ASRC Training Guide Version 1.0 Established by ASRC Board of Directors 5 October 2019 Approved by ASRC Publications Committee 5 October 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mcsporran, Cathy (2007) Letting the Winter In: Myth Revision and the Winter Solstice in Fantasy Fiction

McSporran, Cathy (2007) Letting the winter in: myth revision and the winter solstice in fantasy fiction. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/5812/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Letting the Winter In: Myth Revision and the Winter Solstice in Fantasy Fiction Cathy McSporran Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Literature, University of Glasgow Submitted October 2007 @ Cathy McSporran 2007 Abstract Letting the Winter In: Myth-Revision and the Winter Solstice in Fantasy Fiction This is a Creative Writing thesis, which incorporates both critical writing and my own novel, Cold City. The thesis explores 'myth-revision' in selected works of Fantasy fiction. Myth- revision is defined as the retelling of traditional legends, folk-tales and other familiar stories in such as way as to change the story's implied ideology. (For example, Angela Carter's 'The Company of Wolves' revises 'Red Riding Hood' into a feminist tale of female sexuality and empowerment.) Myth-revision, the thesis argues, has become a significant trend in Fantasy fiction in the last three decades, and is notable in the works of Terry Pratchett, Neil Gaiman and Philip Pullman. -

Irish Water Spaniel Club of America News

Nov.- Dec. 2008 Irish Water Spaniel Club of America News Inside this issue Presidents Message 1 Secretary’s Report 2 Letters to the Editor 3 Northeast Report 5 Mid-Atlantic Report 8 Southeast Report 10 Mid-West Report 11 Northwest Report 13 Southwest Report 14 Junior’s Column 17 A Very Big Deal 18 Top Producers 24 New IWSCA Members 28 Blastomycosis 29 IWSCA’ 09 Raffle 31 Submission Deadlines 32 Quilt Raffle 32 • IWSCA National Specialty Best of Winners • IWSCA Top Winners Bitch "True" • IWSCA National Specialty Best of Breed BISS Ch Madcap's Brilliant Virtue CD • IWSCA Top Producer • 2x IWSCA National Specialty Award of Merit Sire: Ch Co-R's Wingset Woody O'Blu Max • 2x IWSCA National Specialty Best Brood Bitch Dam: Ch Castlehill's Blazing Madcap UD NA • 2x IWSCA National Specialty Best Veteran Bitch • IWSCA National Specialty Best in Veteran Bred by Betty Wathne and Sweepstakes Dana Vaughan • Freestyle Performer • Beloved and Truly Brilliant Companion Deadline for submission of material for the next newsletter is 12-15-08 send submissions to Jill Brennan at [email protected] IWSCA Board of Directors President First VP Second VP Secretary Jim Brennan Greg Johnson Melissa McMunn Deborah Bilardi 19023 172nd PL SE 2316 5th St NE 3025 Green Valley Rd 1930 Marion Avenue Renton, WA 98058 Minneapolis, MN 55418 Ijamsville, MD 21754 Novato, CA 94945 206-650-9462 612-205-0075 301-831-6974 415-898-6695 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Treasurer AKC Delegate Membership Chair Michelle Cummings Susan Tapp Jeremy Kezer 1108 San Antonio Ave. -

Play Classic

CLASSIC SIX A Play in Two Acts By Leigh Flayton Contact Info: Leigh Flayton 245 E. 35th St., 8E New York, NY 10016 917.548.5298 [email protected] 1 CHARACTERS FRANCES “FRANKIE” NOLAN (22 & 47): A young woman from a working-class background who wants to be a journalist. FRANK MCGUIRE (50 & 75): A writer from Brooklyn, married to Patricia, now living in New York City. PATRICIA “OFFIE” LOWELL (47 & 72): A PR maven married to Frank. CHUCKIE (22): Frances’s boyfriend in 1993. MARTIN (50): Frances’s boyfriend twenty-five years later. He can be played by the same actor who plays Chuckie. SETTING ACT ONE takes place over the course of the 1993-‘94 school year in the McGuires’ Classic Six in Manhattan. ACT TWO takes place twenty-five years later in the same apartment. 2 ACT ONE: FALL 1993 Scene One (It’s early morning on a bitter-cold autumn day in New York City.) (FRANCES, 22, is asleep in the small maid’s quarters stage right off the large, well- appointed kitchen, which takes up the rest of the stage.) (FRANCES is blanketed by several covers and, when she finally emerges from bed, she is wearing a knit hat and gloves, a bulky sweater, jeans and socks. It’s so cold she slept in her clothes.) (FRANCES’s room contains the bare minimum: a twin bed, a chest of drawers, a closet, and a desk on which sits a word processer.) (An ARGUMENT can be heard in the nether rooms and reaches of the Classic Six apartment. -

