Thomas Merton's Gethsemani 225 and in the Society of His Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musings from Your Parish Priest

SAINTS FOR THE YEAR OF THE EUCHARIST WELCOME TO ST. PETER JULIAN EYMARD St. Peter Julian Eymard was a 19th century CATHOLIC CHURCH French priest whose devotion to the Blessed Sacra- ment expressed itself both in mystical writings and the foundation of the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament, a religious institute designed to spread 2ND SUNDAY OF LENT - FEBRUARY 28TH, 2020 devotion to the Eucharist. Throughout his life, Peter Julian was afflicted Musings from your Parish Priest: by medical problems, including a “weakness of the In ancient times, the obligation of the penitential fast throughout Lent was to take only one full lungs” and recurrent migraines. He sought solace meal a day. In addition, a smaller meal, called a collation, was allowed in the evening. In practice, this for his suffering in devotion to both Mary and the obligation, which was a matter of custom rather than of written law, was not observed Blessed Sacrament, having originally been a mem- strictly. The 1917 Code of Canon Law allowed the full meal on a fasting day to be taken at any hour ber of the Society of Mary. While serving as visitor and to be supplemented by two collations, with the quantity and the quality of the food to be -general of the society, he observed Marian com- determined by local custom. Abstinence from meat was to be observed on Ash Wednesday and on munities near Paris who practiced perpetual adora- Fridays and Saturdays in Lent. A rule of thumb is that the two collations should not add up to the tion, and was moved by the devotion and happi- equivalent of another full meal. -

Women and Men Entering Religious Life: the Entrance Class of 2018

February 2019 Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate Georgetown University Washington, DC Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 February 2019 Mary L. Gautier, Ph.D. Hellen A. Bandiho, STH, Ed.D. Thu T. Do, LHC, Ph.D. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 Major Findings ................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Characteristics of Responding Institutes and Their Entrants Institutes Reporting New Entrants in 2018 ..................................................................................... 7 Gender ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Age of the Entrance Class of 2018 ................................................................................................. 8 Country of Birth and Age at Entry to United States ....................................................................... 9 Race and Ethnic Background ........................................................................................................ 10 Religious Background .................................................................................................................. -

5211 SCHLUTER ROAD MONONA, WI 53716-2598 CITY HALL (608) 222-2525 FAX (608) 222-9225 for Immediate

5211 SCHLUTER ROAD MONONA, WI 53716-2598 CITY HALL (608) 222-2525 FAX (608) 222-9225 http://www.mymonona.com For Immediate Release Contact: Bryan Gadow, City Administrator [email protected] Monona Reaches Agreement with St. Norbert Abbey to Purchase nearly 10 Acres on Lake Monona The City of Monona has reached agreement with St. Norbert Abbey of De Pere to purchase the historic San Damiano property at 4123 Monona Drive. The purchase agreement, in the amount of $8.6M, was unanimously approved by the Monona City Council at the September 8th meeting. Pending approval by the Vatican as required by canon law, if all goes as planned Monona will take ownership of the property in June 2021. “We are very excited to have reached an agreement with St. Norbert Abbey to purchase the San Damiano property. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for Monona to significantly increase public access to the lakefront and waters of Lake Monona in addition to increasing our public open space. While Monona enjoys more than four miles of shoreline, over eighty percent of Monona residents would not have lake access were it not for our smaller parks and launches. It will be a tremendous asset for the City,” said Monona Mayor Mary O’Connor. At just under ten acres, San Damiano includes over 1,000 feet of frontage on Lake Monona. Much of the grounds are wooded. The house and property are part of the original farm developed by Allis-Chalmers heir Frank Allis in the 1880’s. The land, as is true of much of the area, was originally inhabited by Native Americans, including ancestors of the Ho- Chunk Nation. -

Provincial Reflection

VOL.48, NO.2 MAY 2017 Missionary Association of Mary Immaculate Provincial Reflection I am writing this on a 6 hour stopover with two remarkable Missionaries. One at the Hong Kong International Airport was a Spanish sister, Sister Rosario who, after having the privilege of spending after almost 40 years in northern India, a week and a half in the Philippines and and other places beforehand, came to then almost two weeks in Hong Kong/ Guangzhou at the age of 74 years, and China. I say a privilege because I have after 12 years there is going strong, with spent time with Oblates from the a passion for the people and the Lord Chinese. They continued, that although Asia/Oceania region and have visited which is infectious. The other missionary they appreciated the generosity and some of the inspiring places of their is Fr David Ullrich OMI who has spent the charity of so many, they were missionary outreach. almost 40 years in the Missions – Japan, concerned that perhaps the gifts the Hispanic Community in the USA and which came from wonderful people, The Oblates, whether in Cotabato, Manila, Mexico and now, 11 in China. They did did not meet the actual needs of the Hong Kong, Beijing or Guangzhou face not want me to mention their names people. They made mention that the many challenges (and rewards) that or their story. It needs to be told and needs of the people were not always we in the first world do not experience I will seek forgiveness when I next see in response to crises, such as the as they do. -

