The Value of Insider Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Path Forward October 7, 2015

Our Path Forward October 7, 2015 From our earliest days, The New York Times has committed itself to the idea that investing in the best journalism would ensure the loyalty of a large and discerning audience, which in turn would drive the revenue needed to support our ambitions. This virtuous circle reinforced itself for over 150 years. And at a time of unprecedented disruption in our industry, this strategy has proved to be one of the few successful models for quality journalism in the smartphone era, as well. This week we have been celebrating a remarkable achievement: The New York Times has surpassed one million digital subscribers. Our newspaper took more than a century to reach that milestone. Our website and apps raced past that number in less than five years. This accomplishment offers a powerful validation of the importance of The Times and the value of the work we produce. Not only do we enjoy unprecedented readership — a boast many publishers can make — there are more people paying for our content than at any other point in our history. The New York Times has 64 percent more subscribers than we did at the peak of print, and they can be found in nearly every country in the world. Our model — offering content and products worth paying for, despite all the free alternatives — serves us in many ways beyond just dollars. It aligns our business goals with our journalistic mission. It increases the impact of our journalism and the effectiveness of our advertising. It compels us to always put our readers at the center of everything we do. -

Decision Will Come in March by JACK RONALD the Closing of That School (Pen - the Commercial Review Nville) in March,” Gulley Said

Thursday, February 2, 2017 The Commercial Review Portland, Indiana 47371 www.thecr.com 75 cents Decision will come in March By JACK RONALD the closing of that school (Pen - The Commercial Review nville) in March,” Gulley said. A decision on the status of “In order to effect a closure by Weigh in Pennville Elementary School is the fall, March would be the likely to be made in March, Jay decision point.” Jay School Corporation is gathering Schools superintendent Jere - Meeting to discuss future He stressed that as the com - opinions on methods for dealing with my Gulley said this week. its financial challenges with an online of Pennville Elementary mittee reviews a 2015 study of survey. To answer the questions and Gulley, who is working with a the school system’s buildings provide comments, visit: newly-appointed budget con - is scheduled for Tuesday and facilities the focus will not trol committee to put the be limited to Pennville. www.jayschools.k12.in.us school corporation’s fiscal “It may feel that Pennville is and click on “Cost Reduction house in order, said a special alone,” he said. “But simultane - Input and Ideas Survey.” Jay School Board meeting has ously we will look at all the facil - Prior to taking the survey, Jay been set for 6 p.m. Tuesday at Pennville Town Council, Gulley is also seeking comment ities. … It’s not just the Pen - Schools superintendent Jeremy Gulley Pennville Elementary to hear which regularly meets on the from the public via a survey on nville school that’s being consid - recommends clicking on “Jay School the concerns of parents, teach - Budget and Finance Report” in order first Tuesday of each month, the school corporation’s website ered here. -

I Command Seymour Topping; with One Mighty Hurricane Gale Gust Blast; (100) Methuselah Bright Star Audrey Topping Flaming Candles to Extinguish; …

THOSE FABULOUS TOPPING GIRLS … THE (4) SURVIVING TOPPING BRAT GIRLS & THEIR BRATTY MOM, AUDREY; ARE DISCREETLY JEWISH HALF-EMPTY; LUTHERAN HALF-FULL; 24/7/366; ALWAYS; YES; SO SMUG; SO FULL OF THEMSELVES; SUPERIOR; OH YES, SUPERIOR; SO BLUEBLOOD; (100) PERCENT; SO WALKING & TALKING; ALWAYS; SO BIRTHRIGHT COY; SO CONDESCENDING; SO ABOVE IT ALL; SO HAVING IT BOTH WAYS; ALWAYS; SO ARROGANT; THEIR TOPPING BRAT GIRL MONIKER; COULD HAVE; A MISS; IS A GOOD AS A MILE; BEEN THEIR TOPOLSKY BRAT; YET SO CLOSE; BUT NO CIGAR; THEIR TOPOLSKY BRAT GIRL WAY . OR THEIR AUGUST, RENOWNED; ON BORROWED TIME; FAMOUS FATHER; SEYMOUR TOPPING; ON HIS TWILIGHT HIGHWAY OF NO RETURN: (DECEMBER 11, 1921 - ); OR (FAR RIGHT) THEIR BLACK SHEEP ELDEST SISTER; SUSAN TOPPING; (OCTOBER 9, 1950 – OCTOBER 2, 2015). HONED RELEXIVELY INTO AN EXQUISITE ART FORM; TO STOP ALL DISSENTING DIFFERING VIEW CONVERSATIONS; BEFORE THEY BEGIN; THEIR RAFIFIED; PERFECTED; COLDER THAN DEATH; TOXIC LEFTIST FEMINIST TOPPING GIRL; SILENT TREATMENT; UP UNTIL TOPPINGGIRLS.COM; CONTROLLED ALL THINGS TOPPING GIRLS; UNTIL TOPPINGGIRLS.COM; ONE- WAY DIALOGUE. THAT CHANGED WITH TOPPINGGIRLS.C0M; NOW AVAILABLE TO GAWKERS VIA 9.5 BILLION SMARTPHONES; IN A WORLD WITH 7.5 BILLION PEOPLE; KNOWLEDGE CLASS ALL; SELF-ASSURED; TOWERS OF IVORY; BOTH ELEPHANT TUSK & WHITE POWDERY; DETERGENT SNOW; GENUINE CARD- CARRYING EASTERN ELITE; TAJ MAHAL; UNIVERSITY LEFT; IN-CROWD; ACADEMIC INTELLIGENTSIA; CONDESCENDING; SMUG; TOXIC; INTOLERANT OF SETTLED ACCEPTED THOUGHT DOCTRINE; CHAPPAQUA & SCARSDALE; YOU KNOW THE KIND; -

