High End Department Stores, Their Access to and Use of Diverse Labor Markets: Technical Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

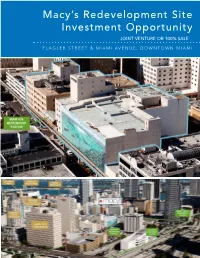

Macy's Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity

Macy’s Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity JOINT VENTURE OR 100% SALE FLAGLER STREET & MIAMI AVENUE, DOWNTOWN MIAMI CLAUDE PEPPER FEDERAL BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 13 CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OVERVIEW 24 MARKET OVERVIEW 42 ZONING AND DEVELOPMENT 57 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO 64 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 68 LEASE ABSTRACT 71 FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: PRIMARY CONTACT: ADDITIONAL CONTACT: JOHN F. BELL MARIANO PEREZ Managing Director Senior Associate [email protected] [email protected] Direct: 305.808.7820 Direct: 305.808.7314 Cell: 305.798.7438 Cell: 305.542.2700 100 SE 2ND STREET, SUITE 3100 MIAMI, FLORIDA 33131 305.961.2223 www.transwestern.com/miami NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITION, WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY LISTING CONDITIONS, IMPOSED BY THE OWNER. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MACY’S SITE MIAMI, FLORIDA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Downtown Miami CBD Redevelopment Opportunity - JV or 100% Sale Residential/Office/Hotel /Retail Development Allowed POTENTIAL FOR UNIT SALES IN EXCESS OF $985 MILLION The Macy’s Site represents 1.79 acres of prime development MACY’S PROJECT land situated on two parcels located at the Main and Main Price Unpriced center of Downtown Miami, the intersection of Flagler Street 22 E. Flagler St. 332,920 SF and Miami Avenue. Macy’s currently has a store on the site, Size encompassing 522,965 square feet of commercial space at 8 W. Flagler St. 189,945 SF 8 West Flagler Street (“West Building”) and 22 East Flagler Total Project 522,865 SF Street (“Store Building”) that are collectively referred to as the 22 E. -

Delightful Holiday Dinner Ideas for the Apocalypse

November 27, 2017 Hearty Tortilla Soup Delightful Holiday Dinner Ideas For the Apocalypse Survivalist foods go mainstream p40 Savory Roasted Beef Teriyaki Style Chicken November 27, 2017 3 PHOTOGRAPH BY IKE EDEANI FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK BLOOMBERG EDEANI FOR IKE BY PHOTOGRAPH 36 Richard Plepler, chief executive officer of HBO CONTENTS Bloomberg Businessweek November 27, 2017 IN BRIEF 8 ○ Uber belatedly discloses a data hack ○ Janet Yellen says so long ○ This year, give thanks for cheaper turkey REMARKS VIEW 12 Finish college in three 10 One fix for fake news: Bring radical years—not four—and start transparency to Facebook and Google your career with a whole lot less debt 1 BUSINESS2 TECHNOLOGY 3 FINANCE 14 The songwriters 19 VIPKid’s virtual 24 Would you trust who want to stop classrooms may a stock call that the music run afoul of real-life came from a robot? labor laws 15 For Asians, “Made in Asia” 26 In the event of nuclear has new appeal war, two things will survive: 20 Google struggles to Cockroaches and bitcoin machete through the lies 4 17 Selling Europe’s soccer in its search results fans American-style sports 27 Venezuela’s oil bonds memorabilia might not be a bargain 22 Man vs. Machine: QuickSee isn’t after your optometrist’s job—yet 4 ECONOMICS 5 POLITICS 28 A Chinese drone 32 “Merkel was 32 Angela Merkel’s maker is taking a historical coalition teeters transportation into figure as far 33 Cutting the health-care Jetsons territory as Europe’s mandate to cut taxes: concerned, Deft maneuver or daft 30 How mobile homes got -