The Grace of God and the Travails of Contemporary Indian Catholicism Kerry P

Journal of Global Catholicism Volume 1 Issue 1 Indian Catholicism: Interventions & Article 3 Imaginings September 2016 The Grace of God and the Travails of Contemporary Indian Catholicism Kerry P. C. San Chirico Villanova University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Comparative Philosophy Commons, Cultural History Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Hindu Studies Commons, History of Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Oral History Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Practical Theology Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, Rural Sociology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social History Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation San Chirico, Kerry P. C. (2016) "The Grace of God and the Travails of Contemporary Indian Catholicism," Journal of Global Catholicism: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 3. p.56-84. DOI: 10.32436/2475-6423.1001 Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc/vol1/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. -

The Franciscan Crown in 1422, an Apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary Took Place in Assisi, to a Certain 7

History of the Franciscan Crown In 1422, an apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary took place in Assisi, to a certain 7. Assumption & Coronation Franciscan novice, named James. As a child he had a custom of daily offering a crown Vision of Friar James of roses to our Blessed Mother. When he entered the Friar Minor, he became distressed that he would no longer be able to offer this type of gift. He considered leaving when our Lady appeared to him to give him comfort and showed him another daily offering he could do. Our Lady said : “In place of the flowers that soon wither and cannot always be found, you can weave for me a crown from the flowers of your prayers … Recite one Our Father and ten How to Pray the Franciscan Crown Hail Marys while recalling the Seven Joys I experienced.” Begin with the Sign of the Cross (no creed Friar James began at once to pray as directed. or opening prayers) Meanwhile, the novice master entered and 1. Announce the first Mystery, then pray saw an angel weaving a wreath of roses and one Our Father (no Glory Be). after every tenth rose, the angel, inserted a THE 2. Pray Ten Hail Mary’s while meditating golden lily. When the wreath was finished, FRANCISCAN on the Mystery. he placed it on Friar James’ head. The novice 3. Announce second Mystery and repeat master commanded the youth to tell him CROWN one and two through the seven decades. what he had been doing; and Friar James 4. -

A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St

Clemson University TigerPrints Master of Architecture Terminal Projects Non-thesis final projects 12-1986 A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St. Benedict. Fairfield ounC ty, South Carolina Timothy Lee Maguire Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp Recommended Citation Maguire, Timothy Lee, "A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St. Benedict. Fairfield County, South Carolina" (1986). Master of Architecture Terminal Projects. 26. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp/26 This Terminal Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Non-thesis final projects at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Architecture Terminal Projects by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MONASTERY FOR THE BROTHERS OF THE ORDER OF CISTERCIANS OF THE STRICT OBSERVANCE OF THE RULE OF ST. BENEDICT. Fairfield County, South Carolina A terminal project presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University in partial fulfillment for the professional degree Master of Architecture. Timothy Lee Maguire December 1986 Peter R. Lee e Id Wa er Committee Chairman Committee Member JI shimoto Ken th Russo ommittee Member Head, Architectural Studies Eve yn C. Voelker Ja Committee Member De of Architecture • ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . J Special thanks to Professor Peter Lee for his criticism throughout this project. Special thanks also to Dale Hutton. And a hearty thanks to: Roy Smith Becky Wiegman Vince Wiegman Bob Tallarico Matthew Rice Bill Cheney Binford Jennings Tim Brown Thomas Merton DEDICATION . -

The Book of Margery Kempe- Medieval Mysticism and Sanity Abstract: Since the Discovery of Margery Kempe's Book the Validity O

1 The Book of Margery Kempe- Medieval Mysticism and Sanity Abstract: Since the discovery of Margery Kempe’s Book the validity of her visionary experiences has been called scrutinized by those within the literary and medical communies. Indeed there were many individuals when The Book was written, including her very own scribe, who have questioned Kempe’s sanity. Kempe claimed herself to be an unusual woman who was prone to visionary experiences of divine nature that were often accompanied by loud lamenting, crying, and shaking and self-inflicted punishment. By admission these antics were off-putting to many and at times even disturbing to those closest to her. But is The Book of Margery Kempe a tale of madness? It is unfair to judge all medieval mystics as hysterics. Margery Kempe through her persistence and use of scribes has given a first-hand account of life as a mystic in the early 15th century. English Literature 2410-1N Fall/2011 Deb Koelling 2 The Book of Margery Kempe- Medieval Mysticism and Sanity The Book Margery Kempe tells the story of medieval mystic Margery Kempe’s transformation from sinner to saint by her own recollections, beginning at the time of the birth of her first of 14 children. Kempe (ca. 1373-1438) tells of being troubled by an unnamed sin, tortured by the devil, and being locked away, with her hands bound for fear she would injure herself; for greater than six months, when she had her first visionary experience of Jesus dressed in purple silk by her bedside. Kempe relates: Our merciful Lord Christ Jesus, ever -

