80S AGAIN! a MONOGRAPH on the 1980S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nirvana W Latach 80

seria Z WEHIKUŁEM, tom I: 80s AGAIN! MONOGRAFIA POŚWIĘCONA LATOM 80. XX WIEKU redakcja: Aneta Jabłońska i Mariusz Koryciński Pewne prawa zastrzeżone | Klub Filmowy im. Jolanty Słobodzian | Warszawa 2017 ISBN (wersja elektroniczna): 978-83-64111-79-2 ISBN (wersja drukowana): 978-83-64111-75-4 ABSTRAKT | Paweł Jaskulski w artykule Początki nicości. Nirvana w latach 80. opisuje mniej znany okres istnienia Nirvany. Wprowadzając w tematykę, zastanawia się nad recepcją muzyki rockowej, postrzeganej przez niektórych jako gorszy rodzaj sztuki; przedstawia także narodziny grunge’u – nurtu, który powstał w Stanach Zjednoczonych właśnie w latach 80. XX wieku. Zarysowuje również historię pierwszych – przygotowywanych w chałupniczych warunkach – sesji nagraniowych; genezę debiutanckiej płyty oraz ulubione piosenki Kurta Cobaina. Jaskulski analizuje następnie dokonania Cobaina i Krisa Novoselica z tamtej dekady, wyróżniając następujące obszary refleksji: strategię związaną z nazewnictwem utworów zespołu, sposób kontaktu zespołu z jego odbiorcami oraz autokreację lidera grupy. Pojawia się także wątek płyty Nevermind, pochodzącej wprawdzie z 1991 roku, stanowiącej jednak podsumowanie działalności zespołu z poprzedniej dekady. Paweł Jaskulski [email protected] doktorant na Wydziale Polonistyki Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, gdzie prowadzi zajęcia o kinie. Współredaktor interaktywnego tomu Różne oblicza edukacji audiowizualnej. Autor rozdziałów w monografiach Kultura rocka. Twórcy-tematy-motywy (2); NieZwykłe inspiracje spoza kadru oraz Różne oblicza edukacji audiowizualnej. Publikował na łamach m.in. „Twórczości”, „Odry”, „Nowego Folderu” oraz portali historia.org.pl i publica.pl. Współorganizator konferencji ogólnopolskich („O poprawie polskiego kina”) i międzynarodowych („Edukacja audiowizualna i medialna w Polsce i świecie”); współrealizator kursu „Jak przygotować projekt filmu dokumentalnego?”. Należy do Polskiego Towarzystwa Badań nad Filmem i Mediami. Klub Filmowy im. Jolanty Słobodzian powstał, aby upamiętnić polską reżyserkę i niestrudzoną edukatorkę filmową. -

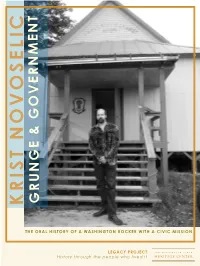

Krist Novoselic

OVERNMENT G & E GRUNG KRIST NOVOSELIC THE ORAL HISTORY OF A WASHINGTON ROCKER WITH A CIVIC MISSION LEGACY PROJECT History through the people who lived it Krist Novoselic Research by John Hughes and Lori Larson Transcripti on by Lori Larson Interviews by John Hughes October 14, 2008 John Hughes: This is October 14, 2008. I’m John Hughes, Chief Oral Historian for the Washington State Legacy Project, with the Offi ce of the Secretary of State. We’re in Deep River, Wash., at the home of Krist Novoselic, a 1984 graduate of Aberdeen High School; a founding member of the band Nirvana with his good friend Kurt Cobain; politi cal acti vist, chairman of the Wahkiakum County Democrati c Party, author, fi lmmaker, photographer, blogger, part-ti me radio host, While doing reseach at the State Archives in 2005, Novoselic volunteer disc jockey, worthy master of the Grays points to Grays River in Wahkiakum County, where he lives. Courtesy Washington State Archives River Grange, gentleman farmer, private pilot, former commercial painter, ex-fast food worker, proud son of Croati a, and an amateur Volkswagen mechanic. Does that prett y well cover it, Krist? Novoselic: And chairman of FairVote to change our democracy. Hughes: You know if you ever decide to run for politi cal offi ce, your life is prett y much an open book. And half of it’s on YouTube, like when you tried for the Guinness Book of World Records bass toss on stage with Nirvana and it hits you on the head, and then Kurt (Cobain) kicked you in the butt . -

