Association of Japan Volume 2, Special Theme: Philosophy and Translation April 2018 Edited and published -

Study and Uses of the I Ching in Tokugawa Japan

Study Ching Tokugawa Uses of and I Japan the in Wai-ming Ng University Singapore National of • Ching $A (Book Changes) The of 1 particular significance has been book of a history. interest and in Asian East Divination philosophy basis its and derived from it on integral of Being civilization. Chinese within parts orbit the Chinese of the cultural were sphere, Japan traditional Ching development indebted for the the 1 of of its to aspects was culture. Japan The arrived in later sixth than the and little studied text in century no was (539-1186). Japan ancient readership expanded major It literate such Zen to groups as high-ranking monks, Buddhist courtiers, and period warriors medieval in the (1186- 1603). Ching scholarship 1 during reached Tokugawa its period the (1603-1868) apex Ching when the became 1 popular of the influential and Chinese This 2 most texts. one preliminary is provide work aims which brief Ching of overview 1 to essay a a scholarship highlighting Tokugawa Japan, in popularity themes: several of the the text, major writings, schools, the scholars, of/Ching and characteristics the and scholarship. 3 Popularity Ching The of the I popularity Ching Tokugawa of the The Japan in acknowledged I has been by a t• •" :i• •b Miyazaki Japanese number scholars. of Michio Tokugawa scholar of a thought, has remarked: "There by [Tokugawa] reached Confucians consensus was a pre-Tokugawa historical of the For overview Wai-ming in Japan, Ng, Ching "The 1 in text a see Japan," Quarterly Ancient (Summer Culture 1996), 26.2 Wai-ming 73-76; Asian and Ng pp. -

From Taoism to Einstein Ki

FROM TAOISM TO EINSTEIN KI (ãC)and RI (óù) in Chinese and Japanese Thought. A Survey Olof G. Lidin (/Special page/ To Arild, Bjørk, Elvira and Zelda) CONTENTS Acknowledgements and Thanks 1 Prologue 2-7 Contents I. Survey of the Neo-Confucian Orthodoxy INTRODUCTION 8-11 1. The Neo-Confucian Doctrine 11-13 2. Investigation of and Knowledge of ri 14-25 3. The Origin and Development of the ri Thought 25-33 4. The Original ki thought 33-45 5. How do ri and ki relate to each other? 45-50 5.1 Yi T’oe-gye and the Four versus the Seven 50-52 6. Confucius and Mencius 52-55 7. The Development of Neo- Confucian Thought in China 55-57 7. 1 The Five Great Masters 57-58 7. 2 Shao Yung 58-59 7. 3 Chang Tsai 59-63 7. 4 Chou Tun-i 63-67 7. 5 Ch’eng Hao and Ch’eng I 67-69 8. Chu Hsi 69-74 9. Wang Yang-ming 74-77 10. Heaven and the Way 77-82 11. Goodness or Benevolence (jen) 82-85 12. Human Nature and kokoro 85-90 13. Taoism and Buddhism 90-92 14. Learning and Quiet Sitting 92-96 15. Neo-Confucian Thought in Statecraft 96-99 16. Neo-Confucian Historical (ki) Realism 99-101 17. Later Chinese and Japanese ri-ki Thought 101-105 II. Survey of Confucian Intellectuals in Tokugawa Japan INTRODUCTION 105-111 1. Fujiwara Seika 111-114 2. Matsunaga Sekigo 114-115 3. Hayashi Razan 115-122 3.1 Fabian Fukan 122-124 4. -

