Article Full Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

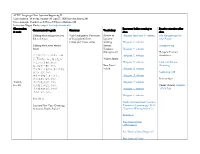

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II Class duration: 10 weeks, January 28–April 7, 2020 (no class March 24) Class meetings: Tuesdays at 5:30pm–7:30pm in Hellems 145 Instructor: Megan Husby, [email protected] Class session Resources before coming to Practice exercises after Communicative goals Grammar Vocabulary & topic class class Talking about things that you Verb Conjugation: Past tense Review of Hiragana Intro and あ column Fun Hiragana app for did in the past of long (polite) forms Japanese your Phone (~desu and ~masu verbs) Writing Hiragana か column Talking about your winter System: Hiragana song break Hiragana Hiragana さ column (Recognition) Hiragana Practice クリスマス・ハヌカー・お Hiragana た column Worksheet しょうがつ 正月はなにをしましたか。 Winter Sports どこにいきましたか。 Hiragana な column Grammar Review なにをたべましたか。 New Year’s (Listening) プレゼントをかいましたか/ Vocab Hiragana は column もらいましたか。 Genki I pg. 110 スポーツをしましたか。 Hiragana ま column だれにあいましたか。 Practice Quiz Week 1, えいがをみましたか。 Hiragana や column Jan. 28 ほんをよみましたか。 Omake (bonus): Kasajizō: うたをききましたか/ Hiragana ら column A Folk Tale うたいましたか。 Hiragana わ column Particle と Genki: An Integrated Course in Japanese New Year (Greetings, Elementary Japanese pgs. 24-31 Activities, Foods, Zodiac) (“Japanese Writing System”) Particle と Past Tense of desu (Affirmative) Past Tense of desu (Negative) Past Tense of Verbs Discussing family, pets, objects, Verbs for being (aru and iru) Review of Katakana Intro and ア column Katakana Practice possessions, etc. Japanese Worksheet Counters for people, animals, Writing Katakana カ column etc. System: Genki I pgs. 107-108 Katakana Katakana サ column (Recognition) Practice Quiz Katakana タ column Counters Katakana ナ column Furniture and common Katakana ハ column household items Katakana マ column Katakana ヤ column Katakana ラ column Week 2, Feb. -

The Degree of the Speaker's Negative Attitude in a Goal-Shifting

In Christopher Brown and Qianping Gu and Cornelia Loos and Jason Mielens and Grace Neveu (eds.), Proceedings of the 15th Texas Linguistics Society Conference, 150-169. 2015. The degree of the speaker’s negative attitude in a goal-shifting comparison Osamu Sawada∗ Mie University [email protected] Abstract The Japanese comparative expression sore-yori ‘than it’ can be used for shifting the goal of a conversation. What is interesting about goal-shifting via sore-yori is that, un- like ordinary goal-shifting with expressions like tokorode ‘by the way,’ using sore-yori often signals the speaker’s negative attitude toward the addressee. In this paper, I will investigate the meaning and use of goal-shifting comparison and consider the mecha- nism by which the speaker’s emotion is expressed. I will claim that the meaning of the pragmatic sore-yori conventionally implicates that the at-issue utterance is preferable to the previous utterance (cf. metalinguistic comparison (e.g. (Giannakidou & Yoon 2011))) and that the meaning of goal-shifting is derived if the goal associated with the at-issue utterance is considered irrelevant to the goal associated with the previous utterance. Moreover, I will argue that the speaker’s negative attitude is shown by the competition between the speaker’s goal and the hearer’s goal, and a strong negativity emerges if the goals are assumed to be not shared. I will also compare sore-yori to sonna koto-yori ‘than such a thing’ and show that sonna koto-yori directly expresses a strong negative attitude toward the previous utterance. -

