Black Budgets: the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Chislett

ANTI-AMERICANISM IN SPAIN: THE WEIGHT OF HISTORY William Chislett Working Paper (WP) 47/2005 18/11/2005 Area: US-Transatlantic Dialogue – WP Nº 47/2005 18/11/2005 Anti-Americanism in Spain: The Weight of History William Chislett ∗ Summary: Spain’s feelings toward the United States are the coldest in Europe after Turkey, according to a poll by the German Marshall Fund. And they have been that way for a very long time. The country’s thermometer reading on a scale of 0-100 was 42º in 2005, only surpassed by Turkey’s 28º and compared with an average of 50º for the 10 countries surveyed (see Figure 1). The same degree of coldness towards the United States was brought out in the 16-country Pew Global Attitudes Project where only 41% of Spaniards said they had a very or somewhat favourable view of the United States. This surprises many people. After all, Spain has become a vibrant democracy and a successful market economy since the right-wing dictatorship of General Franco ended in 1975 with the death of the Generalísimo. Why are Spaniards so cool towards the United States? Spain’s feelings toward the United States are the coldest in Europe after Turkey, according to a poll by the German Marshall Fund. And they have been that way for a very long time. The country’s thermometer reading on a scale of 0-100 was 42º in 2005, only surpassed by Turkey’s 28º and compared with an average of 50º for the 10 countries surveyed (see Figure 1). -

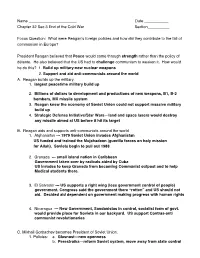

Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section___Focus Question

Name ______________________ Date ___________ Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section__________ Focus Question: What were Reaganʼs foreign policies and how did they contribute to the fall of communism in Europe? President Reagan believed that Peace would come through strength rather than the policy of détente. He also believed that the US had to challenge communism to weaken it. How would he do this? 1. Build up military-new nuclear weapons 2. Support and aid anti-communists around the world A. Reagan builds up the military. 1. largest peacetime military build up 2. Billions of dollars to development and productions of new weapons, B1, B-2 bombers, MX missile system 3. Reagan knew the economy of Soviet Union could not support massive military build up 4. Strategic Defense Initiative/Star Wars—land and space lasers would destroy any missile aimed at US before it hit its target B. Reagan aids and supports anti-communists around the world 1. Afghanistan --- 1979 Soviet Union invades Afghanistan US funded and trained the Mujahadeen (guerilla forces on holy mission for Allah). Soviets begin to pull out 1988 2. Grenada --- small island nation in Caribbean Government taken over by radicals aided by Cuba US invades to keep Granada from becoming Communist outpost and to help Medical students there. 3. El Salvador --- US supports a right wing (less government control of people) government. Congress said the government there “rotten” and US should not aid. Decided aid dependent on government making progress with human rights 4. Nicaragua --- New Government, Sandanistas in control, socialist form of govt. -

The Anti-Contra-War Campaign: Organizational Dynamics of a Decentralized Movement

International Journal of Peace Studies, Volume 13, Number 1, Spring/Summer 2008 THE ANTI-CONTRA-WAR CAMPAIGN: ORGANIZATIONAL DYNAMICS OF A DECENTRALIZED MOVEMENT Roger Peace Abstract This essay examines the nature and organizational dynamics of the anti-Contra-war campaign in the United States. Lasting from 1982 to 1990, this anti-interventionist movement sought to halt the U.S.- backed guerrilla war against the Sandinista government of Nicaragua. The forces pulling the anti- Contra-war campaign (ACWC) together and pulling it apart are analyzed. The essay is comprised of four parts: 1) overview of the Contra war and the ACWC; 2) the major activist networks involved in the ACWC, 3) the development of common political goals and educational themes; and 4) the national coordination of activities—lobbying, educational outreach, protests, and transnational activities. The final section addresses the significance of the ACWC from an historical perspective. Introduction The U.S.-directed Contra war against Sandinista Nicaragua in the 1980s sparked an anti-interventionist campaign that involved over one thousand U.S. peace and justice organizations (Central America Resource Center, 1987). The anti-Contra-war campaign (ACWC) was part of a vigorous Central America movement that included efforts to halt U.S. aid to the Salvadoran and Guatemalan governments and provide sanctuary for Central American refugees. Scholarly literature on the anti-Contra-war campaign is not extensive. Some scholars have examined the ACWC in the context of the Central America movement (Battista, 2002; Brett, 1991; Gosse, 1988, 1995, 1998; Nepstad, 1997, 2001, 2004; Smith, 1996). Some have concentrated on particular aspects of the ACWC—political influence (Arnson and Brenner, 1993), local organizing in Boston and New Bedford, Massachusetts (Hannon, 1991; Ryan, 1989, 1991), and transnational activities (Kavaloski, 1990; Nepstad, 1996; Nepstad and Smith, 1999; Scallen, 1992). -

