A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuum: Laying a Foundation Winter 2008

Laying a foundation Between 1955 and 1958, the newly arrived Cistercians helped found the University of Dallas, carved out a piece of land, and built a monastery. By Brian Melton ’71 Editor’s note: This is the third in an occasional series of stories cel- Not that there was anything to complain about when it came to their ebratng the Cistercian’s 50 years in Texas. new digs in Texas. February found the fi rst seven monks (Frs. Damian Szödény, Thomas Fehér, Lambert Simon, Benedict Monostori, George, y 1955, things fi nally seemed to be going right for the Christopher Rábay, and Odo) living and working at Our Lady of Vic- beleaguered Hungarian Cistercians. Behind them lay tory in Fort Worth and several other parishes and schools throughout two intensely traumatic experiences: fi rst, their har- Dallas. And when Fr. Anselm Nagy came down from Wisconsin in the rowing escape from Soviet authorities back home, and spring, he established residence at the former Bishop Lynch’s stately second, the bitter disagreement with their own abbot mansion on Dallas’s tony Swiss Avenue (4946), which became the un- Bgeneral from Rome, Sighard Kleiner. His autocratic, imperious or- offi cial gathering place of his new little fl ock. ders for them — to live a life of contemplative farm work and prayer Even better, permission for a Cistercian residence in Dallas came at the tiny Spring Bank Monastery in Wisconsin — sat about as well straight from the Holy See and sailed effortlessly through the di- as the forced Soviet suppression of their beloved abbey back home ocesan attorney’s offi ce in March, as did the incipient monastery’s in Zirc (pronounced “Zeerts”), Hungary. -

The Grace of God and the Travails of Contemporary Indian Catholicism Kerry P

Journal of Global Catholicism Volume 1 Issue 1 Indian Catholicism: Interventions & Article 3 Imaginings September 2016 The Grace of God and the Travails of Contemporary Indian Catholicism Kerry P. C. San Chirico Villanova University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Comparative Philosophy Commons, Cultural History Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Hindu Studies Commons, History of Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Oral History Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Practical Theology Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, Rural Sociology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social History Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation San Chirico, Kerry P. C. (2016) "The Grace of God and the Travails of Contemporary Indian Catholicism," Journal of Global Catholicism: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 3. p.56-84. DOI: 10.32436/2475-6423.1001 Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc/vol1/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. -

The Book of Margery Kempe- Medieval Mysticism and Sanity Abstract: Since the Discovery of Margery Kempe's Book the Validity O

1 The Book of Margery Kempe- Medieval Mysticism and Sanity Abstract: Since the discovery of Margery Kempe’s Book the validity of her visionary experiences has been called scrutinized by those within the literary and medical communies. Indeed there were many individuals when The Book was written, including her very own scribe, who have questioned Kempe’s sanity. Kempe claimed herself to be an unusual woman who was prone to visionary experiences of divine nature that were often accompanied by loud lamenting, crying, and shaking and self-inflicted punishment. By admission these antics were off-putting to many and at times even disturbing to those closest to her. But is The Book of Margery Kempe a tale of madness? It is unfair to judge all medieval mystics as hysterics. Margery Kempe through her persistence and use of scribes has given a first-hand account of life as a mystic in the early 15th century. English Literature 2410-1N Fall/2011 Deb Koelling 2 The Book of Margery Kempe- Medieval Mysticism and Sanity The Book Margery Kempe tells the story of medieval mystic Margery Kempe’s transformation from sinner to saint by her own recollections, beginning at the time of the birth of her first of 14 children. Kempe (ca. 1373-1438) tells of being troubled by an unnamed sin, tortured by the devil, and being locked away, with her hands bound for fear she would injure herself; for greater than six months, when she had her first visionary experience of Jesus dressed in purple silk by her bedside. Kempe relates: Our merciful Lord Christ Jesus, ever -