Mechanisms of Control in Alan Moore's "V for Vendetta" and George Orwell's "1984"

Mechanisms of Control in Alan Moore's "V for Vendetta" and George Orwell's "1984" Prtenjača, Zvonimir Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2018 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:668248 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskoga jezika i književnosti i povijesti Zvonimir Prtenjača Mehanizmi kontrole u romanima "O za osvetu" Alana Moorea i "1984." Georgea Orwella Završni rad Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2018. Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskoga jezika i književnosti i povijesti Zvonimir Prtenjača Mehanizmi kontrole u romanima "O za osvetu" Alana Moorea i "1984." Georgea Orwella Završni rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2018. J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme -

Foundation the International Review of Science Fiction Foundation 119 the International Review of Science Fiction

Foundation The International Review of Science Fiction Foundation 119 The International Review of Science Fiction In this issue: Matt Englund reassesses Philip K. Dick’s Galactic Pot Healer George A. Gonzalez explores US military policy in Star Trek Foundation Samantha Kountz analyses the representation of immigration in post-war sf cinema Erica Moore evaluates the post-Darwinism of J.G. Ballard’s Crash Nick Hubble reflects on the legacy of 2000 AD Iain M. Banks and Kim Stanley Robinson in conversation on the subject of utopia Vol. 43 No.119 2014 43 No.119 Vol. Conference reports by Paul Kincaid, Paul March-Russell and Robin Anne Reid In addition, there are reviews by: Jeremy Brett, Molly Cobb, Leimar Garcia-Siino, Lincoln Geraghty, Grace Halden, Andrew Hedgecock, Anna McFarlane, Joe Norman, Andy Sawyer, Will Slocombe, Tom Sykes and Michelle K. Yost Of books by: Jeannette Baxter and Rowland Wymer, David Brittain, Stefan Ekman, Simon Ings, Graham Joyce, Paul McAuley, Howard E. McCurdy, Jonathan Oliver, Christopher Sims, Graham Sleight, David C. Smith, and Thomas Van Parys and I.Q. Hunter Cover image/credit: Ian Gibson Foundation is published three times a year by the Science Fiction Foundation (Registered Charity no. 1041052). It is typeset and printed by The Lavenham Press Ltd., 47 Water Street, Lavenham, Suffolk, CO10 9RD. Foundation is a peer-reviewed journal. Subscription rates for 2015 Individuals (three numbers) United Kingdom £20.00 Europe (inc. Eire) £22.00 Rest of the world £25.00 / $42.00 (U.S.A.) Student discount £14.00 / $23.00 (U.S.A.) Institutions (three numbers) Anywhere £42.00 / $75.00 (U.S.A.) Airmail surcharge £7.00 / $12.00 (U.S.A.) Single issues of Foundation can also be bought for £7.00 / $15.00 (U.S.A.). -

