Poetry: the Language of Love in Tale of Genji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Katsushika Hokusai and a Poetics of Nostalgia

ACCESS: CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN EDUCATION 2015, VOL. 33, NO. 1, 33–46 https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2014.964158 Katsushika Hokusai and a Poetics of Nostalgia David Bell College of Education, University of Otago ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article addresses the activation of aesthetics through the examination of cultural memory, Hokusai, an acute sensitivity to melancholy and time permeating the literary and ukiyo-e, poetic allusion, nostalgia, mono no aware pictorial arts of Japan. In medieval court circles, this sensitivity was activated through a pervasive sense of aware, a poignant reflection on the pathos of things. This sensibility became the motivating force for court verse, and ARTICLE HISTORY through this medium, for the mature projects of the ukiyo-e ‘floating world First published in picture’ artist Katsushika Hokusai. Hokusai reached back to aware sensibilities, Educational Philosophy and Theory, 2015, Vol. 47, No. 6, subjects and conventions in celebrations of the poetic that sustained cultural 579–595 memories resonating classical lyric and pastoral themes. This paper examines how this elegiac sensibility activated Hokusai’s preoccupations with poetic allusion in his late representations of scholar-poets and the unfinished series of Hyakunin isshu uba-ga etoki, ‘One hundred poems, by one hundred poets, explained by the nurse’. It examines four works to explain how their synthesis of the visual and poetic could sustain aware themes and tropes over time to maintain a distinctive sense of this aesthetic sensibility in Japan. Introduction: Mono no aware How can an aesthetic sensibility become an activating force in and through poetic and pictorial amalgams of specific cultural histories and memories? This article examines how the poignant aesthetic sensibility of mono no aware (a ‘sensitivity to the pathos of things’) established a guiding inflection for social engagements of the Heian period (794–1185CE) Fujiwara court in Japan. -

The Hyakunin Isshu Translated Into Danish

The Hyakunin Isshu translated into Danish Inherent difficulties in translation and differences from English & Swedish versions By Anna G Bouchikas [email protected] Bachelor Thesis Lund University Japanese Centre for Languages and Literature, Japanese Studies Spring Term 2017 Supervisor: Shinichiro Ishihara ABSTRACT In this thesis, translation of classic Japanese poetry into Danish will be examined in the form of analysing translations of the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. Difficulties will be surveyed, and ways of handling them will be suggested. Furthermore, differences between the Danish translations and those of English and Swedish translations will be noted. Relevant translation methods will be presented, as well as an introduction to translation, to further the understanding of the reader in the discussion. The hypothesis for this study was that when translating the Hyakunin Isshu into Danish, the translator would be forced to make certain compromises. The results supported this hypothesis. When translating from Japanese to Danish, the translator faces difficulties such as following the metre, including double meaning, cultural differences and special features of Japanese poetry. To adequately deal with these difficulties, the translator must be willing to compromise in the final translation. Which compromises the translator must make depends on the purpose of the translation. Keywords: translation; classical Japanese; poetry; Ogura Hyakunin Isshu; Japanese; Danish; English; Swedish ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank both of my informants for being willing to spend as much time helping me as they have. Had they not taken the time they did to answer all of my never- ending questions, surely I would still be doing my study even now. -

“Hyakunin Isshu” – the Most Famous Anthology of Poems 2018.11.1(Thu) – 2019.5.12(Sun)

“Hyakunin Isshu” – the most famous anthology of poems 2018.11.1(Thu) – 2019.5.12(Sun) “Hyakunin Isshu” (One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each) – is a famous anthology of Japanese Waka poems. It is a collection of one hundred original poems spanning one hundred poets. However, the one edited by Fujiwara no Teika (1162 – 1241) in the 13th century Kamakura period became so popular that Teika’s edition has been simply called “Hyakunin Isshu” since then. Teika’s edition is also called “Ogura Hyakunin Isshu”, as it is said that Teika chose them in his cottage at the foot of Mt. Ogura, which is located near this museum. Saga Arashiyama is the home of “Hyakunin Isshu” which gave a great influence on Japanese culture, even on the modern culture such as manga or anime. In this exhibition, you can learn its history and 100 poems with pretty dolls representing all poets. All the exhibits have English translation. We hope you enjoy the world of “Hyakunin Isshu.” Admission Fee: Individual Group (over 20) Adults (> 19) 900 800 High School Students (16 to 18) 500 400 Elementary & Junior High School Students 300 250 (7 to 15) A person with disability and an attendant 500 400 Children under the age of 7 are free Including admission fee for the special exhibition Membership: Annual Fee 3,000 yen One annual passport per member(free entrance for SAMAC) Discount for paid events at SAMAC Free English Guide Tour for a group (about 30min) Reservation required in advance Access: Nice 3 minutes walk from Togetsu bridge, next to the Luxury Collection Suiran hotel Close to Chou En Lai Monument and Hogoin Temple 5 minutes walk from Randen Arashiyama Station 15 minutes walk from JR Saga Arashiyama Station / Hankyu Arashiyama Station 11 Sagatenryuji-Susukinobabacho 11, Ukyo-ku, Kyoto 616-8385 SAMAC Contact: [email protected] +81-75-882-1111 (English speaker available) . -

