William Chislett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section___Focus Question

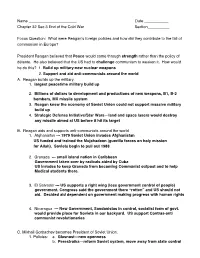

Name ______________________ Date ___________ Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section__________ Focus Question: What were Reaganʼs foreign policies and how did they contribute to the fall of communism in Europe? President Reagan believed that Peace would come through strength rather than the policy of détente. He also believed that the US had to challenge communism to weaken it. How would he do this? 1. Build up military-new nuclear weapons 2. Support and aid anti-communists around the world A. Reagan builds up the military. 1. largest peacetime military build up 2. Billions of dollars to development and productions of new weapons, B1, B-2 bombers, MX missile system 3. Reagan knew the economy of Soviet Union could not support massive military build up 4. Strategic Defense Initiative/Star Wars—land and space lasers would destroy any missile aimed at US before it hit its target B. Reagan aids and supports anti-communists around the world 1. Afghanistan --- 1979 Soviet Union invades Afghanistan US funded and trained the Mujahadeen (guerilla forces on holy mission for Allah). Soviets begin to pull out 1988 2. Grenada --- small island nation in Caribbean Government taken over by radicals aided by Cuba US invades to keep Granada from becoming Communist outpost and to help Medical students there. 3. El Salvador --- US supports a right wing (less government control of people) government. Congress said the government there “rotten” and US should not aid. Decided aid dependent on government making progress with human rights 4. Nicaragua --- New Government, Sandanistas in control, socialist form of govt. -

The United Nations' Political Aversion to the European Microstates

UN-WELCOME: The United Nations’ Political Aversion to the European Microstates -- A Thesis -- Submitted to the University of Michigan, in partial fulfillment for the degree of HONORS BACHELOR OF ARTS Department Of Political Science Stephen R. Snyder MARCH 2010 “Elephants… hate the mouse worst of living creatures, and if they see one merely touch the fodder placed in their stall they refuse it with disgust.” -Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, 77 AD Acknowledgments Though only one name can appear on the author’s line, there are many people whose support and help made this thesis possible and without whom, I would be nowhere. First, I must thank my family. As a child, my mother and father would try to stump me with a difficult math and geography question before tucking me into bed each night (and a few times they succeeded!). Thank you for giving birth to my fascination in all things international. Without you, none of this would have been possible. Second, I must thank a set of distinguished professors. Professor Mika LaVaque-Manty, thank you for giving me a chance to prove myself, even though I was a sophomore and studying abroad did not fit with the traditional path of thesis writers; thank you again for encouraging us all to think outside the box. My adviser, Professor Jenna Bednar, thank you for your enthusiastic interest in my thesis and having the vision to see what needed to be accentuated to pull a strong thesis out from the weeds. Professor Andrei Markovits, thank you for your commitment to your students’ work; I still believe in those words of the Moroccan scholar and will always appreciate your frank advice. -

The Anti-Contra-War Campaign: Organizational Dynamics of a Decentralized Movement

International Journal of Peace Studies, Volume 13, Number 1, Spring/Summer 2008 THE ANTI-CONTRA-WAR CAMPAIGN: ORGANIZATIONAL DYNAMICS OF A DECENTRALIZED MOVEMENT Roger Peace Abstract This essay examines the nature and organizational dynamics of the anti-Contra-war campaign in the United States. Lasting from 1982 to 1990, this anti-interventionist movement sought to halt the U.S.- backed guerrilla war against the Sandinista government of Nicaragua. The forces pulling the anti- Contra-war campaign (ACWC) together and pulling it apart are analyzed. The essay is comprised of four parts: 1) overview of the Contra war and the ACWC; 2) the major activist networks involved in the ACWC, 3) the development of common political goals and educational themes; and 4) the national coordination of activities—lobbying, educational outreach, protests, and transnational activities. The final section addresses the significance of the ACWC from an historical perspective. Introduction The U.S.-directed Contra war against Sandinista Nicaragua in the 1980s sparked an anti-interventionist campaign that involved over one thousand U.S. peace and justice organizations (Central America Resource Center, 1987). The anti-Contra-war campaign (ACWC) was part of a vigorous Central America movement that included efforts to halt U.S. aid to the Salvadoran and Guatemalan governments and provide sanctuary for Central American refugees. Scholarly literature on the anti-Contra-war campaign is not extensive. Some scholars have examined the ACWC in the context of the Central America movement (Battista, 2002; Brett, 1991; Gosse, 1988, 1995, 1998; Nepstad, 1997, 2001, 2004; Smith, 1996). Some have concentrated on particular aspects of the ACWC—political influence (Arnson and Brenner, 1993), local organizing in Boston and New Bedford, Massachusetts (Hannon, 1991; Ryan, 1989, 1991), and transnational activities (Kavaloski, 1990; Nepstad, 1996; Nepstad and Smith, 1999; Scallen, 1992). -