Nicaragua and El Salvador

UNIDIR/97/1 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Geneva Disarmament and Conflict Resolution Project Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Nicaragua and El Salvador Papers: Paulo S. Wrobel Questionnaire Analysis: Lt Col Guilherme Theophilo Gaspar de Oliverra Project funded by: the Ford Foundation, the United States Institute of Peace, the Winston Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and the governments of Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Finland, France, Germany, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, South Africa, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 1997 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. UNIDIR/97/1 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. GV.E.97.0.1 ISBN 92-9045-121-1 Table of Contents Page Previous DCR Project Publications............................... v Preface - Sverre Lodgaard ..................................... vii Acknowledgements ...........................................ix Project Introduction - Virginia Gamba ............................xi List of Acronyms........................................... xvii Maps.................................................... xviii Part I: Case Study: Nicaragua .......................... 1 I. Introduction ....................................... 3 II. National Disputes and Regional Crisis .................. 3 III. The Peace Agreement, the Evolution of the Conflicts and the UN Role.................................... 8 1. The Evolution of the Conflict in Nicaragua............ 10 2. -

El Salvador in the 1980S: War by Other Means

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons CIWAG Case Studies 6-2015 El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means Donald R. Hamilton Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ciwag-case-studies Recommended Citation Hamilton, Donald R., "El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means" (2015). CIWAG Case Studies. 5. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ciwag-case-studies/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in CIWAG Case Studies by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Draft as of 121916 ARF R W ARE LA a U nd G A E R R M R I E D n o G R R E O T U N P E S C U N E IT EG ED L S OL TA R C TES NAVAL WA El Salvador in the 1980’s: War by Other Means Donald R. Hamilton United States Naval War College Newport, Rhode Island El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means Donald R. Hamilton HAMILTON: EL SALVADOR IN THE 1980s Center on Irregular Warfare & Armed Groups (CIWAG) US Naval War College, Newport, RI [email protected] This work is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. This case study is available on CIWAG’s public website located at http://www.usnwc.edu/ciwag 2 HAMILTON: EL SALVADOR IN THE 1980s Message from the Editors In 2008, the Naval War College established the Center on Irregular Warfare & Armed Groups (CIWAG). -

Apartheid's Contras: an Inquiry Into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique

Apartheid's Contras: An Inquiry into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp20005 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Apartheid's Contras: An Inquiry into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique Author/Creator Minter, William Publisher Zed Books Ltd, Witwatersrand University Press Date 1994-00-00 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Angola, Mozambique, South Africa, Southern Africa (region) Coverage (temporal) 1975 - 1993 Rights By kind permission of William Minter. Description This book explores the wars in Angola and Mozambique after independence. -

Great Game to 9/11

Air Force Engaging the World Great Game to 9/11 A Concise History of Afghanistan’s International Relations Michael R. Rouland COVER Aerial view of a village in Farah Province, Afghanistan. Photo (2009) by MSst. Tracy L. DeMarco, USAF. Department of Defense. Great Game to 9/11 A Concise History of Afghanistan’s International Relations Michael R. Rouland Washington, D.C. 2014 ENGAGING THE WORLD The ENGAGING THE WORLD series focuses on U.S. involvement around the globe, primarily in the post-Cold War period. It includes peacekeeping and humanitarian missions as well as Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom—all missions in which the U.S. Air Force has been integrally involved. It will also document developments within the Air Force and the Department of Defense. GREAT GAME TO 9/11 GREAT GAME TO 9/11 was initially begun as an introduction for a larger work on U.S./coalition involvement in Afghanistan. It provides essential information for an understanding of how this isolated country has, over centuries, become a battleground for world powers. Although an overview, this study draws on primary- source material to present a detailed examination of U.S.-Afghan relations prior to Operation Enduring Freedom. Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government. Cleared for public release. Contents INTRODUCTION The Razor’s Edge 1 ONE Origins of the Afghan State, the Great Game, and Afghan Nationalism 5 TWO Stasis and Modernization 15 THREE Early Relations with the United States 27 FOUR Afghanistan’s Soviet Shift and the U.S. -