Japanese Aesthetics and the Tale of Genji Liya Li Department of English SUNY/Rockland Community College [email protected] T

Japanese Aesthetics and The Tale of Genji Liya Li Department of English SUNY/Rockland Community College [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Themes and Uses 2. Instructor’s Introduction 3. Student Readings 4. Discussion Questions 5. Sample Writing Assignments 6. Further Reading and Resources 1. Themes and Uses Using an excerpt from the chapter “The Sacred Tree,” this unit offers a guide to a close examination of Japanese aesthetics in The Tale of Genji (ca.1010). This two-session lesson plan can be used in World Literature courses or any course that teaches components of Zen Buddhism or Japanese aesthetics (e.g. Introduction to Buddhism, the History of Buddhism, Philosophy, Japanese History, Asian Literature, or World Religion). Specifically, the lesson plan aims at helping students develop a deeper appreciation for both the novel and important concepts of Japanese aesthetics. Over the centuries since its composition, Genji has been read through the lenses of some of the following terms, which are explored in this unit: • miyabi (“courtly elegance”; refers to the aristocracy’s privileging of a refined aesthetic sensibility and an indirectness of expression) • mono no aware (the “poignant beauty of things;” describes a cultivated sensitivity to the ineluctable transience of the world) • wabi-sabi (wabi can be translated as “rustic beauty” and sabi as “desolate beauty;” the qualities usually associated with wabi and sabi are austerity, imperfection, and a palpable sense of the passage of time. • yûgen (an emotion, a sentiment, or a mood so subtle and profoundly elegant that it is beyond what words can describe) For further explanation of these concepts, see the unit “Buddhism and Japanese Aesthetics” (forthcoming on the ExEAS website.) 2. -

Positive Psychology – Unmitigated Good, and Pessimism As a Categorical Impediment to Wellbeing

E L C I contrasting phenomena were implicitly T conceptualised as negative, positioned as R intrinsically undesirable. So, for example, A optimism tended to be valorised as an Positive psychology – unmitigated good, and pessimism as a categorical impediment to wellbeing. Some scholars did paint a more nuanced the second wave picture; for instance, Seligman (1990, p.292) cautioned that one must be ‘able Tim Lomas delves into the dialectical nuances of flourishing to use pessimism’s keen sense of reality when we need it’. However, in terms of the broader discourse of the field, and its cultural impact, a less nuanced binary t is nearly 20 years since Martin wellbeing – could be brought together message held sway. Seligman used his American and considered collectively. Thus, as While seemingly offering an upbeat IPsychological Association presidential a novel branch of scholarship focused message – linking positive emotions to address to inaugurate the notion of specifically and entirely on ‘the science beneficial outcomes, such as health ‘positive psychology’. The rationale for its and practice of improving wellbeing’ (Fredrickson & Levenson, 1998) – this creation was Seligman’s contention that (Lomas et al., 2015, p.1347), it was valorisation of positivity was problematic, psychology had tended to focus mainly a welcome new addition to the broader for various reasons. Firstly, it often failed on what is wrong with people: on church of psychology. to sufficiently appreciate the contextual dysfunction, disorder and distress. There However, positive psychology was complexity of emotional outcomes. For were of course pockets of scholarship that not without its critics. A prominent instance, ‘excessive’ optimism can be held a candle for human potential and focus of concern was the very notion harmful to wellbeing (e.g. -

