Dark Slivers: Seeing Nirvana in the Shards of Incesticide First Published in Great Britain in 2012 by Running Water Publications, London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

A Denial the Death of Kurt Cobain the Seattle

A DENIAL THE DEATH OF KURT COBAIN THE SEATTLE POLIECE DEPARTMENT’S SUBSTANDARD INVESTIGATION & THE REPROCUSSIONS TO JUSTICE by BREE DONOVAN A Capstone Submitted to The Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University, New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Liberal Studies Under the direction of Dr. Joseph C. Schiavo and approved by _________________________________ Capstone Director _________________________________ Program Director Camden, New Jersey, December 2015 CAPSTONE ABSTRACT A Denial The Death of Kurt Cobain The Seattle Police Department’s Substandard Investigation & The Repercussions to Justice By: BREE DONOVAN Capstone Director: Dr. Joseph C. Schiavo Kurt Cobain (1967-1994) musician, artist songwriter, and founder of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band, Nirvana, was dubbed, “the voice of a generation”; a moniker he wore like his faded cardigan sweater, but with more than some distain. Cobain’s journey to the top of the Billboard charts was much more Dickensian than many of the generations of fans may realize. During his all too short life, Cobain struggled with physical illness, poverty, undiagnosed depression, a broken family, and the crippling isolation and loneliness brought on by drug addiction. Cobain may have shunned the idea of fame and fortune but like many struggling young musicians (who would become his peers) coming up in the blue collar, working class suburbs of Aberdeen and Tacoma Washington State, being ii on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine wasn’t a nightmare image. Cobain, with his unkempt blond hair, polarizing blue eyes, and fragile appearance is a modern-punk-rock Jesus; a model example of the modern-day hero. -

Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home

WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER A) Identification Historic Name: Cobain, Donald & Wendy, House Common Name: Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home Address: 1210 E. First Street City: Aberdeen County: Grays Harbor B) Site Access (describe site access, restrictions, etc.) The nominated home is located mid block near the NW corner of E 1st Street and Chicago Avenue in Aberdeen. The home faces southeast one block from the Wishkah River adjacent to an alleyway. C) Property owner(s), Address and Zip Name: Side One LLC. Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City: Ocean Shores State: WA Zip: 98569 D) Legal boundary description and boundary justification Tax No./Parcel: 015000701700 - 11 - Residential - Single Family Boundary Justification: FRANCES LOT 17 BLK 7 / MAP 1709-04 FORM PREPARED BY Name: Lee & Danielle Bacon Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City / State / Zip: Ocean Shores, WA 98569 Phone: 425.283.2533 Email: [email protected] Nomination June 2021 Date: 1 WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER E) Category of Property (Choose One) building structure (irrigation system, bridge, etc.) district object (statue, grave marker, vessel, etc.) cemetery/burial site historic site (site of an important event) archaeological site traditional cultural property (spiritual or creation site, etc.) cultural landscape (habitation, agricultural, industrial, recreational, etc.) F) Area of Significance – Check as many as apply The property belongs to the early settlement, commercial development, or original native occupation of a community or region. The property is directly connected to a movement, organization, institution, religion, or club which served as a focal point for a community or group. -

A Case Study of Kurt Donald Cobain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) A CASE STUDY OF KURT DONALD COBAIN By Candice Belinda Pieterse Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University December 2009 Supervisor: Prof. J.G. Howcroft Co-Supervisor: Dr. L. Stroud i DECLARATION BY THE STUDENT I, Candice Belinda Pieterse, Student Number 204009308, for the qualification Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology, hereby declares that: In accordance with the Rule G4.6.3, the above-mentioned treatise is my own work and has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. Signature: …………………………………. Date: …………………………………. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several individuals that I would like to acknowledge and thank for all their support, encouragement and guidance whilst completing the study: Professor Howcroft and Doctor Stroud, as supervisors of the study, for all their help, guidance and support. As I was in Bloemfontein, they were still available to meet all my needs and concerns, and contribute to the quality of the study. My parents and Michelle Wilmot for all their support, encouragement and financial help, allowing me to further my academic career and allowing me to meet all my needs regarding the completion of the study. The participants and friends who were willing to take time out of their schedules and contribute to the nature of this study. Konesh Pillay, my friend and colleague, for her continuous support and liaison regarding the completion of this study. -

