The United Nations' Political Aversion to the European Microstates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liechtenstein

G:\UNO\BERICHTE\Frauen\Vierter Länderbericht\4. Länderbericht-en.doc LIECHTENSTEIN Fourth PERIODIC REPORT submitted under article 18 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women of 18 December 1979 Vaduz, 11 August 2009 RA 2009/1874 2 Table of contents FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................. 3 I. OVERVIEW OF LIECHTENSTEIN........................................................................................................... 4 1. Political and social structures.................................................................................................4 2. Legal and institutional framework .........................................................................................5 II. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 8 The situation of women in Liechtenstein and implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action ...............8 III. REMARKS ON THE INDIVIDUAL ARTICLES OF THE CONVENTION ..................................................... 9 Article 2 Policy measures to eliminate discrimination against women ................................................9 Article 3 Ensuring the full development and advancement of women...............................................18 Article 4 Positive measures to accelerate de facto equality ...............................................................19 -

William Chislett

ANTI-AMERICANISM IN SPAIN: THE WEIGHT OF HISTORY William Chislett Working Paper (WP) 47/2005 18/11/2005 Area: US-Transatlantic Dialogue – WP Nº 47/2005 18/11/2005 Anti-Americanism in Spain: The Weight of History William Chislett ∗ Summary: Spain’s feelings toward the United States are the coldest in Europe after Turkey, according to a poll by the German Marshall Fund. And they have been that way for a very long time. The country’s thermometer reading on a scale of 0-100 was 42º in 2005, only surpassed by Turkey’s 28º and compared with an average of 50º for the 10 countries surveyed (see Figure 1). The same degree of coldness towards the United States was brought out in the 16-country Pew Global Attitudes Project where only 41% of Spaniards said they had a very or somewhat favourable view of the United States. This surprises many people. After all, Spain has become a vibrant democracy and a successful market economy since the right-wing dictatorship of General Franco ended in 1975 with the death of the Generalísimo. Why are Spaniards so cool towards the United States? Spain’s feelings toward the United States are the coldest in Europe after Turkey, according to a poll by the German Marshall Fund. And they have been that way for a very long time. The country’s thermometer reading on a scale of 0-100 was 42º in 2005, only surpassed by Turkey’s 28º and compared with an average of 50º for the 10 countries surveyed (see Figure 1). -

LIECHTENSTEIN the 341 © Lonely Planet Publications Planet Lonely © Malbun Triesenberg Schloss Vaduz Trail LANGUAGE: GERMAN LANGUAGE: Fürstensteig

© Lonely Planet Publications 341 Liechtenstein If Liechtenstein didn’t exist, someone would have invented it. A tiny mountain principality governed by an iron-willed monarch in the heart of 21st-century Europe, it certainly has novelty value. Only 25km long by 12km wide (at its broadest point) – just larger than Man- hattan – Liechtenstein doesn’t have an international airport, and access from Switzerland is by local bus. However, the country is a rich banking state and, we are told, the world’s largest exporter of false teeth. Liechtensteiners sing German lyrics to the tune of God Save the Queen in their national anthem and they sure hope the Lord preserves their royals. Head of state Prince Hans Adam II and his son, Crown Prince Alois, have constitutional powers unmatched in modern Europe but most locals accept this situation gladly, as their monarchs’ business nous and, perhaps also, tourist appeal, help keep this landlocked sliver of a micro-nation extremely prosperous. Most come to Liechtenstein just to say they’ve been, and tour buses disgorge day- trippers in search of souvenir passport stamps. If you’re going to make the effort to come this way, however, it’s pointless not to venture further, even briefly. With friendly locals and magnificent views, the place comes into its own away from soulless Vaduz. In fact, the more you read about Fürstentum Liechtenstein (FL) the easier it is to see it as the model for Ruritania – the mythical kingdom conjured up in fiction as diverse as The Prisoner of Zenda and Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies. -