MEDIATING SCANDAL in CONTEMPORARY JAPAN Igor

French Journal For Media Research – n° 7/2017 – ISSN 2264-4733 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ MEDIATING SCANDAL IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN Igor Prusa PhD The University of Tokyo, Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies1 [email protected] Abstract Cet article aborde des traits essentiels des affaires médiatiques dans le Japon contemporain. Il s'agit d'une étude interdisciplinaire qui enrichit non seulement le discours des sciences de médias et du journalisme, mais aussi la pholologie japonaise. L’inspiration théorique s'appuie sur la conception néo-fonctionnaliste du scandale en tant que performance sociale située à la limite du « rituel » (la conduite expressive à la motivation socioculturelle) et de la « stratégie » (une action stratégique délibéreée). La première partie de cette étude est consacrée aux caractéristiques du journalisme politique et du contexte médiatico-politique du Japon d’après-guerre. La seconde partie analyse le procès du scandale médiatique lui-même et quelques techniques ritualisées des organisations médiatiques japonaises. Mots-clés Médias japonais, pratiques de journalisme, affaire médiatique, rituel médiatique, procès de la scandalisation Abstract This paper investigates the main features of media scandal in contemporary Japan. This is important because it can add a fresh interdisciplinary direction in the fields of media studies, journalism, and Japanese philology. Furthermore, the sources from the mainstream media, semi-mainstream tabloids and foreign press were examined vie the lens of contemporary neofunctionalist theory, where scandal is approached as a social performance between ritual (motivated expressive behavior) and strategy (conscious strategic action). Moreover, this research illuminates the logic behind the scandal mediation process in Japan, including the performances of both the journalists and the non-media actors, who become decisive for the development of every media scandal. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Wobbly Aesthetics, Performance, and Message Comparing Japanese Kyara with Their Anthropomorphic Forebears

Debra J. Occhi Miyazaki International College Wobbly Aesthetics, Performance, and Message Comparing Japanese Kyara with their Anthropomorphic Forebears This article compares contemporary Japanese entities known as kyara (“char- acters”) with historical anthropomorphized imagery considered to be spiritual or religious. Yuru kyara (“loose” or “wobbly” characters) are a subcategory of kyara that represent places, events, or commodities, and occupy a relatively marginalized position within the larger body of kyara material culture. They are ubiquitous in contemporary Japan, and are sometimes enacted by humans in costume, as shown in a case study of a public event analyzed within. They are closely tied to localities and may be compared to historical deities and demons, situated as they are within the context of popular representations of the numinous created to inspire belief and spur action. However, the impera- tives communicated by yuru kyara are not typically religious per se, but civic and commercial. Religious charms and souvenirs also increasingly incorporate the kyara aesthetic. keywords: Japan—characters—cuteness—marketing—religion Asian Ethnology Volume 71, Number 1 • 2012, 109–132 © Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture his article explores possible connections between cute anthropomorphized Tcartoon characters (kyara) of domestic Japanese origin and use, and a long- standing tradition of anthropomorphized objects and animals used in spiritual or religious contexts. It broadly examines what similarities and discontinuities may be observed in comparing contemporary and historical anthropomorphized char- acters, their narratives, and their uses. This approach is not entirely original: the character Ultraman, for example, has elsewhere been likened to a Shinto savior of humanity (Gill 1998, 38). -

The State and Racialization: the Case of Koreans in Japan

The Center for Comparative Immigration Studies CCIS University of California, San Diego The State and Racialization: The Case of Koreans in Japan By Kazuko Suzuki Visiting Fellow, Center for Comparative Immigration Studies Working Paper 69 February 2003 The State and Racialization: The Case of Koreans in Japan Kazuko Suzuki1 Center for Comparative Immigration Studies ********** Abstract. It is frequently acknowledged that the notion of ‘race’ is a socio-political construct that requires constant refurbishment. However, the process and consequences of racialization are less carefully explored. By examining the ideology about nationhood and colonial policies of the Japanese state in relation to Koreans, I will attempt to demonstrate why and how the Japanese state racialized its population. By so doing, I will argue that the state is deeply involved in racialization by fabricating and authorizing ‘differences’ and ‘similarities’ between the dominant and minority groups. Introduction The last decade has seen a growing interest in the state within the field of sociology and political science. While the main contributors of the study have been scholars in comparative and historical sociology and researchers in the economics of development, student of race and ethnicity have gradually paid attention to the role of the state in forming racial/ethnic communities, ethnic identity, and ethnic mobilization (Barkey and Parikh 1991; Marx 1998). State policies clearly constitute one of the major determinants of immigrant adaptation and shifting identity patterns (Hein 1993; Olzak 1983; Nagel 1986). However, the study of the state’s role in race and ethnic studies is still underdeveloped, and many important questions remain to be answered. -