Colors for Bathroom Accessories

DUicau kji oLctnufcirus DEC 6 1937 CS63-38 Colors (for) Bathroom Accessories U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE DANIEL C. ROPER, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS LYMAN J. BRIGGS, Director COLORS FOR BATHROOM ACCESSORIES COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS63-38 Effective Date for New Production, January I, 1938 A RECORDED STANDARD OF THE INDUSTRY UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1S37 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 5 cents U. S. Department of Commerce National Bureau of Standards PROMULGATION of COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS63-38 for COLORS FOR BATHROOM ACCESSORIES On April 30, 1937, at the instance of the National Retail Dry Goods Association, a general conference of representative manufacturers, dis- tributors, and users of bathroom accessories adopted seven commercial standard colors for products in this field. The industry has since ac- cepted and approved for promulgation by the United States Depart- ment of Commerce, through the National Bureau of Standards, the standard as shown herein. The standard is effective for new production from January 1, 1938. Promulgation recommended. I. J. Fairchild, Chief, Division of Trade Standards. Promulgated. Lyman J. Briggs, Director, National Bureau of Standards. Promulgation approved. Daniel C. Roper, Secretary of Commerce. II COLORS FOR BATHROOM ACCESSORIES COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS63-38 PURPOSE 1 . Difficulty in securing a satisfactory color match between articles purchased for use in bathrooms, where color harmony is essential to pleasing appearance, has long been a source of inconvenience to pur- chasers. This difficulty is greatest when items made of different materials are produced by different manufacturers. Not only has this inconvenienced purchasers, but it has been a source of trouble and loss to producers and merchants through slow turnover, multiplicity of stock, excessive returns, and obsolescence. -

Expectations of Store Personnel Managers - Regarding Appropriate Dress for Female Retail Buyers

EXPECTATIONS OF STORE PERSONNEL MANAGERS - REGARDING APPROPRIATE DRESS FOR FEMALE RETAIL BUYERS By JANA KAY GOULD It Bachelor of Science in Home Economics Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1978 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE July, 1981 .. ' ' ' ·~ . ' ' ; EXPECTATIONS OF STORE PERSONNEL MANAGERS REGARDING APPROPRIATE DRESS FOR FEMALE RETAIL BUYERS Thesis Approved: Dean of Graduate College ii 1089'731 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express sincere appreciation to Dr. Grovalynn Sisler, Head, Department of Clothing, Textiles and Merchandising, for her encouragement, assistance and support during the course of this study and in preparation of this thesis. Appreciation is also ex tended to Dr. Janice Briggs and Dr. Elaine Jorgenson for their support and guidance during this study and in the preparation of this manu script. A very grateful acknowledgment is extended to Dr. William Warde for his valuable assistance in the computer analysis of the data and to Mrs. Mary Lou Whee.ler for typing the final manuscript. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 Purpose and Objectives 2 Hypotheses . 3 Assumptions and Limitations 3 Definition of Terms . 4 I I. REV I EH OF LITERATURE . 5 Influence of Clothing on First Impressions 5 Women in the Work Force . • • • 7 Clothing as a Factor in Career Success 9 Characteristics of Fashion Leaders 10 Summary • . • . 12 III. RESEARCH PROCEDURES 13 Type of Research Design ..•.••• 13 Development of the Instrument • 14 Population for the Study 14 Method of Data Analysis • 15 IV. -

A Legal-Empirical Study of the Unauthorized Use of Credit Cards

University of Miami Law Review Volume 21 Number 4 Article 5 7-1-1967 A Legal-empirical Study of the Unauthorized Use of Credit Cards Daniel E. Murray Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Recommended Citation Daniel E. Murray, A Legal-empirical Study of the Unauthorized Use of Credit Cards, 21 U. Miami L. Rev. 811 (1967) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol21/iss4/5 This Leading Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A LEGAL-EMPIRICAL STUDY OF THE UNAUTHORIZED USE OF CREDIT CARDS DANIEL E. MURRAY* I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 811 II. THE CREDIT CARD IN THE COURTS .......................................... 814 A. The Two-Party Credit Arrangement .................................... 814 B. The Three-Party Credit Card Arrangement ............................. 817 III. EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION ................................................. 824 A. Two-Party Credit Card Arrangements .................................. 825 1. THE DEPARTMENT STORE ............................................ 825 B. Three-Party Credit Card Arrangements ................................ 827 1. THE OIL COMPANIES ............................................... -

