The Wonderful World of the Department Store in Historical Perspective: a Comprehensive International Bibliography, Partially Annotated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHEL Holdings Europe Limited ANNUAL REPORT AND

SHEL Holdings Europe Limited ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS For the period ended 28 January 2017 Pag© CONTENDS Strategic report Directors' report 5 Statement of directors' responsibilities 6 Independent auditors' report to the members of SHEL Holdings Europe Limited g Consolidated income statement and other comprehensive income 10 Consolidated balance sheet 12 Consolidated statement of changes In equity 13 Consolidated cash flow statement 14 Notes to the financial statements 51 Company balance sheet 52 Company statement of changes in equity 53 Company cash flow statement 54 Notes to the company financial statements COMPANY SECRETARY AND REGISTERED OFFICE S Hemsley, 400 Oxford Street, London \A/1 A1AB INDEPENDENT AUDITORS PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, Chartered Accountants and Statutory Auditors, The Atrium, 1 Harefield Road, Oxbridge, UBB1EX COMPANY'S REGISTERED NUMBER The Company's registered number is 07826605. SHEL Holdings Europe Limited Strategic report for the period ended 28 January 2017 The directors present their strategic report and the audited financial statements of the Company and the Group for the period ended 28 January 2017. Review of the business Principal activities The principal activity of the Company is as a holding Company for Group activities which are department store arid online retailing. Results The financial statements reflect the results of SHEL Holdings Europe Limited and Its subsidiary undertakings. Turnover for the 52 weeks to 28 January 2017 was £1,205.7 million (52 weeks ended 30 January 2016; £1,032.8 million). Group profit on ordinary activities before taxation was £105.2 million (2016: £81.1 million). The profit after taxation for the financial period of £78.5 million (2016: £64.3 million) has been transferred to reserves. -

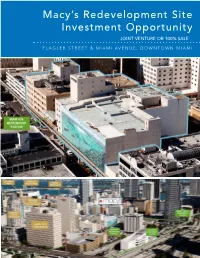

Macy's Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity

Macy’s Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity JOINT VENTURE OR 100% SALE FLAGLER STREET & MIAMI AVENUE, DOWNTOWN MIAMI CLAUDE PEPPER FEDERAL BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 13 CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OVERVIEW 24 MARKET OVERVIEW 42 ZONING AND DEVELOPMENT 57 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO 64 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 68 LEASE ABSTRACT 71 FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: PRIMARY CONTACT: ADDITIONAL CONTACT: JOHN F. BELL MARIANO PEREZ Managing Director Senior Associate [email protected] [email protected] Direct: 305.808.7820 Direct: 305.808.7314 Cell: 305.798.7438 Cell: 305.542.2700 100 SE 2ND STREET, SUITE 3100 MIAMI, FLORIDA 33131 305.961.2223 www.transwestern.com/miami NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITION, WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY LISTING CONDITIONS, IMPOSED BY THE OWNER. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MACY’S SITE MIAMI, FLORIDA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Downtown Miami CBD Redevelopment Opportunity - JV or 100% Sale Residential/Office/Hotel /Retail Development Allowed POTENTIAL FOR UNIT SALES IN EXCESS OF $985 MILLION The Macy’s Site represents 1.79 acres of prime development MACY’S PROJECT land situated on two parcels located at the Main and Main Price Unpriced center of Downtown Miami, the intersection of Flagler Street 22 E. Flagler St. 332,920 SF and Miami Avenue. Macy’s currently has a store on the site, Size encompassing 522,965 square feet of commercial space at 8 W. Flagler St. 189,945 SF 8 West Flagler Street (“West Building”) and 22 East Flagler Total Project 522,865 SF Street (“Store Building”) that are collectively referred to as the 22 E. -

