Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera Austiniae) in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November December 2010 Vol 67.3 Victoria Natural

NOVEMBER DECEMBER 2010 VOL 67.3 VICTORIA NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY The Victoria Naturalist Vol. 67.3 (2010) 1 Published six times a year by the SUBMISSIONS VICTORIA NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY, P.O. Box 5220, Station B, Victoria, BC V8R 6N4 Deadline for next issue: December 1, 2010 Contents © 2010 as credited. Send to: Claudia Copley ISSN 0049—612X Printed in Canada 657 Beaver Lake Road, Victoria BC V8Z 5N9 Editors: Claudia Copley, 250-479-6622, Penelope Edwards Phone: 250-479-6622 Desktop Publishing: Frances Hunter, 250-479-1956 e-mail: [email protected] Distribution: Tom Gillespie, Phyllis Henderson, Morwyn Marshall Printing: Fotoprint, 250-382-8218 Guidelines for Submissions Opinions expressed by contributors to The Victoria Naturalist Members are encouraged to submit articles, field trip reports, natural are not necessarily those of the Society. history notes, and book reviews with photographs or illustrations if possible. Photographs of natural history are appreciated along with VICTORIA NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY documentation of location, species names and a date. Please label your Honorary Life Members Dr. Bill Austin, Mrs. Lyndis Davis, submission with your name, address, and phone number and provide a Mr. Tony Embleton, Mr. Tom Gillespie, Mrs. Peggy Goodwill, title. We request submission of typed, double-spaced copy in an IBM compatible word processing file on diskette, or by e-mail. Photos and Mr. David Stirling, Mr. Bruce Whittington slides, and diskettes submitted will be returned if a stamped, self- Officers: 2009-2010 addressed envelope is included with the material. Digital images are PRESIDENT: Darren Copley, 250-479-6622, [email protected] welcome, but they need to be high resolution: a minimum of 1200 x VICE-PRESIDENT: James Miskelly, 250-477-0490, [email protected] 1550 pixels, or 300 dpi at the size of photos in the magazine. -

Physiological Features of the Terrestrial Orchids

Anallelle Uniiversiităţiiii diin Craiiova, seriia Agriiculltură – Montanollogiie – Cadastru (Annalls of the Uniiversiity of Craiiova - Agriicullture, Montanollogy, Cadastre Seriies)Voll. XLIX/2019 PHYSIOLOGICAL FEATURES OF THE TERRESTRIAL ORCHIDS CEPHALANTHERA LONGIFOLIA AND PLATANTHERA BIFOLIA THAT GROW IN THE PEDO-CLIMATIC CONDITIONS FROM OLTENIA REGION OF ROMANIA BUSE-DRAGOMIR LUMINITA (1), NICOLAE ION (2), NICULESCU MARIANA (3) (1) University of Craiova, E-mail: [email protected] (2) University of Craiova, E-mail: [email protected] (3) University of Craiova, E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author email: [email protected] Key words: terrestrial orchids, transpiration, photosynthesis, light ABSTRACT For studying the physiology of terrestrial orchids, plants from the species Cephalanthera longifolia and Platanthera bifolia have been used. The experiences were carried out directly on the field, in Mehedinţi County, Comanesti Hills. In both species of orchids, the seasonal dynamics of photosynthesis registers a peak during the flowering period that corresponds to a maximum content of assimilating pigments and also a maximum leaf surface. In terrestrial orchids, the seasonal dynamics of leaf transpiration intensity is highest during spring, when the water content in the soil is high and minimal in summer. The graphs showing the diurnal variation of photosynthesis for the two species indicate that Cephalanthera longifolia prefers semi-shaded and sunny habitats, while the plants of Platanthera bifolia that are found in the studied areas prefer a more shaded environment INTRODUCTION Orchids that grow directly at the two, more or less globular or digitally- ground level in large areas of Europe or branched tubules. From the main tuber on the grasslands of the tropical regions comes the flowering stem. -

