El Salvador in the 1980S: War by Other Means

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brett J. Kyle Dissertation

RECYCLING DICTATORS: EX-AUTHORITARIANS IN NEW DEMOCRACIES by Brett J. Kyle A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2013 Date of final oral examination: 08/26/13 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Christina Ewig, Associate Professor, Political Science Scott Straus, Professor, Political Science David Canon, Professor, Political Science Noam Lupu, Assistant Professor, Political Science Henry Dietz, Professor, Government © Copyright by Brett J. Kyle 2013 All Rights Reserved i To my parents, Linda Davis Kyle and J. Richard Kyle ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of my family, friends, and colleagues. In particular, I would like to thank my co-chairs, Christina Ewig and Scott Straus, for their guidance, feedback, and questions in the development and writing process; and my committee members—David Canon, Noam Lupu, and Henry Dietz—for their insights and attention to the project. I would also like to thank Leigh Payne for her direction and consistent interest in the dissertation. In addition, Andy Reiter has been a crucial guide throughout the process. The research for this project received financial support from the UW-Madison Latin American Caribbean and Iberian Studies Tinker/Nave Grant, the Vilas Travel Grant, and the Department of Political Science’s Summer Research Initiative. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, Linda Davis Kyle and Richard Kyle, and my brother, Brock Kyle, for always being there for me and for always seeing the value of my efforts. -

Our Path Forward October 7, 2015

Our Path Forward October 7, 2015 From our earliest days, The New York Times has committed itself to the idea that investing in the best journalism would ensure the loyalty of a large and discerning audience, which in turn would drive the revenue needed to support our ambitions. This virtuous circle reinforced itself for over 150 years. And at a time of unprecedented disruption in our industry, this strategy has proved to be one of the few successful models for quality journalism in the smartphone era, as well. This week we have been celebrating a remarkable achievement: The New York Times has surpassed one million digital subscribers. Our newspaper took more than a century to reach that milestone. Our website and apps raced past that number in less than five years. This accomplishment offers a powerful validation of the importance of The Times and the value of the work we produce. Not only do we enjoy unprecedented readership — a boast many publishers can make — there are more people paying for our content than at any other point in our history. The New York Times has 64 percent more subscribers than we did at the peak of print, and they can be found in nearly every country in the world. Our model — offering content and products worth paying for, despite all the free alternatives — serves us in many ways beyond just dollars. It aligns our business goals with our journalistic mission. It increases the impact of our journalism and the effectiveness of our advertising. It compels us to always put our readers at the center of everything we do. -

Schafick Jorge Handal Y La “Unidad” Del FMLN De Postguerra: Entre La Memoria Y La Historia

Diálogos v. 20 n. 2 (2016), 13-29 ISSN 2177-2940 (Online) Diálogos A2 ISSN 1415-9945 http://dx.doi.org/10.4025.dialogos.v20n2 (Impresso) Schafick Jorge Handal y la “unidad” del FMLN de postguerra: entre la memoria y la historia. El Salvador, 1992-2015 http://dx.doi.org/10.4025.dialogos.v20n2.34582 Carlos Gregorio López Bernal Docente investigador de la Licenciatura en Historia, Universidad de El Salvador. E-mail: [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________ Resumen Este artículo estudia el papel jugado por Schafick Jorge Handal en el proceso de conversión política del Frente Farabundo Martí Nacional (FMLN) en el periodo de posguerra. Se analizan los principales debates en torno a la redefinición político-ideológica del FMLN, la conducción del Palabras Clave: partido y la democracia interna. Este proceso estuvo marcado por fuertes disputas entre los FMLN; Memoria; Handal; liderazgos de las antiguas organizaciones político-militares que conformaron el FMLN. Handal Posguerra; El Salvador fue protagonista principal de estas luchas, en las que obtuvo poder y reconocimiento interno. Sin embargo, murió repentinamente en 2006, cuando el proceso de “unificación” estaba avanzado, pero no consolidado. Sin embargo, en la memoria oficial del Partido, Handal se ha convertido en el principal referente identitario del FMLN de la posguerra; no obstante que su triunfo implicó la salida del FMLN de tres de las cinco organizaciones que lo conformaron. Resumo Schafick Jorge Handal e a “unidade” do FMLN de pós-guerra: entre a memória e a história. El Salvador, 1992-2015 Este artigo examina o papel desempenhado por Schafick Jorge Handal no processo de conversão política do Frente Farabundo Martí para a Libertação Nacional (FMLN ), no período de pós- guerra. -

