A Translation-Study of the Kana Shôri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perception of the Mediterranean World in China and Japan and Vice Versa in the History of Geography and Cartography

Perception of the Mediterranean World in China and Japan and vice versa in the History of Geography and Cartography Keiichi TAKEUCHI The purport of this paper, with its somewhat odd title, is firstly, to indicate the fact that it was the people of the Mediterranean world who first brought geographical and cartographical information pertaining to China and Japan to the Western world, and secondly that it was the people of the Mediterranean world who first brought geographical and cartographical information on Europe to China and Japan. We treat China and Japan together because, from the viewpoint of cultural history, Japan belongs to the sphere of Chinese culture or the world where Chinese ideograms have been commonly used; in fact, historically, Japan is indebted to China not only for its ideography, but also for a great deal of its cultural heritage. Regarding material culture, already in the ancient period, or even going as far back as prehistoric times, goods from China arrived in the Mediterranean world and goods from the Mediterranean world reached China and as far as Japan. Evidence of these early trading exchanges are to be found in present-day Japan in the shape of objects stored in the Shosoin, the seventh-century imperial treasure house in Nara. But the trading activities of the period in question were carried out by intermediary merchants; generally speaking, the producers of the goods traded were indifferent as to where the goods were ultimately sold, and the consumers of the goods were equally indifferent as to where the goods originated from. Therefore, the arrival of goods at any one place did not mean that intercourse involving an exchange of geographical information ensued. -

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

SUPPORTING the CHINESE, JAPANESE, and KOREAN LANGUAGES in the OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM by Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT the Asian L

SUPPORTING THE CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND KOREAN LANGUAGES IN THE OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM By Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT The Asian language versions of the OpenVMS operating system allow Asian-speaking users to interact with the OpenVMS system in their native languages and provide a platform for developing Asian applications. Since the OpenVMS variants must be able to handle multibyte character sets, the requirements for the internal representation, input, and output differ considerably from those for the standard English version. A review of the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean writing systems and character set standards provides the context for a discussion of the features of the Asian OpenVMS variants. The localization approach adopted in developing these Asian variants was shaped by business and engineering constraints; issues related to this approach are presented. INTRODUCTION The OpenVMS operating system was designed in an era when English was the only language supported in computer systems. The Digital Command Language (DCL) commands and utilities, system help and message texts, run-time libraries and system services, and names of system objects such as file names and user names all assume English text encoded in the 7-bit American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) character set. As Digital's business began to expand into markets where common end users are non-English speaking, the requirement for the OpenVMS system to support languages other than English became inevitable. In contrast to the migration to support single-byte, 8-bit European characters, OpenVMS localization efforts to support the Asian languages, namely Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, must deal with a more complex issue, i.e., the handling of multibyte character sets. -

Problematika České Transkripce Japonštiny a Pravidla Jejího Užívání Nihongo 日本語 社会 Šakai Fudži 富士 Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová Momidži Tókjó もみ じ 東京 Čotto ち ょっ と

チェ コ語 翼 čekogo cubasa šin’jó 信用 Problematika české transkripce japonštiny a pravidla jejího užívání nihongo 日本語 社会 šakai Fudži 富士 Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová momidži Tókjó もみ じ 東京 čotto ち ょっ と PROBLEMATIKA ČESKÉ TRANSKRIPCE JAPONŠTINY A PRAVIDLA JEJÍHO UŽÍVÁNÍ Ivona Barešová Monika Dytrtová Spolupracovala: Bc. Mária Ševčíková Oponenti: prof. Zdeňka Švarcová, Dr. Mgr. Jiří Matela, M.A. Tento výzkum byl umožněn díky účelové podpoře na specifi cký vysokoškolský výzkum udělené roku 2013 Univerzitě Palackého v Olomouci Ministerstvem školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy ČR (FF_2013_044). Neoprávněné užití tohoto díla je porušením autorských práv a může zakládat občanskoprávní, správněprávní, popř. trestněprávní odpovědnost. 1. vydání © Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová, 2014 © Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, 2014 ISBN 978-80-244-4017-0 Ediční poznámka V publikaci je pro přepis japonských slov užito české transkripce, s výjimkou jejich výskytu v anglic kém textu, kde se objevuje původní transkripce anglická. Japonská jména jsou uváděna v pořadí jméno – příjmení, s výjimkou jejich uvedení v bibliogra- fi ckých citacích, kde se jejich pořadí řídí citační normou. Pokud není uvedeno jinak, autorkami překladů citací a parafrází jsou autorky této práce. V textu jsou použity následující grafi cké prostředky. Fonologický zápis je uveden standardně v šikmých závorkách // a fonetický v hranatých []. Fonetické symboly dle IPA jsou použity v rámci kapi toly 5. V případě, že není nutné zaznamenávat jemné zvukové nuance dané hlásky nebo že není kladen důraz na zvukové rozdíly mezi jed- notlivými hláskami, je jinde v textu, kde je to možné, z důvodu usnadnění porozumění užito namísto těchto specifi ckých fonetických symbolů písmen české abecedy, např. -

Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses March 2015 The Unnatural World: Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho Eric Fischbach University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fischbach, Eric, "The Unnatural World: Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho" (2015). Masters Theses. 146. https://doi.org/10.7275/6499369 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/146 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNNATURAL WORLD: ANIMALS AND MORALITY TALES IN HAYASHI RAZAN’S KAIDAN ZENSHO A Thesis Presented by ERIC D. FISCHBACH Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2015 Asian Languages and Literatures - Japanese © Copyright by Eric D. Fischbach 2015 All Rights Reserved THE UNNATURAL WORLD: ANIMALS AND MORALITY TALES IN HAYASHI RAZAN’S KAIDAN ZENSHO A Thesis Presented by ERIC D. FISCHBACH Approved as to style and content by: __________________________________________ Amanda C. Seaman, Chair __________________________________________ Stephen Miller, Member ________________________________________ Stephen Miller, Program Head Asian Languages and Literatures ________________________________________ William Moebius, Department Head Languages, Literatures, and Cultures ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all my professors that helped me grow during my tenure as a graduate student here at UMass. -

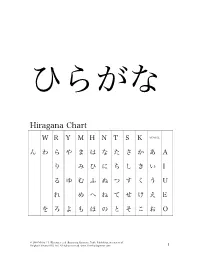

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II Class duration: 10 weeks, January 28–April 7, 2020 (no class March 24) Class meetings: Tuesdays at 5:30pm–7:30pm in Hellems 145 Instructor: Megan Husby, [email protected] Class session Resources before coming to Practice exercises after Communicative goals Grammar Vocabulary & topic class class Talking about things that you Verb Conjugation: Past tense Review of Hiragana Intro and あ column Fun Hiragana app for did in the past of long (polite) forms Japanese your Phone (~desu and ~masu verbs) Writing Hiragana か column Talking about your winter System: Hiragana song break Hiragana Hiragana さ column (Recognition) Hiragana Practice クリスマス・ハヌカー・お Hiragana た column Worksheet しょうがつ 正月はなにをしましたか。 Winter Sports どこにいきましたか。 Hiragana な column Grammar Review なにをたべましたか。 New Year’s (Listening) プレゼントをかいましたか/ Vocab Hiragana は column もらいましたか。 Genki I pg. 110 スポーツをしましたか。 Hiragana ま column だれにあいましたか。 Practice Quiz Week 1, えいがをみましたか。 Hiragana や column Jan. 28 ほんをよみましたか。 Omake (bonus): Kasajizō: うたをききましたか/ Hiragana ら column A Folk Tale うたいましたか。 Hiragana わ column Particle と Genki: An Integrated Course in Japanese New Year (Greetings, Elementary Japanese pgs. 24-31 Activities, Foods, Zodiac) (“Japanese Writing System”) Particle と Past Tense of desu (Affirmative) Past Tense of desu (Negative) Past Tense of Verbs Discussing family, pets, objects, Verbs for being (aru and iru) Review of Katakana Intro and ア column Katakana Practice possessions, etc. Japanese Worksheet Counters for people, animals, Writing Katakana カ column etc. System: Genki I pgs. 107-108 Katakana Katakana サ column (Recognition) Practice Quiz Katakana タ column Counters Katakana ナ column Furniture and common Katakana ハ column household items Katakana マ column Katakana ヤ column Katakana ラ column Week 2, Feb. -