Telechargement

LA VERSION COMPLETE DE VOTRE GUIDE JAPON 2018/2019 en numérique ou en papier en 3 clics à partir de 9.99€ Disponible sur EDITION Directeurs de collection et auteurs : Bienvenue au Dominique AUZIAS et Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE Auteurs : Maxime DRAY, Barthélémy COURMONT, Antoine RICHARD, Matthieu POUGET-ABADIE, Arthur FOUCHERE, Maxence GORREGUES, Japon ! Jean-Marc WEISS, Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE, Dominique AUZIAS et alter Directeur Editorial : Stéphan SZEREMETA Responsable Editorial Monde : Patrick MARINGE Le Japon et ses habitants restent toujours un mystère fascinant Rédaction Monde : Caroline MICHELOT, Morgane pour la plupart d’entre nous. Les préjugés et les clichés, nous VESLIN, Pierre-Yves SOUCHET, Talatah FAVREAU le savons bien, ont la dent dure. Les Français ont la réputation Rédaction France : Elisabeth COL, Maurane d’être râleurs, prétentieux, et les Japonais insondables, trop CHEVALIER, Silvia FOLIGNO, Tony DE SOUSA polis même pour être sincères. Nous avons essayé dans cette FABRICATION nouvelle édition du guide Japon, plus complète, de vous donner Responsable Studio : Sophie LECHERTIER un éclairage global de la culture, des habitudes quotidiennes des assistée de Romain AUDREN Japonais, d’approcher ce magnifique pays sous divers aspects. Maquette et Montage : Julie BORDES, Le Japon possède une longue histoire, qui remonte aux Aïnous, Sandrine MECKING, Delphine PAGANO, une ethnie vivant sur l’île d’Hokkaido dans le nord du Japon dont Laurie PILLOIS et Noémie FERRON on a trouvé des traces vieilles de 12 000 ans ; et une modernité Iconographie : Anne DIOT incroyable en même temps, que l’on observe à chaque instant dans Cartographie : Jordan EL OUARDI les grandes métropoles nipponnes. L’archipel volcanique long de WEB ET NUMERIQUE plus de 3 000 kilomètres affiche une variété de paysages et de Directeur Web : Louis GENEAU de LAMARLIERE climats presque sans égale. -

A Performer's Guide to Minoru Miki's Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988)

University of Cincinnati Date: 4/22/2011 I, Margaret T Ozaki-Graves , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Voice. It is entitled: A Performer’s Guide to Minoru Miki’s _Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano_ (1988) Student's name: Margaret T Ozaki-Graves This work and its defense approved by: Committee chair: Jeongwon Joe, PhD Committee member: William McGraw, MM Committee member: Barbara Paver, MM 1581 Last Printed:4/29/2011 Document Of Defense Form A Performer’s Guide to Minoru Miki’s Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988) A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by Margaret Ozaki-Graves B.M., Lawrence University, 2003 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2007 April 22, 2011 Committee Chair: Jeongwon Joe, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Japanese composer Minoru Miki (b. 1930) uses his music as a vehicle to promote cross- cultural awareness and world peace, while displaying a self-proclaimed preoccupation with ethnic mixture, which he calls konketsu. This document intends to be a performance guide to Miki’s Sohmon III: for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988). The first chapter provides an introduction to the composer and his work. It also introduces methods of intercultural and artistic borrowing in the Japanese arts, and it defines the four basic principles of Japanese aesthetics. The second chapter focuses on the interpretation and pronunciation of Sohmon III’s song text. -