Island Microstates: the Mirage Ofdevelopment

, , Island Microstates: The Mirage ofDevelopment John Connell There are twenty politically independent island microstates in the devel oping world-that is, states with populations of less than a million (Table I). Though various definitions of Third World microstates are possible (that might also include Mauritius, Nauru, or Singapore) none are as con venient as this crude generalization. In this paper I examine development trends in these states, reflect on the meaning of independence, and com pare and contrast the experience of these states with dependent and often neighboring territories and colonies. In particular I focus on the extent to which the structure of economic change is conducive to long-term devel opment, and seek to compare the experiences of Pacific states with those of other island microstates. These experiences are often shared by larger countries (such as Jamaica or Papua New Guinea) and by landlocked states, either in Africa (eg, Lesotho) or Asia (eg, Bhutan) or even in Europe (eg, Andorra and Liechtenstein): "it is not always easy to disentan gle the effects of smallness from those of remoteness and peripheralness or from those of newness. It may not in the end be specially profitable to try to do so" (Davies 1985, 248; cf, Connell 1988a). I shall not do so here. Islands are not so unusual, but small island states are quite different from larger states, in the structure and context of their economic development. Definitions of development have been legion, mainly revolving around issues such as basic needs, equity, self-reliance, and power. More than twenty years ago the economist Dudley Seers suggested, "The questions to ask about a country's development are: What has been happening to pov erty? What has been happening to unemployment? What has been hap pening to inequality?" (1969, 3). -

Liechtenstein Financial Market

Financial Market, Entrepreneurial Economy and Studying Finance Prof. Dr. Marco J. Menichetti Chair in Business Administration, Banking and Financial Management Institute for Finance [email protected] October 2017 Outline What is a Financial Market? Liechtenstein: Entrepreneurial Economy and Financial Market Studying Finance in Connection with an Asset Management Hub Menichetti, October 2017 2 Outline What is a Financial Market? Liechtenstein: Entrepreneurial Economy and Financial Market Studying Finance connected to an important Asset Management Hub Menichetti, October 2017 3 What is a Financial Market? Financial Financial Intermediaries/ Centers Institutions Financial Markets Regulation and Market Supervision Menichetti, October 2017 4 Financial Markets Financial Markets • Bond Markets • Stock Markets • Foreign Exchange Markets • Markets for Alternative Investments • International Financial Markets Structure of Financial Markets • Primary and Secondary Markets • Exchanges and Over-the Counter Markets • Money and Capital Markets • Spot and Forward Markets Source: Mishkin & Eakins (2016). Menichetti, October 2017 5 Financial Center Geographical location (1) that has a heavy concentration of financial institutions, (2) that offers a highly developed commercial and communications infrastructure, and (3) where a great number of domestic and international trading transactions are conducted. London, New York, and Tokyo are the world's premier financial centers. • Regional, national, international financial center • Global financial center: direct access from all over the world • Niche financial centers: Corporate Finance, Asset Management, FX, Derivatives, Trade Finance, Project Finance etc. • Onshore vs. offshore financial centers Source: Zomoré (2007); Mishkin & Eakins (2016). Menichetti, October 2017 6 Leading Wealth Management Centers (2015) - International Private Client Market Volume MARKET VOLUME (IN USD TRILLION AND AS PERCENTAGE OF MARKET SHARE) Source: Deloitte (2015). -

Towards an Understanding of the Contemporary Artist-Led Collective

The Ecology of Cultural Space: Towards an Understanding of the Contemporary Artist-led Collective John David Wright University of Leeds School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2019 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of John David Wright to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 1 Acknowledgments Thank you to my supervisors, Professor Abigail Harrison Moore and Professor Chris Taylor, for being both critical and constructive throughout. Thank you to members of Assemble and the team at The Baltic Street Playground for being incredibly welcoming, even when I asked strange questions. I would like to especially acknowledge Fran Edgerley for agreeing to help build a Yarn Community dialogue and showing me Sugarhouse Studios. A big thank you to The Cool Couple for engaging in construcutive debate on wide-ranging subject matter. A special mention for all those involved in the mapping study, you all responded promptly to my updates. Thank you to the members of the Retro Bar at the End of the Universe, you are my friends and fellow artivists! I would like to acknowledge the continued support I have received from the academic community in the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies. -