The Maronite Catholic Church in the Holy Land

The Maronite Catholic Church in the Holy Land The maronite church of Our Lady of Annunciation in Nazareth Deacon Habib Sandy from Haifa, in Israel, presents in this article one of the Catholic communities of the Holy Land, the Maronites. The Maronite Church was founded between the late 4th and early 5th century in Antioch (in the north of present-day Syria). Its founder, St. Maron, was a monk around whom a community began to grow. Over the centuries, the Maronite Church was the only Eastern Church to always be in full communion of faith with the Apostolic See of Rome. This is a Catholic Eastern Rite (Syrian-Antiochian). Today, there are about three million Maronites worldwide, including nearly a million in Lebanon. Present times are particularly severe for Eastern Christians. While we are monitoring the situation in Syria and Iraq on a daily basis, we are very concerned about the situation of Christians in other countries like Libya and Egypt. It’s true that the situation of Christians in the Holy Land is acceptable in terms of safety, however, there is cause for concern given the events that took place against Churches and monasteries, and the recent fire, an act committed against the Tabgha Monastery on the Sea of Galilee. Unfortunately in Israeli society there are some Jewish fanatics, encouraged by figures such as Bentsi Gopstein declaring his animosity against Christians and calling his followers to eradicate all that is not Jewish in the Holy Land. This last statement is especially serious and threatens the Christian presence which makes up only 2% of the population in Israel and Palestine. -

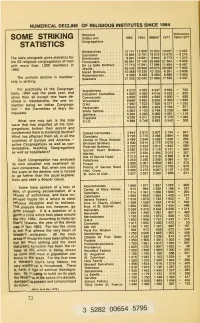

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

The Jesuits Founded on This Day, September 27, 1540

The Jesuits Founded on this day, September 27, 1540 I. Development of Religious “Orders” prior to the Jesuits Monastic -- ordinary and strict varieties (Benedictines, Carthusians, Cistercians, etc.) Western monasteries descend from Benedict of Nursia, + 547 Mendicant -- Dominicans (founded 1216) and Franciscans (founded 1209) Clerks Regular -- Renaissance development of organized groups of priests living together focused on pastoral care of people; they lived together under a common spiritual rule, becoming an effective method to reform local clergy II Iñigo de Loyola – Ignatius of Loyola (1493-1556) Early life as soldier, sickness, convalescence, period of intense & neurotic religiosity Discovery of spiritual “exercises”, determination to become a priest, study at Paris Formation of a group of colleagues, vows, idea of reaching the Holy Land Eventual arrival in Rome to offer themselves to whatever service the Pope desired Society of Jesus granted its existence September 27, 1540 Ignatius hereafter becomes an administrator of an ecclesiastical juggernaut III Discipline and Flexibility as the marks of the order •How do they live together? They don’t, necessarily. They travel a lot (at least corporately). •What do Jesuits do? Whatever needs doing or whatever special mission the Pope assigns. •Variety of Jesuit ministries: education of lay people; education of clergy; global missions; parish work; research; communication; spiritual retreats; writing •How did the Jesuits found schools and universities? (27 in USA) (Joke about Bethlehem) IV Significant moments Adherence to social elites, wealth, influence, and eventual suppression of the Order (1773) (My landlady in Dublin; McCann’s Grandmother) Expulsion of Jesuits from France, Spain, Portugal 1757-1770 Revival of Order (1814) and strict adherence to the Papacy Liberalization of the Order in the 1900s and criticism of Vatican (1970s), reined in by Pope (1980s) V Reformulation of the Jesuits’ Mission, 1975: heightened focus on social justice (Examples: El Salvador, Nicaragua) (Example Cristo Rey Network) “ . -