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II

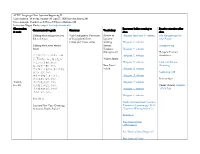

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II Class duration: 10 weeks, January 28–April 7, 2020 (no class March 24) Class meetings: Tuesdays at 5:30pm–7:30pm in Hellems 145 Instructor: Megan Husby, [email protected] Class session Resources before coming to Practice exercises after Communicative goals Grammar Vocabulary & topic class class Talking about things that you Verb Conjugation: Past tense Review of Hiragana Intro and あ column Fun Hiragana app for did in the past of long (polite) forms Japanese your Phone (~desu and ~masu verbs) Writing Hiragana か column Talking about your winter System: Hiragana song break Hiragana Hiragana さ column (Recognition) Hiragana Practice クリスマス・ハヌカー・お Hiragana た column Worksheet しょうがつ 正月はなにをしましたか。 Winter Sports どこにいきましたか。 Hiragana な column Grammar Review なにをたべましたか。 New Year’s (Listening) プレゼントをかいましたか/ Vocab Hiragana は column もらいましたか。 Genki I pg. 110 スポーツをしましたか。 Hiragana ま column だれにあいましたか。 Practice Quiz Week 1, えいがをみましたか。 Hiragana や column Jan. 28 ほんをよみましたか。 Omake (bonus): Kasajizō: うたをききましたか/ Hiragana ら column A Folk Tale うたいましたか。 Hiragana わ column Particle と Genki: An Integrated Course in Japanese New Year (Greetings, Elementary Japanese pgs. 24-31 Activities, Foods, Zodiac) (“Japanese Writing System”) Particle と Past Tense of desu (Affirmative) Past Tense of desu (Negative) Past Tense of Verbs Discussing family, pets, objects, Verbs for being (aru and iru) Review of Katakana Intro and ア column Katakana Practice possessions, etc. Japanese Worksheet Counters for people, animals, Writing Katakana カ column etc. System: Genki I pgs. 107-108 Katakana Katakana サ column (Recognition) Practice Quiz Katakana タ column Counters Katakana ナ column Furniture and common Katakana ハ column household items Katakana マ column Katakana ヤ column Katakana ラ column Week 2, Feb. -

Poetic Constraints of Lyric by Nicholas Andrew Theisen a Dissertation

Re[a]ding and Ignorance: Poetic Constraints of Lyric by Nicholas Andrew Theisen A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Professor E. Ramirez-Christensen, Chair Professor Marjorie Levinson Associate Professor Johanna H. Prins Associate Professor Joseph D. Reed © Nicholas Andrew Theisen 2009 For no one ii Acknowledgements The work concluded, tentatively, with this dissertation would not have been possible without the continued intellectual engagement with my colleagues within and without the Department of Comparative Literature at the University of Michigan, especially (in no particular order) Michael Kicey, Meng Liansu, Sylwia Ejmont, Carrie Wood, and Sharon Marquart. I have benefited much from Jay Reed’s friendly antagonism, Marjorie Levinson’s keen insight, Esperanza Ramirez-Christensen’s grounding levity, and Yopie Prins’s magnanimity. But beyond the academic sphere, more or less, I’m am deeply indebted to Kobayashi Yasuko for reminding me that, to some, poetry matters as more than a mere figure of academic discourse and to my wife Colleen for her wholly unexpected insights and seemingly infinite patience. I have likely forgotten to mention numerous people; consider this my I.O.U. on a free drink. iii Table of Contents Dedication ii Acknowledgements iii List of Abbreviations vi List of Figures vii Chapters 1. Introduction 1 2. The Edges of Anne Carson’s Sappho 24 The Fragments of [Anne] Carson 27 Mutilation 45 3. Chocolate Bittersweet: Tawara Machi Translating Yosano Akiko 69 Bitter 71 Sweet 97 4. Separate but Equal: [un]Equating Catullus with Sappho 110 Impar 115 Par 128 Silence 140 5. -

The Degree of the Speaker's Negative Attitude in a Goal-Shifting

In Christopher Brown and Qianping Gu and Cornelia Loos and Jason Mielens and Grace Neveu (eds.), Proceedings of the 15th Texas Linguistics Society Conference, 150-169. 2015. The degree of the speaker’s negative attitude in a goal-shifting comparison Osamu Sawada∗ Mie University [email protected] Abstract The Japanese comparative expression sore-yori ‘than it’ can be used for shifting the goal of a conversation. What is interesting about goal-shifting via sore-yori is that, un- like ordinary goal-shifting with expressions like tokorode ‘by the way,’ using sore-yori often signals the speaker’s negative attitude toward the addressee. In this paper, I will investigate the meaning and use of goal-shifting comparison and consider the mecha- nism by which the speaker’s emotion is expressed. I will claim that the meaning of the pragmatic sore-yori conventionally implicates that the at-issue utterance is preferable to the previous utterance (cf. metalinguistic comparison (e.g. (Giannakidou & Yoon 2011))) and that the meaning of goal-shifting is derived if the goal associated with the at-issue utterance is considered irrelevant to the goal associated with the previous utterance. Moreover, I will argue that the speaker’s negative attitude is shown by the competition between the speaker’s goal and the hearer’s goal, and a strong negativity emerges if the goals are assumed to be not shared. I will also compare sore-yori to sonna koto-yori ‘than such a thing’ and show that sonna koto-yori directly expresses a strong negative attitude toward the previous utterance. -

