The Degree of the Speaker's Negative Attitude in a Goal-Shifting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

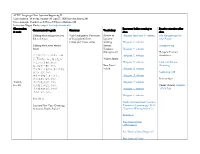

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II Class duration: 10 weeks, January 28–April 7, 2020 (no class March 24) Class meetings: Tuesdays at 5:30pm–7:30pm in Hellems 145 Instructor: Megan Husby, [email protected] Class session Resources before coming to Practice exercises after Communicative goals Grammar Vocabulary & topic class class Talking about things that you Verb Conjugation: Past tense Review of Hiragana Intro and あ column Fun Hiragana app for did in the past of long (polite) forms Japanese your Phone (~desu and ~masu verbs) Writing Hiragana か column Talking about your winter System: Hiragana song break Hiragana Hiragana さ column (Recognition) Hiragana Practice クリスマス・ハヌカー・お Hiragana た column Worksheet しょうがつ 正月はなにをしましたか。 Winter Sports どこにいきましたか。 Hiragana な column Grammar Review なにをたべましたか。 New Year’s (Listening) プレゼントをかいましたか/ Vocab Hiragana は column もらいましたか。 Genki I pg. 110 スポーツをしましたか。 Hiragana ま column だれにあいましたか。 Practice Quiz Week 1, えいがをみましたか。 Hiragana や column Jan. 28 ほんをよみましたか。 Omake (bonus): Kasajizō: うたをききましたか/ Hiragana ら column A Folk Tale うたいましたか。 Hiragana わ column Particle と Genki: An Integrated Course in Japanese New Year (Greetings, Elementary Japanese pgs. 24-31 Activities, Foods, Zodiac) (“Japanese Writing System”) Particle と Past Tense of desu (Affirmative) Past Tense of desu (Negative) Past Tense of Verbs Discussing family, pets, objects, Verbs for being (aru and iru) Review of Katakana Intro and ア column Katakana Practice possessions, etc. Japanese Worksheet Counters for people, animals, Writing Katakana カ column etc. System: Genki I pgs. 107-108 Katakana Katakana サ column (Recognition) Practice Quiz Katakana タ column Counters Katakana ナ column Furniture and common Katakana ハ column household items Katakana マ column Katakana ヤ column Katakana ラ column Week 2, Feb. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

A Study of Borrowing in Contemporary Spoken Japanese

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 1996 Integration of the American English lexicon: A study of borrowing in contemporary spoken Japanese Bradford Michael Frischkorn Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the First and Second Language Acquisition Commons Recommended Citation Frischkorn, Bradford Michael, "Integration of the American English lexicon: A study of borrowing in contemporary spoken Japanese" (1996). Theses Digitization Project. 1107. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/1107 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTEGRATION OF THE AMERICAN ENGLISH LEXICON: A STUDY OF BORROWING IN CONTEMPORARY SPOKEN JAPANESE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfilliiient of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Bradford Michael Frischkorn March 1996 INTEGRATION OF THE AMERICAN ENGLISH LEXICON: A STUDY OF BORROWING IN CONTEMPORARY SPOKEN JAPANESE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University,,, San Bernardino , by Y Bradford Michael Frischkorn ' March 1996 Approved by: Dr. Wendy Smith, Chair, English " Date Dr. Rong Chen ~ Dr. Sunny Hyonf ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis was to determine some of the behavioral characteristics of English loanwords in Japanese (ELJ) as they are used by native speakers in news telecasts. Specifically, I sought to examine ELJ from four perspectives: 1) part of speech, 2) morphology, 3) semantics, and 4) usage domain. -

A Performer's Guide to Minoru Miki's Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988)

University of Cincinnati Date: 4/22/2011 I, Margaret T Ozaki-Graves , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Voice. It is entitled: A Performer’s Guide to Minoru Miki’s _Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano_ (1988) Student's name: Margaret T Ozaki-Graves This work and its defense approved by: Committee chair: Jeongwon Joe, PhD Committee member: William McGraw, MM Committee member: Barbara Paver, MM 1581 Last Printed:4/29/2011 Document Of Defense Form A Performer’s Guide to Minoru Miki’s Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988) A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by Margaret Ozaki-Graves B.M., Lawrence University, 2003 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2007 April 22, 2011 Committee Chair: Jeongwon Joe, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Japanese composer Minoru Miki (b. 1930) uses his music as a vehicle to promote cross- cultural awareness and world peace, while displaying a self-proclaimed preoccupation with ethnic mixture, which he calls konketsu. This document intends to be a performance guide to Miki’s Sohmon III: for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988). The first chapter provides an introduction to the composer and his work. It also introduces methods of intercultural and artistic borrowing in the Japanese arts, and it defines the four basic principles of Japanese aesthetics. The second chapter focuses on the interpretation and pronunciation of Sohmon III’s song text. -