Willi Orchids

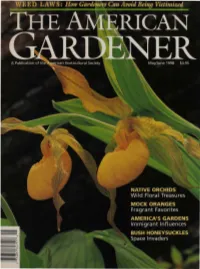

growers of distinctively better plants. Nunured and cared for by hand, each plant is well bred and well fed in our nutrient rich soil- a special blend that makes your garden a healthier, happier, more beautiful place. Look for the Monrovia label at your favorite garden center. For the location nearest you, call toll free l-888-Plant It! From our growing fields to your garden, We care for your plants. ~ MONROVIA~ HORTICULTURAL CRAFTSMEN SINCE 1926 Look for the Monrovia label, call toll free 1-888-Plant It! co n t e n t s Volume 77, Number 3 May/June 1998 DEPARTMENTS Commentary 4 Wild Orchids 28 by Paul Martin Brown Members' Forum 5 A penonal tour ofplaces in N01,th America where Gaura lindheimeri, Victorian illustrators. these native beauties can be seen in the wild. News from AHS 7 Washington, D . C. flower show, book awards. From Boon to Bane 37 by Charles E. Williams Focus 10 Brought over f01' their beautiful flowers and colorful America)s roadside plantings. berries, Eurasian bush honeysuckles have adapted all Offshoots 16 too well to their adopted American homeland. Memories ofgardens past. Mock Oranges 41 Gardeners Information Service 17 by Terry Schwartz Magnolias from seeds, woodies that like wet feet. Classic fragrance and the ongoing development of nell? Mail-Order Explorer 18 cultivars make these old favorites worthy of considera Roslyn)s rhodies and more. tion in today)s gardens. Urban Gardener 20 The Melting Plot: Part II 44 Trial and error in that Toddlin) Town. by Susan Davis Price The influences of African, Asian, and Italian immi Plants and Your Health 24 grants a1'e reflected in the plants and designs found in H eading off headaches with herbs. -

Forma Nov.: a New Peloric Orchid from Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan

The Japanese Society for Plant Systematics ISSN 1346-7565 Acta Phytotax. Geobot. 65 (3): 127–139 (2014) Cephalanthera falcata f. conformis (Orchidaceae) forma nov.: A New Peloric Orchid from Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan 1,* 1 1 HirosHi Hayakawa , CHiHiro Hayakawa , yosHinobu kusumoto , tomoko 1 1 2 3,4 nisHida , Hiroaki ikeda , tatsuya Fukuda and Jun yokoyama 1National Institute for Agro-Environmental Sciences, 3-1-3 Kannondai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8604, Japan. *[email protected] (author for correspondences); 2Faculty of Agriculture, Kochi University, Nan- koku, Kochi 783-8502, Japan; 3Faculty of Science, Yamagata University, Kojirakawa, Yamagata 990-8560, Japan; 4Institute for Regional Innovation, Yamagata University, Kaminoyama, Yamagata 999-3101, Japan We recognize a new peloric form of the orchid Cephalanthera falcata (Thunb.) Blume f. conformis Hi- ros. Hayak. et J. Yokoy., which occurs in the vicinity of the Tsukuba mountain range in Ibaraki Prefec- ture, Japan. This peloric form is sympatric with C. falcata f. falcata. The peloric flowers have a petal-like lip. The flowers are radially symmetrical and the perianth parts spread weakly compared to normal flow- ers. The stigmas are positioned at the column apex, thus neighboring stigmas and the lower parts of the pollinia are conglutinated. We observed similar vegetative traits among C. falcata f. falcata, C. falcata f. albescens S. Kobayashi, and C. falcata f. conformis. The floral morphology in C. falcata f. conformis resembles that of C. nanchuanica (S.C. Chen) X.H. Jin et X.G. Xiang (i.e., similar petal-like lip and stig- ma position at the column apex; syn. Tangtsinia nanchuanica S.C. -

Phytogeographical Analysis and Ecological Factors of the Distribution of Orchidaceae Taxa in the Western Carpathians (Local Study)

plants Article Phytogeographical Analysis and Ecological Factors of the Distribution of Orchidaceae Taxa in the Western Carpathians (Local study) Lukáš Wittlinger and Lucia Petrikoviˇcová * Department of Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, 94974 Nitra, Slovakia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +421-907-3441-04 Abstract: In the years 2018–2020, we carried out large-scale mapping in the Western Carpathians with a focus on determining the biodiversity of taxa of the family Orchidaceae using field biogeographical research. We evaluated the research using phytogeographic analysis with an emphasis on selected ecological environmental factors (substrate: ecological land unit value, soil reaction (pH), terrain: slope (◦), flow and hydrogeological productivity (m2.s−1) and average annual amounts of global radiation (kWh.m–2). A total of 19 species were found in the area, of which the majority were Cephalenthera longifolia, Cephalenthera damasonium and Anacamptis morio. Rare findings included Epipactis muelleri, Epipactis leptochila and Limodorum abortivum. We determined the ecological demands of the abiotic environment of individual species by means of a functional analysis of communities. The research confirmed that most of the orchids that were studied occurred in acidified, calcified and basophil locations. From the location of the distribution of individual populations, it is clear that they are generally arranged compactly and occasionally scattered, which results in ecological and environmental diversity. During the research, we identified 129 localities with the occurrence of Citation: Wittlinger, L.; Petrikoviˇcová, L. Phytogeographical Analysis and 19 species and subspecies of orchids. We identify the main factors that threaten them and propose Ecological Factors of the Distribution specific measures to protect vulnerable populations. -