{Download PDF} the Way of Unknowing : Expanding Spiritual

THE WAY OF UNKNOWING : EXPANDING SPIRITUAL HORIZONS THROUGH MEDITATION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Main | 144 pages | 30 Apr 2012 | CANTERBURY PRESS NORWICH | 9781848251182 | English | London, United Kingdom The Way of Unknowing : Expanding Spiritual Horizons Through Meditation PDF Book More recently, the practices of Christian Meditation through the World Community for Christian Meditation , and Centering Prayer represent contemporary expressions of the rich tradition of Christian meditation. By July , we had 76 people registered, a number that far exceeded my wildest dreams. Although mystical experiences of divine warmth, sweetness, and song may have some spiritual value, they will often remain distractions to you in the process of piercing the cloud of unknowing So keep lifting your love up to that cloud. But not everyone is going to get it. With one click, I was in the video chapel with about 14 other people from six different countries. Do you remember what happened to the greedy beasts who approached the cloud of unknowing on Mount Sinai? More importantly, these generally good thoughts can still distract you from the contemplative life: the deeper work of loving God in the darkness. When out walking somewhere, have you ever followed your feet while being curious about where they might lead? Columba arrived in the 6 th century to found a monastery and give birth to Celtic Christianity in Scotland. If this prayer practice resonates with you, then I urge you to read these words of mine again. I needed to take this deep book about meditation in the context of Christianity in small doses, reading it over a period of months, even though it is fairly short. -

The Maronite Catholic Church in the Holy Land

The Maronite Catholic Church in the Holy Land The maronite church of Our Lady of Annunciation in Nazareth Deacon Habib Sandy from Haifa, in Israel, presents in this article one of the Catholic communities of the Holy Land, the Maronites. The Maronite Church was founded between the late 4th and early 5th century in Antioch (in the north of present-day Syria). Its founder, St. Maron, was a monk around whom a community began to grow. Over the centuries, the Maronite Church was the only Eastern Church to always be in full communion of faith with the Apostolic See of Rome. This is a Catholic Eastern Rite (Syrian-Antiochian). Today, there are about three million Maronites worldwide, including nearly a million in Lebanon. Present times are particularly severe for Eastern Christians. While we are monitoring the situation in Syria and Iraq on a daily basis, we are very concerned about the situation of Christians in other countries like Libya and Egypt. It’s true that the situation of Christians in the Holy Land is acceptable in terms of safety, however, there is cause for concern given the events that took place against Churches and monasteries, and the recent fire, an act committed against the Tabgha Monastery on the Sea of Galilee. Unfortunately in Israeli society there are some Jewish fanatics, encouraged by figures such as Bentsi Gopstein declaring his animosity against Christians and calling his followers to eradicate all that is not Jewish in the Holy Land. This last statement is especially serious and threatens the Christian presence which makes up only 2% of the population in Israel and Palestine. -

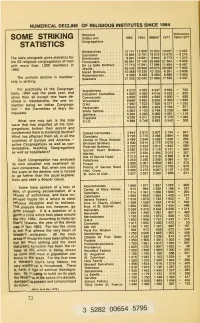

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

Liturgical Press Style Guide

STYLE GUIDE LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org STYLE GUIDE Seventh Edition Prepared by the Editorial and Production Staff of Liturgical Press LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover design by Ann Blattner © 1980, 1983, 1990, 1997, 2001, 2004, 2008 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. Printed in the United States of America. Contents Introduction 5 To the Author 5 Statement of Aims 5 1. Submitting a Manuscript 7 2. Formatting an Accepted Manuscript 8 3. Style 9 Quotations 10 Bibliography and Notes 11 Capitalization 14 Pronouns 22 Titles in English 22 Foreign-language Titles 22 Titles of Persons 24 Titles of Places and Structures 24 Citing Scripture References 25 Citing the Rule of Benedict 26 Citing Vatican Documents 27 Using Catechetical Material 27 Citing Papal, Curial, Conciliar, and Episcopal Documents 27 Citing the Summa Theologiae 28 Numbers 28 Plurals and Possessives 28 Bias-free Language 28 4. Process of Publication 30 Copyediting and Designing 30 Typesetting and Proofreading 30 Marketing and Advertising 33 3 5. Parts of the Work: Author Responsibilities 33 Front Matter 33 In the Text 35 Back Matter 36 Summary of Author Responsibilities 36 6. Notes for Translators 37 Additions to the Text 37 Rearrangement of the Text 37 Restoring Bibliographical References 37 Sample Permission Letter 38 Sample Release Form 39 4 Introduction To the Author Thank you for choosing Liturgical Press as the possible publisher of your manuscript.