Tommy Cornstalk Being Some Account of the Less Notable Features of the South African War from the Point of View of the Australian Ranks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Australian War Correspondent in Ladysmith: the Siege Report of Donald Macdonald of the Melbourne Argus

http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za An Australian war correspondent in Ladysmith: The siege report of Donald Macdonald of the Melbourne Argus IAN VAN DER WAAG Military History Department, University of Stellenbosch (Military Academy) Some one hundred years ago, South Africa was torn apart by the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902). To mark this cataclysmic event, Covos-Day is publishing a series of books. The first is a facsimile of Donald Macdonald's enduring story of How we kept the flag flying through the siege of Ladysmith I and this is followed by several other titles including another Ladysmith-siege diary: one written by George Maidment, a British army orderly.2 Such a publication programme is a monumental and laudable effort. It allows both reflections upon a calamitous episode in South African history and, as is the case of How we kept the flag flying, an opportunity for the collector to acquire old titles, long-out-of-print, at reasonable prices. Donald Macdonald was born in Melbourne, Victoria on 6 June 1859. After a short career as a teacher, he joined the Corowa Free Press and, in 1881, the Melbourne Argus. A nature writer and cricket commentator,) he arrived in South Africa on 21 October 1899, the day of the battle at Elandslaagte, as war correspondent to the Melbourne Argus. This book, How we kept the flag flying, was born from his experiences and frustrations whilst holed-up in Ladysmith throughout the IDO-day siege, whilst the war raged and was reported on by journalists elsewhere. The Second Anglo-Boer War was the last truly colonial war, the last interstate conflict of the nineteenth-century, the first of the twentieth and the first media war too. -

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 by Luke Diver, M.A

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 By Luke Diver, M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Head of Department: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisors of Research: Dr David Murphy Dr Ian Speller 2014 i Table of Contents Page No. Title page i Table of contents ii Acknowledgements iv List of maps and illustrations v List of tables in main text vii Glossary viii Maps ix Personalities of the South African War xx 'A loyal Irish soldier' xxiv Cover page: Ireland and the South African War xxv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (October - December 1899) 19 Chapter 2: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (January - March 1900) 76 Chapter 3: The ‘Irish’ Imperial Yeomanry and the battle of Lindley 109 Chapter 4: The Home Front 152 Chapter 5: Commemoration 198 Conclusion 227 Appendix 1: List of Irish units 240 Appendix 2: Irish Victoria Cross winners 243 Appendix 3: Men from Irish battalions especially mentioned from General Buller for their conspicuous gallantry in the field throughout the Tugela Operations 247 ii Appendix 4: General White’s commendations of officers and men that were Irish or who were attached to Irish units who served during the period prior and during the siege of Ladysmith 248 Appendix 5: Return of casualties which occurred in Natal, 1899-1902 249 Appendix 6: Return of casualties which occurred in the Cape, Orange River, and Transvaal Colonies, 1899-1902 250 Appendix 7: List of Irish officers and officers who were attached -

The Great Boer War

The Great Boer War Arthur Conan Doyle The Great Boer War Table of Contents The Great Boer War.................................................................................................................................................1 Arthur Conan Doyle.......................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE TO THE FINAL EDITION.........................................................................................................2 CHAPTER 1. THE BOER NATIONS..........................................................................................................2 CHAPTER 2. THE CAUSE OF QUARREL...............................................................................................11 CHAPTER 3. THE NEGOTIATIONS........................................................................................................17 CHAPTER 4. THE EVE OF WAR.............................................................................................................22 CHAPTER 5. TALANA HILL....................................................................................................................30 CHAPTER 6. ELANDSLAAGTE AND RIETFONTEIN..........................................................................36 CHAPTER 7. THE BATTLE OF LADYSMITH........................................................................................40 CHAPTER 8. LORD METHUEN'S ADVANCE........................................................................................46 -