Department Stores on Sale: an Antitrust Quandary Mark D

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 1 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary Mark D. Bauer Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark D. Bauer, Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bauer: Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary DEPARTMENT STORES ON SALE: AN ANTITRUST QUANDARY Mark D. BauerBauer*• INTRODUCTION Department stores occupy a unique role in American society. With memories of trips to see Santa Claus, Christmas window displays, holiday parades or Fourth of July fIreworks,fireworks, department storesstores- particularly the old downtown stores-are often more likely to courthouse.' engender civic pride than a city hall building or a courthouse. I Department store companies have traditionally been among the strongest contributors to local civic charities, such as museums or symphonies. In many towns, the department store is the primary downtown activity generator and an important focus of urban renewal plans. The closing of a department store is generally considered a devastating blow to a downtown, or even to a suburban shopping mall. Many people feel connected to and vested in their hometown department store. -

The Bon-Ton Stores, Inc. Announces Locations of Store Closures As Part of Store Rationalization Program

The Bon-Ton Stores, Inc. Announces Locations of Store Closures as Part of Store Rationalization Program January 31, 2018 MILWAUKEE, Jan. 31, 2018 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- The Bon-Ton Stores, Inc. (OTCQX:BONT) ("the Company"), today announced the 42 locations that will be closed as part of its previously communicated store rationalization program. The closing stores will include locations under all of the Company's nameplates. "As part of the comprehensive turnaround plan we announced in November, we are taking the next steps in our efforts to move forward with a more productive store footprint," said Bill Tracy, president and chief executive officer for The Bon-Ton Stores. "Including other recently announced store closures, we expect to close a total of 47 stores in early 2018. We remain focused on executing our key initiatives to drive improved performance in an effort to strengthen our capital structure to support the business going forward." Mr. Tracy continued, "We would like to thank the loyal customers who have shopped at these locations and express deep gratitude to our team of hard-working associates for their commitment to Bon-Ton and to serving our customers." In order to ensure a seamless experience for customers, Bon-Ton has partnered with a third-party liquidator, Hilco Merchant Resources, to help manage the store closing sales. The store closing sales are scheduled to begin on February 1, 2018 and run for approximately 10 to 12 weeks. Associates at these locations will be offered the opportunity to interview for available positions at other store locations. The closing locations announced today are in addition to five other recently announced store closures, four of which the Company completed at the end of January and one at which the Company will conclude its closing sale in February. -

A Historical Bibliography of Commercial Architecture in the United States

A HISTORICAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF COMMERCIAL ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES Compiled by Richard Longstreth, 2002; last revised 7 May 2019 I have focused on historical accounts giving substantive coverage of the commercial building types that traditionally distinguish city and town centers, outlying business districts, and roadside development. These types include financial institutions, hotels and motels, office buildings, restaurants, retail and wholesale facilities, and theaters. Buildings devoted primarily to manufacturing and other forms of production, transportation, and storage are not included. Citations of writings devoted to the work of an architect or firm and to the buildings of a community are limited to a few of the most important relative to this topic. For purposes of convenience, listings are divided into the following categories: Banks; Hotels-Motels; Office Buildings; Restaurants; Taverns, etc.; Retail and Wholesale Buildings; Roadside Buildings, Miscellaneous; Theaters; Architecture and Place; Urbanism; Architects; Materials-Technology; and Miscellaneous. Most accounts are scholarly in nature, but I have included some popular accounts that are particularly rich in the historical material presented. Any additions or corrections are welcome and will be included in updated editions of this bibliography. Please send them to me at [email protected]. B A N K S Andrew, Deborah, "Bank Buildings in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia," in William Cutler, III, and Howard Gillette, eds., The Divided Metropolis: Social and Spatial Dimensions -

Goodwill Court Off the Air?

