A Legal-Empirical Study of the Unauthorized Use of Credit Cards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

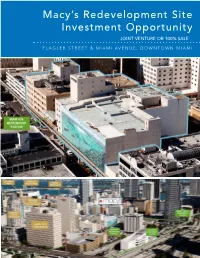

Macy's Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity

Macy’s Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity JOINT VENTURE OR 100% SALE FLAGLER STREET & MIAMI AVENUE, DOWNTOWN MIAMI CLAUDE PEPPER FEDERAL BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 13 CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OVERVIEW 24 MARKET OVERVIEW 42 ZONING AND DEVELOPMENT 57 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO 64 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 68 LEASE ABSTRACT 71 FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: PRIMARY CONTACT: ADDITIONAL CONTACT: JOHN F. BELL MARIANO PEREZ Managing Director Senior Associate [email protected] [email protected] Direct: 305.808.7820 Direct: 305.808.7314 Cell: 305.798.7438 Cell: 305.542.2700 100 SE 2ND STREET, SUITE 3100 MIAMI, FLORIDA 33131 305.961.2223 www.transwestern.com/miami NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITION, WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY LISTING CONDITIONS, IMPOSED BY THE OWNER. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MACY’S SITE MIAMI, FLORIDA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Downtown Miami CBD Redevelopment Opportunity - JV or 100% Sale Residential/Office/Hotel /Retail Development Allowed POTENTIAL FOR UNIT SALES IN EXCESS OF $985 MILLION The Macy’s Site represents 1.79 acres of prime development MACY’S PROJECT land situated on two parcels located at the Main and Main Price Unpriced center of Downtown Miami, the intersection of Flagler Street 22 E. Flagler St. 332,920 SF and Miami Avenue. Macy’s currently has a store on the site, Size encompassing 522,965 square feet of commercial space at 8 W. Flagler St. 189,945 SF 8 West Flagler Street (“West Building”) and 22 East Flagler Total Project 522,865 SF Street (“Store Building”) that are collectively referred to as the 22 E. -

Colors for Bathroom Accessories

DUicau kji oLctnufcirus DEC 6 1937 CS63-38 Colors (for) Bathroom Accessories U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE DANIEL C. ROPER, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS LYMAN J. BRIGGS, Director COLORS FOR BATHROOM ACCESSORIES COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS63-38 Effective Date for New Production, January I, 1938 A RECORDED STANDARD OF THE INDUSTRY UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1S37 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 5 cents U. S. Department of Commerce National Bureau of Standards PROMULGATION of COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS63-38 for COLORS FOR BATHROOM ACCESSORIES On April 30, 1937, at the instance of the National Retail Dry Goods Association, a general conference of representative manufacturers, dis- tributors, and users of bathroom accessories adopted seven commercial standard colors for products in this field. The industry has since ac- cepted and approved for promulgation by the United States Depart- ment of Commerce, through the National Bureau of Standards, the standard as shown herein. The standard is effective for new production from January 1, 1938. Promulgation recommended. I. J. Fairchild, Chief, Division of Trade Standards. Promulgated. Lyman J. Briggs, Director, National Bureau of Standards. Promulgation approved. Daniel C. Roper, Secretary of Commerce. II COLORS FOR BATHROOM ACCESSORIES COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS63-38 PURPOSE 1 . Difficulty in securing a satisfactory color match between articles purchased for use in bathrooms, where color harmony is essential to pleasing appearance, has long been a source of inconvenience to pur- chasers. This difficulty is greatest when items made of different materials are produced by different manufacturers. Not only has this inconvenienced purchasers, but it has been a source of trouble and loss to producers and merchants through slow turnover, multiplicity of stock, excessive returns, and obsolescence. -