A History of Herring Lake; with an Introductory Legend, the Bride of Mystery

Library of Congress A history of Herring Lake; with an introductory legend, The bride of mystery THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 1800 Class F572 Book .B4H84 Copyright No. COPYRIGHT DEPOSIT. A HISTORY OF HEARING LAKE JOHN H. HOWARD HISTORY OF HERRING LAKE WITH INTRODUCTORY LEGEND THE BRIDE OF MYSTERY BY THE BARD OF BENZIE (John H. Howard) CPH The Christopher Publishing House Boston, U.S.A F572 B4 H84 COPYRIGHT 1929 BY THE CHRISTOPHER PUBLISHING HOUSE 29-22641 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ©C1A 12472 SEP 21 1929 DEDICATION TO MY COMPANION AND HELPMEET FOR ALMOST TWO SCORE YEARS; TO THE STURDY PIONEERS WHOSE ADVENTUROUS SPIRIT ATTRACTED THE ATTENTION OF THEIR FOLLOWERS TO HERRING LAKE AND ITS ENVIRONS; TO MY LOYAL SWIMMING PLAYMATES, YOUNG AND OLD; TO THE GOOD NEIGHBORS WHO HAVE LABORED SHOULDER TO SHOULDER WITH ME IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF OUR LOCAL RESOURCES; AND TO MY NEWER AND MOST WELCOME NEIGHBORS WHO COME TO OUR LOVELY LITTLE LAKE FOR REJUVENATION OF MIND AND BODY— TO ALL THESE THIS LITTLE VOLUME OF LEGEND AND ANNALS IS REVERENTLY AND RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED TABLE OF CONTENTS A history of Herring Lake; with an introductory legend, The bride of mystery http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.22641 Library of Congress The Bride of Mystery 9 A History of Herring Lake 19 The Fist Local Sawmill 23 “Sam” Gilbert and His Memoirs 24 “Old Averill” and His Family 26 Frankfort's First Piers 27 The Sawmill's Equipment 27 Lost in the Hills 28 Treed by Big Bruin 28 The Boat Thief Gets Tar and Feathers 28 Averill's Cool Treatment of “Jo” Oliver 30 Indian -

Thomas Paine

I THE WRITINGS OF THOMAS PAINE COLLECTED AND EDITED BY MONCURE DANIEL CONWAY AUTHOR OF L_THE LIFR OF THOMAS PAINE_ y_ _ OMITTED CHAPTERS OF HISTOIY DI_LOSED IN TH I_"LIFE AND PAPERS OF EDMUND RANDOLPH_ tt _GEORGE W_HINGTON AND MOUNT VERNON_ _P ETC. VOLUME I. I774-I779 G. P. Pumam's Sons New York and London _b¢ "lkntckcrbo¢#¢_ I_¢ee COPYRIGHT, i8g 4 BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Entered at Stationers' Hall, London BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS CONTENTS. PAGB INTRODUCTION V PREFATORY NOTE TO PAINE'S FIRST ESSAY , I I._AFRICAN SLAVERY IN AMERICA 4 II.--A DIALOGUE BETWEEN GENERAL WOLFE AND GENERAL GAGE IN A WOOD NEAR BOSTON IO III.--THE MAGAZINE IN AMERICA. I4 IV.--USEFUL AND ENTERTAINING HINTS 20 V._NEw ANECDOTES OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT 26 VI.--REFLECTIONS ON THE LIFE AND DEATH OF LORD CLIVE 29 VII._CUPID AND HYMEN 36 VIII._DUELLING 40 IX._REFLECTIONS ON TITLES 46 X._THE DREAM INTERPRETED 48 XI._REFLECTIONS ON UNHAPPY MARRIAGES _I XII._THOUGHTS ON DEFENSIVE WAR 55 XIII.--AN OCCASIONAL LETTER ON THE FEMALE SEX 59 XIV._A SERIOUS THOUGHT 65 XV._COMMON SENSE 57 XVI._EPISTLE TO QUAKERS . I2I XVII.--THE FORESTER'SLETTERS • I27 iii _v CONTENTS. PAGE XVIII.mA DIALOGUE. I6I XIX.--THE AMERICAN CRISIS . I68 XX._RETREAT ACROSS THE DELAWARE 38I XXI.--LETTER TO FRANKLIN, IN PARIS . 384 XXII.--THE AFFAIR OF SILAS DEANE 39S XXIII.--To THE PUBLm ON MR. DEANE'S A_FAIR 409 XXIV.mMEssRs. DEANS, JAY, AND G_RARD 438 INTRODUCTION. -