Section 18.1, Han

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

The Japanese Numeral Classifiers Hiki and Hatsu

Prototypes and Metaphorical Extensions: The Japanese Numeral Classifiers hiki and hatsu Hiroko Komatsu A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2018 Department of Japanese Studies School of Languages and Cultures Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Name: Hiroko Komatsu Signature: ……………………….. Date: ……..31 January 2018……. Abstract This study concerns the meaning of Japanese numeral classifiers (NCs) and, particularly, the elements which guide us to understand the metaphorical meanings they can convey. In the typological literature, as well as in studies of Japanese, the focus is almost entirely on NCs that refer to entities. NCs are generally characterised as being matched with a noun primarily based on semantic criteria such as the animacy, the physical characteristics, or the function of the referent concerned. However, in some languages, including Japanese, nouns allow a number of alternative NCs, so that it is considered that NCs are not automatically matched with a noun but rather with the referent that the noun refers to in the particular context in which it occurs. This study examines data from the Balanced Corpus of Contemporary Written Japanese, and focuses on two NCs as case studies: hiki, an entity NC, typically used to classify small, animate beings, and hatsu, an NC that is used to classify both entities and events that are typically explosive in nature. -

Japanese Approaches to the Meaning of Religion

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Faculty Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship Winter 1-1-2010 Beyond Belief: Japanese Approaches to the Meaning of Religion James Shields Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/fac_journ Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Shields, James. "Beyond Belief: Japanese Approaches to the Meaning of Religion." Studies in Religion / Sciences religieuses (2010) : 133-149. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Studies in Religion / Sciences Religieuses 000(00) 1–17 ª The Author(s) / Le(s) auteur(s), 2010 Beyond Belief: Japanese Reprints and permission/ Reproduction et permission: Approaches to the sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0008429810364118 Meaning of Religion sr.sagepub.com James Mark Shields Bucknell University, USA Abstract: For several centuries, Japanese scholars have argued that their nation’s culture—including its language, religion and ways of thinking—is somehow unique. The darker side of this rhetoric, sometimes known by the English term “Japanism” (nihon-jinron), played no small role in the nationalist fervor of the early late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. While much of the so-called “ideology of Japanese uniqueness” can be dismissed, in terms of the Japanese approach to “religion,” there may be something to it. -

Youth Handbook.Pub

AIKIDO OF M AINE 2010 THE AOM STUDENT H ANDBOOK F OR C HILDREN AIKIDO OF M AINE 226 Anderson street Portland, Maine 04101 Phone: 207-879-9207 E-mail: [email protected] Www.aikidoofmaine.com Teaching the martial art of peace to adults and children. PAGE 2 AIKIDO OF M AINE PAGE 15 23)P ARKING TABLE OF C ONTENTS Parking is available at the front of the dojo. In addition you can park on street. Please do not park in front of the bakery or block their trucks in 1) Welcome anyway. 2) Mission 3) What is Aikido 24)C AMERAS 4) Description Programs 5) Test process For the safety of our students, AOM reserves the right to use surveillance 6) Stripe achievement program cameras with in the school. Take photos and videos for the website and 7) Making training a priority other promotion. If there is any problem with this please let us know. 8) Web site / Face book 9) Referral and reward program / guess passes 24) GUIDELINES FOR OBSERVERS 10) Dojo 11) Teachers Please keep talking to a minimum or whisper when classes are in session. 12) Terms of Membership Students should have the maximum opportunity to hear the instructor and 13) Dojo events to keep their focus on the mat. Also please do not talk to your child or the instructor during class unless there is an emergency. 14) Dojo Store: dojo dollars, and coupons 15) Dojo Etiquette 16) Your uniform and personal cleanliness 25) READING RECOMENDATIONS 17) Keeping a Healthy dojo 18) Facility and dojo Routine 19) Getting involved For students interested in reading more about Aikido , please see the sug- gested reading list below.