A Denial the Death of Kurt Cobain the Seattle Police Department

A Denial The Death of Kurt Cobain The Seattle Police Department Substandard Investigation & The Repercussions to Justice by Bree Donovan A Capstone Submitted to The Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University, New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Liberal Studies Under the direction of Dr. Joseph C. Schiavo and approved by _________________________________ Capstone Director _________________________________ Program Director Camden, New Jersey, December 2014 i Abstract Kurt Cobain (1967-1994) musician, artist songwriter, and founder of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band, Nirvana, was dubbed, “the voice of a generation”; a moniker he wore like his faded cardigan sweater, but with more than some distain. Cobain‟s journey to the top of the Billboard charts was much more Dickensian than many of the generations of fans may realize. During his all too short life, Cobain struggled with physical illness, poverty, undiagnosed depression, a broken family, and the crippling isolation and loneliness brought on by drug addiction. Cobain may have shunned the idea of fame and fortune but like many struggling young musicians (who would become his peers) coming up in the blue collar, working class suburbs of Aberdeen and Tacoma Washington State, being on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine wasn‟t a nightmare image. Cobain, with his unkempt blond hair, polarizing blue eyes, and fragile appearance is a modern-punk-rock Jesus; a model example of the modern-day hero. The musician- a reluctant hero at best, but one who took a dark, frightening journey into another realm, to emerge stronger, clearer headed and changing the trajectory of his life. -

Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck Pdf, Epub, Ebook

KURT COBAIN: MONTAGE OF HECK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Brett Morgen | 160 pages | 05 May 2015 | Insight Editions, Div of Palace Publishing Group, LP | 9781608875498 | English | San Rafael, United States Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck PDF Book You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck makes a persuasive case for its subject without resorting to hagiography -- and includes plenty of rare and unreleased footage for fans. Sign In. Rolling Stone. After Kurt Cobain is born in , his parents move to Aberdeen, Washington and shortly after his sister Kim is born. Kurt Cobain. Archived from the original on November 19, Book Category. After recording their next album, Nevermind , their song " Smells Like Teen Spirit " becomes a hit and the band is launched into the mainstream. Kurt Cobain: Montage Of Heck After a short while, Kurt breaks up with Tracy. Bleach Nevermind In Utero. Helen Razer. Nevertheless, Kyle Anderson of Entertainment Weekly praised the album, considering it as "a cultural artifact that provides an inside look at the creative process of an enigmatic genius. Cobain's mother, Wendy, had regret in relation to working on the film. Archived from the original on February 6, We would have known that story. Downloads Wrong links Broken links Missing download Add new mirror links. We get a very intimate glimpse of the beloved musician from his early years all the way up to , when he tragically took his own life at the age of After he attempts to have sex with the girl, his classmates begin insulting and shaming him. -

Coming up at the Aquarium Tickets at Dempsey's, Orange Records and Ticketweb.Com • 21+ Upstairs at 226 Broadway in Fargo • Online at Aquariumfargo.Com

COMING UP AT THE AQUARIUM TICKETS AT DEMPSEY'S, ORANGE RECORDS AND TICKETWEB.COM • 21+ UPSTAIRS AT 226 BROADWAY IN FARGO • ONLINE AT AQUARIUMFARGO.COM SIMON JOYNER & THE GHOSTS • THURSDAY, JUNE 6 MAUNO • MONDAY, JUNE 24 Lo-fi folk cited as an influence by Conor Oberst, Idiosyncratic, tumbling indie pop w/ plumslugger, Gillian Welch, Kevin Morby and Beck w/ Parliament Lite and Bryan Stanley (First show! Richard Loewen and Walker Rider • Doors @ 8 Backed by members of Naivety ) • Doors @ 8 MUSCLE BEACH + MCVICKER • FRIDAY, JUNE 7 ROYAL TUSK • THURSDAY, JUNE 27 A double dose of noisy Minneapolis Blue-collar troubadours merging riffy hooks punk rock n roll w/ locals Under Siege, with a thick bottom end and loud-as-hell guitars Plumslugger and HomeState • Doors @ 9 w/ The Dose • Jade Presents event • Doors @ 7 EMO NIGHT • SATURDAY, JUNE 8 MEGAN HAMILTON • FRIDAY, JUNE 28 Drink some drinks, dance, hang out and have Funky house tunes w/ SLiPPERS, Force Induction, some fun singing along to all your favorite early DeziLou, 2Clapz and Alex Malard • Playback 2000s emo jams • No cover • Starts @ 10 Shows + Wicked Good Time event • Doors @ 9 PAPER PARLOR + STOVEPIPES • SUNDAY, JUNE 9 JESSICA VINES + KARI MARIE TRIO • SATURDAY, JUNE 29 Psychedelic blues fusion jam rockers Guitar-driven, poppy, funky, rockin’ R&B + piano comin' in hot from Duluth + local blues rock from members of The Human Element and rock favorites Stovepipes • Doors @ 8 Hardwood Groove among others • Doors @ 8 HIP-HOP + COMEDY NIGHT • FRIDAY, JUNE 14 YATRA + GREEN ALTAR • SUNDAY, JUNE 30 Music by Durow, X3P Suicide, Stan Cass and Stoner, sludge and doom metal from Baltimore and DJ Affilination. -