Tales of Clemson, 1936-1940 Arthur V

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Clemson University: TigerPrints Clemson University TigerPrints Monographs Clemson University Digital Press 2002 Tales of Clemson, 1936-1940 Arthur V. Williams, M.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/cudp_mono Recommended Citation Tales of Clemson, 1936-1940, by Arthur V. Williams, M.D. (Clemson, SC: Clemson University Digital Press, 2002), viii, 96 pp. Paper. ISBN 0-9741516-4-5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Clemson University Digital Press at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Monographs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tales of Clemson, 1936-1940 i ii Tales of Clemson 1936-1940 Arthur V. Williams, M.D. iii A full-text digital version of this book is available on the Internet, in addition to other works of the press and the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, including The South Carolina Review and The Upstart Crow:A Shakespeare Jour- nal. See our website at www.clemson.edu/caah/cedp, or call the director at 864- 656-5399 for information. Tales of Clemson 1936-1940 is made possible by a gift from Dialysis Clinics, Inc. Copyright 2002 by Clemson University Published by Clemson University Digital Press at the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, College of Architecture, Arts, and Humanities, Clemson Uni- versity, Clemson, South Carolina. Produced in the MATRF Laboratory at Clemson University using Adobe Photoshop 5.5 , Adobe Pagemaker 6.5, Microsoft Word 2000. -

1 Fighting for Empire: the Contribution and Experience of the New South

Fighting for Empire: the contribution and experience of the New South Wales Mounted Rifles first contingent in the South African War. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of BA (Hons) in History. University of Sydney. Name: Stephen Francis SID: 308161319 Date: Wednesday 5 October 2011 Word Count: 19,420 words 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my parents Peter and Jennifer and supervisor Penny Russell for taking the time to read numerous drafts of my thesis. In particular, I thank Penny for her abundant advice in regards to writing the thesis. 2 Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………..……………4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………...5 Chapter 1: The War Begins…………………………………………………….........16 Chapter 2: A Nasty Twist………………………………...……………...……..……33 Chapter 3: Welcome Home………………………………………..…………...……54 Conclusion………………………………………...……………………………..….73 Appendix………………………………………………………………………..…..76 Bibliography……………………………...……………………………………........77 3 Abstract The South African War was Australia‟s first war. Historians have insufficiently acknowledged the contribution of the New South Wales Mounted Rifles first contingent in this conflict. Unlike most Australian soldiers, the Mounted Rifles had a unique experience. Taking part in both the conventional and guerrilla phase of the war, they encountered both a familiar and unfamiliar war. After the war, they returned to a society that was largely indifferent towards them. This thesis improves our understanding of Australia‟s contribution in the South African War and reveals how the antipodes were actively involved in a wider imperial network. 4 Introduction On 9 November 1899, the Aberdeen sailed out of Sydney Harbour bound for Cape Town. Although many ships sailed between these two ports controlled by the British Empire, the nature of the Aberdeen’s voyage was unique. -