Cuba Tightens Foreign-Exchange Rules As Alimport Continues to Buy U.S

Vol. 13, No. 1 January 2005 www.cubanews.com In the News Cuba tightens foreign-exchange rules Adios, free zones? as Alimport continues to buy U.S. food Government says Cuba’s zonas francas do BY TRACEY EATON “Families can barely feed themselves, and not create enough jobs .................Page 3 uban President Fidel Castro summed up there is little room for luxuries like children’s 2004 like this: “There couldn’t have been toys or a night out with the family,” said James Offshore bonanza C a worse year, and there couldn’t have Cason, the top U.S. diplomat in Cuba. “Castro is been a better year, either.” determined to remain on the wrong side of his- Sherritt, Pebercan strike oil near Santa Two hurricanes, a stubborn drought, spiral- tory, while Cubans wait for his strange and Cruz del Norte ...............................Page 4 ing energy costs and stepped-up U.S. sanctions unsuccessful experiment to come to an end.” hammered the economy. But Castro supporters Undaunted, Castro celebrated his 46th year in Uruguayan friends say Cuba survived and even moved forward. power on New Year’s Day. He has outlasted nine The economy grew at a rate of 5%, and unem- American presidents and is working on his 10th. Tabaré Vázquez vows to restore full dip- ployment dropped to 2%. A reserve containing He is the longest-ruling head of government on the planet. lomatic relations with Havana ......Page 6 up to 100 million barrels of oil was discovered off the northern coast (see page 4). “He’s a tough old bird,” said a veteran foreign And in late December, Castro delivered some journalist, stunned to see the Cuban leader Caracas connection remarkable news, saying for the first time that walking in public the other day just two months Venezuela, Cuba sign sweeping free-trade the island was finally emerging from the “Spe- after he shattered his kneecap in a fall televised around the world. -

Nicaragua and El Salvador

UNIDIR/97/1 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Geneva Disarmament and Conflict Resolution Project Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Nicaragua and El Salvador Papers: Paulo S. Wrobel Questionnaire Analysis: Lt Col Guilherme Theophilo Gaspar de Oliverra Project funded by: the Ford Foundation, the United States Institute of Peace, the Winston Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and the governments of Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Finland, France, Germany, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, South Africa, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 1997 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. UNIDIR/97/1 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. GV.E.97.0.1 ISBN 92-9045-121-1 Table of Contents Page Previous DCR Project Publications............................... v Preface - Sverre Lodgaard ..................................... vii Acknowledgements ...........................................ix Project Introduction - Virginia Gamba ............................xi List of Acronyms........................................... xvii Maps.................................................... xviii Part I: Case Study: Nicaragua .......................... 1 I. Introduction ....................................... 3 II. National Disputes and Regional Crisis .................. 3 III. The Peace Agreement, the Evolution of the Conflicts and the UN Role.................................... 8 1. The Evolution of the Conflict in Nicaragua............ 10 2. -

El Salvador in the 1980S: War by Other Means

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons CIWAG Case Studies 6-2015 El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means Donald R. Hamilton Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ciwag-case-studies Recommended Citation Hamilton, Donald R., "El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means" (2015). CIWAG Case Studies. 5. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ciwag-case-studies/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in CIWAG Case Studies by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Draft as of 121916 ARF R W ARE LA a U nd G A E R R M R I E D n o G R R E O T U N P E S C U N E IT EG ED L S OL TA R C TES NAVAL WA El Salvador in the 1980’s: War by Other Means Donald R. Hamilton United States Naval War College Newport, Rhode Island El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means Donald R. Hamilton HAMILTON: EL SALVADOR IN THE 1980s Center on Irregular Warfare & Armed Groups (CIWAG) US Naval War College, Newport, RI [email protected] This work is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. This case study is available on CIWAG’s public website located at http://www.usnwc.edu/ciwag 2 HAMILTON: EL SALVADOR IN THE 1980s Message from the Editors In 2008, the Naval War College established the Center on Irregular Warfare & Armed Groups (CIWAG). -