Gordon, Robert C. F

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR ROBERT C. F. GORDON Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: January 25, 1989 Copyright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background ducation arly career Baghdad 1956-1959 Baghdad Pact Organi%ation Political situation Coup Attacks on American embassy (hartoum 1959-1961 Military government Ambassador Moose Political situation Tan%ania 1964-1965 Ambassador ,illiam -eonhard Persona Non /rata President Nyerere 0ome assignment Personnel 1912-1920 Dealing with complaints Selection process ,illiam Macomber Handicapped facilities Florence 1912-1912 6.S. interests in Florence Dealing with local communist governments ye disease 1 Mauritius 1920-1928 6.S. interests in Mauritius Political situation conomic situation Conclusion Achievements Foreign Service as a career INTERVIEW Q: Mr. Ambassador, how did you become attracted to foreign affairs) /O0DO.9 ,ell, I was born and raised in a very small town in Southwest Colorado. And my father had been in the Spanish-American ,ar and had left and come back through Mexico where he stopped off and worked in the American mbassy in Mexico City for awhile on his way back to the States. And he used to talk about it. I loved travel books, and maps, and so forth. As a result, when I went to college, instead of going to the 6niversity of Colorado, I went to the 6niversity of California at Berkeley because it had a major in international relations. So I sort of had this idea in the back of my head, not knowing really what it was, since high school days. -

Anguilla: a Tourism Success Story?

Visions in Leisure and Business Volume 14 Number 4 Article 4 1996 Anguilla: A Tourism Success Story? Paul F. Wilkinson York University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/visions Recommended Citation Wilkinson, Paul F. (1996) "Anguilla: A Tourism Success Story?," Visions in Leisure and Business: Vol. 14 : No. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/visions/vol14/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Visions in Leisure and Business by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ANGUILLA: A TOURISM SUCCESS STORY? BY DR. PAUL F. WILKINSON, PROFESSOR FACULTY OF ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY 4700KEELE STREET NORTH YORK, ONTARIO CANADA MJJ 1P3 ABSTRACT More than any other Caribbean community, the Anguillans [sic )1 have Anguilla is a Caribbean island microstate the sense of home. The land has been that has undergone dramatic tourism growth, theirs immemorially; no humiliation passing through the early stages of Butler's attaches to it. There are no Great tourist cycle model to the "development" houses2 ; there arenot even ruins. (32) stage. This pattern is related to deliberate government policy and planning decisions, including a policy of not having a limit to INTRODUCTION tourism growth. The resulting economic dependence on tourism has led to positive Anguilla is a Caribbean island microstate economic benefits (e.g., high GDP per that has undergone dramatic tourism growth, capita, low unemployment, and significant passing through the early stages of Butler's localinvolvement in the industry). (3) tourist cycle model to the "development" stage. -

Cuba Tightens Foreign-Exchange Rules As Alimport Continues to Buy U.S

Vol. 13, No. 1 January 2005 www.cubanews.com In the News Cuba tightens foreign-exchange rules Adios, free zones? as Alimport continues to buy U.S. food Government says Cuba’s zonas francas do BY TRACEY EATON “Families can barely feed themselves, and not create enough jobs .................Page 3 uban President Fidel Castro summed up there is little room for luxuries like children’s 2004 like this: “There couldn’t have been toys or a night out with the family,” said James Offshore bonanza C a worse year, and there couldn’t have Cason, the top U.S. diplomat in Cuba. “Castro is been a better year, either.” determined to remain on the wrong side of his- Sherritt, Pebercan strike oil near Santa Two hurricanes, a stubborn drought, spiral- tory, while Cubans wait for his strange and Cruz del Norte ...............................Page 4 ing energy costs and stepped-up U.S. sanctions unsuccessful experiment to come to an end.” hammered the economy. But Castro supporters Undaunted, Castro celebrated his 46th year in Uruguayan friends say Cuba survived and even moved forward. power on New Year’s Day. He has outlasted nine The economy grew at a rate of 5%, and unem- American presidents and is working on his 10th. Tabaré Vázquez vows to restore full dip- ployment dropped to 2%. A reserve containing He is the longest-ruling head of government on the planet. lomatic relations with Havana ......Page 6 up to 100 million barrels of oil was discovered off the northern coast (see page 4). “He’s a tough old bird,” said a veteran foreign And in late December, Castro delivered some journalist, stunned to see the Cuban leader Caracas connection remarkable news, saying for the first time that walking in public the other day just two months Venezuela, Cuba sign sweeping free-trade the island was finally emerging from the “Spe- after he shattered his kneecap in a fall televised around the world. -