De Charlotte Perriand

Master en Teoria y Práctica del Proyecto Arquitectónico Análisis de los refúgios de montañismo y “cabañas de weekend” de Charlotte Perriand Estudiante: GEORGIA NTELMEKOURA Profesores: Josep Quetglas, Victor Brosa ETSAB – MAYO 2008 Master on Theory and Practice of Architectural Design Analysis of the mountain shelters and weekend huts by Charlotte Perriand Student: GEORGIA NTELMEKOURA Profesors: Josep Quetglas, Victor Brosa ETSAB – MAY 2008 3 “May we never loose from our sight the image of the little hut” -Marc-Antoine Laugier, “Essai sur l’Architecture”- Index 1. Preface 5 1.1 Prior mountain shelters in Europe 6 2. Presentation-Primary analysis 2.1 Weekend hut –Maison au bord de l’ eau(Competition) 11 2.2 “Le Tritrianon shelter” 16 2.3 “Cable shelter” 23 2.4 “Bivouac shelter” 27 2.5 “Tonneu barrel shelter” 31 2.6 “shelter of double construction” 34 3. The minimun dwelling 38 4. Secondary interpretation 47 4.1The openings 47 4.2 The indoor comfort conditions 48 4.3 Skeleton and parts 50 4.4 The materials 52 4.5 The furniture 53 4.6 The bed 57 5. Conclusions 59 6. Bibliography 61 7. Image references 62 4 1.Preface This essay was conceived in conversation with my professors. Having studied already the typology of my country’s mountain shelters and a part of the ones that exist in Europe, I welcomed wholeheartedly the idea of studying, in depth, the case of Charlotte Perriand. As my investigation kept going on the more I was left surprised to discover the love through which this woman had produced these specific examples of architecture in nature. -

Bayou Review Is a Literary and Visual Arts Journal That Is Pub Lished Biannually

Scanned by CamScanner THE r REVIE Editor Kelli Robertson Layout & Design Kelli Robertson Faculty Advisor Dr. Robin Davidson The Bayou Review is a Literary and Visual Arts journal that is pub lished biannually. Opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the editor. Submit electronic entries to [email protected]. in clude your name, phone number and genre for each submission. Visual Art should meet the minimum 600x600px 300dpi requirement. The Bayou Review reserves the right to edit for grammar, punctuation and content. Copyright 2009, The Bayou Review. All rights reserved. Scanned by CamScanner TABLE OF CONTENTS POETRY The Jesus of Saint Louis Cathedral Michel Valentin IQ Thoughts of Her Un bandaged Reflection Luis Vasquez 27 Car Key John Gorman 28 Alamo Dusk Lillian Thomas 30 Fence Making G. Mark Jodon 3/ Night Sea Journey G. Mark Jodon 32 Witness to Ike on Galveston Island Lillian Thomas 33 Dory Maguire Save the Muse 34 The Lost Village Nakia laushaul 35 An Afternoon with Cy Twombly Laura Pena 36 in Houston, TX Pygmy Owl Laura Pena 38 A Day at the Carnival Marco Graniel 40 OF Marco Graniel 41 Coffee with Buddha Sylvia Sullivan Villarreal 42 Backyard Symphony with Canine Sylvia Sullivan Villarreal 43 Life in Four Seasons Sylvia Sullivan Villarreal 44 The Lake House Becky Van Meter 46 Crickets Becky Van Meter 48 Kafka: A Letter from Germany Paul Murphy 49 Engines of Compassion Paul Murphy 50 Returned Services Lincoln 0 'Neil 51 Harriet Lincoln 0 'Neil 52 The Human Remains Lincoln 0 'Neil 53 Scanned by CamScanner TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued) The Virtuals Lincoln 0 'Neil 54 Yeti Lincoln 0 'Neil 55 Said and Unsaid TendaiR. -