The Degree of the Speaker's Negative Attitude in a Goal-Shifting

In Christopher Brown and Qianping Gu and Cornelia Loos and Jason Mielens and Grace Neveu (eds.), Proceedings of the 15th Texas Linguistics Society Conference, 150-169. 2015. The degree of the speaker’s negative attitude in a goal-shifting comparison Osamu Sawada∗ Mie University [email protected] Abstract The Japanese comparative expression sore-yori ‘than it’ can be used for shifting the goal of a conversation. What is interesting about goal-shifting via sore-yori is that, un- like ordinary goal-shifting with expressions like tokorode ‘by the way,’ using sore-yori often signals the speaker’s negative attitude toward the addressee. In this paper, I will investigate the meaning and use of goal-shifting comparison and consider the mecha- nism by which the speaker’s emotion is expressed. I will claim that the meaning of the pragmatic sore-yori conventionally implicates that the at-issue utterance is preferable to the previous utterance (cf. metalinguistic comparison (e.g. (Giannakidou & Yoon 2011))) and that the meaning of goal-shifting is derived if the goal associated with the at-issue utterance is considered irrelevant to the goal associated with the previous utterance. Moreover, I will argue that the speaker’s negative attitude is shown by the competition between the speaker’s goal and the hearer’s goal, and a strong negativity emerges if the goals are assumed to be not shared. I will also compare sore-yori to sonna koto-yori ‘than such a thing’ and show that sonna koto-yori directly expresses a strong negative attitude toward the previous utterance. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Legacy Character Sets & Encodings

Legacy & Not-So-Legacy Character Sets & Encodings Ken Lunde CJKV Type Development Adobe Systems Incorporated bc ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/cjkv/unicode/iuc15-tb1-slides.pdf Tutorial Overview dc • What is a character set? What is an encoding? • How are character sets and encodings different? • Legacy character sets. • Non-legacy character sets. • Legacy encodings. • How does Unicode fit it? • Code conversion issues. • Disclaimer: The focus of this tutorial is primarily on Asian (CJKV) issues, which tend to be complex from a character set and encoding standpoint. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations dc • GB (China) — Stands for “Guo Biao” (国标 guóbiâo ). — Short for “Guojia Biaozhun” (国家标准 guójiâ biâozhün). — Means “National Standard.” • GB/T (China) — “T” stands for “Tui” (推 tuî ). — Short for “Tuijian” (推荐 tuîjiàn ). — “T” means “Recommended.” • CNS (Taiwan) — 中國國家標準 ( zhôngguó guójiâ biâozhün) in Chinese. — Abbreviation for “Chinese National Standard.” 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • GCCS (Hong Kong) — Abbreviation for “Government Chinese Character Set.” • JIS (Japan) — 日本工業規格 ( nihon kôgyô kikaku) in Japanese. — Abbreviation for “Japanese Industrial Standard.” — 〄 • KS (Korea) — 한국 공업 규격 (韓國工業規格 hangug gongeob gyugyeog) in Korean. — Abbreviation for “Korean Standard.” — ㉿ — Designation change from “C” to “X” on August 20, 1997. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • TCVN (Vietnam) — Tiu Chun Vit Nam in Vietnamese. — Means “Vietnamese Standard.” • CJKV — Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated What Is A Character Set? dc • A collection of characters that are intended to be used together to create meaningful text. -

Tetsugaku International Journal of the Philosophical Association of Japan

ISSN 2432-8995 Tetsugaku International Journal of the Philosophical Association of Japan Volume 2 2018 Special Theme Philosophy and Translation The Philosophical Association of Japan The Philosophical Association of Japan PRESIDENT KATO Yasushi (Hitotsubashi University) CHIEF OF THE EDITORIAL COMITTEE ICHINOSE Masaki (Musashino University) Tetsugaku International Journal of the Philosophical Association of Japan EDITORIAL BOARD CHIEF EDITOR NOTOMI Noburu (University of Tokyo) DEPUTY CHIEF EDITORS Jeremiah ALBERG (International Christian University) BABA Tomokazu (University of Nagano) SAITO Naoko (Kyoto University) BOARD MEMBERS DEGUCHI Yasuo (Kyoto University) FUJITA Hisashi (Kyushu Sangyo University) MURAKAMI Yasuhiko (Osaka University) SAKAKIBARA Tetsuya (University of Tokyo) UEHARA Mayuko (Kyoto University) ASSISTANT EDITOR TSUDA Shiori (Hitotsubashi University) SPECIAL THANKS TO Beverly Curran (International Christian University), Andrea English (University of Edingburgh), Enrico Fongaro (Tohoku University), Naomi Hodgson (Liverpool Hope University), Leah Kalmanson (Drake University), Sandra Laugier (Paris 1st University Sorbonne), Áine Mahon (University College Dublin), Mathias Obert (National University of Kaohsiung), Rossen Roussev (University of Veliko Tarnovo), Joris Vlieghe (University of Aberdeen), Yeong-Houn Yi (Korean University), Emma Williams (University of Warwick) Tetsugaku International Journal of the Philosophical Association of Japan Volume 2, Special Theme: Philosophy and Translation April 2018 Edited and published