FEBRUARY A MACFADDEN PUBLICATION THE LAWYERS DRIVE GOODWILL COURT OFF THE AIR? COMPLETE WORDS Answering All AND MUSIC TO A Your Questions FAMOUS THEME About SONG IN THIS ISSUE TELEVISION De e tf* etit YES, IF YOUR MAKE -UP'S NATURAL WHAT IS BEAUTY FOR -if All over the world smartly-groomed incredible, astounding effect is that not to set masculine hearts women say Princess Pat rouge is their of color coming from within the skin, favorite. Let's discover its secret of just like a natural blush. You'll be a athrob -if not to bring the thrill utterly natural color. Your rouge-unless glamorous person with Princess Pat of conquests -if not to sing it is Princess Pat -most likely is one flat rouge -irresistible. Try it -and see. little songs of happiness in tone. But Princess Pat rouge is duo -tone. your heart when he admires? There's an under- Make -up's so important - tone that blends especially your rouge! with an overtone, to change magically There's nothing beautiful about on your skin. It be- rouge that looks painted, that outlines comes richly beauti- - itself as a splotch. But Princess Pat ful, vital, real -no r - ------r---- rouge- duo -lone -Ah, there is beauty! outline. The almost PRINCESS PAT, Dept. 792 FREE 2709 South Wells Street, Chicago w Without cost or obligation please send me a Princess Pat cosmetics «r. s are non -allergic! free sample of Princess Pat rouge, as checked English Tint Poppy Gold Squaw Vivid Tan Medium Theatre Nile PRINCESS PAT ROUGE One sample free; additional samples lOc each. -

Lights, Camera, Action NEW YORK — the World, It Seems, Is a Stage for Fragrance Launches from Entertainers

JONES NET FALLS 29.4%/2 LEE’S GUCCI AGENDA/14 Women’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • July 29, 2005 • $2.00 ▲ Carmen Electra is Max WWDFRIDAY Factor’s new U.S. face. Beauty Lights, Camera, Action NEW YORK — The world, it seems, is a stage for fragrance launches from entertainers. The latest are True Star Gold from Tommy Hilfiger, which is being fronted by Beyoncé Knowles, and Fusion, a scent produced by AMC Cosmetics that will be introduced in a story line on the long-running ABC soap “All My Children.” True Star Gold launches in December, while Fusion will make its debut in October. For more, see pages 7 and 10. Federated’s Game Plan: Macy’s to Add 330 Units, Future of L&T Undecided By David Moin NEW YORK — Macy’s will balloon next year to 730 units that will occupy almost every major U.S. market. Federated Department Stores Inc., owner of Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s, disclosed a game plan Thursday for its $17 billion merger with May Department Stores Co. that calls for the giant retailer to convert 330 May stores to Macy’s nameplates in fall 2006. The fates of two of May’s best-known divisions, Lord & Taylor and Marshall Y JOHN SCIULLI/WIREIMAGE Field’s, haven’t been decided, but Lord & Taylor will not be converted to Macy’s, See Macy’s, Page18 Y BRYN KENNY; ELECTRA PHOTO B ELECTRA Y BRYN KENNY; PHOTO BY JOHN AQUINO; STYLED B PHOTO BY 2 WWD, FRIDAY, JULY 29, 2005 WWD.COM Jones Profits Drop 29.4% By Vicki M. -