El Salvador in the 1980S: War by Other Means

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons CIWAG Case Studies 6-2015 El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means Donald R. Hamilton Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ciwag-case-studies Recommended Citation Hamilton, Donald R., "El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means" (2015). CIWAG Case Studies. 5. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ciwag-case-studies/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in CIWAG Case Studies by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Draft as of 121916 ARF R W ARE LA a U nd G A E R R M R I E D n o G R R E O T U N P E S C U N E IT EG ED L S OL TA R C TES NAVAL WA El Salvador in the 1980’s: War by Other Means Donald R. Hamilton United States Naval War College Newport, Rhode Island El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means Donald R. Hamilton HAMILTON: EL SALVADOR IN THE 1980s Center on Irregular Warfare & Armed Groups (CIWAG) US Naval War College, Newport, RI [email protected] This work is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. This case study is available on CIWAG’s public website located at http://www.usnwc.edu/ciwag 2 HAMILTON: EL SALVADOR IN THE 1980s Message from the Editors In 2008, the Naval War College established the Center on Irregular Warfare & Armed Groups (CIWAG). -

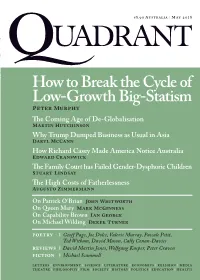

Howtobreak the Cycle of Low-Growthbig-Statism

Q ua dr a nt $8.90 Australia I M ay 2018 I V ol.62 N o.5 M ay 2018 How to Break the Cycle of Low-GrowthPeter Murphy Big-Statism The Coming Age of De-Globalisation Martin Hutchinson Why Trump Dumped Business as Usual in Asia Daryl McCann How Richard Casey Made America Notice Australia Edward Cranswick The Family Court has Failed Gender-Dysphoric Children Stuart Lindsay The High Costs of Fatherlessness Augusto Zimmermann On Patrick O’Brian John Whitworth On Queen Mary Mark McGinness On Capability Brown Ian George On Michael Wilding Derek Turner Poetry I Geoff Page, Joe Dolce, Valerie Murray, Pascale Petit, Ted Witham, David Mason, Cally Conan-Davies Reviews I David Martin Jones, Wolfgang Kasper, Peter Craven Fiction I Michael Scammell Letters I Environment I Science I Literature I Economics I Religion I Media Theatre I Philosophy I film I Society I History I Politics I Education I Health SpeCIal New SubSCrIber offer renodesign.com.aur33011 Subscribe to Quadrant and Q ua dr a nt Policy for only $104 for one year! $8.90 Australia I M arch 2012 I Vol.56 No3 M arch 2012 The Threat to Democracy Quadrant is one of Australia’ Jfromohn O’Sullivan, Global Patrick MGovernancecCauley The Fictive World of Rajendra Pachauri and is published ten times a year.s leading intellectual magazines, Tony Thomas Pax Americana and the Prospect of US Decline Keith Windschuttle Why Africa Still Has a Slave Trade Roger Sandall Policy is the only Australian quarterly magazine that explores Freedom of Expression in a World of Vanishing Boundaries Nicholas Hasluck the world of ideas and policy from a classical liberal perspective. -