Nothingness and Desire an East-West Philosophical Antiphony

jordan lectures 2011 Nothingness and Desire An East-West Philosophical Antiphony James W. Heisig Updated 1 October 2013 (with apologies from the proofreader & author) University of Hawai‘i Press honolulu Prologue The pursuit of certitude and wealth lies at the foundations of the growth of human societies. Societies that care little to know for certain what is true and what is not, or those that have little concern for increasing their hold- ings—material, monetary, intellectual, geographical, or political—are easily swallowed up by those that do. The accumulation of certitude and of wealth has given us civilization and its discontents. Those at one end of the spec- trum who doubt fundamental truths or who forsake the prevailing criteria of wealth in the name of other values are kept in check by the mere fact of being outnumbered and outpowered. The further away individuals are from that extreme and the greater the routine and normalcy of the accumulation, the higher they are ranked in the chain of civility. The number of those who try to find a compromise somewhere in between is in constant flux. In one sense, access to literacy, education, democracy, and private property are crucial to increasing the population of the self-reflective who aim at transforming those pursuits away from the intolerance and greed that always seem to accompany them into something more worthy of a human existence. In another sense, the institutionalization of the means to that end menaces the role of self-reflection. As organizations established to control normalcy grow in influence and expropriate the law to insure their own continuation, the pursuit of certitude and wealth is driven further and further away from the reach of individual conscience. -

Keichū, Motoori Norinaga, and Kokugaku in Early Modern Japan

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Jeweled Broom and the Dust of the World: Keichū, Motoori Norinaga, and Kokugaku in Early Modern Japan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Emi Joanne Foulk 2016 © Copyright by Emi Joanne Foulk 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Jeweled Broom and the Dust of the World: Keichū, Motoori Norinaga, and Kokugaku in Early Modern Japan by Emi Joanne Foulk Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Herman Ooms, Chair This dissertation seeks to reconsider the eighteenth-century kokugaku scholar Motoori Norinaga’s (1730-1801) conceptions of language, and in doing so also reformulate the manner in which we understand early modern kokugaku and its role in Japanese history. Previous studies have interpreted kokugaku as a linguistically constituted communitarian movement that paved the way for the makings of Japanese national identity. My analysis demonstrates, however, that Norinaga¾by far the most well-known kokugaku thinker¾was more interested in pulling a fundamental ontology out from language than tying a politics of identity into it: grammatical codes, prosodic rhythms, and sounds and their attendant sensations were taken not as tools for interpersonal communication but as themselves visible and/or audible threads in the fabric of the cosmos. Norinaga’s work was thus undergirded by a positive understanding ii of language as ontologically grounded within the cosmos, a framework he borrowed implicitly from the seventeenth-century Shingon monk Keichū (1640-1701) and esoteric Buddhist (mikkyō) theories of language. Through philological investigation into ancient texts, both Norinaga and Keichū believed, the profane dust that clouded (sacred, cosmic) truth could be swept away, as if by a jeweled broom. -

Is Confucianism Philosophy? the Answers of Inoue Tetsujirō and Nakae Chōmin

Is Confucianism philosophy ? The answers of Inoue Tetsujirō and Nakae Chōmin Eddy Dufourmont To cite this version: Eddy Dufourmont. Is Confucianism philosophy ? The answers of Inoue Tetsujirō and Nakae Chōmin . Nakajima Takahiro. Whither Japanese Philosophy 2? Reflections through Other Eyes, , University of Tokyo Center of Philosophy, 2010. hal-01522302 HAL Id: hal-01522302 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01522302 Submitted on 19 May 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 71 4 Is Confucianism philosophy ? The answers of Inoue Tetsujirō and Nakae Chōmin Eddy DUFOURMONT University of Bordeaux 3/ CEJ Inalco Introduction: a philosophical debate from beyond the grave Is Chinese thought a philosophy? This question has been discussed by scholars in the last years from a philosophical point of view,1 but it is possible also to adopt a historical point of view to answer the ques- tion, since Japanese thinkers faced the same problem during Meiji period (1868–1912), when the acquisition of European thought put in question the place of Chinese -

Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century 十八世紀在德川日本 "頌華者" 和 "貶華者" 的 問題 – 以中醫及漢方為主