Washington's Foundering Fathers: the Contras and Contragate

AUSTRALIAN LEFT REVIEW 31 WASHINGTON'S FOUNDERING FATHERS The Contras and Contragate Barry Carr Contragate revealed the depth of Washington's commitment to the Contras. But it hasn't made life any easier for Nicaragua. here is no issue closer to the footsteps of the Founding Fathers of million) to the Contras, Reagan heart of the Reagan administ the United States, and has likened commented "I'm sure it put a smile T ration than its crusade against them to Simon Bolivar, the French on the face ofthe Statue ofLiberty".1 the Sandinista government of Resistance and, most recently and Nicaragua. President Reagan is bizarrely, the Abratlam Lincoln Support for the Nicaraguan completely besotted with the Brigade of the Spanish Civil War. counter-revolution is the best Contras. He has described them as When the US Co!!gress finall3 voted, example of the US's grotesque efforts freedom fighters following in the in JuJy 1986, to renew aid ($100 at "symmetry" - i.e. the attempt to AUSTRALIAN LEFT REVIEW 33 mtmtc and counter the Soviet Union's alleged instigation of national liberation movements by fomenting anti-communist insurgencies in regions of the world where US hegemony is threatened by nationalist and socialist states. The Contras emerged from the ranks of the hated National Guard who fled to Honduras and Costa Rica following on the fall of the Somoza dynasty in 1979. The bedraggled and demoralised Somocistas in Honduras were reorganised by the CIA during 1981, receiving $19 million in US government funds, and training from Argentine military advisers who had been blooded in the ferocious "dirty war" of 1976-81 in which 25-30,000 Argentine civilians were murdered. -

The Battle for Pakistan

ebooksall.com ebooksall.com ebooksall.com SHUJA NAWAZ THE BATTLE F OR PAKISTAN The Bitter US Friendship and a Tough Neighbourhood PENGUIN BOOKS ebooksall.com Contents Important Milestones 2007–19 Abbreviations and Acronyms Preface: Salvaging a Misalliance 1. The Revenge of Democracy? 2. Friends or Frenemies? 3. 2011: A Most Horrible Year! 4. From Tora Bora to Pathan Gali 5. Internal Battles 6. Salala: Anatomy of a Failed Alliance 7. Mismanaging the Civil–Military Relationship 8. US Aid: Leverage or a Trap? 9. Mil-to-Mil Relations: Do More 10. Standing in the Right Corner 11. Transforming the Pakistan Army 12. Pakistan’s Military Dilemma 13. Choices Footnotes Important Milestones 2007–19 Preface: Salvaging a Misalliance 1. The Revenge of Democracy? 2. Friends or Frenemies? 3. 2011: A Most Horrible Year! 4. From Tora Bora to Pathan Gali 5. Internal Battles 6. Salala: Anatomy of a Failed Alliance 7. Mismanaging the Civil–Military Relationship 8. US Aid: Leverage or a Trap? 9. Mil-to-Mil Relations: Do More 10. Standing in the Right Corner 11. Transforming the Pakistan Army 12. Pakistan’s Military Dilemma 13. Choices Select Bibliography ebooksall.com Acknowledgements Follow Penguin Copyright ebooksall.com Advance Praise for the Book ‘An intriguing, comprehensive and compassionate analysis of the dysfunctional relationship between the United States and Pakistan by the premier expert on the Pakistan Army. Shuja Nawaz exposes the misconceptions and contradictions on both sides of one of the most crucial bilateral relations in the world’ —BRUCE RIEDEL, senior fellow and director of the Brookings Intelligence Project, and author of Deadly Embrace: Pakistan, America and the Future of the Global Jihad ‘A superb, thoroughly researched account of the complex dynamics that have defined the internal and external realities of Pakistan over the past dozen years. -