Jesuit Urban Mission

Jesuit Urban Mission Bernard loved the hills, Benedict the valleys, Francis the towns, Ignatius great cities. This brief couplet of unknown origin captures in a few words the distinct charisms of four saints and founders of religious communities in the Church— the Cistercians, the Benedictines, the Franciscans and the Jesuits. Ignatius of Loyola, who founded the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits), placed much focus on the plight of the poor in the great cities of his time. In his Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius imagined God gazing upon the teeming masses of our cities, on men and women sick and dying, the old and young, the rich and the poor, the happy and sad, some being born and some being laid to rest. Surrounded by that mass of human need, Ignatius was 63 moved by a God who joyfully opted to 60 At Rome he founds public works of piety: hospices for In Rome, he renews the practice of frequenting women in bad marriages; for virgins at [the church of] step into the pain of human suffering and the sacraments and of giving devout sermons and Santa Caterina dei Funari, for [orphan] girls at [the became flesh, sharing fully all our human introduces ways of passing on the rudiments of church of] Santi Quattro Coronati, also for orphan Christian doctrine to youth in the churches and boys wandering through the city as beggars, a residence joys and sorrows. squares of Rome. Peter Balais, S.J. Plates 60, 63. Vita beati patris Ignatii Loiolae for [Jewish] catechumens, as well as other residences The Illustrated Life of Ignatius of Loyola, and colleges, to the profit and with the admiration of Jesuit Refugee Service published in Rome in 1609 to celebrate Ignatius’ beatification that year by Pope Paul V. -

The Girl Who Woke the Moon Zach Bennett Lisabeth Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2019 Shattered: The girl who woke the moon Zach Bennett Lisabeth Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Lisabeth, Zach Bennett, "Shattered: The girl who woke the moon" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 17245. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/17245 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shattered: The girl who woke the moon by Zach Lisabeth A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Major: Creative Writing and Environment Program of Study Committee: David Zimmerman, Major Professor Kenneth L. Cook Margaret Holmgren Jeremy Withers The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this thesis the Graduate College will ensure this thesis is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2019 Copyright © Zach Lisabeth, 2019. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: THE GIRL WHO WOKE THE MOON 1 CHAPTER 2: FLYSWATTER 18 CHAPTER 3: NYAMURA VILLAGE 33 CHAPTER 4: FULL MOON RITES 55 CHAPTER 5: CETACEAN 77 CHAPTER 6: INCARNATION 100 CHAPTER 7: ANOTHER LIFE 117 CHAPTER 8: THE FUTURE 139 CHAPTER 9: GITA’S PROMISE 153 REFERENCES 178 1 CHAPTER 1: THE GIRL WHO WOKE THE MOON Gita screamed loud enough to wake the Nereids from their millennial sleep at the bottom of the sea. -

Archivio Generale St. Louis Province

INVENTORY OF THE ST. LOUIS PROVINCE COLLECTION (12) REDEMPTORIST GENERAL ARCHIVE, ROME Prepared by Patrick J. Hayes, Ph.D., Archivist Redemptorist Archives of the Baltimore Province 7509 Shore Road Brooklyn, New York, USA 11209 718-833-1900 Email: [email protected] The Redemptorists’ Denver Province (12) has a historic beginning and storied career. Formally erected as a sister province of the Baltimore Province in 1875, it was initially known as the Vice-Province of St. Louis. It eventually divided again between regional foundations in Chicago, New Orleans, and Oakland. The Denver Province presently affiliates with the Vice- Provinces of Bangkok and Manaus and hosts the external province of Vietnam. Today, the classification system at the Archivio Generale Redentoristi (AGR), has retained the name of the original St. Louis Province in identifying the collection associated with this unit of the Redemptorist family. A good place to begin to understand the various permutations of the St. Louis Province is through the work of Father Peter Geiermann’s Annals of the St. Louis Province (1924) in three thick volumes. Unfortunately, it has never been updated. The Province awaits its own full-scale history. The St. Louis Province covered a large swath of the United States at one point—from Whittier, California to Detroit, Michigan and Seattle, Washington to New Orleans, Louisiana. Redemptorists of this province were present in cities such as Wichita and Kansas City, Fresno and Grand Rapids, San Francisco and San Antonio. Their formation houses reached into Missouri, Illinois, and Wisconsin. Schools could be found in Oakland and Detroit. Their shrines in Chicago, New Orleans, and St. -