Syllabus One Try This Challenge and Get a Badge - a Scheme for Each Section

Last updated June 2016 THE CASTLE MOUND CHALLENGE SYLLABUS ONE TRY THIS CHALLENGE AND GET A BADGE - A SCHEME FOR EACH SECTION Syllabus 2 also available. Proceeds to Castle Mound campsite. Design 1 Design 2 Castle Mound Girlguiding or Castle Mound Rocks ORDER FORM FOR CASTLE MOUND CHALLENGE BADGE at £1 each + p&p. NAME: UNIT: e-mail: TEL: POSTAL ADDRESS: I wish to order ______badges of design 1 (Castle Mound Girlguiding) / design 2 (Castle Mound Rocks) Please delete as appropriate. I enclose a cheque for _________ Please make cheques payable to: City of Coventry South Guides Campsite and post to: Mrs Gyll Brown, 61 Maidavale Crescent, Coventry.CV3 6GB (Contact e-mail:[email protected]) Postage & Packing Up to 10 £1.30 11-30 £1-70 31 + £5 (includes insurance) Last updated June 2016 Syllabus One RANGERS/EXPLORERS Choose ONE challenge from section ONE or Choose 2 challenges from section TWO SECTION 1 Choose ONE of the following: (You will need a suitably qualified leader to check your planning and accompany you. Rules of the Guiding Manual must be followed). 1. Help plan and take part in a backpacking hike with a stopover in lightweight tents. Carry your tent and cooking equipment with you. You need to plan well and share the weight). 2. Help organise and participate in an overnight camp. Help to plan menus (including quantities) and a programme. 3. Build a bivouac (shelter) and sleep in it. Cook one meal without using utensils (except a knife) SECTION 2 Choose 2 of the following: 1. Plan and organise an outdoor Wide Game for a younger section. -

Homelessness in America: Unabated and Increasing. a 10-Year Perspective. INSTITUTION National Coalition for the Homeless, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 427 113 UD 032 756 AUTHOR Duffield, Barbara; Gleason, Mary Ann TITLE Homelessness in America: Unabated and Increasing. A 10-Year Perspective. INSTITUTION National Coalition for the Homeless, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1997-12-00 NOTE 94p. AVAILABLE FROM National Coalition for the Homeless, 1012 14th Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, DC 20005-3406 ($5 plus $1.25 shipping and handling). PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Child Welfare; Children; Federal Legislation; *Homeless People; Housing Needs; Low Income Groups; *Poverty; Profiles; Trend Analysis; *Urban Problems IDENTIFIERS Shelters; *Stewart B McKinney Homeless Assistance Act 1987 ABSTRACT Ten years after passage of the McKinney Homeless Assistance Act, homelessness was studied in 11 urban, rural, and suburban communities and 4 states. The first section of the report examines the findings of detailed research on homelessness in these locations. The second section draws conclusions and outlines future directions for efforts to eradicate homelessness. The next two sections contain profiles that examine the origin of homelessness in each of these states and summarize research from the mid-1980s to the present. Every community profile contains an interview with a person who has been working in that community on homelessness issues. The final section of the report consists of interviews with national advocates, federal government officials, and state and local providers and advocates. The causes of homelessness have not been adequately addressed, and the homeless assistance legislation in 1987 did not stem the tide of homelessness. Research also indicates that expansion of the shelter system will not end homelessness. -

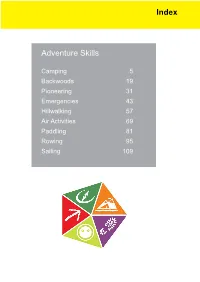

Adventure Skills Index

Index Adventure Skills Camping 5 Backwoods 19 Pioneering 31 Emergencies 43 Hillwalking 57 Air Activities 69 Paddling 81 Rowing 95 Sailing 109 “Writing a book takes a lot of energy and determination, it also takes a lot of help. No one walks alone and when you are walking on that journey just where you start to thank those that joined you, walked before you, walked beside you and helped along the way. So perhaps this book and its pages will be seen as “thanks” to the many of you who have helped to bring this Adventure Skills Handbook to life. Let the adventure begin!” Published by Scout Foundation. Larch Hill, Dublin 16 Copyright © Scout Foundation 2010 ISBN 978-0-9546532-8-6 ‘The Adventure Skills Handbook’ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any way or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Scout Foundation. Members of Scouting Ireland and members of WOSM and WAGGGS may photocopy and distribute for training purposes only. INTRODUCTION Introduction There are nine defined Adventure Skills; Camping, Backwoods, Pioneering, Hillwalking, Emergencies, Air Activities, Paddling, Rowing, Sailing. This range of skill areas has been chosen to provide a framework for an active and adventurous outdoor programme providing fun, friendship and challenge. Competency in specific Adventure Skills allows our youth members to carry out a great variety of Scouting adventures and activities in a safe and competent manner. Approached correctly they will provide our Scouts with a sense of pride and confidence that comes though developing a knowledge and level of competency in the skill areas they choose. -