Justice in Times of Transition: Lessons from the Iberian Experience

Center for European Studies Working Paper Series #173 (2009) Justice in Times of Transition: Lessons from the Iberian Experience Omar G. Encarnación Professor and Chair of Political Studies Bard College Division of Social Studies Annandale-on-Hudson, New York 12504 E-mail – [email protected] Abstract A key contention of the transitional justice movement is that the more comprehensive and vigorous the effort to bring justice to a departed authoritarian regime the better the democratizing outcome will be. This essay challenges this view with empirical evidence from the Iberian Peninsula. In Portugal, a sweeping policy of purges intended to cleanse the state and society of the authoritarian past nearly derailed the transition to democracy by descending into a veritable witch-hunt. In Spain, by contrast, letting bygones be bygones, became a foundation for democratic consolidation. These counter-intuitive examples suggest that there is no pre-ordained outcome to transitional justice, and that confronting an evil past is neither a requirement nor a pre-condition for democratization. This is primarily because the principal factors driving the impulse toward justice against the old regime are political rather than ethical or moral. In Portugal, the rise of transitional justice mirrored the anarchic politics of the revolution that lunched the transition to democracy. In Spain, the absence of transitional justice reflected the pragmatism of a democratic transition anchored on compromise and consensus. It is practically an article of faith that holding a departed authoritarian regime accountable for its political crimes through any of the available political and legal means is a pre-requisite for nations attempting to consolidate democratic rule. -

Spanish-American Relations from the Perspective of 2009

CIDOB INTERNATIONAL YEARBOOK 2009 KEYS TO FACILITATE THE MONITORING OF THE SPANISH FOREIGN POLICY AND THE INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS IN 2008 U.S.-Spain Relations from the Perspective of 2009. Adrian A. Basora Elisabets, 12 - 08001 Barcelona, España - Tel. (+34) 93 302 6495 - Fax. (+34) 93 302 6495 - [email protected] CIDOB INTERNATIONAL YEARBOOK 2009 Country profile United States of America U.S.-Spain Relations from the Perspective of 2009 Ambassador Adrian A. Basora, Senior Fellow and Director of the Project on Democratic Transitions at the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia1 The advent of the Obama Administration in Washington on January 20, 2008 was greeted with widespread enthusiasm in Spain, with many commentators on both sides of the Atlantic suggesting a new era of closer bilateral relations. Others have warned, however, that these high expectations could easily be disappointed, given the asymmetry between U.S. needs and Spanish inclinations. In this author’s judgment, there is in fact considerable potential for closer relations. This might be dismissed as the natural bias of a former American diplomat who has served with pleasure in Spain. However, the author personally experienced one of the more difficult stretches in U.S.-Spanish relations and is fully aware that harmony in the relationship is by no means pre-ordained. One has only to recall the recent dramatic low point in 2004, when Prime Minister Rodriquez Zapatero abruptly pulled all Spanish troops out of Iraq – to an extremely frigid reaction in Washington. This contrasted sharply with the euphoria of 2003, when Prime Minister Aznar joined with President Bush and Prime Minister Blair at the Azores Summit to launch the “Coalition of the Willing” and Spain dispatched 1,300 peacekeeping troops to Iraq. -

Apartheid's Contras: an Inquiry Into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique

Apartheid's Contras: An Inquiry into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp20005 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Apartheid's Contras: An Inquiry into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique Author/Creator Minter, William Publisher Zed Books Ltd, Witwatersrand University Press Date 1994-00-00 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Angola, Mozambique, South Africa, Southern Africa (region) Coverage (temporal) 1975 - 1993 Rights By kind permission of William Minter. Description This book explores the wars in Angola and Mozambique after independence. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements 31 March 2007

Annual Report and Financial Statements 31 March 2007 CONTENTS Directors and Administration……................... 2 Summary Sheet…………………….................. 3 Chairman’s Statement……………................... 4 About the Company………………................... 5 - 7 About Cuba…………………………................. 8 - 13 Investment Review…………………................. 14 - 17 Schedule of Investments………….................. 18 - 19 Directors’ Report……………………................ 20 - 22 Financial Statements………………................. 23 - 39 The opinions expressed in the sections “About Cuba” and “Investment Review” are those of the Investment Manager. The Investment Review is included in this Annual Report to provide background information to Shareholders. The information is selective and should not be used as the basis of a decision to buy or sell any particular security. Much of the information, statistics and forecasts contained in the Investment Review has been obtained or extracted from published sources and documents but no attempt has been made to verify the accuracy of such data. Information relating to Cuba may be incomplete and unreliable. Investment in Cuba may involve greater than normal risk and is not suitable for unsophisticated investors. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. 1 DIRECTORS AND ADMINISTRATION REGISTERED OFFICE Frances House, Sir William Place St Peter Port, Guernsey GY1 4HQ Tel. +44 (1481) 723573 Fax +44 (1481) 732131 REGISTRATION NUMBER 30083 INVESTMENT MANAGER ZAPA International Management Ltd. c/o CEIBA Property Corporation Ltd. -