V for Vendetta

Study Guide: V For Vendetta popular in that title; during the 26 issues of Warrior several covers featured V for Vendetta. When the publishers cancelled Warrior in 1985 (with two completed issues unpublished due to the cancellation), several companies attempted to convince Moore and Lloyd to let them publish and complete the story. In 1988 DC Comics published a ten-issue series that reprinted the Warrior stories in color, then continued the series to completion. The first new material appeared in issue #7, which included the unpublished episodes that would have appeared in Warrior #27 and #28. Tony Weare drew one chapter ("Vincent") and contributed additional art to two others ("Valerie" and "The Vacation"); Steve Whitaker and Siobhan Dodds worked as colourists on the entire series. The series, including Moore's "Behind the Painted ! Smile" essay and two "interludes" outside the central continuity, then appeared in collected form as a trade The complete film script of V for Vendetta is paperback, published in the US by DC's Vertigo imprint available from the Internet Movie Script Database: (ISBN 0-930289-52-8) and in the UK by Titan Books http://www.imsdb.com/scripts/V-for-Vendetta.html (ISBN 1-85286-291-2). V for Vendetta is a ten-issue comic book series written by Alan Moore and illustrated mostly by David Background Lloyd, set in a dystopian future United Kingdom David Lloyd's paintings for V for Vendetta in imagined from the 1980s to about the 1990s. A Warrior originally appeared in black-and-white. The DC mysterious masked revolutionary who calls himself "V" Comics version published the artwork "colourised" in works to destroy the totalitarian government, profoundly pastels. -

Universidade Federal De Minas Gerais Faculdade De Filosofia E Ciências Humanas Departamento De História REPRESENTAÇÕES POLÍ

1 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas Departamento de História REPRESENTAÇÕES POLÍTICAS DA GUERRA FRIA: AS HISTÓRIAS EM QUADRINHOS DE ALAN MOORE NA DÉCADA DE 1980 . Márcio dos Santos Rodrigues 2011 2 Márcio dos Santos Rodrigues REPRESENTAÇÕES POLÍTICAS DA GUERRA FRIA: AS HISTÓRIAS EM QUADRINHOS DE ALAN MOORE NA DÉCADA DE 1980 Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação Historia da Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em História Linha de Pesquisa: História e Culturas Políticas Orientador: Prof. Dr. Rodrigo Patto Sá Motta . 2011 3 907.2 Rodrigues, Márcio dos Santos R696r Representações políticas da Guerra Fria [manuscrito] : as histórias em 2011 quadrinhos de Alan Moore na década de 1980 / Márcio dos Santos Rodrigues. – 2011. 212 f. Orientador: Rodrigo Patto Sá Motta. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências. 1. Moore, Alan . 2. História – Teses. 3. História em quadrinhos – Teses. 4.Guerra fria - Teses . I. Motta, Rodrigo Patto Sá. II. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Faculdade de Filosofia. III. Título. 4 Representações políticas da Guerra Fria: As Histórias em Quadrinhos de Alan Moore na década de 1980 Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação Historia da Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em História Banca Examinadora: _________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Rodrigo Patto Sá Motta (Orientador - UFMG) _________________________________________________________ Prof.Dr. João Pinto Furtado (UFMG) _________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Carlos Eduardo Barbosa Sarmento (CPDOC/FGV) _________________________________________________________ Profa Dr a. -

The V's Motivation of Being a Terrorist As Seen in Alan

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI V’S MOTIVATION OF BEING A TERRORIST AS SEEN IN ALAN MOORE’S V FOR VENDETTA GRAPHIC NOVEL A SARJANA PENDIDIKAN THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By Andreas Leo Kresnawan Putra Student Number: 131214163 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2018 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI V’S MOTIVATION OF BEING A TERRORIST AS SEEN IN ALAN MOORE’S V FOR VENDETTA GRAPHIC NOVEL A SARJANA PENDIDIKAN THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By Andreas Leo Kresnawan Putra Student Number: 131214163 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2018 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI “It gives me strength to have somebody to fight for; I can never fight for myself, but, for others, I can kill.” Emilie Autumn, The Asylum for Wayward Victorian Girls This thesis is dedicated to: My Parents Cyprianus Louis Noviatno And Agnes Widyastuti “Being deeply loved by someone gives you strength, while loving someone deeply gives you courage.” Lao Tzu iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI STATEMENT OF WORK’S ORIGINALITY I honestly declare that this thesis, which I have written, does not contain the work or parts of the work of other people, except those cited in the quotations and the references, as a scientific paper should. -

Issue 10; Vol. 3, No. 1 (Fall, 2006)