Department Stores on Sale: an Antitrust Quandary Mark D

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 1 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary Mark D. Bauer Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark D. Bauer, Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bauer: Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary DEPARTMENT STORES ON SALE: AN ANTITRUST QUANDARY Mark D. BauerBauer*• INTRODUCTION Department stores occupy a unique role in American society. With memories of trips to see Santa Claus, Christmas window displays, holiday parades or Fourth of July fIreworks,fireworks, department storesstores- particularly the old downtown stores-are often more likely to courthouse.' engender civic pride than a city hall building or a courthouse. I Department store companies have traditionally been among the strongest contributors to local civic charities, such as museums or symphonies. In many towns, the department store is the primary downtown activity generator and an important focus of urban renewal plans. The closing of a department store is generally considered a devastating blow to a downtown, or even to a suburban shopping mall. Many people feel connected to and vested in their hometown department store. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

Case3:15-cv-00612-SC Document1 Filed02/09/15 Page1 of 45 1 AMSTER, ROTHSTEIN & EBENSTEIN LLP ANTHONY F. LO CICERO, NY SBN1084698 2 [email protected] CHESTER ROTHSTEIN, NY SBN2382984 3 [email protected] MARC J. JASON, NY SBN2384832 4 [email protected] JESSICA CAPASSO, NY SBN4766283 5 [email protected] 90 Park Avenue 6 New York, NY 10016 Telephone: (212) 336-8000 7 Facsimile: (212) 336-8001 (Pro Hac Vice Applications Forthcoming) 8 HANSON BRIDGETT LLP 9 GARNER K. WENG, SBN191462 [email protected] 10 CHRISTOPHER S. WALTERS, SBN267262 [email protected] 11 425 Market Street, 26th Floor San Francisco, California 94105 12 Telephone: (415) 777-3200 Facsimile: (415) 541-9366 13 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 14 MACY'S, INC. and MACYS.COM, INC. 15 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 16 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 17 SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 18 19 MACY'S, INC. and MACYS.COM, INC., Case No. 20 Plaintiffs, COMPLAINT FOR TRADEMARK 21 INFRINGEMENT, FALSE ADVERTISING, v. FALSE DESIGNATION OF ORIGIN, 22 DILUTION, AND UNFAIR COMPETITION STRATEGIC MARKS, LLC and ELLIA 23 KASSOFF, DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL 24 Defendants. 25 26 27 28 -1- COMPLAINT Case3:15-cv-00612-SC Document1 Filed02/09/15 Page2 of 45 1 Plaintiffs Macy’s, Inc. and Macys.com, Inc. (collectively and individually “Macy’s” or 2 “Plaintiffs”), by their attorneys, for their complaint against Defendants Strategic Marks, 3 LLC (“Strategic Marks”) and Ellia Kassoff (collectively “Defendants”) allege as follows: 4 INTRODUCTION 5 1. Macy’s is commencing this action on an emergent basis to prevent the 6 expansion of Defendants’ willful, intentional and flagrant misappropriation of Macy’s 7 famous trademarks. -

Von Maur Burdines Hess Meier & Frank Wanamaker’S

INVESTOR UPDATE Quality Properties in Compelling Markets M A R C H 2 0 1 7 PREIT’s STRATEGIC VISION Quality continues to be PREIT’s guiding principle to achieve its strategic vision by 2020 24 mall portfolio capable of producing outsized growth led by: Cherry Hill ($658/sf), FOP (proj. >$650/sf), Willow Grove ($632/sf), Springfield TC ($530/sf w/o Apple) $525 psf in sales Powerful presence in 2 Top 10 markets: Philadelphia and Washington DC Over 20% of space committed to dining and entertainment, insulated from shifts in apparel preferences A strong, diversified anchor mix Densification opportunities in major markets A balanced plan that leads to targeted 2018 – 2020 NOI growth of 6-8% and 2020 leverage below 47% 2 OPERATING HIGHLIGHTS Year Ended December 31, 2016 FFO, as adjusted per share growth (1) 16.4% Average Quarterly SS NOI growth 4.4% Average Renewal Spreads YTD (2) 14.3% Sales PSF/growth $464/+7.4% Non-Anchor Mall Occupancy % 93.5% Non-Anchor Mall Leased % 94.4% (1) Excluding dilution from asset sales (2) Excluding leases restructured with Aeropostale following bankruptcy filing 3 ACTION IN THE FACE OF RAPID CHANGE The actions we have taken pave the way for continued quality improvement and strong growth prospects We have demonstrated leadership in the face of a rapidly-changing retail landscape. Our multi-year view validates how our forward-thinking focus on quality and the bold actions we have taken lay the foundation for continuous shareholder value creation. These bold actions include: • our aggressive disposition strategy • early adoption of dining and entertainment uses • the off-market acquisition of Springfield Town Center • reinvention of three city blocks in downtown Philadelphia • our proactive approach to strengthening our anchor mix CYCLE OF IMPROVEMENT More NOI/Lower Better Portfolio Cap Rate Value Sales Growth Creation Better Tenants Improved Shopper Demographics These bold actions, taken together, fortify our portfolio. -