Nirvana in Utero Album Download

nirvana in utero album download Nirvana – In Utero (1993) This 20th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition of the unwitting swansong of the single most influential band of the 1990s features more than 70 remastered, remixed, rare and unreleased recordings, including B-sides, compilation tracks, never-before-heard demos and live material featuring the final touring lineup of Cobain, Novoselic, Grohl, and Pat Smear. Additional Info: • Released Date: September 24, 2013 • More Info Hi-Res. Disc 1: Original Album Remastered 01. Serve The Servants (Album Version) – 03:37 02. Scentless Apprentice (Album Version) – 03:48 03. Heart-Shaped Box (Album Version) – 04:41 04. Rape Me (Album Version) – 02:50 05. Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge On Seattle (Album Version) – 04:10 06. Dumb (Album Version) – 02:32 07. Very Ape (Album Version) – 01:56 08. Milk It (Album Version) – 03:55 09. Pennyroyal Tea (Album Version) – 03:39 10. Radio Friendly Unit Shifter (Album Version) – 04:52 11. Tourette’s (Album Version) – 01:35 12. All Apologies (Album Version) – 03:56 B-Sides & Bonus Tracks 13. Gallons Of Rubbing Alcohol Flow Through The Strip (Album Version) – 07:34 14. Marigold (B-Side) – 02:34 15. Moist Vagina (2013 Mix) – 03:34 16. Sappy (2013 Mix) – 03:26 17. I Hate Myself And Want To Die (2013 Mix) – 03:00 18. Pennyroyal Tea (Scott Litt Mix) – 03:36 19. Heart Shaped Box (Original Steve Albini 1993 Mix) – 04:42 20. All Apologies (Original Steve Albini 1993 Mix) – 03:52. Disc 2: Original Album 2013 Mix 01. Serve The Servants (2013 Mix) – 03:38 02. -

ACR Manual on Contrast Media

ACR Manual On Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media Preface 2 ACR Manual on Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media © Copyright 2021 American College of Radiology ISBN: 978-1-55903-012-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page 1. Preface 1 2. Version History 2 3. Introduction 4 4. Patient Selection and Preparation Strategies Before Contrast 5 Medium Administration 5. Fasting Prior to Intravascular Contrast Media Administration 14 6. Safe Injection of Contrast Media 15 7. Extravasation of Contrast Media 18 8. Allergic-Like And Physiologic Reactions to Intravascular 22 Iodinated Contrast Media 9. Contrast Media Warming 29 10. Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury and Contrast 33 Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Adults 11. Metformin 45 12. Contrast Media in Children 48 13. Gastrointestinal (GI) Contrast Media in Adults: Indications and 57 Guidelines 14. ACR–ASNR Position Statement On the Use of Gadolinium 78 Contrast Agents 15. Adverse Reactions To Gadolinium-Based Contrast Media 79 16. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) 83 17. Ultrasound Contrast Media 92 18. Treatment of Contrast Reactions 95 19. Administration of Contrast Media to Pregnant or Potentially 97 Pregnant Patients 20. Administration of Contrast Media to Women Who are Breast- 101 Feeding Table 1 – Categories Of Acute Reactions 103 Table 2 – Treatment Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 105 Children Table 3 – Management Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 114 Adults Table 4 – Equipment For Contrast Reaction Kits In Radiology 122 Appendix A – Contrast Media Specifications 124 PREFACE This edition of the ACR Manual on Contrast Media replaces all earlier editions. -