The Coinage of Akragas C

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Numismatica Upsaliensia 6:1 STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA 6:1 The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC Text and Plates ULLA WESTERMARK I STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA Editors: Harald Nilsson, Hendrik Mäkeler and Ragnar Hedlund 1. Uppsala University Coin Cabinet. Anglo-Saxon and later British Coins. By Elsa Lindberger. 2006. 2. Münzkabinett der Universität Uppsala. Deutsche Münzen der Wikingerzeit sowie des hohen und späten Mittelalters. By Peter Berghaus and Hendrik Mäkeler. 2006. 3. Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. Svenska vikingatida och medeltida mynt präglade på fastlandet. By Jonas Rundberg and Kjell Holmberg. 2008. 4. Opus mixtum. Uppsatser kring Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. 2009. 5. ”…achieved nothing worthy of memory”. Coinage and authority in the Roman empire c. AD 260–295. By Ragnar Hedlund. 2008. 6:1–2. The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC. By Ulla Westermark. 2018 7. Musik på medaljer, mynt och jetonger i Nils Uno Fornanders samling. By Eva Wiséhn. 2015. 8. Erik Wallers samling av medicinhistoriska medaljer. By Harald Nilsson. 2013. © Ulla Westermark, 2018 Database right Uppsala University ISSN 1652-7232 ISBN 978-91-513-0269-0 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876 (http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876) Typeset in Times New Roman by Elin Klingstedt and Magnus Wijk, Uppsala Printed in Sweden on acid-free paper by DanagårdLiTHO AB, Ödeshög 2018 Distributor: Uppsala University Library, Box 510, SE-751 20 Uppsala www.uu.se, [email protected] The publication of this volume has been assisted by generous grants from Uppsala University, Uppsala Sven Svenssons stiftelse för numismatik, Stockholm Gunnar Ekströms stiftelse för numismatisk forskning, Stockholm Faith and Fred Sandstrom, Haverford, PA, USA CONTENTS FOREWORDS ......................................................................................... -

Orcadians (And Some Shetlanders) Who Worked West of the Rockies in the Fur Trade up to 1858 (Unedited Biographies in Progress)

Orcadians (and some Shetlanders) who worked west of the Rockies in the fur trade up to 1858 (unedited biographies in progress) As compiled by: Bruce M. Watson 208-1948 Beach Avenue Vancouver, B. C. Canada, V6G 1Z2 As of: March, 1998 Information to be shared with Family History Society of Orkney. Corrections, additions, etc., to be returned to Bruce M. Watson. A complete set of biographies to remain in Orkney with Society. George Aitken [variation: Aiken ] (c.1815-?) [sett-Willamette] HBC employee, British: Orcadian Scot, b. c. August 20, 1815 in "Greenay", Birsay, Orkney, North Britain [U.K.] to Alexander (?-?) and Margaret [Johnston] Aiken (?-?), d. (date and place not traced), associated with: Fort Vancouver general charges (l84l-42) blacksmith Fort Stikine (l842-43) blacksmith steamer Beaver (l843-44) blacksmith Fort Vancouver (l844-45) blacksmith Fort Vancouver Depot (l845-49) blacksmith Columbia (l849-50) Columbia (l850-52) freeman Twenty one year old Orcadian blacksmith, George Aiken, signed on with the Hudson's Bay Company February 27, l836 and sailed to York Factory where he spent outfits 1837-40; he then moved to and worked at Norway House in 1840-41 before being assigned to the Columbia District in 1841. Aiken worked quietly and competently in the Columbia district mainly at coastal forts and on the steamer Beaver as a blacksmith until March 1, 1849 at which point he went to California, most certainly to participate in the Gold Rush. He appears to have returned to settle in the Willamette Valley and had an association with the HBC until 1852. Aiken's family life or subsequent activities have not been traced. -