Anti-Americanism in Spain: the Weight of History

ANTI-AMERICANISM IN SPAIN: THE WEIGHT OF HISTORY William Chislett Working Paper (WP) 47/2005 18/11/2005 Area: US-Transatlantic Dialogue – WP Nº 47/2005 18/11/2005 Anti-Americanism in Spain: The Weight of History William Chislett ∗ Summary: Spain’s feelings toward the United States are the coldest in Europe after Turkey, according to a poll by the German Marshall Fund. And they have been that way for a very long time. The country’s thermometer reading on a scale of 0-100 was 42º in 2005, only surpassed by Turkey’s 28º and compared with an average of 50º for the 10 countries surveyed (see Figure 1). The same degree of coldness towards the United States was brought out in the 16-country Pew Global Attitudes Project where only 41% of Spaniards said they had a very or somewhat favourable view of the United States. This surprises many people. After all, Spain has become a vibrant democracy and a successful market economy since the right-wing dictatorship of General Franco ended in 1975 with the death of the Generalísimo. Why are Spaniards so cool towards the United States? Spain’s feelings toward the United States are the coldest in Europe after Turkey, according to a poll by the German Marshall Fund. And they have been that way for a very long time. The country’s thermometer reading on a scale of 0-100 was 42º in 2005, only surpassed by Turkey’s 28º and compared with an average of 50º for the 10 countries surveyed (see Figure 1). -

Valósághoz (Vagy Az Esetleg Változatlan Valóságváltozó Felfo- Gásához)

BÁNHEGYI GYÖRGY A módszer tényleg halott? Szubjektív reflexiók a gondolkodás posztmodern válságára (Bevezetés) Manapság újult ervel vetdik fel a kérdés, hogy van-e jövje az európai kultúrának és civilizációnak, mködnek-e globális méretekben gondolati sémáink, a tudo- mány terén mködik-e a multikulturalizmus, vagy a mai nagy erjedésben minden, amire korábban építettünk, és számítottunk, felolvad és eltnik? Ebben a kis írásban (amelyben annak szubjektív és reflektív jellege miatt tudatosan kerültem a széleskör bibliográfia használatát, éppen csak jelzésszeren utaltam egy-két forrásra) e hatalmas témakör né- hány aspektusát szeretném felvillantani, és nem „vagy-vagy”, hanem inkább „nemcsak – hanem – is” típusú válaszokat próbálok adni rá. (Pozitivizmus, dekonstrukció, destrukció) A XX. század vége felé közhellyé vált általános válságról beszélni az európai kultúrával kapcsolatban, amelynek része a tudomány(termé - szet- és társadalomtudomány) válsága. Ehhez a XXI. század elején hozzájárul a gazdaság és a tradicionális értékek egész komplexumának válsága. Ha eszmetörténetileg zzük,né a középkor nagy szellemi szintézise1 után igen hamar repedések mutatkoztak a teológiailag megalapozott, univerzális és szintetikus világképen2, st azt mondhatjuk, hogy a(z eleinte forradalminak -szá mító, és gyanakvással szemlélt) tomista Summában és hasonló átfogó mvekbenmegjelen rendszer szinte azonnal meg is kövesedett, és éppen az lett a funkciója nem(ha is megalkotói, de felhasználói részérl) hogy sziklaszilárd alapot, bástyaszer védelmetlentsen je minden felforgató gondolattal szemben. Márpedig ami kkemény, az már nem él, nem növekszik, és nem alkalmazkodik a változó valósághoz (vagy az esetleg változatlan valóságváltozó felfo- gásához). A kés középkor dekadenciájával szemben, amelyet Huizinga3 és mások olyan ér- zékletesen mutatnak be, eleinte búvópatak-szeren jelenik meg, majd egyre erteljesebben és diadalmasabban növekszik az emberi, a racionális, a tudományos gondolat, a megfigyelhet és megérthet tényekre, és nem a (teológiai) spekulációra alapuló filozófia.