William Chislett

ANTI-AMERICANISM IN SPAIN: THE WEIGHT OF HISTORY William Chislett Working Paper (WP) 47/2005 18/11/2005 Area: US-Transatlantic Dialogue – WP Nº 47/2005 18/11/2005 Anti-Americanism in Spain: The Weight of History William Chislett ∗ Summary: Spain’s feelings toward the United States are the coldest in Europe after Turkey, according to a poll by the German Marshall Fund. And they have been that way for a very long time. The country’s thermometer reading on a scale of 0-100 was 42º in 2005, only surpassed by Turkey’s 28º and compared with an average of 50º for the 10 countries surveyed (see Figure 1). The same degree of coldness towards the United States was brought out in the 16-country Pew Global Attitudes Project where only 41% of Spaniards said they had a very or somewhat favourable view of the United States. This surprises many people. After all, Spain has become a vibrant democracy and a successful market economy since the right-wing dictatorship of General Franco ended in 1975 with the death of the Generalísimo. Why are Spaniards so cool towards the United States? Spain’s feelings toward the United States are the coldest in Europe after Turkey, according to a poll by the German Marshall Fund. And they have been that way for a very long time. The country’s thermometer reading on a scale of 0-100 was 42º in 2005, only surpassed by Turkey’s 28º and compared with an average of 50º for the 10 countries surveyed (see Figure 1). -

Democratic Consolidation and Capital Flight in Latin America

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: FLIGHT OR FLIGHT? DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION AND CAPITAL FLIGHT IN LATIN AMERICA Daniel Scott Owens, Doctor of Philosophy, 2017 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Virginia Haufler, Department of Government and Politics Since 1980, developing countries lost US$16.3 trillion dollars as a result of capital flight (Kar 2016) representing a major threat to international development efforts. This dissertation investigates why some democracies in the developing world experience much more capital flight than others. Using the experiences of Latin America democracies, the fundamental reasons for flight lie in the failure of these countries to consolidate their democracies. As a result of their failure to consolidate, they are highly vulnerable to popular mobilization by excluded groups demanding redistribution, which has the effect of increasing perceptions of political risk among asset holders and incurring flight. In an area of the world where wealth, income, and power is chronically unequal, my central argument posits a causal sequence that begins with mass mobilization by social movements directed towards new redistributive public policies and in opposition to pro-market democratically elected governments. Typically, as mass mobilization strengthens, Leftist parties embrace the aims of popular movements whose electoral support subsequently increases to levels that allow them to form governments committed to redistribution. Under these conditions, as mobilization and support for the Left strengthened, asset holders’ perceptions of risk increase significantly, leading to capital flight. Using a mixed methods research design combining quantitative analysis with qualitative case studies I present empirical evidence to support my argument. For the quantitative analysis, regression analysis was applied to a cross-sectional time series dataset for 18 democracies. -

Central America (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua): Patterns of Human Rights Violations

writenet is a network of researchers and writers on human rights, forced migration, ethnic and political conflict WRITENET writenet is the resource base of practical management (uk) independent analysis e-mail: [email protected] CENTRAL AMERICA (GUATEMALA, EL SALVADOR, HONDURAS, NICARAGUA): PATTERNS OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS A Writenet Report by Beatriz Manz (University of California, Berkeley) commissioned by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Status Determination and Protection Information Section (DIPS) August 2008 Caveat: Writenet papers are prepared mainly on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. The papers are not, and do not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. The views expressed in the paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Writenet or UNHCR. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ................................................................................ iii 1 Introduction........................................................................................1 1.1 Regional Historical Background ................................................................1 1.2 Regional Contemporary Background........................................................2 1.3 Contextualized Regional Gang Violence....................................................4 -

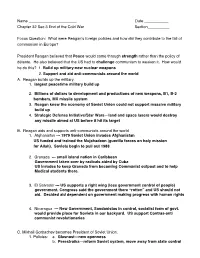

Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section___Focus Question

Name ______________________ Date ___________ Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section__________ Focus Question: What were Reaganʼs foreign policies and how did they contribute to the fall of communism in Europe? President Reagan believed that Peace would come through strength rather than the policy of détente. He also believed that the US had to challenge communism to weaken it. How would he do this? 1. Build up military-new nuclear weapons 2. Support and aid anti-communists around the world A. Reagan builds up the military. 1. largest peacetime military build up 2. Billions of dollars to development and productions of new weapons, B1, B-2 bombers, MX missile system 3. Reagan knew the economy of Soviet Union could not support massive military build up 4. Strategic Defense Initiative/Star Wars—land and space lasers would destroy any missile aimed at US before it hit its target B. Reagan aids and supports anti-communists around the world 1. Afghanistan --- 1979 Soviet Union invades Afghanistan US funded and trained the Mujahadeen (guerilla forces on holy mission for Allah). Soviets begin to pull out 1988 2. Grenada --- small island nation in Caribbean Government taken over by radicals aided by Cuba US invades to keep Granada from becoming Communist outpost and to help Medical students there. 3. El Salvador --- US supports a right wing (less government control of people) government. Congress said the government there “rotten” and US should not aid. Decided aid dependent on government making progress with human rights 4. Nicaragua --- New Government, Sandanistas in control, socialist form of govt. -