SOUTH COAST CONSERVATION PROGRAM Protecting and Restoring at Risk Species and Ecological Communities on BC’S South Coast

British Columbia’s Coast Region Species and Ecological Communities of Conservation Concern SOUTH COAST CONSERVATION PROGRAM Protecting and Restoring at Risk species and Ecological Communities on BC’s South Coast SPECIES PROFILE: Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae), Family Orchidaceae “orchids” Status Global: G4 Provincial: S2 SARA: 1-Threatened BC List: Red A member of the family Orchidaceae (“orchids”), phantom or “snow” orchid as it is sometimes referred to is the only species of the genus Cephalanthera found outside of Europe and Asia. A “myco-heterotrophic” species it lacks chlorophyll and is unable to photosynthesize. Phantom orchid obtains nutrients through a three-way partnership with fungi in the family Thelophoraceae and a tree species (presently unidentified). To facilitate this unique and complex relationship, the majority of the plants structure is underground; exact occurrences and distribution can be variable and difficult to predict from year to year as conditions change. As well plants may become dormant for a period of time making definitive distribution and occurrence locations problematic. Phantom Orchid Characteristics Height up to 65 cm. Phantom orchid is a white, non-photosynthetic, (things to look for) rhizomatous perennial. Flowering stems have 5-20 vanilla scented white flowers, each with a yellow gland on the lower lip. The 2-5 bract-like leaves are present along the stem. The stems turn yellowish or brownish as they age. After flowering, dry, seed-bearing capsules may form. Indian pipe (Monotropa uniflora) is a similar looking, white, non- Looks like (Similar) photosynthetic perennial that occurs in the same types of habitats as phantom orchid. The two species can easily be distinguished because phantom orchid has numerous upright flowers on each stem and the flowers bear a yellow gland on the lower petal. -

Phylogeny, Character Evolution and the Systematics of Psilochilus (Triphoreae)

THE PRIMITIVE EPIDENDROIDEAE (ORCHIDACEAE): PHYLOGENY, CHARACTER EVOLUTION AND THE SYSTEMATICS OF PSILOCHILUS (TRIPHOREAE) A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Erik Paul Rothacker, M.Sc. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Doctoral Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. John V. Freudenstein, Adviser Dr. John Wenzel ________________________________ Dr. Andrea Wolfe Adviser Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology Graduate Program COPYRIGHT ERIK PAUL ROTHACKER 2007 ABSTRACT Considering the significance of the basal Epidendroideae in understanding patterns of morphological evolution within the subfamily, it is surprising that no fully resolved hypothesis of historical relationships has been presented for these orchids. This is the first study to improve both taxon and character sampling. The phylogenetic study of the basal Epidendroideae consisted of two components, molecular and morphological. A molecular phylogeny using three loci representing each of the plant genomes including gap characters is presented for the basal Epidendroideae. Here we find Neottieae sister to Palmorchis at the base of the Epidendroideae, followed by Triphoreae. Tropidieae and Sobralieae form a clade, however the relationship between these, Nervilieae and the advanced Epidendroids has not been resolved. A morphological matrix of 40 taxa and 30 characters was constructed and a phylogenetic analysis was performed. The results support many of the traditional views of tribal composition, but do not fully resolve relationships among many of the tribes. A robust hypothesis of relationships is presented based on the results of a total evidence analysis using three molecular loci, gap characters and morphology. Palmorchis is placed at the base of the tree, sister to Neottieae, followed successively by Triphoreae sister to Epipogium, then Sobralieae. -