SSOOMMEE FFAANNTTAASSTTIICC Issue #10, Fall, 2006 An Interview with Elizabeth Bear Vol. 3, No. 1 by Matthew Appleton http://www.somefantastic.us/ Born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1971, Elizabeth attended the ISSN # 1555-2241 University of Connecticut, studying English and Anthropology, but Features did not graduate. She worked in a variety of occupations during the An Interview with Elizabeth Bear, 1 ‘90s, selling a few stories to small‐press publications along the way. by Matthew Appleton She began writing earnestly in 2001 and has produced numerous King Kong as Reality Television, 19 novels and short stories since. by Sara K. Ellis In 2005, she won the Campbell Award for Best New Writer and A Double-Take on V for Vendetta, 21 by Richard Fuller saw the publication of Jenny Casey trilogy—actually a single novel broken into three volumes: Hammered, Scardown and World‐ Book/Graphic Novel Reviews wired—which collectively won the 2006 Locus Award for Best Sex in the System, edited by Cecilia 8 First Novel. Her first short story collection, The Chains that You Tan; reviewed by Rose Fox Refuse, was released earlier this year as well as the first book in her Shuteye for the Timebroker, by Paul Di 10 sprawling Promethean Age fantasy series, Blood & Iron. A new Filippo; reviewed by Danny Adams science fiction novel, Carnival, will arrive in stores at the end of Monster Island, by David Wellington; 13 reviewed by Matthew Appleton November and the next Promethean Age novel, Whiskey & Water, A Shadow in Summer, by Daniel 15 is due out in 2007. -

Nirvana & the Sound of Seattle

"Я здесь, с вами, чтобы забрать вас с собой прямо в Нирвану" Биография Курта Кобейна. ~Nirvana & The Sound Of Seattle~ http://www.kurtcobain.ru [email protected] ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ В 1990 году ни один из рок-альбомов в Соединенных Штатах не вышел на первое место, что дало повод специалистам заговорить о конце эры рока. Музыкальная аудитория была к этому времени тщательно классифицирована руководителями радиопрограмм в соответствии с демографическими данными, и казалось маловероятным, что рок-фэны смогут объединиться вокруг какого-нибудь одного диска в достаточно большом количестве, чтобы вывести его на первые места в чартах. Дегенерация рока в выхолощенный и рафинированный мнимый бунт привела к тому, что его место заняли такие жанры, как кантри и рэп, непосредственно обращавшиеся к настроениям и заботам масс. И хотя в 1991 году на первое место вышли несколько рок-альбомов, лишь Nevermind объединил аудиторию, которая до этого никогда не была единой - десяти-двадцатилетних. Устав от набивших оскомину ветеранов вроде GENESIS и Эрика Клэптона или искусственных созданий вроде Полы Абдул и MILLI VANILLI, тинэйджеры нуждались в собственной музыке. Такой, которая бы выражала то, что они чувствуют. Они уже догадывались, что стали первым поколением в истории Америки, лишенным надежды на лучшую жизнь в сравнении с жизнью своих родителей, поколением, первые сексуальные опыты которого были омрачены угрозой СПИДа, а детство прошло в страхе перед призраком ядерной войны. Они не чувствовали в себе сил, чтобы бороться с враждебным окружением и вынести атмосферу сексуального и культурного подавления, насаждаемого режимами Рейгана и Буша. Перед лицом всего этого они ощущали себя беспомощными и безгласными. В 80- е годы многие музыканты выражали недовольство политической и социальной несправедливостью, однако большинство из них, такие как Дон Хенли, Брюс Спрингстин и Стинг, являлись представителями старшего поколения. -