Burdines-Macy's Offers Downtown Miami Store to FIU for Classes

Contractor says airport terminal should not be re-bid Burdines-Macy's offers downtown Week of Feburary 24, 2005 Miami store to FIU for classes Calendar of Events Burdines-Macy's offers downtown Miami Local officials shrug off film magazine's rankings FYI Miami store to FIU for classes Miami, South Florida Workforce still Filming in Miami hoping for jobs program Classified Ads By Tom Harlan Museums awaiting bond funds, Burdines-Macy's is offering space at its landmark downtown Miami store to Miami master plan before working Florida International University. Front Page on move FIU and Burdines-Macy's are working on a deal that would allow the Traffic-clogging Fifth Street Bridge About Miami Today university to start classes in a portion of the Flagler Street store in May, a to be replaced university spokesman said, after space is reconstructed to accommodate the Put Your Message students. Bond payments could force taxes in Miami Today FIU is in talks to open a small center for its MBA program at the company's up in growth slows, analyst says Contact Miami store at 22 E Flagler St. Today Company spokespeople say Nirmal K. "Trip" Tripathy, president and chief operating officer of Federated Department Stores in Miami, suggested that the Job Opportunities store unite with the university. Research Our Files Under the plan, College of Business Administration Dean Jose de la Torre and Assistant Dean Tomislav Mandakovic would manage the center and FIU The Online Archive business management professors would teach a variety of courses. Order Reprints The university offers three MBA degrees: an executive MBA, an evening MBA and an international MBA that U.S. -

Are You Sure You're Not Being Overcharged?

843.576.3638 WWW.ABOUTSIB.COM IT/TELECOM MAINTENANCE WASTE PROPERTY CONTRACTS REMOVAL TAX TREASURY SHIPPING UTILITIES CLASS ACTION RECOVERY BENCHMARK PRICING CONTRACT NEGOTIATION BEST-IN-CLASS / UNPUBLISHED RATES REFUNDS FROM BILLING ERRORS Are you sure you’re not being overcharged? We guarantee 98% of you are. COMPANY OVERVIEW SIB’S MISSION Founded in 2008 98% We use our proven three-pronged method to find savings: Headquartered in Charleston, SC Success Rate 75 employees Benchmark SIB specializes in cost reduction. By employing experts in each of the Analyze billing Standardize service Negotiate 50 STATES & CANADA fields we review, we are uniquely equipped to find savings in virtually Pricing Data From to discover and levels (making sure best-in-class any fixed cost categorywithout changing your current vendors. $3 BILLION ANALYZED correct vendors’ clients are not being pricing billing errors and charged for services We have no upfront fees. SIB bills only on the savings we find, and Over 50,000 only after you realize those savings. If we don’t find savings there is ensure contract they do not use no cost, and you know that your bills are as low as possible. Locations compliance or need) SIB has worked with Fortune 500 companies, restaurant groups, hotel Nationwide groups, regional banks, senior living groups, hospital groups, grocery chains, retail chains, state, local and federal government entities, and everything in between. Since opening in 2008, we’ve found savings for over 98% of our clients. Ongoing Bill SIB makes the process of cost reduction effortless for your company, allowing you to rest easy knowing that industry experts are working hard Monitoring OUR MISSION IS TO SAVE OUR CLIENTS MONEY WITHOUT to reduce your costs. -