9780195181234.Pdf

LOSING THE NEWS Institutions of American Democracy Kathleen Hall Jamieson and Jaroslav Pelikan, Directors Other books in the series Schooling in America: How the Public Schools Meet the Nation’s Changing Needs Patricia Albjerg Graham The Most Democratic Branch: How the Courts Serve America Jeffrey Rosen The Broken Branch: How Congress Is Failing America and How to Get It Back on Track Thomas E. Mann and Norman J. Ornstein LOSING THE NEWS The Future of the News That Feeds Democracy Alex S. Jones 1 2009 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jones, Alex S. Losing the news : the future of the news that feeds democracy / Alex S. Jones. p. cm. — (Institutions of American democracy) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

The New York Times Company 2001 Annual Report 1

596f1 2/27/02 8:21 AM Page 1 The New York Times Company SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION Shareholder Stock Listing The program assists and Globe Santa, which distributes Information Online The New York Times Company encourages promising students toys and books to needy chil- www.nytco.com Class A Common Stock is whose parents may not have dren in the greater Boston To stay up to date on the listed on the New York had the opportunity to attend area and is administered by Times Company, visit our Stock Exchange. college, to earn degrees from the Foundation, raised $1.4 Web site, where you will find Ticker symbol: NYT accredited four-year colleges million in its 2001 campaign. news about the Company as or universities. Each scholarship well as shareholder and finan- Auditors provides up to $12,000 annually Annual Meeting toward the student’s education. cial information. Deloitte & Touche LLP The Annual Meeting of Tw o World Financial Center shareholders will be held The Foundation’s 2001 annual Office of the Secretary New York, NY 10281 on Tuesday, April 16, 2002, report, scheduled for midyear at 10 a.m. (212) 556-7531 publication, is available at Automatic Dividend www.nytco/foundation or It will take place at: Corporate Reinvestment Plan by mail on request. New Amsterdam Theatre Communications The Company offers share- 214 West 42nd Street holders a plan for automatic (212) 556-4317 The New York Times Neediest New York, NY 10036 reinvestment of dividends in Cases Fund, administered by Investor Relations its Class A Common Stock the Foundation, raised $9.0 mil- for additional shares. -

Introduction

Introduction No one really thinks about it as just something to make the money. Its mission is not to make the money, it’s a quasi-public institution. The op-ed page [public discourse] is and remains the bulletin board of the world. —Gerry Marzorati, April 10, 2005 Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts. —attributed to Daniel Patrick Moynihan I. My March 1, 2011, Open Letter to the Times’s Current Publisher and Its Executive Editor Dear Arthur Sulzberger Jr. and Bill Keller: Without neglecting the continuing triumphs of what I still regard as the world’s finest newspaper, what follows is my discussion of the problems facing the New York Times and my suggestions for how to solve some of them. I have two stories to tell. The first is the story of a great newspaper reinventing itself for the twenty-first century and seeing its mission in the most idealistic terms by viewing itself as what Gerry Marzorati, the former Sunday Magazine editor, calls a “quasi-public institution.” Representing a decisive and perhaps final turn in the way newspapers operate and the American audience receives information, full commitment to digital media in the form of the paper’s website, nytimes.com, has been the centerpiece of that reinvention. But I also have a second, sadder story to tell, namely, the story of a newspaper flailing around as it tries to find its place in a world 1 © 2012 State University of New York Press, Albany 2 Endtimes? where digital news has rapidly been replacing print news, where the concepts of truth and verification are up for grabs, and where chang- ing business conditions undermine print circulation and advertising revenue, replacements for which have not been found. -