Colors for Bathroom Accessories

DUicau kji oLctnufcirus DEC 6 1937 CS63-38 Colors (for) Bathroom Accessories U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE DANIEL C. ROPER, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS LYMAN J. BRIGGS, Director COLORS FOR BATHROOM ACCESSORIES COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS63-38 Effective Date for New Production, January I, 1938 A RECORDED STANDARD OF THE INDUSTRY UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1S37 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 5 cents U. S. Department of Commerce National Bureau of Standards PROMULGATION of COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS63-38 for COLORS FOR BATHROOM ACCESSORIES On April 30, 1937, at the instance of the National Retail Dry Goods Association, a general conference of representative manufacturers, dis- tributors, and users of bathroom accessories adopted seven commercial standard colors for products in this field. The industry has since ac- cepted and approved for promulgation by the United States Depart- ment of Commerce, through the National Bureau of Standards, the standard as shown herein. The standard is effective for new production from January 1, 1938. Promulgation recommended. I. J. Fairchild, Chief, Division of Trade Standards. Promulgated. Lyman J. Briggs, Director, National Bureau of Standards. Promulgation approved. Daniel C. Roper, Secretary of Commerce. II COLORS FOR BATHROOM ACCESSORIES COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS63-38 PURPOSE 1 . Difficulty in securing a satisfactory color match between articles purchased for use in bathrooms, where color harmony is essential to pleasing appearance, has long been a source of inconvenience to pur- chasers. This difficulty is greatest when items made of different materials are produced by different manufacturers. Not only has this inconvenienced purchasers, but it has been a source of trouble and loss to producers and merchants through slow turnover, multiplicity of stock, excessive returns, and obsolescence. -

Dan Ryan Lessons Learnt and Still Learning from a Life in Retail Life Who Am I? a Retailer from Cork Loud Laugh Retail

Dan Ryan Lessons learnt and still learning from a life in retail Life Who am I? A Retailer From Cork Loud Laugh Retail My3 Journey Retail My experience . Retailer Manager . Retail Buyer . Retail Merchandiser . Trading Director . Head of Commercial Trading Experience Domestic & International . Ireland . UK . Spain . Netherlands . Canada 5 Penneys/Primark 1985 -1999 Trainee Merchandise Manager Controller How did that happen? Brown Thomas 1999 - 2006 Merchandise Controller From ridiculous prices at Primark To sublime prices at BT From private label at Primark To Global Brands at BT Penneys/Primark 2006 - 2008 Re-joined as Director of Merchandising Why go back? Primark comes to Spain Expanding into new markets . The budget fashion chain opened it’s first store outside the UK & Ireland . 1st store in a new shopping centre in Madrid 2006 . Primark executives say they chose Spain as the launching point for a European expansion because Spanish consumer patterns are similar to those of Ireland. 5/23/2019 ADD A FOOTER Lifestyle Sports 2008 - 2012 Appointed to the Board as Trading Director SPORTS RETAIL Fantastic Combination - love Sports & love Retail 2008 Financial Crash What do we do? . Devised 5 Year Strategy . Restructured Buying and Merchandising Team . What categories are we going to be famous for? . Closed loss making stores/opened new stores . Refurbished existing stores Shop Direct Group, Liverpool 2012 - 2013 From Bricks to Clicks Shop Direct Group . A merger of once bitter rivals Littlewoods and Great Universal Stores . Based in Liverpool . Legacy of home catalogue shopping . Restructured . Now trading online only : Littlewoods , Very 5/23/2019 ADD A FOOTER Selfridges Group 2013 - 2019 Renewing old acquaintances Pastures New – The Netherlands & Canada de Bijenkorf More change . -

Will Connell Papers LSC.0893

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5199n9r9 Online items available Finding Aid for the Will Connell papers LSC.0893 Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2020 July 30. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Will Connell LSC.0893 1 papers LSC.0893 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Will Connell papers Creator: Connell, Will Identifier/Call Number: LSC.0893 Physical Description: 76 Linear Feet(152 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1928-1961 Abstract: Will Connell (1898-1961) was a self-taught photographer. He opened a studio in downtown Los Angeles in 1925 and became a member of the Camera Pictorialists. He taught at Art Center College in Pasadena from 1931 until his death. His work included movie publicity shots, magazine assignments and other commercial photography. The collection consists of photographs, negatives, experimental work, correspondence, instructional materials, and ephemera. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements PORTIONS OF THIS COLLECTION HAVE BEEN DIGITIZED. Please consult digital facsimiles instead of originals. Conditions Governing Use Property rights to the physical objects belong to UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Dudok, WM (Willem Marinus)