Dinkins August 4, 1953 - March 28, 2015

PHONE: (972) 562-2601 Melissa "Missy" Renee Dinkins August 4, 1953 - March 28, 2015 Melissa "Missy" Renee Dinkins of Plano, Texas passed away March 28, 2015 at the age of 61. She was born August 4, 1953 to Robert William Seymour and Juanita Marie in Tampa, Florida. Melissa married Stephen C. Dinkins on September 16, 1978 in Tampa, Florida. She was a women’s apparel buyer for Maas Brothers Department Stores in Tampa, Florida, Burdines Department in Miami, Florida, and Stage Stores in Houston, Texas. Melissa was of the protestant faith. She is survived by her spouse Stephen C. Dinkins of Plano, Texas; daughters, Tracy Lynn Esmond and husband Greg of McKinney, Texas and Amy Kathleen Viau and husband Matthew of Apex, North Carolina; grandchildren, Tiffany Paige Esmond, Lily Marie Viau, and Sophie Kathleen Viau; sister, Nannette Elaine Lorenz and husband Troy Joseph of Tampa, Florida; brother, Robert William Seymour and wife Linda Muriel of Tampa, Florida; and her favorite pet, Molly. Melissa was preceded in death by her parents, Robert and Juanita Seymour; niece, Tiffany Ann Harasiuk;and nephew, Chad Vincent Seymour. Memorials Steve and Family - I am speechless. The times I spent with you and Missy were some of the best. She just had a way of wrapping her arms around everyone. She made sure everyone knew they belonged. And you were clearly her world. She loved you so. It was such a pleasure to see that. Thank you and Missy for all you've done for me. She left this world a better place and is dearly missed. -

Temple Law Review Articles

BAUER_FINAL TEMPLE LAW REVIEW © 2007 TEMPLE UNIVERSITY OF THE COMMONWEALTH SYSTEM OF HIGHER EDUCATION VOL. 80 NO. 4 WINTER 2007 ARTICLES “GIVE THE LADY WHAT SHE WANTS”—AS LONG AS IT IS MACY’S ∗ Mark D. Bauer I. INTRODUCTION Chicago burned to the ground in the Great Fire of 1871.1 But, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, the city was quickly rebuilt, and rebuilt better than before.2 ∗ Associate Dean of Academics and Associate Professor of Law, Stetson University College of Law. A.B., The University of Chicago; J.D., Emory University. The author was formerly an attorney with the Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Competition. This Article was presented as a work in progress at the Southeastern Association of Law Schools’ 2006 annual conference, Indiana University School of Law–Indianapolis, Mercer University School of Law, and the Canadian Law & Economics Association of the University of Toronto. The author thanks Joan Heminway, Linda Jellum, Andy Klein, and Jack Sammons for arranging these talks and providing such helpful feedback. The author also thanks the Stetson University College of Law Library staff: Rebecca Trammel, director of Stetson’s library (who generously allowed her staff to provide so much help on this project and also who traveled to Denver to review newspaper microfilm), Pam Burdett (who coordinated the work of the library staff and traveled to Atlanta to review microfilm), Kristin Fiato, Evelyn Kouns, Janet Peters, Cathy Rentschler, Wanita Scroggs, Julieanne Hartman Stevens, Sally Waters, and Avis Wilcox for their help. The author also gratefully acknowledges student research assistants Marc Levine, Marisa Gonzalez, and Mike Kincart, who did background research, and Dana Dean, who was instrumental in assisting with the collection and analysis of the empirical data in this Article. -