Smells Like Teen Spirit Appears in Rock & Pop 2018

ACCESS ALL AREAS... SMELLS LIKE TEEN SPIRIT APPEARS IN ROCK & POP 2018 Released: 1991 Album: Nevermind Label: DGC Records ABOUT THE SONG Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain was attempting to write the ‘ultimate pop song’ when he came up with the guitar riff that would become ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’. He WITH THE LIGHTS OUT, wanted to write a song in the style of The Pixies, telling Rolling Stone in 1994: ‘I was basically trying to rip off The Pixies. I have to admit it.’ The title came IT’S LESS DANGEROUS after Kathleen Hanna, lead singer of Bikini Kill, spray- painted ‘Kurt smells like Teen Spirit’ on his bedroom “ wall. Teen Spirit was actually a brand of deodorant. HERE WE ARE NOW, The first single from Nirvana’s second album Nevermind, ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ was a surprise hit. The label had anticipated that ‘Come As You Are’, the follow-up single, would be the song to cross over to a mainstream audience. ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ ENTERTAIN US was first played on college radio before rock stations and MTV picked it up. It is widely praised as one of I FEEL STUPID AND CONTAGIOUS the greatest songs in the history of rock music. RECORDING AND PRODUCTION Cobain began writing ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ a few weeks before Nirvana were due in the studio to record Nevermind. After presenting the main riff and melody of the chorus to the rest of the band, they jammed around the riff for an hour and a half. Bassist Krist Novoselic slowed the verse down and drummer Dave Grohl created a drum beat and as a result, ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ is the only song on Nevermind to give songwriting credits to all three band members. -

Krist Novoselic

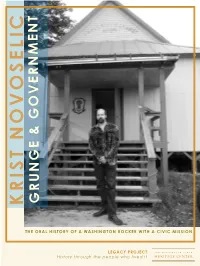

OVERNMENT G & E GRUNG KRIST NOVOSELIC THE ORAL HISTORY OF A WASHINGTON ROCKER WITH A CIVIC MISSION LEGACY PROJECT History through the people who lived it Krist Novoselic Research by John Hughes and Lori Larson Transcripti on by Lori Larson Interviews by John Hughes October 14, 2008 John Hughes: This is October 14, 2008. I’m John Hughes, Chief Oral Historian for the Washington State Legacy Project, with the Offi ce of the Secretary of State. We’re in Deep River, Wash., at the home of Krist Novoselic, a 1984 graduate of Aberdeen High School; a founding member of the band Nirvana with his good friend Kurt Cobain; politi cal acti vist, chairman of the Wahkiakum County Democrati c Party, author, fi lmmaker, photographer, blogger, part-ti me radio host, While doing reseach at the State Archives in 2005, Novoselic volunteer disc jockey, worthy master of the Grays points to Grays River in Wahkiakum County, where he lives. Courtesy Washington State Archives River Grange, gentleman farmer, private pilot, former commercial painter, ex-fast food worker, proud son of Croati a, and an amateur Volkswagen mechanic. Does that prett y well cover it, Krist? Novoselic: And chairman of FairVote to change our democracy. Hughes: You know if you ever decide to run for politi cal offi ce, your life is prett y much an open book. And half of it’s on YouTube, like when you tried for the Guinness Book of World Records bass toss on stage with Nirvana and it hits you on the head, and then Kurt (Cobain) kicked you in the butt . -

AUDIO + VIDEO 9/14/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to Be Taken Directly to the Sell Sheet

NEW RELEASES WEA.COM ISSUE 18 SEPTEMBER 14 + SEPTEMBER 21, 2010 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word AUDIO + VIDEO 9/14/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date DV- En Vivo Desde Morelia 15 LAT 525832 BANDA MACHOS Años (DVD) $12.99 9/14/10 8/18/10 CD- FER 888109 BARLOWGIRL Our Journey…So Far $11.99 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- NON 524138 CHATHAM, RHYS A Crimson Grail $16.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- ATL 524647 CHROMEO Business Casual $13.99 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- Business Casual (Deluxe ATL 524649 CHROMEO Edition) $18.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 Business Casual (White ATL A-524647 CHROMEO Colored Vinyl) $18.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 DV- Crossroads Guitar Festival RVW 525705 CLAPTON, ERIC 2004 (Super Jewel)(2DVD) $29.99 9/14/10 8/18/10 DV- Crossroads Guitar Festival RVW 525708 CLAPTON, ERIC 2007 (Super Jewel)(2DVD) $29.99 9/14/10 8/18/10 COLMAN, Shape Of Jazz To Come (180 ACG A-1317 ORNETTE Gram Vinyl) $24.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 REP A-524901 DEFTONES White Pony (2LP) $26.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- RRR 177622 DRAGONFORCE Twilight Dementia (Live) $18.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 DV- LAT 525829 EL TRI Sinfonico (DVD) $12.99 9/14/10 8/18/10 JACKSON, MILT & HAWKINS, ACG A-1316 COLEMAN Bean Bags (180 Gram Vinyl) $24.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- NON 287228 KREMER, GIDON