A Bio-Political Reading of 20Th Century Latin American and Anglo-Saxon Science Fiction Juan David Cruz University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Through the Spaceship’s Window: A Bio-political Reading of 20th Century Latin American and Anglo-Saxon Science Fiction Juan David Cruz University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Cruz, J. D.(2018). Through the Spaceship’s Window: A Bio-political Reading of 20th Century Latin American and Anglo-Saxon Science Fiction. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4735 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Through the Spaceship’s Window: A Bio-political Reading of 20th Century Latin American and Anglo-Saxon Science Fiction by Juan David Cruz Bachelor of Arts Univeridad de los Andes, 2009 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2012 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: Jorge Camacho, Major Professor Héctor D. Fernández L’Hoeste, Committee Member Meili Steele, Committee Member Alexander J. Beecroft, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Juan David Cruz, 2018 All Rights Reserved. ii Dedication To my parents, Julio César Cruz and Claudia Patricia Duarte. And to Ruth, who has supported me at every step of this long process. I love you all. -

AND YOU WILL KNOW US Mistakes & Regrets .1-2-5 What

... AND YOU WILL KNOW US Mistakes & Regrets .1-2-5 What You Don't Know 10 COMMANDMENTS Not True 1989 100 FLOWERS The Long Arm Of The Social Sciences 100 FLOWERS The Long Arm Of The Social Sciences 100 WATT SMILE Miss You 15 MINUTES Last Chance For You 16 HORSEPOWER 16 Horsepower A&M 540 436 2 CD D 1995 16 HORSEPOWER Sackcloth'n'Ashes PREMAX' TAPESLEEVES PTS 0198 MC A 1996 16 HORSEPOWER Low Estate PREMAX' TAPESLEEVES PTS 0198 MC A 1997 16 HORSEPOWER Clogger 16 HORSEPOWER Cinder Alley 4 PROMILLE Alte Schule 45 GRAVE Insurance From God 45 GRAVE School's Out 4-SKINS One Law For Them 64 SPIDERS Bulemic Saturday 198? 64 SPIDERS There Ain't 198? 99 TALES Baby Out Of Jail A GLOBAL THREAT Cut Ups A GUY CALLED GERALD Humanity A GUY CALLED GERALD Humanity (Funkstörung Remix) A SUBTLE PLAGUE First Street Blues 1997 A SUBTLE PLAGUE Might As Well Get Juiced A SUBTLE PLAGUE Hey Cop A-10 Massive At The Blind School AC 001 12" I 1987 A-10 Bad Karma 1988 AARDVARKS You're My Loving Way AARON NEVILLE Tell It Like It Is ABBA Ring Ring/Rock'n Roll Band POLYDOR 2041 422 7" D 1973 ABBA Waterloo (Swedish version)/Watch Out POLYDOR 2040 117 7" A 1974 ABDELLI Adarghal (The Blind In Spirit) A-BONES Music Minus Five NORTON ED-233 12" US 1993 A-BONES You Can't Beat It ABRISS WEST Kapitalismus tötet ABSOLUTE GREY No Man's Land 1986 ABSOLUTE GREY Broken Promise STRANGE WAYS WAY 101 CD D 1995 ABSOLUTE ZEROS Don't Cry ABSTÜRZENDE BRIEFTAUBEN Das Kriegen Wir schon Hin AU-WEIA SYSTEM 001 12" D 1986 ABSTÜRZENDE BRIEFTAUBEN We Break Together BUCKEL 002 12" D 1987 ABSTÜRZENDE -

Power Structures in V for Vendetta

Master’s Degree programme in European, American and Postcolonial Language and Literature “D.M. 270/2004” Final Thesis Power Structures in V for Vendetta Supervisor Ch. Prof. Shaul Bassi Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. David John Newbold Graduand Valentina Gaio Matriculation Number 858301 Academic Year 2016 / 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE Introduction .....................................................................................................................................1 Graphic Novel as a Form ..............................................................................................................16 V ..........................................................................................................................................23 Adam Susan ...................................................................................................................................34 Evey Hammond ..............................................................................................................................46 Rosemary Almond ..........................................................................................................................56 Helen Heyer ...................................................................................................................................63 Eric Finch ......................................................................................................................................71 Valerie ......................................................................................................................................77