©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori

1 ©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori 2 Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Paul S. Atkins, Chair Davinder L. Bhowmik Tani E. Barlow Kyoko Tokuno Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Asian Languages and Literature 3 University of Washington Abstract Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Paul S. Atkins Asian Languages and Literature This study is an attempt to elucidate the complex interrelationship between gender, sexuality, desire, and power by examining how premodern Japanese texts represent the gender-based ideals of women and men at the peak and margins of the social hierarchy. To do so, it will survey a wide range of premodern texts and contrast the literary depictions of two female groups (imperial priestesses and courtesans), two male groups (elite warriors and outlaws), and two groups of Buddhist priests (elite and “corrupt” monks). In my view, each of the pairs signifies hyperfemininities, hypermasculinities, and hypersexualities of elite and outcast classes, respectively. The ultimate goal of 4 this study is to contribute to the current body of research in classical Japanese literature by offering new readings of some of the well-known texts featuring the above-mentioned six groups. My interpretations of the previously studied texts will be based on an argument that, in a cultural/literary context wherein defiance merges with sexual attractiveness and/or sexual freedom, one’s outcast status transforms into a source of significant power. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Reading and Re-Envisioning the Tale of Genji Through the Ages

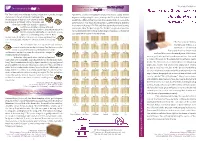

Symbols of each chapters of The Tale of Genji Thematic Exhibition Ⅳ Dissemination of the Genji Tale from the Genji-kō Incense Game Reading and Re-envisioning The Tale of Genji attracted many readers, irrespective of gender, through "Genji-kō" is a name of the kumikō incense game which is tasting different the beauty of the text and its thorough depictions fragrances and guessing the name, developed in Edo period. Participants The Tale of Genji of every aspect of classical court culture, its skillful would taste 5 different fragrances and draw a horizontal line to connect the psychological portrayals of the characters, and same fragrance. Thus drawn, figures appear in 52 different shapes, matching through the Ages its diverse world view based on Japanese the number of chapters of The Tale of Genji except the first and the last ones, and Chinese literature, various arts, and and they are called "Genji-kō" design. The "Genji-kō" design often appears in Buddhism. Not only did it have a significant impact on various traditional craft works as well as design of Japanese confectionery later literary works, but its influence can also be seen in associated with the story of The Tale of Genji. Japanese performing arts, such as Noh theater, and cultural arts, such as incense ceremony (kōdō), and tea ceremony (sadō), as well as the arts and crafts that accompany them. 46 37 28 1 9 1 0 1 “The Tale of Genji,” written Shiigamoto Yokobue Nowaki Usugumo Sakaki Kiritsubo At the same time, as a narrative that features Art Museum & The Tokugawa 2020 / By Hōsa Library, City of Nagoya Nov. -

Noh Theater and Religion in Medieval Japan

Copyright 2016 Dunja Jelesijevic RITUALS OF THE ENCHANTED WORLD: NOH THEATER AND RELIGION IN MEDIEVAL JAPAN BY DUNJA JELESIJEVIC DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in East Asian Languages and Cultures in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Elizabeth Oyler, Chair Associate Professor Brian Ruppert, Director of Research Associate Professor Alexander Mayer Professor Emeritus Ronald Toby Abstract This study explores of the religious underpinnings of medieval Noh theater and its operating as a form of ritual. As a multifaceted performance art and genre of literature, Noh is understood as having rich and diverse religious influences, but is often studied as a predominantly artistic and literary form that moved away from its religious/ritual origin. This study aims to recapture some of the Noh’s religious aura and reclaim its religious efficacy, by exploring the ways in which the art and performance of Noh contributed to broader religious contexts of medieval Japan. Chapter One, the Introduction, provides the background necessary to establish the context for analyzing a selection of Noh plays which serve as case studies of Noh’s religious and ritual functioning. Historical and cultural context of Noh for this study is set up as a medieval Japanese world view, which is an enchanted world with blurred boundaries between the visible and invisible world, human and non-human, sentient and non-sentient, enlightened and conditioned. The introduction traces the religious and ritual origins of Noh theater, and establishes the characteristics of the genre that make it possible for Noh to be offered up as an alternative to the mainstream ritual, and proposes an analysis of this ritual through dynamic and evolving schemes of ritualization and mythmaking, rather than ritual as a superimposed structure.