Piper Jaffray Consumer M&A Weekly

Piper Jaffray Consumer M&A Weekly June 14, 2004 Consumer Mergers & Acquisitions David Jacquin - Managing Director, Group Head, 415-277-1505, [email protected] Scott LaRue - Managing Director, 650-838-1407, [email protected] Tom Halverson - Principal, 612-303-6371, [email protected] John Twichell - Vice President 415-277-1533, [email protected] John Barrymore - Vice President, 415-277-1501, [email protected] Robert Arnold - Associate, 415-277-1548, [email protected] Selected Consumer M&A Transactions (Approximate valuations, $ in millions) Date Equity Enterprise LTM EV / LTM Announced Effective Target Acquiror Value Value EBITDA EBITDA Universe Comments 06/10/04 Pending Unzipped Apparel (Candie's) TKO Apparel NA NA NA NA Apparel TKO Apparel to acquire Candie's jeans wear subsidiary, Unzipped Apparel 06/09/04 Pending Marshall Field's (1) May Department Stores Co. NA $3,240.0 $225.0 14.4x Retail May Department Stores to acquire Marshall Field's from Target Corp. 06/08/04 Pending Ames True Temper Inc Castle Harlan Inc NA $380.0 NA NA Consumer Products Castle Harlan to acquire garden-equipment maker Ames True Temper 06/08/04 Pending DeBas Chocolate House of Brussels Chocolates NA NA NA NA Food & Beverage House of Brussels to acquire chocolate producer DeBas Chocolate 06/08/04 06/08/04 Como Sport Windsong Allegiance Group NA NA NA NA Apparel Windsong Allegiance has acquired sportswear manufacturer Como Sport 06/08/04 06/08/04 Game for Golf LiquidGolf Holding Corp. NA NA NA NA Apparel LiquidGolf Holding Corp. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

Case3:15-cv-00612-SC Document1 Filed02/09/15 Page1 of 45 1 AMSTER, ROTHSTEIN & EBENSTEIN LLP ANTHONY F. LO CICERO, NY SBN1084698 2 [email protected] CHESTER ROTHSTEIN, NY SBN2382984 3 [email protected] MARC J. JASON, NY SBN2384832 4 [email protected] JESSICA CAPASSO, NY SBN4766283 5 [email protected] 90 Park Avenue 6 New York, NY 10016 Telephone: (212) 336-8000 7 Facsimile: (212) 336-8001 (Pro Hac Vice Applications Forthcoming) 8 HANSON BRIDGETT LLP 9 GARNER K. WENG, SBN191462 [email protected] 10 CHRISTOPHER S. WALTERS, SBN267262 [email protected] 11 425 Market Street, 26th Floor San Francisco, California 94105 12 Telephone: (415) 777-3200 Facsimile: (415) 541-9366 13 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 14 MACY'S, INC. and MACYS.COM, INC. 15 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 16 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 17 SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 18 19 MACY'S, INC. and MACYS.COM, INC., Case No. 20 Plaintiffs, COMPLAINT FOR TRADEMARK 21 INFRINGEMENT, FALSE ADVERTISING, v. FALSE DESIGNATION OF ORIGIN, 22 DILUTION, AND UNFAIR COMPETITION STRATEGIC MARKS, LLC and ELLIA 23 KASSOFF, DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL 24 Defendants. 25 26 27 28 -1- COMPLAINT Case3:15-cv-00612-SC Document1 Filed02/09/15 Page2 of 45 1 Plaintiffs Macy’s, Inc. and Macys.com, Inc. (collectively and individually “Macy’s” or 2 “Plaintiffs”), by their attorneys, for their complaint against Defendants Strategic Marks, 3 LLC (“Strategic Marks”) and Ellia Kassoff (collectively “Defendants”) allege as follows: 4 INTRODUCTION 5 1. Macy’s is commencing this action on an emergent basis to prevent the 6 expansion of Defendants’ willful, intentional and flagrant misappropriation of Macy’s 7 famous trademarks.