16.07.1960, Abends City High School Klamath Falls, Oregon, USA

William M. Branham Samstag, 16.07.1960, abends City High School Klamath Falls, Oregon, USA Prüft aber alles und das Gute behaltet. [1. Thessalonicher 5.21] DER WECKRUF Übersetzer: DanMer THE SHOUT www.der-weckruf.de Verantwortlich für den Inhalt dieser deutschen Übersetzung der Predigt „“ von William Branham ist: DanMer Wir vom WECKRUF greifen nicht in den Übersetzungsstil und die Wortwahl des Übersetzers ein, sondern beheben lediglich offensichtliche Rechtschreib- und Satzzeichenfehler. Sollte dir ein solcher auffallen, bitten wir höflich um Mitteilung an [email protected] Sollten Passagen dieser Übersetzung für dich unklar formuliert sein, verweisen wir zum besseren Verständnis auf https://www.der-weckruf.de/de/predigten/predigt/181018.103336.from-that-time.html Dort sind der englische Originaltext und die deutsche Übersetzung parallel angeordnet, außerdem kann dort auch die Originale Audiodatei dieser Predigt angehört werden. Wenn mehrere Übersetzungen dieser Predigt vorhanden sind, kann dort auch absatzweise von einer Übersetzung zur anderen durchgezappt werden. Originale Text-PDFs und Audiodateien stehen zum Download zur Verfügung bei https://branham.org/en/MessageAudio Die PDF dieser Übersetzung wurde erstellt am 04.10.2021 um 01:15 Uhr William M. Branham • Samstag, 16.07.1960, abends • Klamath Falls, Oregon, USA Text-Hinweise: Übersetzt wurde nur §2 und §3. Siehe dort W-1 Used to be over to another city here, something before we held it at Grants Pass. And he just, on up somewhere else in Oregon. I just met him out there, and I... You know it thrills you to meet old friends again, it does me. And I think of him all the time. -

Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony

he collection of essays presented in “Devotional Cross-Roads: Practicing Love of God in Medieval Gaul, Jerusalem, and Saxony” investigates test case witnesses of TChristian devotion and patronage from Late Antiquity to the Late Middle Ages, set in and between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, as well as Gaul and the regions north of the Alps. Devotional practice and love of God refer to people – mostly from the lay and religious elite –, ideas, copies of texts, images, and material objects, such as relics and reliquaries. The wide geographic borders and time span are used here to illustrate a broad picture composed around questions of worship, identity, reli- gious affiliation and gender. Among the diversity of cases, the studies presented in this volume exemplify recurring themes, which occupied the Christian believer, such as the veneration of the Cross, translation of architecture, pilgrimage and patronage, emergence of iconography and devotional patterns. These essays are representing the research results of the project “Practicing Love of God: Comparing Women’s and Men’s Practice in Medieval Saxony” guided by the art historian Galit Noga-Banai, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the histori- an Hedwig Röckelein, Georg-August-University Göttingen. This project was running from 2013 to 2018 within the Niedersachsen-Israeli Program and financed by the State of Lower Saxony. Devotional Cross-Roads Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony Edited by Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover Röckelein/Noga-Banai/Pinchover Devotional Cross-Roads ISBN 978-3-86395-372-0 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover (Eds.) Devotional Cross-Roads This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

De Charlotte Perriand

Master en Teoria y Práctica del Proyecto Arquitectónico Análisis de los refúgios de montañismo y “cabañas de weekend” de Charlotte Perriand Estudiante: GEORGIA NTELMEKOURA Profesores: Josep Quetglas, Victor Brosa ETSAB – MAYO 2008 Master on Theory and Practice of Architectural Design Analysis of the mountain shelters and weekend huts by Charlotte Perriand Student: GEORGIA NTELMEKOURA Profesors: Josep Quetglas, Victor Brosa ETSAB – MAY 2008 3 “May we never loose from our sight the image of the little hut” -Marc-Antoine Laugier, “Essai sur l’Architecture”- Index 1. Preface 5 1.1 Prior mountain shelters in Europe 6 2. Presentation-Primary analysis 2.1 Weekend hut –Maison au bord de l’ eau(Competition) 11 2.2 “Le Tritrianon shelter” 16 2.3 “Cable shelter” 23 2.4 “Bivouac shelter” 27 2.5 “Tonneu barrel shelter” 31 2.6 “shelter of double construction” 34 3. The minimun dwelling 38 4. Secondary interpretation 47 4.1The openings 47 4.2 The indoor comfort conditions 48 4.3 Skeleton and parts 50 4.4 The materials 52 4.5 The furniture 53 4.6 The bed 57 5. Conclusions 59 6. Bibliography 61 7. Image references 62 4 1.Preface This essay was conceived in conversation with my professors. Having studied already the typology of my country’s mountain shelters and a part of the ones that exist in Europe, I welcomed wholeheartedly the idea of studying, in depth, the case of Charlotte Perriand. As my investigation kept going on the more I was left surprised to discover the love through which this woman had produced these specific examples of architecture in nature. -