May 26, 2000 Vol

Inside Archbishop Buechlein . 4, 5 Editorial. 4 From the Archives. 25 Question Corner . 11 TheCriterion Sunday & Daily Readings. 11 Criterion Vacation/Travel Supplement . 13 Serving the Church in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 www.archindy.org May 26, 2000 Vol. XXXIX, No. 33 50¢ Two men to be ordained to the priesthood By Margaret Nelson His first serious study of religion was of 1979—four months into the Iran civil his sister and her husband when he was 6 Islam, when he began to teach in Saudi war. years old. Archbishop Daniel M. Buechlein will Arabia. A history professor there, “a wise “I approached the nearest Catholic At his confir- ordain two men to the priesthood for the man from Iraq” who spoke fluent English, Church—St. Joan of Arc in Indianapolis.” mation in 1979, Archdiocese of Indianapolis at 11 a.m. on talked with him He asked Father Donald Schmidlin for Borders didn’t June 3 at SS. Peter and Paul Cathedral in about his own instructions. Since that was before the think of the Indianapolis. faith. Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults priesthood. He They are Larry Borders of St. Mag- “He knew process was so widespread, he met with had been negoti- dalen Parish in New Marion—who spent more about the priest and two other men every week ating a teaching two decades overseas teaching lan- Christianity than or so. job in Japan to guages—and Russell Zint of St. Monica I knew about The week before Christmas in 1979, begin a 15-year Parish in Indianapolis—who studied engi- my own tradi- Borders was confirmed into the Catholic contract. -

Interview No. 158

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Combined Interviews Institute of Oral History 3-18-1973 Interview no. 158 Brother M. Paul Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/interviews Part of the Oral History Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Interview with Brother M. Paul by Fletcher Newman, 1973, "Interview no. 158," Institute of Oral History, University of Texas at El Paso. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Oral History at ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Combined Interviews by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITYOF TEXASAT EL PASO INSTITUTEOF ORALHISTORY INTERVIEI'IEE: BrotherM. Paul INTERVIE}lER: Fletcher Newman PROJECT: .|973 DATEOF INTERVIEil: March18, TERT'{SOF USE: Unrestricted TAPENO.: .l58 TRANSCRIPTIIO.: TRANSCRItsER: DATETRANSCRIBED: BIOGRAPHICALSYNOPSIS OF INTERVIEWEE: Monk. SUi"ii{ARY0F IIiTERVIEt'l: Travelsin Spain,Francenand the UnitedStates. (Part of a paperwritten by FletcherNewrnan) 13 pages. BrotfrerPaul by Fletcher.|8, .| Newman March 973 Tnncd fnterview pau1, vith _Brother 14. Mlarch tg, ]g-i_1 [F:N. is tire intervier^rer; B.p. is Brother paul. ] F.N. Mrnt do carthusians think of abbots, since they donrt have them? B.P. carthusians donrt think much of abbots, thatrs for sure. F.N. Donft they respect euthority? B.P. They do. In the last anaLysis, when the prior comes by, they kiss the hem of his hebit and. kneel till he finishes speaking, Just as other monks kneel and kiss the abbotfs ring. But somewhereback ln distant history they d.ecided they d.idnft need. -

How to Address Priests and Religious: Titles and Signs of Respect

How to Address Priests and Religious: Titles and Signs of Respect Marian Therese Horvat, Ph.D. Before me are several interesting questions on how we should address priests and religious men and women sent to my desk recently by a lady. I will answer them today on the TIA website, since I think that my correspondent is not the only one with similar queries. In times past every Catholic used to know some of the simple rules that have been set aside from disuse. The general protocol was taught by sisters in grade school, but more often was learned as in osmosis from everyday practice. No one dreamed of calling Father O’Reilly by the nickname “Bill,” or, addressing Sister Margaret Mary as “Maggie.” Everyone knew you rose as a sign of respect when a priest or religious entered the room. Speaking before a gathering that included clergy or religious, a Catholic speaker as habit addressed them solemnly first. The dignified sisters inspired respect. Above, a sister teaches protocol in a pre-Vatican II Catholic classroom. But then came the tumultuous and leveling aftermath of Vatican II that spelled a death to formalities in the religious sphere. Priests, monks and sisters began to adopt the ways of a world that were becoming increasingly vulgar and egalitarian. Distinguishing titles and marks of respect were considered alienating and only for old- fashioned “establishment” people who were afraid to embrace the “signs of the times.” In the spirit of adaptation to the world, the cassock and habit were abandoned, along with the formal signs of respect paid to the persons who wore them.