Special Warfare the Professional Bulletin of the John F

Special Warfare The Professional Bulletin of the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School PB 80–01–2 Spring 2001 Vol. 14, No. 2 From the Commandant Special Warfare United States Army special-operations forces, or ARSOF, more than any other seg- ment of the military population, recognize the importance of the human terrain in mil- itary operations. On any given day, we have approximately 800 Special Forces soldiers deployed to as many as 40 countries. Army Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations units also face a similar operations tempo. Because of the nature of ARSOF missions, our soldiers may be required to perform a variety of tasks during deployments. They may have to train host-country soldiers, communicate information to the host-coun- try population, or assist the host-country government in restoring essential services. points out in this issue, the law itself cannot Our interactions with foreign populations resolve all human-rights issues. Our soldiers have reinforced the importance of human may encounter situations that will require rights. In fact, the U.S. Special Operations them to make moral decisions, and those deci- Command has issued policy directives man- sions must reflect the soldiers’ organizational dating that SOF promote democracy and and personal values. In addition, our soldiers human rights during all overseas training must be guided not only by the moral compass and that they report any human-rights vio- provided by the Army values and by the SF val- lations committed by the foreign forces with ues, but also by the moral courage to do what is whom they are working. -

The Anti-Contra-War Campaign: Organizational Dynamics of a Decentralized Movement

International Journal of Peace Studies, Volume 13, Number 1, Spring/Summer 2008 THE ANTI-CONTRA-WAR CAMPAIGN: ORGANIZATIONAL DYNAMICS OF A DECENTRALIZED MOVEMENT Roger Peace Abstract This essay examines the nature and organizational dynamics of the anti-Contra-war campaign in the United States. Lasting from 1982 to 1990, this anti-interventionist movement sought to halt the U.S.- backed guerrilla war against the Sandinista government of Nicaragua. The forces pulling the anti- Contra-war campaign (ACWC) together and pulling it apart are analyzed. The essay is comprised of four parts: 1) overview of the Contra war and the ACWC; 2) the major activist networks involved in the ACWC, 3) the development of common political goals and educational themes; and 4) the national coordination of activities—lobbying, educational outreach, protests, and transnational activities. The final section addresses the significance of the ACWC from an historical perspective. Introduction The U.S.-directed Contra war against Sandinista Nicaragua in the 1980s sparked an anti-interventionist campaign that involved over one thousand U.S. peace and justice organizations (Central America Resource Center, 1987). The anti-Contra-war campaign (ACWC) was part of a vigorous Central America movement that included efforts to halt U.S. aid to the Salvadoran and Guatemalan governments and provide sanctuary for Central American refugees. Scholarly literature on the anti-Contra-war campaign is not extensive. Some scholars have examined the ACWC in the context of the Central America movement (Battista, 2002; Brett, 1991; Gosse, 1988, 1995, 1998; Nepstad, 1997, 2001, 2004; Smith, 1996). Some have concentrated on particular aspects of the ACWC—political influence (Arnson and Brenner, 1993), local organizing in Boston and New Bedford, Massachusetts (Hannon, 1991; Ryan, 1989, 1991), and transnational activities (Kavaloski, 1990; Nepstad, 1996; Nepstad and Smith, 1999; Scallen, 1992). -

Decision Will Come in March by JACK RONALD the Closing of That School (Pen - the Commercial Review Nville) in March,” Gulley Said

Thursday, February 2, 2017 The Commercial Review Portland, Indiana 47371 www.thecr.com 75 cents Decision will come in March By JACK RONALD the closing of that school (Pen - The Commercial Review nville) in March,” Gulley said. A decision on the status of “In order to effect a closure by Weigh in Pennville Elementary School is the fall, March would be the likely to be made in March, Jay decision point.” Jay School Corporation is gathering Schools superintendent Jere - Meeting to discuss future He stressed that as the com - opinions on methods for dealing with my Gulley said this week. its financial challenges with an online of Pennville Elementary mittee reviews a 2015 study of survey. To answer the questions and Gulley, who is working with a the school system’s buildings provide comments, visit: newly-appointed budget con - is scheduled for Tuesday and facilities the focus will not trol committee to put the be limited to Pennville. www.jayschools.k12.in.us school corporation’s fiscal “It may feel that Pennville is and click on “Cost Reduction house in order, said a special alone,” he said. “But simultane - Input and Ideas Survey.” Jay School Board meeting has ously we will look at all the facil - Prior to taking the survey, Jay been set for 6 p.m. Tuesday at Pennville Town Council, Gulley is also seeking comment ities. … It’s not just the Pen - Schools superintendent Jeremy Gulley Pennville Elementary to hear which regularly meets on the from the public via a survey on nville school that’s being consid - recommends clicking on “Jay School the concerns of parents, teach - Budget and Finance Report” in order first Tuesday of each month, the school corporation’s website ered here. -