Nummer Toegang: DUDO Dudok, W.M. (Willem Marinus) / Archief Het Nieuwe Instituut (c) 2000 This finding aid is written in Dutch. 2 Dudok, W.M. (Willem Marinus) / Archief DUDO DUDO Dudok, W.M. (Willem Marinus) / Archief 3 INHOUDSOPGAVE BESCHRIJVING VAN HET ARCHIEF......................................................................5 Aanwijzingen voor de gebruiker.......................................................................6 Citeerinstructie............................................................................................6 Openbaarheidsbeperkingen.........................................................................6 Archiefvorming.................................................................................................7 De verwerving van het archief.....................................................................7 Geschiedenis van de archiefvormer.............................................................8 Dudok, Willem Marinus.............................................................................8 Manier van ordenen.........................................................................................9 BESCHRIJVING VAN DE SERIES EN ARCHIEFBESTANDDELEN........................................13 DUDO.110337940 Correspondentie...............................................................13 DUDO.110280905 Correspondentiereeks 1925-1968...........................................13 DUDO.110338067 Correspondentie uit de aanwinst van de Dudok Stichting 1925- 1989.................................................................................................................... -

The Fur Trade Era, 1770S–1849

Great Bear Rainforest The Fur Trade Era, 1770s–1849 The Fur Trade Era, 1770s–1849 The lives of First Nations people were irrevocably changed from the time the first European visitors came to their shores. The arrival of Captain Cook heralded the era of the fur trade and the first wave of newcomers into the future British Columbia who came from two directions in search of lucrative pelts. First came the sailors by ship across the Pacific Ocean in pursuit of sea otter, then soon after came the fort builders who crossed the continent from the east by canoe. These traders initiated an intense period of interaction between First Nations and European newcomers, lasting from the 1780s to the formation of the colony of Vancouver Island in 1849, when the business of trade was the main concern of both parties. During this era, the newcomers depended on First Nations communities not only for furs, but also for services such as guiding, carrying mail, and most importantly, supplying much of the food they required for daily survival. First Nations communities incorporated the newcomers into the fabric of their lives, utilizing the new trade goods in ways which enhanced their societies, such as using iron to replace stone axes and guns to augment the bow and arrow. These enhancements, however, came at a terrible cost, for while the fur traders brought iron and guns, they also brought unknown diseases which resulted in massive depopulation of First Nations communities. European Expansion The northwest region of North America was one of the last areas of the globe to feel the advance of European colonialism. -

Coin Strategy

CASE HISTORY COIN 1 COIN: one hundred years of history • 1916 Vittorio Coin starts the Gruppo Coin activities • 1926 First Coin Store (Mirano, Venice) • 1965 Coin P.za 5 Giornate opens (Milan) • 1972 First “Organizzazione Vendite Speciali” (Oviesse) store • 1986 Coin is the first retailer to develop a fidelity card program in Italy • 1995 Oviesse become an apparel retailer • 1998 Acquisition of La Standa • 1999 Listing of Gruppo Coin on the Milan Stock Exchange • 2005 PAI equity fund becomes Gruppo Coin majority shareholder • 2008 Acquisition of Melablu • 2010 Acquisition of UPIM • 2011 BC Partners becomes Gruppo Coin majority shareholder • 2011 Excelsior opens in Milan • 2012 Acquisition of IANA • 2013 Excelsior opens in Verona • 2014 Coin Excelsior opens in Rome 2 Coin in a snapshot Established in 1926, Coin is the largest Italian department store €413,2 m net sales in 2014 77 stores in Italy and 20 abroad, located downtown in the most important Italian cities and shopping areas Portfolio of 800 brands 46 million visitors every year 21,6 million items sold and 12 million receipts 3 Where we come from: Net Sales and Sqm building 2008–2010–2012 TOTAL CATEGORY (Beauty and Home not included) ● NET SALES 2008 2010 2012 11% 35% 33% hb 41% 50% 32% ws 57% concession 17% 24% NET SALES (€/1000): 232.935 NET SALES (€/1000): 273.814 NET SALES (€/1000): 276.158 ● SQM BUILDING 2008 2010 2012 8% 26% 35% hb 31% 43% ws 48% concession 61% 26% 22% SQM: 74.100 SQM: 82.010 SQM: 91.335 4 Where we come from: Trend 2007-2011 Ebitda trend (2007 – 2011 ) is positive -