Research Paper N°12 August 2014

Centre Français de Recherche sur le Renseignement OPERATION CYCLONE AND ITS CONSEQUENCES Research Paper n°12 August 2014 21 boulevard Haussmann, 75009 Paris - France Tél. : 33 1 53 43 92 44 Fax : 33 1 53 43 92 92 www.cf2r.org Association régie par la loi du 1er juillet 1901 SIRET n° 453 441 602 000 19 ! Centre!Français!de!Recherche!sur!le!Renseignement! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! OPERATION!CYCLONE! AND!ITS!CONSEQUENCES! % % % ! ! Dr%FARHAN%ZAHID%% % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Research!Paper!n°12!<!August!2014! _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________% 21%Boulevard%Haussmann,%75009%Paris%<%France% Tél.%:%33%1%53%43%92%44%%%%%Fax%:%33%1%53%43%92%92%%%%%www.cF2r.orG% Association%réGie%par%la%loi%du%1er%juillet%1901%%%%%SIRET%n°%453%441%602%000%19% % 2 ! ! ! ! PRESENTATION%OF% % ! ! ! ! Founded!in!2000,!the!FRENCH!CENTRE!FOR!INTELLIGENCE!RESEARCH!(CF2R)! is! an! independent! Think& Tank,! regulated! by! the! French! Association! Law! of! 1901,! and! specialised! in! the! study! of! intelligence! and! international! security.! Its! missions! are! as! follows:! M! development! of! academic! research! and! publications! on! intelligence! and! international!security,! M!provision!of!expertise!for!public!policy!stakeholders!(decisionMmakers,!government,! lawmakers,!media,!etc.),! M!dispelling!of!myths!surrounding!intelligence!and!explaining!the!role!of!intelligence! to!the!general!public.! ! ! !%ORGANISATION% ! ! The! FRENCH! CENTER! FOR! INTELLIGENCE! RESEARCH! (CF2R)! -

Conflict and Disease an Analysis of Endem Ic Polio in Northern Pakistan

CONFLICT AND DISEASE AN ANALYSIS OF ENDEM IC POLIO IN NORTHERN PAKISTAN Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy Capstone Project Submitted by Randall Quinn December 15, 2015 © 2015 Quinn http://fletcher.tufts.edu Quinn The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy Conflict and Disease An Analysis of Endemic Polio in Northern Pakistan Randall M Quinn Graduate Thesis 12-15-2015 1 Conflict and Disease Quinn Abstract Polio is a disease that held a profound impact on much of the world’s population for the first half of the 20th Century. Today it is barely an afterthought throughout the developed world, as vaccines invented in the 1950’s greatly reduced the disease burden, gradually at first and then precipitously with the onset of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative in 1988. Despite great progress, there is one remaining reservoir of wild poliovirus that remains in the world today and prevents any declaration of victory against the disease. The reservoir is centered in northern Pakistan and frequently infects populations on both sides of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border. A number of factors have contributed to this being the last global holdout. This paper aims to explore those factors and project potential policy solutions. Given the highly infectious nature of the disease and the frequent movement of people in and through this region, all of the elements are there for a global resurgence, highlighting the importance of resolving the issue as quickly and efficiently as possible. 2 Conflict and Disease Quinn Table of Contents Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................... -

Zbigniew Brzezinski's Narrative for the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2019 "Excellent Propaganda" Zbigniew Brzezinski's Narrative for the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan Matt Mulhern CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/786 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Excellent Propaganda” Zbigniew Brzezinski’s Narrative for the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan Matt Mulhern B.F.A. Rutgers University, 1982 Thesis Advisor – Craig Daigle, PhD Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York Thesis Research B9900 December 10, 2019 1 2 The series of regime changes in Kabul that resulted in the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December of 1979 is a story of poor intelligence, false narratives, and missed opportunities to avoid conflict for both the Soviet Union and the United States. When a small faction of Afghan communists overthrew the government of Mohammed Daoud Khan and replaced him with Nur Muhammad Taraki on April 30, 1978, the United States and the Soviet Union embarked on a path of mutual suspicion and lack of trust that led to an American involvement in Afghanistan that is ongoing – forty years later. As the architect of the American response from its very beginning, Zbigniew Brzezinski, President Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor, bears responsibility for much of what happened.