I Command Seymour Topping; with One Mighty Hurricane Gale Gust Blast; (100) Methuselah Bright Star Audrey Topping Flaming Candles to Extinguish; …

THOSE FABULOUS TOPPING GIRLS … THE (4) SURVIVING TOPPING BRAT GIRLS & THEIR BRATTY MOM, AUDREY; ARE DISCREETLY JEWISH HALF-EMPTY; LUTHERAN HALF-FULL; 24/7/366; ALWAYS; YES; SO SMUG; SO FULL OF THEMSELVES; SUPERIOR; OH YES, SUPERIOR; SO BLUEBLOOD; (100) PERCENT; SO WALKING & TALKING; ALWAYS; SO BIRTHRIGHT COY; SO CONDESCENDING; SO ABOVE IT ALL; SO HAVING IT BOTH WAYS; ALWAYS; SO ARROGANT; THEIR TOPPING BRAT GIRL MONIKER; COULD HAVE; A MISS; IS A GOOD AS A MILE; BEEN THEIR TOPOLSKY BRAT; YET SO CLOSE; BUT NO CIGAR; THEIR TOPOLSKY BRAT GIRL WAY . OR THEIR AUGUST, RENOWNED; ON BORROWED TIME; FAMOUS FATHER; SEYMOUR TOPPING; ON HIS TWILIGHT HIGHWAY OF NO RETURN: (DECEMBER 11, 1921 - ); OR (FAR RIGHT) THEIR BLACK SHEEP ELDEST SISTER; SUSAN TOPPING; (OCTOBER 9, 1950 – OCTOBER 2, 2015). HONED RELEXIVELY INTO AN EXQUISITE ART FORM; TO STOP ALL DISSENTING DIFFERING VIEW CONVERSATIONS; BEFORE THEY BEGIN; THEIR RAFIFIED; PERFECTED; COLDER THAN DEATH; TOXIC LEFTIST FEMINIST TOPPING GIRL; SILENT TREATMENT; UP UNTIL TOPPINGGIRLS.COM; CONTROLLED ALL THINGS TOPPING GIRLS; UNTIL TOPPINGGIRLS.COM; ONE- WAY DIALOGUE. THAT CHANGED WITH TOPPINGGIRLS.C0M; NOW AVAILABLE TO GAWKERS VIA 9.5 BILLION SMARTPHONES; IN A WORLD WITH 7.5 BILLION PEOPLE; KNOWLEDGE CLASS ALL; SELF-ASSURED; TOWERS OF IVORY; BOTH ELEPHANT TUSK & WHITE POWDERY; DETERGENT SNOW; GENUINE CARD- CARRYING EASTERN ELITE; TAJ MAHAL; UNIVERSITY LEFT; IN-CROWD; ACADEMIC INTELLIGENTSIA; CONDESCENDING; SMUG; TOXIC; INTOLERANT OF SETTLED ACCEPTED THOUGHT DOCTRINE; CHAPPAQUA & SCARSDALE; YOU KNOW THE KIND; -

Nicaragua and El Salvador

UNIDIR/97/1 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Geneva Disarmament and Conflict Resolution Project Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Nicaragua and El Salvador Papers: Paulo S. Wrobel Questionnaire Analysis: Lt Col Guilherme Theophilo Gaspar de Oliverra Project funded by: the Ford Foundation, the United States Institute of Peace, the Winston Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and the governments of Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Finland, France, Germany, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, South Africa, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 1997 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. UNIDIR/97/1 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. GV.E.97.0.1 ISBN 92-9045-121-1 Table of Contents Page Previous DCR Project Publications............................... v Preface - Sverre Lodgaard ..................................... vii Acknowledgements ...........................................ix Project Introduction - Virginia Gamba ............................xi List of Acronyms........................................... xvii Maps.................................................... xviii Part I: Case Study: Nicaragua .......................... 1 I. Introduction ....................................... 3 II. National Disputes and Regional Crisis .................. 3 III. The Peace Agreement, the Evolution of the Conflicts and the UN Role.................................... 8 1. The Evolution of the Conflict in Nicaragua............ 10 2.