East Asian Science, Technology and Society: an International Journal DOI 10.1007/s12280-008-9042-9 Sinophiles and Sinophobes in Tokugawa Japan: Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century 十八世紀在德川日本 "頌華者" 和 "貶華者" 的 問題 – 以中醫及漢方為主 Benjamin A. Elman Received: 12 May 2008 /Accepted: 12 May 2008 # National Science Council, Taiwan 2008 Abstract This article first reviews the political, economic, and cultural context within which Japanese during the Tokugawa era (1600–1866) mastered Kanbun 漢 文 as their elite lingua franca. Sino-Japanese cultural exchanges were based on prestigious classical Chinese texts imported from Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) China via the controlled Ningbo-Nagasaki trade and Kanbun texts sent in the other direction, from Japan back to China. The role of Japanese Kanbun teachers in presenting language textbooks for instruction and the larger Japanese adaptation of Chinese studies in the eighteenth century is then contextualized within a new, socio-cultural framework to understand the local, regional, and urban role of the Confucian teacher–scholar in a rapidly changing Tokugawa society. The concluding part of the article is based on new research using rare Kanbun medical materials in the Fujikawa Bunko 富士川文庫 at Kyoto University, which show how some increasingly iconoclastic Japanese scholar–physicians (known as the Goiha 古醫派) appropriated the late Ming and early Qing revival of interest in ancient This article is dedicated to Nathan Sivin for his contributions to the History of Science and Medicine in China. Unfortunately, I was unable to present it at the Johns Hopkins University sessions in July 2008 honoring Professor Sivin or include it in the forthcoming Asia Major festschrift in his honor. -

Women's Liberation in Meiji Japan: Ruptures in Cultural Conceptions Of

Women’s liberation in Meiji Japan: ruptures in cultural conceptions INTERCULTURAL RELATIONS ◦ RELACJE MIĘDZYKULTUROWE ◦ 2020 ◦ 2 (8) https://doi.org/10.12797/RM.02.2020.08.10 Marina Teresinha De Melo Do Nascimento1 WOMEN’S LIBERATION IN MEIJI JAPAN: RUPTURES IN CULTURAL CONCEPTIONS OF FEMALE EDUCATION, SOCIAL ROLES, AND POLITICAL RIGHTS Abstract In 1872, the Meiji government issued the Education Act aiming to provide basic public education for boys and girls. The clash between Confucian ideals of wom- en and the recently introduced Western literature on female liberation divid- ed opinions among scholars. Having been influenced by the writings of British thinkers such as John Stuart Mill or Herbert Spencer, Japanese male and female thinkers proceeded to enlist various arguments in favor of female schooling and equal rights. Despite their advocating the right of women to attend schools, as well as their general agreement regarding the favorable results that girls’ educa- tion could bring to the nation, it is possible to identify key differences among scholars concerning the content of girls’ education and the nature of women’s rights. This paper focuses on Kishida Toshiko, an important female figure in Meiji politics who not only fought for female education but also emerged at the fore- front of activism in her advocacy of women’s political rights and universal suf- frage, showing the clear influence of British suffragette Millicent Garret Fawcett. Keywords: Meiji Japan, feminism, women’s suffrage, equal rights, female educa- tion INTRODUCTION The role that women would play in the new nation under construction and how the status of women would differ from the norms of the past was 1 PhD Candidate; Tohoku University; [email protected]. -

The NAKPA COURIER a Quarterly E-Newsletter of the North American Korean Philosophy Association No

The NAKPA COURIER A Quarterly E-Newsletter of the North American Korean Philosophy Association No. 3, September, 2014 A Letter from the Desktop Editor Dear Friends and Colleagues, Greetings once again from Omaha, Nebraska, US! I hope this letter finds you and all your loved ones well. In this issue of the NAKPA newsletter, you are able to find the full program of the conference on “The Spirit of Korean Philosophy: Six Debates and Their Significance,” an international conference generously supported by the Academy of Korean Studies as well as NAKPA. In addition, the full program of the two sessions on Korean philosophy at the upcoming Eastern APA in Philadelphia can be found. Also, NAKPA is pleased to report that it is able to host a session on Korean philosophy at the Central APA (St. Louis) and also at the Pacific APA (Seattle). The former will be focused on the Korean Studies on the Book of Changes, and the latter on the Korean political philosophy. (For details, see the section below.) Recently I learned that the Korean philosophy in the pre-modern era was not an isolated phenomenon but an outcome of active interactions with her counterparts both in China and Japan directly and those in Europe indirectly. For example, it has now been firmly established that the early Chosŏn Neo-Confucianism had a significant impact on the development of Tokugawa Confucianism. Here I am not talking about T’oegye’s well-known influence (partly by way of the Korean captive in Japan, Kang Hang) on the Shushigaku in Japan represented by Fujiwara Seika and Hayashi Razan. -