Vascular Plants of Santa Cruz County, California

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST of the VASCULAR PLANTS of SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, CALIFORNIA SECOND EDITION Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland & Maps by Ben Pease CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY, SANTA CRUZ COUNTY CHAPTER Copyright © 2013 by Dylan Neubauer All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the author. Design & Production by Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland Maps by Ben Pease, Pease Press Cartography (peasepress.com) Cover photos (Eschscholzia californica & Big Willow Gulch, Swanton) by Dylan Neubauer California Native Plant Society Santa Cruz County Chapter P.O. Box 1622 Santa Cruz, CA 95061 To order, please go to www.cruzcps.org For other correspondence, write to Dylan Neubauer [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-615-85493-9 Printed on recycled paper by Community Printers, Santa Cruz, CA For Tim Forsell, who appreciates the tiny ones ... Nobody sees a flower, really— it is so small— we haven’t time, and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. —GEORGIA O’KEEFFE CONTENTS ~ u Acknowledgments / 1 u Santa Cruz County Map / 2–3 u Introduction / 4 u Checklist Conventions / 8 u Floristic Regions Map / 12 u Checklist Format, Checklist Symbols, & Region Codes / 13 u Checklist Lycophytes / 14 Ferns / 14 Gymnosperms / 15 Nymphaeales / 16 Magnoliids / 16 Ceratophyllales / 16 Eudicots / 16 Monocots / 61 u Appendices 1. Listed Taxa / 76 2. Endemic Taxa / 78 3. Taxa Extirpated in County / 79 4. Taxa Not Currently Recognized / 80 5. Undescribed Taxa / 82 6. Most Invasive Non-native Taxa / 83 7. Rejected Taxa / 84 8. Notes / 86 u References / 152 u Index to Families & Genera / 154 u Floristic Regions Map with USGS Quad Overlay / 166 “True science teaches, above all, to doubt and be ignorant.” —MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO 1 ~ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ~ ANY THANKS TO THE GENEROUS DONORS without whom this publication would not M have been possible—and to the numerous individuals, organizations, insti- tutions, and agencies that so willingly gave of their time and expertise. -

Networks in a Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analysis: Reconstructing Evolutionary History of Asparagales (Lilianae) Based on Four Plastid Genes

Networks in a Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analysis: Reconstructing Evolutionary History of Asparagales (Lilianae) Based on Four Plastid Genes Shichao Chen1., Dong-Kap Kim2., Mark W. Chase3, Joo-Hwan Kim4* 1 College of Life Science and Technology, Tongji University, Shanghai, China, 2 Division of Forest Resource Conservation, Korea National Arboretum, Pocheon, Gyeonggi- do, Korea, 3 Jodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom, 4 Department of Life Science, Gachon University, Seongnam, Gyeonggi-do, Korea Abstract Phylogenetic analysis aims to produce a bifurcating tree, which disregards conflicting signals and displays only those that are present in a large proportion of the data. However, any character (or tree) conflict in a dataset allows the exploration of support for various evolutionary hypotheses. Although data-display network approaches exist, biologists cannot easily and routinely use them to compute rooted phylogenetic networks on real datasets containing hundreds of taxa. Here, we constructed an original neighbour-net for a large dataset of Asparagales to highlight the aspects of the resulting network that will be important for interpreting phylogeny. The analyses were largely conducted with new data collected for the same loci as in previous studies, but from different species accessions and greater sampling in many cases than in published analyses. The network tree summarised the majority data pattern in the characters of plastid sequences before tree building, which largely confirmed the currently recognised phylogenetic relationships. Most conflicting signals are at the base of each group along the Asparagales backbone, which helps us to establish the expectancy and advance our understanding of some difficult taxa relationships and their phylogeny. -

Woodard Bay Natural Resources Conservation Area Vascular Plant List

Woodard Bay Natural Resources Conservation Area Vascular Plant List Courtesy of DNR staff and the Washington Native Plant Society. Nomenclature follows Flora of the Pacific Northwest 2nd Edition (2018). * - Introduced Genus/Species Common Name Plant Family Abies grandis Grand fir Pinaceae Acer circinatum Vine maple Sapindaceae Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf maple Sapindaceae Achillea millefolium Common yarrow Asteraceae Achlys triphylla Vanilla leaf Berberidaceae Actaea rubra Baneberry Ranunculacae Adenocaulon bicolor Path finder, trail plant Asteraceae Adiantum aleuticum (A. pedantum) Northern maidenhair fern Pteridaceae Agrostis exarata Spike bentgrass Poaceae Aira caryophyllea* Silver hairgrass Poaceae Amelanchier alnifolia Western serviceberry, saskatoon Rosaceae Anaphalis margaritacea Pearly everlasting Asteraceae Anthemis cotula* Stinking chamomile, mayweed chamomile Asteraceae Aquilegia formosa Red columbine Ranunculaceae Arbutus menziesii Pacific madrone Ericaceae Arctostaphylos uva-ursi Kinnikinnick Ericaceae Arctium minus* Common burdock Asteraceae Arum italicum* Italian arum Araceae Asarum caudatum Wild ginger Aristolochiaceae Athyrium filix-femina Common lady fern, northern lady fern Athyriaceae Atriplex patula* Saltbush, spearscale Amaranthaceae Bellis perennis* English lawn daisy Asteraceae Mahonia aquifolium Tall Oregon grape Berberidaceae Mahonia nervosa Dull Oregon-grape, Low Oregon-grape Berberidaceae Struthiopteris spicant Deer fern Blechnaceae Brassica nigra* Black mustard Brassicaceae Bromus spp** Brome grasses Poaceae -