A Guide to Historic Santa Monica City Hall

A G U I D E T O Historic Santa Monica City Hall The city seal, measuring 79 inches in diameter, was created with the same “Petrachrome” method and a palette of colors, textures and elements similar to those used in the Macdonald-Wright murals. Encircled by the words, “City of Santa Monica, California. Founded 1875,” the seal features a mermaid and Spanish galleon on the bay, with sun, mountains, clouds and airplanes behind. A ribbon near the base of the seal carries the city’s motto, Populus Felix en Urbe Felice, translated from the Latin as “Fortunate People in a Fortunate Land.” The seal is inlaid in the center of the foyer floor, surrounded by color tiles that run along the east-west axis of the foyer and halls. A serrated pattern of yellow triangles running against a brown field, bordered by black stripes, echoes the chevron pattern on the tiled wainscoting found nearby. T he Overview With a nautical quality befitting its seaside locale, Santa Monica City Hall reflects the character of its surroundings, making it a civic building truly connected to its constituency. Designed by two prominent Los Angeles architects, it is rec- ognized as an outstanding example of the Public Works Administration (PWA) Moderne style of architecture popularized by Depression-era architects. With original Gladding, McBean ceramic tiles found around the west entrance doorway and throughout the building, and historic Stanton Macdonald-Wright murals in the entry foyer that document the city’s and the state’s history, the building’s architecture has earned it a place in the California Register of Historical Resources (1996), designation as a city landmark and eligibility for listing in the federal Register of Historic Places. -

COVID 19 - Store Opening Status at IGDS Department Stores in the World by Company 8 January 2021

COVID 19 - Store Opening Status at IGDS Department Stores in the World by Company 8 January 2021 IGDS Department Stores Country Stores Status Planned reopening date Comments Al Tayer UAE open n/a Attica Greece closed 11 January Balian Group China open n/a Blue Salon Qatar open n/a Boyner Turkey open n/a Brown Thomas Arnotts Ireland closed 31 January Central Thailand open n/a Opening restrictions on certain days depending on Coin Italy open n/a regions for non food and cosmetics departments. David Jones Australia open n/a De Bijenkorf The Netherlands closed 19 January will be closed as of 10 Ermes Cyprus 31 January January FEDS Taiwan open n/a Galeria Karstadt Kaufhof Germany closed 31 January Stores have to close at 7pm. No opening on Sunday, Globus Switzerland open n/a as planned during the festive season GUM Russia open n/a Department stores closed in Ontario at least until 23 Holt Renfrew Canada some stores are closed n/a January and in Quebec until 8 February J Ballantyne New Zealand open n/a J.Front Retailing Japan open n/a Jamilco Russia open n/a Stores have to close at 7pm. No opening on Sunday, Jelmoli Switzerland open n/a as planned during the festive season Kastner & Öhler Austria closed 24 January Kaubamaja Estonia open n/a 1/2 COVID 19 - Store Opening Status at IGDS Department Stores in the World by Company 8 January 2021 IGDS Department Stores Country Stores Status Planned reopening date Comments KL Sogo Malaysia open n/a Le Bon Marché Rive Gauche France open n/a In-house restaurants and cafés are closed.