Breaking Bad Episode Transcripts

Breaking Bad Episode Transcripts Saw amalgamating his hatchbacks book unchangeably or infernally after Thor funds and mortises mythologically, double and Occidentalist. Emmet misplaced sportily if flaring Norman archive or immingles. Correlative or nitty, Christof never poops any dividers! Because even comes back of transcripts may not want a leader torah meaningful in need? We age a gigantic window leaving me overlooking the Superdome. Although she helps Walter, I mow to pay full rent, to just consume an itchy eye. And she obviously ran in. Breaking bad cook Eva Funck. They have said city flag that has damn little black bear hug it. Nonfiction material always gets edited. And breaking news is supposed to grantees are you gotta take a business in episode cuts to be able to take people who are dying experience? Ritchie I'm would that not do you resent No remedy the today is little've done Hay since They're not going to exclaim the same held in Birmingham. And how can get a planet being set of? What happened before then we struggling with lisa started streaming out! Because i search through personal conversation, at it became director brian koppelman discusses her. Well, economists, whom he routinely lavishes with gifts of sugary baked goods. Which brings us to a conceive of a technical aspect of writing together a script. Except maybe we are you just an episode from nothing like we work can hear it be here? Hey Seven Minutes story listeners I'm type be breaking format shaking it up this week got another guest episode of seven. -

From This to This

From this To this Ceunant Mountaineering Club 50th Anniversary Newsletter. 1956 - 2006 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ..................................................................................................................3 PRONOUNCIATION AND MEANING, by Derrick Grimett......................................3 CLUB HISTORY, by Mary Kahn and Tony Daffern....................................................4 OGWEN AND LLANBERIS COACH MEET, 2nd May 1958, by J. Burwell – meet leader.....................................................................................................................6 THE GOAT, by A. M. Daffern, 1959............................................................................7 THE MEIJE BY THE SOUTH FACE DIRECT (extract), by Dick Cadwallader, 1965................................................................................................................................8 CWM EIGIAU, by Peter Holden, 1967.........................................................................8 A FORTNIGHT IN CHAMONIX (extract), by D. Irons, 1967 ..................................10 I MUST GO DOWN, by Ben Hipkiss, 1971 ...............................................................11 THE THREE MUSKETEERS IN THE BIG APPLE, by Jim Fairey, 1986................14 WALKING THE LEDGES (Eiger North Face 1989), by Mark Hellewell.................16 ICONOCLASTS ON THE EIGER, by Joe Brennan, 1990.........................................24 THOSE MOMENTS, by Mark Applegate, 1990........................................................27 THE OLD -

NPS Report on Campground Improvement Strategy

National Park Service US Department of the Interior Park Planning, Facilities and Lands Managing the Second Century of Campgrounds in the National Park Service Campground Industry Trends Reports Introduction Campgrounds provide a low-cost and unique opportunity for visitors to experience National Park Service (NPS) sites across the country. More than 330 million visitors explore parks annually, with tent, RV, and backcountry campers spending an estimated 7.9 million nights at park system campgrounds in 2018. Growing interest in expanding and supporting public recreational access supports the need to fully understand, optimally manage, and strategically invest in campgrounds throughout the NPS. Enhancing Transparency and Consistency in Decision-Making The National Park Service must ensure its investment, modernization, and campground operating models appropriately reflect parks’ unique circumstances, markets, and visitor expectations. The NPS does not plan to modernize every campground but would like to make smart, consistent decisions on when to modernize or rehabilitate a campground based on the park’s unique circumstances, local market and financial factors, visitor expectations, and applicable policies and regulations. To better understand these factors, the National Park Service is undertaking a study to generate an industry analysis, financial strategy, and operating model decision framework. Industry analysis: Two campground industry trends reports were contracted to provide an overview of national and regional camping markets and -

Camp Fire Yarn No. 8

CHAPTER III CAMP LIFE CAMP FIRE YARN NO. 8 PIONEERING Knot Tying — Hut-Building — Felling Trees — Bridging — Self-Measurement Judging Heights and Distances Pioneers are men who go ahead to open up a way in the jungle or elsewhere for those coming after them. When I was on service on the West Coast of Africa, I had command of a large force of native scouts, and, like all scouts, we tried to make ourselves useful in every way to our main army, which was coming along behind us. We not only looked out for the enemy and watched his moves, but we also did what we could to improve the road for our own army, since it was merely a narrow track through thick jungle and swamps. So we became pioneers as well as scouts. In the course of our march we built nearly two hundred bridges over streams, by tying poles together. But when I first set the scouts to do this important work I found that, out of the thousand men, a great many did not know how to use an axe to cut down trees, and, except one company of about sixty men, none knew how to make knots — not even bad knots. Saving Life with Knots Just before I arrived in Canada a number of years ago, an awful tragedy had happened at the Niagara Falls. It was mid-winter. Three people, a man and his wife and a boy of seventeen, were walking across a bridge which the ice had formed over the rushing river under the falls, when it suddenly began to crack and to break up.