The Rouse Compan Y

CX_Rouse Cover 4/14/99 3:03 PM Page III THE ROUSE COMPAN Y Creating a ortfolio Pof Quality A N N U AL REPORT 1998 CX_Rouse Cover 4/14/99 3:03 PM Page IV Creating a ortfolio Pof Quality HE ROUSE COMPA N Y traces its founding back to 1939 as a mortg a g e Tbanking firm. Since the mid-1950s, the Company’s primary business has been the development and management of commercial real estate proj e c t s , st a r ting out with retail centers and later including new communities and office and industrial projects. Among the Company’s well-known retail projects are Faneuil Hall Marketplace in Boston, South Street Seaport in New York, Harborplace in Bal t i m o r e, The Fashion Sho w in Las Vegas, Beachwood Place in Cleve- land and Perimeter Mall in Atlanta. Well-known, mixed-use projects include Pioneer Place in Portland, Westlake Center in Seattle and Arizona Center in Phoenix. The Company, through its affiliates, is also developer of two of the most successful new communities in the United States: Columbia, Maryland and Summerlin, Nevada. The Company views the development, prop e r ty management and acquisition/disposition efforts as long term value creation opportu n i t i e s . Beginning on page 7, a special section of this rep o r t is devoted to the Com- pa n y ’s overall objectives and some of the developments, acquisitions, dispo- sitions and management strategies that create and enhance the value of this po r tfolio of prop e rt i e s . -

The Wonderful World of the Department Store in Historical Perspective: a Comprehensive International Bibliography, Partially Annotated

The Wonderful World of the Department Store in Historical Perspective: A Comprehensive International Bibliography, Partially Annotated By Robert D. Tamilia PhD Professor of Marketing Department of Marketing École des sciences de la gestion University of Quebec at Montreal [email protected] Revised and updated periodically (Last update: July, 2011) Note : The following short introduction to the department store was first written when this bibliographical project was initiated by the author in 2000. Since then, the introduction has been updated but is still incomplete. Over the past 10 years, new information sources on the department store have been found which makes it near impossible to summarize in this introduction the history of this retail institution which evolved over time along with the history of retailing. The wealth of information on the department store over the past 150 years is quite impressive especially since the 1970s when historical research in the social sciences became increasing popular among historians of all stripes but less so in academic marketing. A more complete introduction to the wonderful world of department store can be found in Tamilia (2003) and Tamilia and Reid (2007) . Abstract The paper has two main objectives. The first is to provide a short summary of what the department store is all about. There is a need to discuss its historical role not only in marketing and retailing, but also in society and the world in general. The next objective is to provide social historians and other historical researchers with the most comprehensive and complete reference list on the department store ever compiled. -

Colors for Kitchen Accessories

Bureau of Standards DEC 6 1937 CS62-38 Colors; (for) Kitchen Accessories U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE DANIEL C. ROPER, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS LYMAN J. BRIGGS, Director COLORS FOR KITCHEN ACCESSORIES COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS62-38 Effective Dale for New Fr@<l3K6©Bi, January 1, 1938 A RECORDED STANDARD OF THE INDUSTRY ONETEB STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON j 1937 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D, C. Price 5 cents 'U. S. Department of Commerce National Bureau of Standards PROMULGATION of COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS62-38 for COLORS FOR KITCHEN ACCESSORIES ‘ On April 30, 1937, at the instance of the National Retail Dry Goods Association, a general conference of representative manufacturers, ^ distributors, and users of kitchen accessories adopted six commercial | standard colors for products in this field. The industry has since | accepted and approved for promulgation by the United States De- j partment of Commerce, through the National Bureau of Standards, the standard as shown herein. The standard is effective for new production from January 1, 1938. Promulgation recommended. I. J. Fairchild, Chief, Division of Trade Standards, Promulgated. Lyman J. Briggs, Director, National Bureau of Standards. Promulgation approved. Daniel C. Roper, Secretary of Commerce, II COLORS FOR KITCHEN ACCESSORIES COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS62-38 PURPOSE 1. Difficulty in securing a satisfactory color match between articles purchased for use in kitchens, where color harmony is essential to pleasing appearance, has long been a source of inconvenience to pur- chasers. This difficulty is greatest when items made of different materials are produced by different manufacturers. Not only has this inconvenienced purchasers but it has been a source of trouble and loss to producers and merchants through slow turnover, multi- phcity of stock, excessive returns, and obsolescence.