Foreclosure Filings Soar in Boroughs

TOP STORIES LIVING Restaurants crack LARGE down on diners Entrepreneur who drink too much parties on his PAGE 3 ® penthouse deck Stewart Airport Page 34 will need some heavy lifting if it’s going to fly VOL. XXIII, NO. 7 WWW.NEWYORKBUSINESS.COM FEBRUARY 12-18, 2007 PRICE: $3.00 PAGE 9 The historic pursuit READY TO ROLL of diversity coming Foreclosure together for 2008 race TVpilots hit filings soar ALAIR TOWNSEND, P. 13 Voters oppose record number Spitzer’s plans for in boroughs health care cuts Production work fills studio stages; THE INSIDER, PAGE 14 state and city tax credits a big draw Crain’s revisits Loose mortgage- top entrepreneurs; BY MIRIAM KREININ SOUCCAR lending practices largest SBA-backed come back to haunt next month, Glenn Close will star in her first television loans in NY area pilot. She plays a famous litigator who works on high-pro- homeowners SMALL BUSINESS, P. 19 file cases in New York, in a still untitled legal drama for FX. The episode, to be filmed at Steiner Studios in Brooklyn, BY TOM FREDRICKSON is one of at least 10 pilots shooting in New York City this BUSINESS LIVES spring, a record number for the city. a rapid rise in foreclosure rates “We used to be lucky to get one or two pilots,” says Alan could cost thousands of mostly MEAN low- and middle-income New STREETS Suna, president of Silvercup Studios in Long Island City, Yorkers their homes. Tough calls Queens.“Now almost every one of our stages is spoken for.” The number of homes in fore- for parents See TV PILOTS on Page 8 closure rose 18% in the last six when city months of 2006 compared with the kids go out same period of 2005, according to on their own data from RealtyTrac. -

Wallace House Journal

WALLACE HOUSE JOURNAL Fall 2018 Volume 29 | No. 1 The world’s gone mad! At least there’s Wallace House... and a royal baby! BY CATHERINE MACKIE ‘19 are still demanding a second referendum, while the Twitteratti, from both sides of the argument are still shouting a lot and putting eghan Markle is due to give birth in the Spring of 2019. their thoughts in capital letters to show HOW RIGHT THEY ARE. MHallelujah! I’m guessing I’m not alone in hoping the And if you don’t agree with me, THEN YOU’RE AN IDIOT. Queen’s eighth great-grandchild arrives in the world on March 29th. Ideally at around 11pm (GMT) because that’s the time the Which brings me to Donald Trump. No, stop it! I’m not calling the UK is scheduled to leave the European Union. If there’s one thing U.S. president an idiot. You’re taking me out of context! that’s guaranteed to give a brief respite to hours and hours of All I’m saying is that in coming to the U.S. for a year, I’ve moved hand-wringing, tediously repetitive arguments and media naval from a Brexit-obsessed media to a Trump-obsessed gazing, it’s a royal baby. media. I’m not arguing that what happens with Brexit I had hoped that coming to Ann Arbor would free me and Trump aren’t vitally important. Brexit is a key from the daily reports of EU “crisis talks” post-Brexit, moment in British modern political history. -

Strategic Report

Strategic Report Lisa Kwak Shimon Jacobs William Hetfield April 20, 2005 The New York Times Company Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................... 3 Company History .............................................................................. 4 Competitive Analysis ...................................................................... 10 Internal Rivalry......................................................................................10 Substitutes and Complements................................................................11 Buyer and Supplier Power......................................................................12 Entry ......................................................................................................13 Financial Analysis ........................................................................... 15 Key Issues...................................................................................... 19 Solutions ........................................................................................ 21 Conclusion ...................................................................................... 23 References ..................................................................................... 24 SageGroup, LLP 2 The New York Times Company Executive Summary The New York Times Company is a diversified media company that owns newspapers, television stations, radio stations, and print mills. It generates most of its revenues through its flagship -

Turner Catledge Papers MSS.116

Note: To navigate the sections of this PDF finding aid, click on the Bookmarks tab or the Bookmarks icon on the left side of the page. Mississippi State University Libraries Special Collections Department Manuscripts Division P.O. Box 5408, Mississippi State, MS 39762-5408 Phone: (662) 325–7679 E-mail: [email protected] Turner Catledge papers MSS.116 Dates: 1873-1985 Extent: circa 132 cubic feet and microfilm Preferred Citation: Turner Catledge papers, Special Collections Department, Mississippi State University Libraries. Access: Open to all researchers. Copyright Statement: Any requests for permission to publish, quote, or reproduce materials from this collection must be submitted in writing to the Manuscripts Librarian for Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of Mississippi State University as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained. Scope and Contents The collection consists of the personal and business papers of William Turner Catledge (1901-1983), graduate of Mississippi A&M College, journalist, and editor of The New York Times. Catledge was reared in Neshoba County, Mississippi, and worked for several Mississippi newspapers, the Memphis Commercial Appeal, and the Baltimore Sun before beginning his distinguished career with The New York Times in 1929. The bulk of the files date from 1945 to 1968, the period during which Catledge served as assistant managing editor, executive managing editor, managing