1 Plants Without Green Leaves and Stems………………..………………………………

James P. Riser II – Idaho/WesternWA Orchid Workshop INPS 7 March 2009 - 1 - Key to Orchidaceae genera of Idaho and western Washington: 1 Plants without green leaves and stems………………..………………………………... 2 1 Plants with green leaves and green stems…………………...…………………………. 3 2 Plants pure white with yellow spot on lip…………………….. Cephalanthera austiniae 2 Plants reddish, yellowish, or greenish (if white, no yellow spot on lip)…... Corallorhiza 3 Lip an inflated sac-like pouch……………………………………………... Cypripedium 3 Lip not an inflated sac-like pouch……………………………………………………… 4 4 Lip with a slender to saccate spur at base……………………………………………… 5 4 Lip lacking a spur……………………………………………………………………… 7 5 Leaves present at flowering; sepals with 3+ nerves…………………………………… 6 5 Leaves generally withering at flowering; sepals with 1 nerve…………………. Piperia 6 Lip trifid, tip divided into two larger and one smaller central tooth Coeloglossum viride 6 Lip not trifid, tip not divided into three teeth………………………………. Platanthera 7 Leaves single, lip slipper-like with tuft of hair…………………………Calypso bulbosa 7 Leaves 2 or more, lip not slipper-like and lacking tuft of hair …………………………9 9 Leaves paired and +/- opposite in middle of stem. ……………………………….Listera 9 Leaves not paired in middle of stem……………….…………………………………. 11 11 Leaves in a basal rosette, evergreen, often mottled; plants with creeping rhizomes…… ………………………………………………………………………………… Goodyera 11 Leaves along stem; plants lacking creeping rhizomes………………………………. 12 12 Flowers white; inflorescence tightly spiraled; leaves linear-lanceolate……. Spiranthes 12 Flowers greenish to brownish-purple; inflorescence open; leaves lanceolate to ovate …...……………………………………………………………………………. Epipactis James P. Riser II – Idaho/WesternWA Orchid Workshop INPS 7 March 2009 - 2 - Corallorhiza 1 Sepals and petals with prominent reddish-brown stripes; lip lacking spur……. -

Dottorato Di Ricerca

Università degli Studi di Cagliari DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN SCIENZE E TECNOLOGIE DELLA TERRA E DELL'AMBIENTE Ciclo XXXI Patterns of reproductive isolation in Sardinian orchids of the subtribe Orchidinae Settore scientifico disciplinare di afferenza Botanica ambientale e applicata, BIO/03 Presentata da: Dott. Michele Lussu Coordinatore Dottorato Prof. Aldo Muntoni Tutor Dott.ssa Michela Marignani Co-tutor Prof.ssa Annalena Cogoni Dott. Pierluigi Cortis Esame finale anno accademico 2018 – 2019 Tesi discussa nella sessione d’esame Febbraio –Aprile 2019 2 Table of contents Chapter 1 Abstract Riassunto………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Preface ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Chapter 2 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 Aim of the study…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Chapter 3 What we didn‘t know, we know and why is important working on island's orchids. A synopsis of Sardinian studies……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 17 Chapter 4 Ophrys annae and Ophrys chestermanii: an impossible love between two orchid sister species…………. 111 Chapter 5 Does size really matter? A comparative study on floral traits in two different orchid's pollination strategies……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 133 Chapter 6 General conclusions………………………………………………………………………………………... 156 3 Chapter 1 Abstract Orchids are globally well known for their highly specialized mechanisms of pollination as a result of their complex biology. Based on natural selection, mutation and genetic drift, speciation occurs simultaneously in organisms linking them in complexes webs called ecosystems. Clarify what a species is, it is the first step to understand the biology of orchids and start protection actions especially in a fast changing world due to human impact such as habitats fragmentation and climate changes. I use the biological species concept (BSC) to investigate the presence and eventually the strength of mechanisms that limit the gene flow between close related taxa.