San Marino Legal E

Study on Homophobia, Transphobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Legal Report: San Marino 1 Disclaimer: This report was drafted by independent experts and is published for information purposes only. Any views or opinions expressed in the report are those of the author and do not represent or engage the Council of Europe or the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights. 1 This report is based on Dr Maria Gabriella Francioni, The legal and social situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the Republic of San Marino , University of the Republic of San Marino, Juridical Studies Department, 2010. The latter report is attached to this report. Table of Contents A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 B. FINDINGS 3 B.1. Overall legal framework 3 B.2. Freedom of Assembly, Association and Expression 10 B.3. Hate crime - hate speech 10 B.4. Family issues 13 B.5. Asylum and subsidiary protection 16 B.6. Education 17 B.7. Employment 18 B.8. Health 20 B.9. Housing and Access to goods and services 21 B.10. Media 22 B.11. Transgender issues 23 Annex 1: List of relevant national laws 27 Annex 2: Report of Dr Maria Gabriella Francioni, The legal and social situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the Republic of San Marino, University of the Republic of San Marino, Juridical Studies Department, 2010 31 A. Executive Summary 1. The Statutes "Leges Statuae Reipublicae Sancti Marini" that came into force in 1600 and the Laws that reform such Statutes represented the written source for excellence of the Sammarinese legal system. -

All Countries Visualization.Pdf

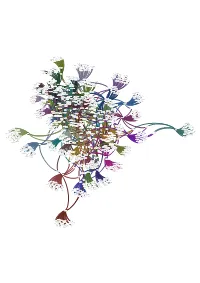

customs tariffamends principal hospitals board board control trade marks board hospital monetary authority marine board inserting next proceeds crime control over hospital insurance international sanctions government fees hospital fees merchant shipping medical practitioner legislative instruments authority application compliance authority reporting standard airworthiness directive pbssubsidised treatment radius centred thousand penalty authority procedures upon conviction column table tariff concession prudential standard column headed units imprisonment state territory specified column health research circle radius education institution copyright ministry meaning provided treatment cycle delegate chief millennium challenge liable upon statutory instrument penalty units affairs government financial supervision disciplinary committee Bermuda arising from legal person residence permit supervisory board traditional beer activity licence procedure provided approved maintenance rural municipality town council medicinal products regulatory authority requirements provided specified clause town clerk licensed premises established regulation district council close company specified employer supervision authority public sewer acts regulations insurance undertaking deleting words council resolution pouhere taonga pursuant procedure sleepovers performed information concerning eastern caribbean first reading financial markets punishable fine legal affairs exceeding months Australia statutory acknowledgement registrar general ministry legal antigua -

Volume-5, Issue-3, August-2018 ISSN No: 2349-5677

Volume-5, Issue-3, August-2018 ISSN No: 2349-5677 BUSINESS CYCLES SYNCHRONIZATION: THE CASE OF EUROPEAN MICROSTATES Dapontas Dimitrios PhD. University of Peloponnese Kalavryta, Greece [email protected] Abstract The present paper is presenting the case of five European microstates (Andorra, Lichtenstein Malta, Monaco and San Marino) respectively under the spectral analysis framework we compare the larger business cycle frequencies deployed under our knowledge (58 years 1960- 2017) to a set of four sized neighboring countries (France, Italy. Spain and Switzerland) in order to define if the microstates cycles are synchronized due to country’s size, to adjoining country or possible participation on international organizations such as European Economic Area or European monetary Union. The results show that the link to the adjacent state is stronger than the one with the same acreage or possible union counterpart due to monetary and import dependence bonds. Index Terms—Microstate, balance of payments, monetary policy, spectral analysis. I. INTRODUCTION Europe has a long history of very small countries limited to geographic or demographic limitations. The term “microstate” though is not really clear. A definition given by Dumiensky (2014) can conclude that they are “Currently established and sovereign states who gave part of their authority to stronger and grater nations, in order to protect their economic, political and social prosperity and extend them out of their limited breadth. Under this framework we can name five microstates on the European continent (Malta, Monaco, Lichtenstein, San Marino and Andorra). The present manuscript is presenting the business cycles patterns for these countries answering some important questions related to the size and the importance of these countries to the international economic system.