Japanese Reinterpretations of Confucianism: Itō Jinsai and His Project1

DOI: 10.4312/as.2021.9.2.183-208 183 Japanese Reinterpretations of Confucianism: Itō Jinsai and His Project1 Marko OGRIZEK* Abstract This article aims to introduce the study of Itō Jinsai from the point of view of the value of his Confucian interpretations within the context of the project of Confucian ethics—in other words, trying to ascertain in what ways Jinsai’s project can help facilitate the study of Confucian ethics beyond the realm of intellectual history in the global context of the 21st century. It is imperative to allow Jinsai’s notions, as much as possible, to speak for themselves; but it is also of great importance to first place Jinsai within his own time and inside the intellectual space in which he formulated his ideas. A number of scholarly sources will be considered, with the intention of illuminating Jinsai’s work from a few different angles. Keywords: Itō Jinsai, Japanese Confucianism, traditional Japanese philosophy, ethics Japonske reinterpretacije konfucijanstva: Itō Jinsai in njegov projekt Izvleček Članek je uvod v študij Itōja Jinsaija z vidika vrednosti njegovih konfucijanskih inter- pretacij v kontekstu projekta konfucijanske etike – z drugimi besedami, ugotoviti poskuša, kako lahko Jinsaijev projekt pripomore k študiju konfucijanske etike onkraj intelektualne zgodovine, v globalnem kontekstu 21. stoletja. Jinsaijevim pojmom moramo nujno do- voliti, da spregovorijo sami zase; vendar pa je zelo pomembno, da Jinsaija najprej umes- timo v njegov čas in intelektualni prostor, v katerem je osnoval svoje ideje. Upoštevani so različni akademski viri, s katerimi avtor Jinsaijevo delo osvetli z več različnih zornih kotov. Ključne besede: Itō Jinsai, japonski konfucianizem, tradicionalna japonska filozofija, etika 1 The author acknowledges the support of the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) in the framework of the research core funding Asian Languages and Cultures (P6-0243). -

An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Japanese Articles on Tokugawa Neo-Confucianism (Part One)

From Abe Yoshio to Maruyama Masao: An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Japanese Articles on Tokugawa Neo-Confucianism (Part One) John Allen Tucker University of North Florida Abe Ryiiichi p~ %F 1t-. "Yamaga Soko no shisho ron" &!t Itt ~_ ~ l' o 1! ;t~ (Yamaga Soko on [sino-Japanese] Historiography). Nihon rekishi a;$Ji~ ,284 (1972): 41-52. Abe discusses Yamaga Soko's (1622-85) emphasis on practical learning in historiography. Abe states that Soko esteemed Sima Qian's 6] .tI ~ (ca. 145-ca. 90 B.C.E.) remark, in his "Pre face" to the Shij i e. te.. (Records of the Grand Historian), assigning greater value to accounts of reality and practical matters than to those filled with empty words. In histori ography, Soko too preferred practicality rather than vacuous theorizing. Abe thus sees Soko as an "epoch-making figure" and "a pioneer" of realistic historical literature in Japan. Most of Soko's ideas on history are found in ch, 35, "Extending Learning" (J., chichi ljL~u.; Ch., zhizhi), of the · Yamaga gorui ~Jl !t~ (Classified Conversations of Yamaga Soko). Abe re veals that Soko's ideas launch from the Ming Neo-Confucian work the Xingli dachuan "'!':;:'f.~f. (Anthology of the School of Human Nature and Principle), ch, 55, ';studying History" (Shixue t. \ ~ ), which includes most of the passages sexs discusses. ___. "Kimon gakuha shokei no ryakuden to gakufii" ~ p~ ~~ ~~i:G) ~.l1~ k~~(Short Biographies of the Disciples of [Yamazaki Ansai's] Kimon Teachings and Their Academic Lineages). Yamazaki Ansai gakuha Ll1 aJJ~ '~~ j. ~ ~ (Yamazaki Ansai's School).