Section 18.1, Han

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

Japanisch 0. Planung

LMU München IATS Strukturkurs SS 2008 Robert Schikowski: Japanisch Japanisch Strukturkurs SS 2008 0. Planung 0.1 Aufbau des Kurses • Dieser Kurs ist ein Japanisch-Kurs für Linguisten. • Es ist ein Strukturkurs, d.h. es geht nicht darum, Japanisch sprechen zu lernen, sondern die Sprache von der wissenschaftlichen Seite zu betrachten. • Da davon auszugehen ist, dass die Level der Teilnehmer in Bezug auf linguistisches Wissen und Wissen über das Japanische sich unterscheiden, werde ich versuchen, einen Mittelweg zwischen zu einfach und zu schwer einzuschlagen; falls sich dennoch jemand notorisch über- oder unterfordert fühlt - bitte Bescheid sagen! • Bitte auch sonst Bescheid sagen, falls irgend etwas nicht passt. • Sehr wichtig: In diesem Kurs kann kein Schein erworben werden. 0.2 Semesterplan Sitzung Thema Seiten 15.04. Einführung: Japan & Japanisch 1 - 8 22.04. Schrift I (synchron) 9 - 18 29.04. Schrift II (diachron), Phonologie I (Phoneme) 19 - 25 06.05. Phonologie II (Allophonie, Transkription) 25 - 31 13.05. Phonologie III (More, Silbe, Ton) 31 - 39 20.05. Globale morphosyntaktische Struktur 40 - 46 27.05. Morphologie I (Verb) 47 - 56 03.06. Morphologie II (Nomen, Höflichkeit) 57 - 67 10.06. Syntax I (Valenz, Kasus) 68 - 80 17.06. Syntax II (Informationsstruktur, Passiv) 80 - 88 24.06. Syntax III (Valenzmanipulation) 88 - 93 01.07. Syntax IV (Konstruktionen, Sequentialisierung, Konjunktionen) 93 - 100 08.07. Syntax V (indirekte Rede, Relativsatz) 101 - 111 15.07. Puffer/Ausklang --- Aufgrund der Beschränkung auf ein Semester kommen in diesem Kurs notwendig viele Fragen zu kurz. Weiter gehende Fragen jedweder Art können aber jederzeit gerne an [email protected] gesendet werden. -

The Japanese Numeral Classifiers Hiki and Hatsu

Prototypes and Metaphorical Extensions: The Japanese Numeral Classifiers hiki and hatsu Hiroko Komatsu A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2018 Department of Japanese Studies School of Languages and Cultures Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Name: Hiroko Komatsu Signature: ……………………….. Date: ……..31 January 2018……. Abstract This study concerns the meaning of Japanese numeral classifiers (NCs) and, particularly, the elements which guide us to understand the metaphorical meanings they can convey. In the typological literature, as well as in studies of Japanese, the focus is almost entirely on NCs that refer to entities. NCs are generally characterised as being matched with a noun primarily based on semantic criteria such as the animacy, the physical characteristics, or the function of the referent concerned. However, in some languages, including Japanese, nouns allow a number of alternative NCs, so that it is considered that NCs are not automatically matched with a noun but rather with the referent that the noun refers to in the particular context in which it occurs. This study examines data from the Balanced Corpus of Contemporary Written Japanese, and focuses on two NCs as case studies: hiki, an entity NC, typically used to classify small, animate beings, and hatsu, an NC that is used to classify both entities and events that are typically explosive in nature. -