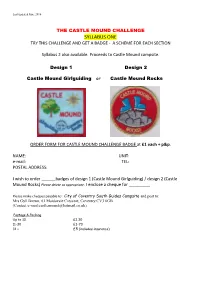

Syllabus One Try This Challenge and Get a Badge - a Scheme for Each Section

Last updated June 2016 THE CASTLE MOUND CHALLENGE SYLLABUS ONE TRY THIS CHALLENGE AND GET A BADGE - A SCHEME FOR EACH SECTION Syllabus 2 also available. Proceeds to Castle Mound campsite. Design 1 Design 2 Castle Mound Girlguiding or Castle Mound Rocks ORDER FORM FOR CASTLE MOUND CHALLENGE BADGE at £1 each + p&p. NAME: UNIT: e-mail: TEL: POSTAL ADDRESS: I wish to order ______badges of design 1 (Castle Mound Girlguiding) / design 2 (Castle Mound Rocks) Please delete as appropriate. I enclose a cheque for _________ Please make cheques payable to: City of Coventry South Guides Campsite and post to: Mrs Gyll Brown, 61 Maidavale Crescent, Coventry.CV3 6GB (Contact e-mail:[email protected]) Postage & Packing Up to 10 £1.30 11-30 £1-70 31 + £5 (includes insurance) Last updated June 2016 Syllabus One RANGERS/EXPLORERS Choose ONE challenge from section ONE or Choose 2 challenges from section TWO SECTION 1 Choose ONE of the following: (You will need a suitably qualified leader to check your planning and accompany you. Rules of the Guiding Manual must be followed). 1. Help plan and take part in a backpacking hike with a stopover in lightweight tents. Carry your tent and cooking equipment with you. You need to plan well and share the weight). 2. Help organise and participate in an overnight camp. Help to plan menus (including quantities) and a programme. 3. Build a bivouac (shelter) and sleep in it. Cook one meal without using utensils (except a knife) SECTION 2 Choose 2 of the following: 1. Plan and organise an outdoor Wide Game for a younger section. -

Sir Abe Bailey

• I ·SIR ABE BAILEY His Life and Achie~e~ . ' li I I l History Honours Research Paper I I by I ,. Hamilton Sayer University of Cape )own, 19740 . < African Studies (94 0108 3200 ·1~l I! ll Ill IIll !II I! ~ /l 11 ;···. I' . I The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. CONTENTS PREFACE . .. i BAILEY'S EARLY YEARS . .. .. .. 1 THE RAND AND RHODES . .. .. .. 6 BAILEY AND THE JAMESON RAID ..•.•.•..•.•.••...•..• 14 THE SECOND SOUTH AFRICAN WAR ..•.•..•.•.•....•.... 21 BAILEY IN THE CAPE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY .••.•....• 25 FIVE.YEARS OF TRANSVAAL POLITICS ...•.....••...... 32 THE CLOSER UNION MOVEMENT •..•.•.....•••.. ., . • . 45 BAILEY IN THE UNION PARLIAMENT: 1915 - . 1924 ....•. 49 RECONCILIATION, NATIONAL UNITY AND THE ~MPIRE 59 THE LAST TEN YEARS • . • . • . • . • . 65 BAILEYi S LEGACY . • . • • . • • . • . • . • . • . • . • 69 CONCLUSION . • • • . • . • • • • • . • • • • • . • • • •.. • • • • • • • • . • • • . 7 4 i PREFACE On the suggestion that something be written on Abe Bai~ ley, the first question to pass through my mind was, who on earth is Abe Bailey anyway? The name sounded reasonably familiar. And indeed i~ is. For most people, the name 'Bailey' is associated with the Abe Bailey Institute of Inter-Racial .Studies (now called. 'Centre for Inter-Group Studies') and the Abe Bailey Bursary, the latter· being a grant to_ help university students finance their studies. But,· it is probably true to say that not much more is known ·:about this ma~, wh~ in ~is own way, contributed so much to Souih Afiica in such.a variety of fields.