Iso/Iec Jtc 1/Sc 2/Wg 2 N2092 Date: 1999-09-13

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N2092 DATE: 1999-09-13 ISO/IEC JTC 1/ SC 2 /WG2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) -ISO/IEC 10646 Secretariat: ANSI Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Addition of forty eight characters Sources: Japanese National Body Project: -- Status: Proposal Action ID: For Consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 in Copenhagen Meeting Due Date: 1999-09-13 Distribution: P, O and L Members of ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 WG Conveners, Secretariats ISO/IEC JTC 1 Secretariat ISO/IEC ITTF No. of Pages: 25 Access Level: Open Web Issue #: Mile Ksar Convener -ISO/IEC/JTC1/SC2/WG2 Hewlett-Packard Company Phone: +1 650 857 8817 1501 Page Mill Rd., M/S 5U - L Fax(PC): +1 650 852 8500 Palo Alto, CA 94304 Alt. Fax: +1 650 857 4882 U. S. A. e-mail: [email protected] ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N2092 1999-09-13 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Addition of forty eight characters Source: JCS Committee, Japanese Standards Association (JSA) Status: JCS proposal Date: 1999-09-13 This document proposes forty eight characters used in Japan, and discusses the rationale for their inclusion. A new Japanese Industrial Standard, JIS X0213 is being developed in Japan, and it will be published by the end of this year. The new standard will include all characters in this proposal, so the adoption of them is very important in the view to keep upward compatibility with the Japanese products. Twenty extended KATAKANAs are used to describe the Language of AINU, Japanese aborigine. -

Hasegawasoliloquych2.Pdf

ne yo Sentence-final particles ne yo ne Yo ne yo ne yo ne yo ne yo ne ne yo ne yo Yoku furu ne/yo. Ne yo ne ne yo yo yo ne ne yo yo ne yo Sonna koto wa atarimae da ne/yo. Kimi no imooto-san, uta ga umai ne. ne Kushiro wa samui yo. Kyoo wa kinyoobi desu ne. ne ne Ne Ee, soo desu. Ii tenki da nee. Kyoo wa kinyoobi desu ne. ne Soo desu ne. Yatto isshuukan owarimashita ne. ne ne yo Juubun ja nai desu ka. Watashi to shite wa, mitomeraremasen ne. Chotto yuubinkyoku e itte kimasu ne. Ee, boku wa rikugun no shichootai, ima no yusoobutai da. Ashita wa hareru deshoo nee. shichootai yusoobutai Koshiji-san wa meshiagaru no mo osuki ne. ne affective common ground ne Daisuki. Oshokuji no toki ni mama shikaritaku nai kedo nee. Hitoshi no sono tabekata ni wa moo Denwa desu kedo/yo. ne yo yone Ashita irasshaimasu ka/ne. yo yone ne yo the coordination of dialogue ne Yo ne A soonan desu ka. Soo yo. Ikebe-san wa rikugun nandesu yone. ne yo ne yo ne yo ne Ja, kono zasshi o yonde-miyoo. Yo Kore itsu no zasshi daroo. A, nihon no anime da. procedural encoding anime ne yo A, kono Tooshiba no soojiki shitteru. Hanasu koto ga nakunatchatta. A, jisho wa okutta. Kono hon zuibun furui. Kyoo wa suupaa ni ikanakute ii. ka Kore mo tabemono. wa Dansu kurabu ja nakute shiataa. wa↓ wa wa↑ na Shikakui kuruma-tte suki janai. -

Enclosed CJK Letters and Months Range: 3200–32FF

Enclosed CJK Letters and Months Range: 3200–32FF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

IEEE 802.1 Interim Meeting Hiroshima, Japan January 2019

IEEE 802.1 Interim Meeting Hiroshima, Japan January 2019 1 Event Meeting dates January 14, 2019-January 18, 2019 Venue and location Hiroshima Oriental Hotel in Hiroshima 6-10, Tanakamachi, Naka-ku, Hiroshima, Japan 730-0026 http://oriental-hiroshima-jp.book.direct/en-gb Booked rooms are available on September 19, 2018(JST). https://asp.hotel-story.ne.jp/ver3d/plan.asp?p=A2ONG&c1=64101&c2=001 Please note: Check in starts from 2:00 p.m.. On your day of departure, you have time to leave your room until 11:00 a.m.. Early check-in and late check-out costs a thousand yen per. 2 Meeting registration Registration has to be done via website : https://www.regonline.com/builder/site/?eventid=2235732 Registration Fees - Early bird registration USD 700 Open on September 19 until November 16, 2018(PST) - Standard registration USD 800 From November 17, 2018 to January 4, 2019(PST) - Late/on Site registration USD 900 Open after January 4, 2019 to January 18, 2019(PST) The registration fee covers meeting fee, refreshments, coffee breaks, lunch, social event and Wi-Fi. Note: The registration fee includes VAT. Fee will be independent from staying at the meeting hotel. Registration payment policy Registration is payable through a secure website and requires a valid credit card for the payment of the registration fee; cash and checks are NOT accepted for registration. Any individual who attends any part of the IEEE 802.1 Interim Meeting must register and pay the full session fee. Session registrations are not transferable to another individual or to another interim session.